Bank Notes

advertisement

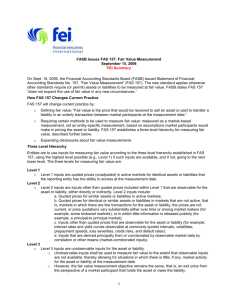

Bank Notes January/February 2008 A timely information and idea statement FASB accounting standard could create surprises for community banks The Financial Accounting Standards Board issued its Fair Value Measurements Statement No. 157 (FAS 157) in the fall of 2006. The objectives of FAS 157 include creating a single definition of fair value, establishing a framework for fair value and expanding disclosures about fair value measurements. This results in raising the bar for measuring fair values currently required by generally accepted accounting principles. With a few exceptions, including share-based payment transactions, FAS 157 applies to fair value measurements already permitted or required under other accounting pronouncements where the FASB has concluded that fair value is the relevant measurement attribute. FAS 157 doesn’t expand the use of fair value measurements by community banks for balance sheet items. In addition, there may be some confusion over fair value accounting due to the issuance of FASB Statement No. 159 (FAS 159) in early 2007. The Fair Value Option for Financial Assets and Financial Liabilities includes the opportunity to mitigate income statement volatility without applying hedge accounting rules and expanding the use of fair value. Though applicability of FAS 159 is an option, it isn’t for FAS 157. However, both FAS 157 and FAS 159 are effective for years beginning after Nov. 15, 2007, which may add to the confusion. FAS 157 defines fair value as the price that would be received to sell an asset or paid to transfer a liability in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date. This definition means that the “exit” price versus the “entry” price is a better measurement of fair value. The primary focus of FAS 157 is the description of the hierarchy for determining fair value. This ranking explains the inputs into valuation techniques for measurement of fair values using the following data: Level 1 –Quoted prices (unadjusted) in active markets for identical assets or liabilities Level 2–Inputs other than quoted market prices included in level 1 that are observable for the asset or liability, either directly or indirectly Level 3–Unobservable inputs Examples of how these inputs might be employed by a community bank for its financial reporting could be: Level 1 –U.S. Treasury securities Level 2–Restricted investments Level 3–Mortgage servicing rights, municipal securities or goodwill Other areas that need considering include loans, loans held for sale, impaired loans, other real estate owned, goodwill and core deposits. FAS 157 indicates that valuation techniques utilized to measure fair value shall maximize the use of observable inputs and minimize the use of unobservable inputs. Disclosure requirements about the use of fair value used to measure assets and liabilities focus on the inputs used to measure fair value. For reoccurring fair value measurements using significant unobservable (level 3) inputs, the focus is the effect of the measurements on earnings for the period. To meet this objective, the bank will need to disclose the following information for each major category of asset or liability: • The fair value measurements at the reporting date • The level within the fair value hierarchy in which the fair value measurements fall, segregating fair value measurements into level 1, level 2 or level 3 • The reconciliation of beginning and ending balances — for assets or liabilities using level 3 unobservable inputs • The gain or loss recognized in earnings that are attributable to the change in unrealized gains or losses • The valuation techniques used to measure fair value and a discussion of changes in valuation techniques, if any, during the period What does this mean to community banks? Since FAS 157 will apply to the financial statements issued in 2008, FASB accounting standard, continued on page 3 Be a fearless — not a fearful — leader “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” This famous quote from Franklin Roosevelt speaks as clearly to leaders today as it did in the 1940s. In their book, Play to Win, Larry and Hersch Wilson present psychologist Maxie Maultsby’s concept of the Four Fatal Fears. Maultsby believes these fears impede our ability to interact effectively with others and take relevant action. Consider how the following four fears possibly affect your ability to lead your bank. 1. I fear failure; therefore, I need to succeed When leaders operate from a fear of failure, they are often reluctant to act. They may procrastinate in making decisions and miss opportunities. A fear of failure can manifest itself as a need to have every piece of available information before making a decision. Leaders who fear failure can become imaginatively stuck and in the constant mode of finding answers, rather than reframing questions. 2. I fear being wrong; therefore, I must be right For leaders, the fear of being wrong can make it extremely difficult to tolerate members of their management team who challenge their ideas or conclusions. Ultimately, leaders’ fear of being wrong leads to an increased likelihood that they will be wrong. Leaders who need to be right tend to dominate discussions and attempt to control the thinking of others, rather than see others as resources who can expand their understanding of issues and opportunities. 3. I fear rejection; therefore, I need to be accepted Fear of rejection makes it difficult for leaders to take a stand and define themselves in situations where relationships feel endangered. These leaders tend to rely exclusively on a consensus decision-making style because they believe it’s more important to be liked than respected. More introverted leaders deal with the fear of rejection by pulling away from relationships and cutting themselves off from the very people with whom they desire connection. 2 BankNotes 4. I fear being emotionally uncomfortable; therefore, I need to be comfortable When leaders need emotional comfort, they lack the capacity to remain present and engaged when faced with resistance or anger from others. They tend to avoid emotionally charged discussions and miss the opportunity for mutual learning and growth. When leaders act out of fear, their actions and decisions are guarded and restrictive. Their fears and anxieties are transmitted to their organizations, which creates dependency, indecisiveness and lack of personal responsibility. These shared fears can replace the firm’s shared values and lead to ethical lapses, poor and untimely decisions, ineffective communication and dysfunctional relationships. To help determine how fear impacts your leadership, ask yourself – for the next week, twice daily (midday and day’s end) – the following questions: [I fear failure; therefore, I must succeed] • What didn’t I attempt today because I was afraid I would fail? • How did I rationalize not trying? • What was the worst outcome that could have come out of my trying? • What didn’t move forward because I didn’t try? [I fear being wrong; therefore, I need to be right] • In what situation did I feel the need to be right or to avoid being wrong? • How did I respond? • How did other people respond to me? • How could I have responded that would have been more useful? [I fear rejection; therefore, I need to be accepted] • In what situation did I feel rejected today? • How did I respond? • How could I have responded more effectively to stay connected? • What situation did I avoid today because I was afraid of rejection? • What was the result of my avoidance? • How could I have engaged that person? [I fear being emotionally uncomfortable; therefore, I need to be comfortable] • What made me emotionally uncomfortable today? • Why was I uncomfortable? • What did I do to avoid or eliminate the discomfort? • What didn’t get resolved because I avoided discomfort? Your answers might surprise you, however they’re vital: You’ll not only learn a little more about yourself but also how you can improve your leadership. Bank Notes Does your bank have sufficient liquidity? According to an article in the most recent FDIC Supervisory Insights, liquidity analysis and risk assessment for financial institutions has become more complex in the last 15 years. Why? Changes in funding. Insufficient liquidity could cause a bank to fail, making liquidity a significant risk and uncertainty. Community banks are currently struggling to attract and retain core deposits. As a result, the banks are turning to alternative funding sources including wholesale funding such as federal funds, Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLB) advances, repurchase agreements and brokered deposits. Each has certain risks from a liquidity perspective. The FHLB continuously monitors a bank’s credit risk profile. In the event of asset quality deterioration, the FHLB may take various actions including refusing to renew advances upon maturity, accelerating repayment of advances due to covenant breech, raising collateral requirements or reducing funding lines. Lines of credit for many federal funds lines contain provisions allowing the correspondent bank to terminate the line or reduce the amount available to borrow at any time. Banking regulations limit the use of brokered deposits whenever a bank drops below “well capitalized.” Finally, Internet deposits have similar risks to brokered deposits as they involve premium rates, no relationship with the depositor and less stability. As many banks struggle to attract and retain deposits, many have altered their investment strategy from liquidity to yields. This may involve investing in longer term securities and more complex, riskier investments. Another liquidity risk is that the banks have been pledging their securities on FHLB borrowings. Often, the best or most liquid securities are those pledged to secure FHLB borrowings. Statement of Position (SOP) 94-6 Disclosure of Certain Significant Risks and Uncertainties requires disclosure in the financial statements about risks and uncertainties in four specific areas — nature of operations, use of estimates, significant estimates and vulnerability due to certain concentrations. SOP 94-6 says risks and uncertainties arising from concentrations should be disclosed when they could have a severe “impact in the near term” (i.e., within one year). Severe impact is defined as “a significantly financially disruptive effect on the normal functioning of the entity.” SOP 94-6 clarifies that severe impact is higher threshold than material, but less than catastrophic. Liquidity risk may be a significant risk for community banks due to the current economic environment, including the subprime market, and trends throughout the past 15 years. Bankers should consider whether their bank has sufficient liquidity to meet short term needs and appropriately disclose liquidity risks in the financial statements. FASB accounting standard, continued on page 3 there are some implementation issues that should be addressed, which include: • Allocating adequate resources in addressing the issues in FAS 157 • Developing an inventory of the fair value measurements (both recorded and unrecorded) which identifies the source of the fair value • Discussing with third party providers, who or what should be held to ensure that they understand the needs of the bank in developing the fair value measurements • Understanding the documentation and disclosure requirements for the fair values items Keep in mind, the previous information isn’t meant to be a complete argument of the issues or concerns surrounding the implementation of FAS 157. It highlights the central theme of the statement and is intended to assist bankers in getting focused on issues that need to be addressed to adopt this statement for interim and annual reporting in 2008. BankNotes 3 Bank Notes Inside this issue: • FASB accounting standard could create surprises for community banks • Be a fearless — not a fearful — leader • Does your bank have sufficient liquidity? 110 Veterans Memorial Blvd., Suite 200 Metairie, LA 70005 5100 Village Walk, Suite 202 Covington, LA 70433 Address Service Requested Information provided in this publication has been obtained by LaPorte Sehrt Romig Hand from sources believed to be reliable. However, LaPorte Sehrt Romig Hand guarantees neither the accuracy nor completeness of any information and is not responsible for any errors or omissions or for results obtained by others as a result of reliance upon such information. This publication does not, and is not intended to, provide legal, tax or accounting advice. For additional copies or change of address, contact LaPorte Sehrt Romig Hand. For more information, contact Susan Wright, at (504) 835-5522 or e-mail her at swright@laporte.com. Visit our Web site at www.laporte.com. Bank Notes January/February 2008 Printed in U.S.A.