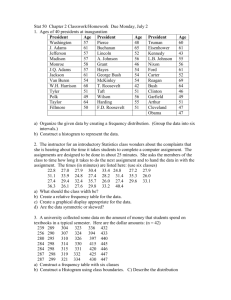

234 ] The Great Depression Roosevelt's campaign has historical

![234 ] The Great Depression Roosevelt's campaign has historical](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008354948_1-2c13592a7e1533172bc7683c52da422e-768x994.png)

234 ] The Great Depression

Roosevelt's campaign has historical importance, because the new techniques which he introduced have affected all campaigns since. They mostly revolved around personal attacks. He delivered a multitude of ghost-written speeches, some written by irresponsible or ignorant men.

His friend, Judge Samuel I. Rosenman, organized early in the campaign what became widely known as the Brain Trust. The working force appeared to be

Felix Frankfurter, professor of law at Harvard;

Raymond Moley, professor of public law at Columbia; Adolf A. Berle, Jr., associate professor of corporation law at Columbia; Joseph D. McGoldrick, assistant professor of government at Columbia; Rexford Guy Tugwell, professor of economics at Columbia; and Thomas Corcoran, a sometime instructor at

Harvard. Most significant of the group were Frankfurter and Tugwell, both devoted to "planned economy," the latter being the intellectual heir of Thorstein

Veblen. One or two other professors, who were originally drawn into the Brain

Trust, subsequently withdrew.

Nonacademic contributors to the Brain Trust included Louis Howe,

Roosevelt's secretary; Hugh S. Johnson, an able but vituperative former army officer; Basil O'Connor, Roosevelt's law partner; Donald A. Richberg, a railroad labor lawyer; Harry Hopkins, a professional social worker; Charles W. Taussig, a molasses millionaire, and Senators T. J. Walsh, Elmer Thomas, and George

Norris, three great masters of demagoguery.

It will appear later that this Brain Trust contained some men who were expert in semantics but grievously undernourished on truth.

Moley was an honest and convincing writer of speeches.

2

Hugh Johnson was, according to his account, a most influential speech writer.

3

2

Moley's book. After Seven Years (New York, 1939) is in considerable part devoted to showing how, when, and by whom Roosevelt's major speeches were ghost-written. He comments (p. 56) on

"the dreadful feeling of responsibility" the writing of the speeches entailed. Roosevelt's mind "was neither exact nor orderly. . . . He knew this because he seldom trusted himself to say in public more than a few sentences extemporaneously, though I doubt that he would admit that he is often inaccurate in casual conversation. I labored with the tormenting knowledge that I could not afford to be wrong."

3

Hugh S. Johnson also later wrote a book (The Blue Eagle from Egg to Earth, Garden City,

New York, 1935) in which he described the ghost-writing process in great detail and with pride.