this PDF file

advertisement

Pragmat ics 2:3.263-28O

InternationalPragmatics

Association

''TODAY THERE IS NO RESPECT'':

NOSTALGIA,"RESPECT"AND OPPOSITIONAL DISCOURSE

IN MEXICANO (NAHUATL) LANGUAGE IDEOLOGY

Jane H. Hill

1. Introduction

"Todaythere is no respect" (dxdn dmo cah resp€to)is one formula of a discursive

systemthroughwhich speakersof Mexicano(Nahuatl)in the Malinche Volcano regionof CentralMexico express"nostalgia"about daysgone by, in achtol. The discourseof nostalgiaconsistsof formulaic pronouncementson a restricted list of

themes:in achto,languagewas unmixed:no one knew, or neededto know,castilla

'Spanish,'but

insteadspokepuro mexicano. In Mexicano,ritual kinsmen greeted

eachother on the villagepaths,parentscommandedchildren,and neighborsspoke

to eachother of the ancient tasksof cultivation.Work was hard, but goods were

cheap,measuredin traditionalquantitiesand paid for with small coinswith ancient

names.Peopleate traditionalfoodswith Mexicanolabels,especiallyneuctli'pulque,'

fermentedfrom the sap of agaves.The interactionalqualities of in achto can be

summarizedas in achto 1catca respeb 'In those days, there was respect.' Today

peopleare educatedand know Spanish,but the Spanish is full of errors, and

children come out of schoolgroseros,rude and disrespectful.

The discourseof nostalgiais "ideological"in both the "ideational"and

"pragmatic"

senses(Friedrich1989).Not only is it made up of a set of propositions

aboutthe past,but. throughthe implicit and explicitpositiveevaluationsof the past

that the discourseasserts,people who benefit from practicesthat they believe are

Centralto the discourse

legitimated

by traditionput forwardtheir politicalinterests.

of nostalgiais a "linguisticideology" that suggeststhat the Mexicano language,

especially

in some "pure" form, is a peculiarlyappropriatevehicle for the social

formsof longago.irr achto,,

and especrally

for "respect."On the other hand,Spanish,

with the social

andthe mixingof Spanishand Mexicano,are peculiarlyassociated

formsof today,dxdtt,and with the loss of respect.

Whilethe discourseof nostalgiais universallyinterpretablein the Mexicano

townsof the Malincheregion.not everyoneproducesit. Most likely to repeat its

formulasare relativelysuccessful

men. Women,and men who possesslittle in thp

'

An earlier version of this paper was presentedat the S;"mposiumon Linguistic ldeology at

the Annual Meeting of the American Anthropological Association, Chicago, IL, Nov. 20-24, 1991.

I would like to thank participantsin the svmposiumand Lukas Tbitsipisfor their comments on drafts

of the paper.Wbrk on Mexicano \\'assupported by funding from the National Endowment for the

Humanties(NEH RO-2U95-'14-5'72),the American Council of lrarned Societies,and the Penrose

Fund of the American Philosophical Sociery.

264

JaneH. Hitt

way of the locally-relevantfrrrms of capital, seldom engage in the discourse.

Instead,they may produce an oppositionaldiscourse,contestingthe discourseof

nostalgia by exposing its formulas to contradiction and even to parody. This

"counter-discourse"

underminesthe termsof the linguisticideology,constitutingan

"interruption" (Silverman and Torode 1980) of the idea that particular trlrms of

languageare inextricablylinked to particular forms of social order. Further, this

interruption is more radical than are somewell-knownchallengesto languageform

and use in English. This may be becauseMexicano linguisticideologylocatesthe

crucial nexus of representationbetween dialogic action and social order, not

betweenreferenceand realitv.z

J

2. Nostalgia as a discursivesystem

Before turning to the counter-discourse,

I characterizewith greater precisionthe

content and organizationof the discourseof nostalgia.Its characteristicfilrmulas

developa smallset of major rhetoricalthemes: 1) "respect":the proper <lbseryance

of statusrelationships,especiallyillustratedby greetingsbetweencompadre.r'ritual

kin,' and commandsfrom parentsto reponsivechildren,contrastedwith t<tday's

groserta'rudeness',2) the sacrednature of the Mexicanocommunityand the ties

between its people, contrasted with contractual ties for profit, 3) a favrlrable

economy,in which goodswere cheap and life was rig<lnlusbut healthy,contrasted

with today's high prices and unhealthy ways; 4) cultivati<lnas the prototypical

human way of life, contrastedwith factorywork and schooling,seen as educational

preparationfor suchwork; 5) the useof Mexicanolong ago,vs. the useof Spanish

today; 6) the linguisticpurity of in achto,contrastedwith the languagemixing of

dxdn.3

These themes and their associatedf<lrmulasoccurred in sociolinguistic

interviewsconductedwith 96 speakersof Mexicanoin I I towns in the Malinche

Vo l canor egionbet w e e n7 9 7 4 a n d1 9 8 1 .N o s p e a kerusedal l of thesethemes,nrl r

did any speakerconnectthem in a coherentargument,either in the intcrviewrlr in

'

The distribution of the discourseof n<lstalgiaand its uluntcrdistx)ursc across groups in thc

Mexicano socio-scapeis not absolutc. Rrr instancc, Don Gabricl, whilc praising thc rigtr ol' oldcn

days, observes that his anc.estorswcre "enslaved',as indood thcy wcre (thcy wcrc bondcd laborcrs

o n a h a c i e n d a ) .O n t h e o t h e r h a n d , w o m c n w h i l e p r a i s i n g t h c o p p o r t u n i t i c s a v a i l a b l c t r i l a y , m a y

speak negatively of the rudenessr>fchildrcn rlr thc dangcr of crimc in thc citics.

3

Empirically, we can determine thar thc gcncral pattcrns ol borrowing lrom Spanish into

Mexicano, which permits loan vocabulary from cvcry grammatical catcgory of Spanish, wcrc wcllestablishedby the beginning of the lftth Ccntury (Karttuncn and l-rrckhart 19761.Thus not cvcn rhc

greal-greal-grandparentsof lhe oldest gcneration of u)ntcmporary Mcxicano spcakcrs livc<l in a

world in which there were no Spanishloans in Mcxicano. Notc that nostalgicdisrxrurscsarc rocordcd

f r o m a v e r y e a r l y p e r i o d i n M e x i c a n o c o m m u n i t i c s ;K a r t t u n c n a n d l , r r c k h a r t( 1 9 8 7 5n o t c a d i s q r u r s c

about a "golden age" in the Bancroft dialogucs, rc<xrrdodin ab<lut 157()-1511fi.

Thcir "Goltlcn Agc"

discourse reflects cln a time before the Cirnquest,whcn childrcn wcrc rigorously trainod and sin was

swiftly and sternly punished.

A m i n o r p o i n t o n M e x i c a n o o r t h o g r a p h y :t h c s y m b o lx s t a n d sl i r r I S J ,n o t I x J ,a s i s c x r n v c n t i o n ailn

o r t h o g r a p h i e so f t h e i n d i g e n o u sl a n g u a g c so f M c x i c x r .

Mexicano (Nahuatl) langtage ideologt

265

everydayconversation(where the discourseoccurredquite commonly).Instead,the

discourses

of nostalgiaoccur in fragments,with formulaic elementsscattered across

the hour or so of conversationin the averageinteniew, or used in passing in

conversation.Most speakersused only one or two formulas from the discourse of

nostalgia. Every theme was mentioned by at least half a dozen speakers

(sometimesthe use was in the context of the counter-discoursesdescribed below).

Most commonlymentioned were "mixing" and the change in greetings.

Three elderly men in three different communities produced the most

completedevelopmentsof the discourseof nostalgia,using many of its elements

during the interview. Each of these men had achieved high office in the civil-religioushierarchy in his community, and each claimed an identity as a cultivator, a

campesino.Don Gabriel (5734) mentioned the largest number of themes, using

commonly-heardformulas about respect, mixing, greetings, the language of

traditionalagriculturalpractice, the sacred,how cheap everythingused to be, how

peopleusedto work hard, and how the schools,while they teach Spanish,seem to

make childrendisrespectful. Don Gachupin (S12) mentioned the "doctrina," the

greetingof compadresas an indicator that "there was respect,"and the fact that

languagemixing occurs. Don Abr6n (576) produced routines on the Mexicano

languageof agriculture,the speechesappropriate to hospitality with pulque,

greetingcompadreson the road, and givingordersto children.None of thesethree

men connectedall theseelementsin a singleaccountor argument.

Since the "discourseof nostalgia" does not occur as a single coherent

argument,what is the justification for characterizingit as a singlediscursivesystem?

First, speakersoften chain more than one element. Especially common is to

exemplifya discussion

of "respect"with Mexicanogreetingscontrastedwith Spanish

greetings,

thoughtto be not respectful.Or a speakerwill mention language"mixing"

andimmediatelyturn to a mentionof the problemof respect.Exemplifyingchaining

of the languagethemewith the economictheme,Don Gabriel observedin response

to an interviewquestionabout domainsof Mexicanolanguageuse that in his youth

he spokeMexicanoin shops.He then amplified his reply by remarking that

(1)

"Everythingwas cheap then. You could buy chiles for a centavo, fish

for two centavos...everythingwas by the centavo,and by the cuanilla

[a unit of measure no longer used, about 6 pounds], and one

requestedit in Mexicano.Anyone would wait on us, and there was no

problem with short-weighting,like there is today."

One speaker illustrated"mixing"with a comparisonof Spanishdios and Mexicano

teotl'god,' linking languageuse to community sacralization.Or a speaker will

illustratethe Mexicanogreetings,and extendthe quotedconversation(the usualway

of illustratingthe greetings) to include discussions

of cultivation:

(2)

a

"Did the compadrewake up well?"

"Well,God be praised,passon, Compadre."

"And where is the compadregoing."

S73,speaker?3,andotherspeakernumbersgivenhere,refersto the list in Hill and Hill 1986:

456-59.

266

JaneH. Hitl

"Wh!, to the fields, to scrapethe magueyes."

"Muy the compadre passon."

Or, a person will observe that the reason that all children now speak Spanish

is

becausethey go to school,yet the schoolsdo not make them polite and obedient,

but rude and unruly. For instance,Don Gabriel, replying tb a question about

whether people spoke Mexicano better today or long igo, Jaid,

(3)

"It's the same. The same. But today they all want education,but

what good does it do? I tell you, it doesn'tdo any good. They even

go to secondaryschool, but they come out groseros.No longei do"t

it make them have more respect. I tell you, today everything is all

mixed up."

In addition to the chaining of rhetorical formulas and themes, speakers

express connections between the themes through rhetorical parallelism.

For

instance, Don Abr6n produced the figure in (4), where the iftcio "work,,

was

cultivation and the tlahtol "language"wis Mexicano.

(4)

ye n6n oficio... ye ndn totlahtOl.

'That

was the work then...thatwas our languagethen.'

Don Marcos (S83) used parallelism to associateMexicano with highly

desired

"respectful"ethical statesof "mutual trust" and "gratitude."Remarking that he still

spoke Mexicano with some people in his town, he said,

(5)

titlahtoah mexicano, timondtzah de confidnza.

'When

we speak Mexicano,we speak seriouslywith mutual trust'

Don Marcos felt that Mexicanowas an "inheritance"from the elders,and

said that

he urged this position upon his children,as follows:

(6)

mdcdmo md ye ingrdto, mdcttmo md quilcdhua in mexicano

'Muy

you not be ungrateful, may you not forget Mexicano'

In addition to syntagmaticchainingand paradigmaticparallelismin speech,

a more complex semioticlogic connectsthe varircusdiscourseiwith the geneialized

urtderstandingof "long ago." The discourseof nostalgiainvolves"multiplex

signs,,,

(Briggs 1989):elementsthat not only refer to, but call ip indexically,an entire

social

order associatedwith m achto. First, to mention the Mlxicano tanguag",

especially

legttimo mexicano 'correct, unmixed Mexicano' accomplishes ti'is. -S"conO,

th;

emphasison the sacredoccursin two highly routinizeddiscourses:the

idea that a

speaker in the old-daysw_horeally knew legttimomexicanoknew it hasta

la doctina,

'even

to the catechism.'Onespeakerstatesthat people spoke so well in achto

that

"even the hymnswere sung in Mexicano."Peoplecorn-only mention

that greetings

in the old days invoked the sacred:people would exchange,"Ave

Maie,,, ,,veras

concebida"[sic]. Such formulas place the sacredat the ,"ni., of Mexicano

usage,

paralleling the physicalplacementof churchesat the center of

communities,and

paralleling as well many rhetorical claimsthat constitutethe Mexicano

community

as a sacredspacesurroundedby a profane periphery (Hill 1990b,to

appear). Ani

note that the greeting formula connectsthis in turn to the order

of''iespectful"

sociality.

Mexicano (Nahuatl) langtage ideologt

267

Third, the Mexicanogreetingsbetweencompadres,

"co-parents"ritually joined

in a kinship-likerelationship,and the giving of orders to children in Mexicano are

especiallyfavored illustrations of the respectful order of in achto. These routines

require the production of verb forms which index the two most important axes of

socialdifferentiation in Mexicano communities,the relationship between ritual kin

and the distinctionbetween senior and junior blood relatives.The verbs must be

marked with honorific affixes (o. their meaningful absence) that index the

relationship

betrveenspeakerand addressee(Hill and Hill 1978). This point will be

developedfurther below.

The socialorder of in achto can also be indexedby mentioning cultivation;

hencethe useof conversationsabout agriculture to exempliff Mexicano speech.The

ideal of agricultural self-sufficiencyis constructedby mentioning the cheap prices

(and the measuresand coins) of bygone days.This is contrasted with the need to

find wage labor and the high prices of today. The language of the wage-paying

workplaceand of purchasingin shops, practices associatedwith dxdn, is Spanish;

this is confirmed by nearly all speakers. Speakersusually say that children acquire

Spanishbecausethey go to school, and that such schoolingis necessaryto prepare

for wage labor, but they argue that children come out of school "disrespectful."

Thusuniversalschoolingand literacy,in letrah,an important multiplex sign of dxdn,

is linkedsyntagmatically

to the idea of "disrespect."5

In summary, "nostalgia" in the Mexicano communities is accomplished

through a set of discoursesthat are intricately interlinked with one another, by

syntagmatic

chaining,by rhetorical parallelism,and by the fact that the principle

formulasof the discursivesystemare multiplexsigns.Accessingas they do the entire

order of.fu achto,such signspermit speakersto move from one of its elementsto

the other without bridging argumentation.The relative coherenceof this system

makesit possiblefor us to speak of nostalgiaas an "ideology"(cf. Eagleton 1991).

3. Pragmaticideologr in the discourseof nostalgia

A centralthemeof the discourseof nostalgiaexpresses

a "linguisticideology:" a "set

of beliefsabout languagearticulatedby usersas a rationalizationor justification of

perceivedlanguagestructure and use" (Silverstein7979: 193). Following Whorf,

Silversteinarguesthat the dialectical relationship betrveenideology, structure, and

usewill be constitutedprimarily through"referentialprojection"or "objectification,"

the projectionthrough which the structure of language- especially"pervasive

surface-segmentable

linguistic patterns" (1979: 202) - is reified as the structure of

theworld.Through "referentialprojection"pragmaticcategoriesare interpreted as

referential.For instance,tensemay be consideredto refer to units of time "in the

world,"not to pragmaticdimensionsanchoredin discourse.A form of "projection"

occursalso with pragmatic ideologies. The discourseof nostalgia claims that

Mexicanodialoguesare inextricablylinked to a desirablesocial order of the past,

and particularlyto "respect,"and that disrespect,a key problem of today, is linked

5

Women often agreewith the evaluation of today's children as rude and disrespectful; however,

they never blame this on schooling, which is very common in the discourse of nostalgia.

268

lane H. Hill

to the use of Spanish.These claimsfocus on usage,and are thus pragmatic. Such

ideologies, Silverstein argues, tend universally to exhibit certain characteristic

features. First, pragmatic ideology locates the "power" of language in surface-segmentableitems. Second,pragmatic function is held to be "presupposing"

rather than "creative" (ot "entailing"): the uses of language appear because

preexisting social categoriesrequire them. Third, pragmatic effects are held to be

extended from propositional ones.

Silverstein's first proposal, that the power of language will be located in

surface-segmentableelements,is borne out in the Mexicano caseby the fact that the

discourse of nostalgia utterly fails to notice the formal differences between the

signalling of deference and distance in Mexicano, by a complex system of verbal

suffixesand by honorific suffixeson other parts of speechas well (especiallynouns,

postpositionals,and discourse particles) and the morphology of deference in

Spanish. However, the discourse of nostalgia does not focus on "words," the

surface-segmentableelementpar excellence.6Instead,

the units chosenby Mexicano

speakersto illustrate"respect"are "surfacesegmentable"

only at the discourselevel:

they are whole dialogues,not singlewords or phrases.The salienceof such dialogic

units may link the pragmatic ideology of nostalgia and a more general theme of

community and sociality over individuality in Mexicano communities (see Hill

1990a).It may also be linked to a more generally"pragmatic"orientation toward

language in Mexicano language ideology, to be discussed further below. For

instance, in illustrating how respect was conveyedin greetings,many speakers say

somethinglike this:

(7)

In the old days, compadres would meet, and they would salr

"Mlxtonaltlhtzinoh?", "Mopandltihtzino" hudn "Mopanahuihtzlnoa

compadrito.""Did his honor wake up (well)?" ("Muy his honor pass

by," "The compadre is passinghonorablyby.") But today, it is puro

buenos dias, puro buenas tardes ("nothing but "Good day," "Good

afternoon.")"

Relevant here are the three verbs, appropriate to the first greeting of a

compadre on the path in the morning. Their structureis shown below:'

(7a) m-ixt6nal-tih-tzln-oh?

REFLEXIVE-WAKE UP-APPLICATIVE-HONORIFICTTHEMEPASTSING

'Did the daydawnuponhis honor?'

(7b) mo-pan6-l-tlh-tzin-o

REFLEXTVE-PASS-APPLICATIVE-APPLICATIVE-HONOR

IFIC..

THEME(IMP)

'Irt his honorpasson'

o

A routinized purist discourse,discussed

in Hill and Hill (1986)doesfocuson a short list of

legitimo mexicanolexical items.

7

Th. follo*ing abbreviationsappearin the examples:IMP = Imperative,INDEF = Indefinite,

OBJ = Object, P2 : Secondperson,P3 = Third person,SING = Singular.

Mexicano (Nahuatl) language ideologt

(7c)

269

mo-pana-huih-tzln-oa-h

REFLEXI VF,-PASS-AP PL I CAT I VE -H O N O R I F I CTTHEM E -PLU RAL

'His

honor is passingby'

Here, the level of honorific marking appropriate to interchangesbetween

ritual kin is indicated by verbs in the third person, even though the exchangeis in

directaddress.The verbs are marked also with the honorific suffix 4zin. used both

to the elderlyand ritual kin. They are also marked as reflexiveverbs,with the prefix

mo- and the applicative suffixes (-tih,-L, -huih in the dialogue above) that are

requiredto adapt the valence of these intransitive verbs to the presence of the

reflexiveprefix. These third-person honorific verbs contrast (1) with second-person

verbswith reflexive and honorific markings, appropriate for greeting persons who

deservereverencebut who have no ritual kinship relationshipwith the speaker,(2)

with verbswhich are reflexive but which lack the honorific suffix, which might be

usedfor a well-dressedstranger,(3) with verbs marked with the prefix on- "away,"

appropriatefor senior relativeswho are not elderlyr and (4) with unmarked verbs,

appropriatefor greetingchildren or same-generation,

same-sexblood kin.8

The SpanishgreetingsBuenosdias and Buenastardescontain no verbs, and

so can be used without constituting any particular relationship between speakers

beyondthe phatic.Furthermore, Spanish,even where verb forms and pronouns are

present,has only a two-way contrast of distance and deference, compared to the

subtlegradationspossiblein Mexicano.

Speakerswho illustrate the greetings nearly all say explicitly that the

Mexicanogreetingsshow respect,but that the Spanishgreetingslack it. Speakers

seemto be identiffing the difference in indexical force between the two types of

greetings,yet no speaker ever mentioned the affixes, or even observed that the

Spanishgreetingshad any sort of formal difference from the Mexicano ones.

Instead,speakersillustratedby contrastingcomplete greetingexchangeswith one

another,as above.Compadrazgo,ritual kinship, is the single most important social

relationshipbetweenadults, and "respect" (along with confianza,"mutualtrust,") is

the mostimportant element of this relationship,an element that is often articulated

by speakers.The invocation of the most characteristic everyday language of

compadrazgo,

the greetingon the road, can stand metonymicallyfor the respectful

socialorder of.in achto, "long ago."

Silverstein(1981) extendedhis theory of linguisticawarenessto permit a

continuumof salience.The Mexicano casesuggeststhat such saliencemay be linked,

not only to perceptual factors such as surface segmentability,but also to the

complexities

of local schemas.Commandsto children are mentioned only half as

oftenas greetingsbetween compadresin order to illustrate "respectful" Mexicano

speech.

The most likely reasonfor this difference is that the presenceof the affixal

8 Th. rpt.m is not perfectlyregular:the various

markingoptionsof honorific suffix,reflexiveapplicative

affixation,and prefixationwith on- ate variableat eachlevel; a verb form may haveone,

two,or all threeelements.Sometimes,compadresare addressed

in the secondperson.However,

third-person

directaddressoccursonly with ritual kin. SeeHill and Hill 1978for more detailed

discussion

of the honorificsvstem.

270

Jane H. Hill

systemon the verbs in the greetingsis in fact the object of awareness,although at

a level below that of "discursiveconsciousness"

(Giddens 1976).

The usual discourseillustratingcommandsto children goes something like

the following:

(8)

"In the old days, you could say to a child, "Xicui in cuahuitl, xiah

xitlapiati." ('Get the firewood, go take the stock to pasture.'), but

nowadays,who would understand?They might even say,"Don't talk

to me with that old stuff." You have to say, "Ttae la lena, vas a

cuidar."

lrt us examine the structure of the imperativeverbs in these expressions:

(8a)

(8b)

(8c)

MEXICANO

SPANISH

xi-c-ui

trae

IMPERATIVE-P3OBJ-BRING

BRING.P3

xi-yah

va-s

IMPERATIVE-GO

GO.Pz

xi-tla-pia-tih

IMPERAIIVE- INDEF,NONHUMAN.OBJ.-CARE-GO

In both cases,the verbs are unmarked for deference. In Spanish,with its

two-way distinction of distance/deference,trae "bring" and yas "you're going" are

contrasted with deferential taiga, vaya respectively. In Mexicano, with a more

complex system,the imperativesare contrastedminimallywith verbs that would be

used to an adult stranger: xicui vs. xoncui 'Bring,' xiah vs. xonyah 'go', and

xitlapiatih vs.xontlapiatih'Go take the stock to pasture.' Thus, while commands to

children illustratea socialrelationshipwhere respectis at issue,their linguisticform

alone (as opposed to the nature of the children'sresponse),since it is unmarked,

does not invoke respect.Nor does it contrast with the Spanishcommand which, at

this level of the system,is in exactly the same relationship of marking to a more

deferential alternative as is the Mexicano imperative.

Silverstein's second property of pragmatic ideolory, the tendency to see

indexicalig as "presupposing,"is helpful in understandingcharacteristic thematic

choices of the discourseof nostalgia.The most popular way to illustrate "respect"

is with greetings between ritual kin. This is the maximally "presupposed"social

category,outside of blood and marriage relationships.Relationshipsof ritual kinship

are created through formal ceremonies,after which the languageappropriate to the

relationship is used. The use of the correct language with compadres certainly

reaffirms the relationship,and it is through such usagethat the verbal distanceand

deference consideredappropriate to it is constituted.I have also heard speakers

attempt to enhance very distant claims of compadrazgo by using honorific

third-person forms. For instance,Don Abr6n used third-person address to the

American linguist Jane Rosenthal,who is a comadreof his comadre Dofla Rosalia.

Such usagessuggestthat people feel that there might be some transitivity in a chain

of the relationships,such that a person who is compadre to a compadre of a

prominent person,for instance,might be compadreof the prominent person more

directly. However, it is clear that the claimsthat speakersmight have upon, or the

honors that they might render toward, someone so addressedare very limited

compared to those on their formally-constitutedritual kin, and to derive from these

Mexicano (Nahuatl) language ideologt

271

factsthe social-constructionist

interpretationthat relationshipsof compadrazgoare

constitutedthrough languagecertainlywould not jibe with native theory.

There are honorific usagesoutsidecompadrazgowhich are probably more

constitutive

or "creative,"in contrastto the relatively"presupposing"usagebetween

compadres.

For instance,no ceremonymarks the transitionof a person to the level

of venerabilitythat prompts high levels of honorific usage to the elderly, and

speakersare not clear about exactlywhen they would do this ("to someonewith

white hair,"or "to someonewho walks with a cane" are examplesthat have been

suggested

to me). To some degree,then, recognitionas an elder is constituted

throughthe way others addressthat person,with the label momahuizotzin'your

reverence'substituted

for the pronoun tehhutltzfn,and with second-personhonorific

verbs.A few people illustrate "respect"by sayingthat, "In the old days,when you

would meet an old man, or an old woman, you would say ...", but this is less

commonthan the illustrationof greetingsbetweencompadres.

The failure of speakersto recognizecreativeindexicalityis evidencedby the

fact that no speakerrecognizesexplicitlya function of Spanishloan words that is

veryobviousto the outsider:the constitutionof the power of important people in

publiclife. Politicaldiscoursein the communitiesis densewith Spanishloans, and

bothhereand in other hindsof talk very high frequenciesof Spanishloan material

appearin the usage of important senior men. K. Hill (1985) has shown that

speakers

implicitlyrecognizethis fact by demonstratingthat a female narrator used

Spanish-loan

frequencyas one way of representingthe relative statusof figures in

a narrative.

Silverstein'sproposal that pragmatic ideologiestend to reduce usage to

referenceis not clearly illustratedin the discourseof nostalgia.Silverstein'smost

developed

illustrationof this tendencyis the caseof feminist linguisticcriticism in

English.He arguesthat feministscorrectlyperceivethe "pragmaticmetaphorical

relationshipbetween gender identity and status" (Silverstein 1985: 240), but

erroneously

locatethis in the systemof referenceand predication,especiallyin the

useof the genderedpronouns as noun classifiers,rather than in the intricate web

of pragmaticpatterning.Speakersin the discourseof nostalgia,however, locate

respectin formulaicdialogues,not in particularwords. This non-occurrenceof the

reductionto referenceis a manifestationof a basiclinguistic-ideological

bent among

Mexicanospeakers,to think of speechprimarily as action. I will enlarge on this

point below.

4. Counter-discourses

The discourseof nostalgiais produced primarily by two groups of people: senior

menwho are relativelywealthy and successfulin terms of having achievedhigh

positionin the local hierarchy,and young and middle-agedmen who have full-time

workoutsidethe communities.e

Not a singlewoman in our samplewas "nostalgic."

e While

theseare the two groupsof speakers

most likely to use Spanishloan wordsat high

frequencies

in speakingMexicano,they are also the two groupswho are most likely to mention

"mixing"

asan exampleof decline.

272

JaneH. Hilt

Instead,women strongly contestedthe idea that the old dayswere "better," and a

number of men, mainly poor elderly cultivatorswith little land and undistinguished

public careers,agreedwith them. Thesespeakersarguedthat the old dayshad been

extremely hard, and that many of the changesbetween "long ago" and "today" are

improvements. In articulating these ideas, they often produced what I call here

"counter-discourses:"

arguments that took specific formulas of the discourse of

nostalgia and exposedthem to explicit contradictionand, in the most interesting

cases,parody.

Example (9) illustrates contradiction. Speakerswho countered the discourse

of nostalgia strongly approved of education and literacy, and felt that the

bilingualism of today was a great improvement over the monolingual "ignorance"of

long ago. One elderly woman (Sa1) explicitly contradicted the discourse that

associatesschoolingwith disrespectand decline.She also suggeststhat bilingualism

is a favorable condition. She said.

(9)

"Listen, now I hear the kids studying,they learn Spanish, they even

learn L^atin.I hear the way they talk, even when they're playing. I

hear how they quarrel and fight with one another and I say,"Thank

God, it's worth somethingto read, not like the way we grew up, the

way we grew up was bad."

A second elderly woman (S54) turned an expression often used in the

discourse of nostalgia - in achto ficatca igdr "long ago there was rigor (high

standards,hard work, etc.)" - back upon itself, observingthat she had not been

allowed to go to school becausedmo ocotca ig1r "there was no rigor" - instead,

parents would hide their children from the teachers.

Several speakerscountered the nostalgicdiscoursethat offers orders to

children in Mexicano, and filial obedience, as an illustration of appropriate

traditional socialorder. Instead,they proposed,their own obedienceto their parents

brought them nothing but poverty and grief. One young woman (S28),who makes

and sellstortillas for a living, said,

(10)

"When we grew up this was the land of complete stupidity (tlro

t1ntotldlpan). Our parentsdidn't send us to school,they brought us

up "under the metate."It's not that way today: now, while the stupid

ones are doing the grinding,the young girls can escape,they can go

to school, they don't have to stay here. But as for us, no, because

what our father or our mother said to do was done. becausewe had

to.tt

An old man (S11) also interrupts the discourseof nostalgia.In the utterancebelow

he addressesit specifically,implying ("Who knows whether...?")that someone is

salng that the old people were better. In opposition,he suggeststhat obeying the

commandsof parents was not necessarilygood:

(11)

"We grew up simply in a time of misery. Now the old people are

gone,but who knowswhether they were better or more intelligent,or

whether perhaps they were stupider,eh? Well, who knows what is

the right way. Now the kids go to school.In the old daysthey put us

Mexicano (Nahuatl) langtage ideologt

273

to work. "Work, work!" they said, and off we'd go, but for what?

How did we grow up?"

DonaFidencia(S50)usedparody in addressingthis theme.In the following passage,

shereproducespreciselythe form of the discourseof nostalgia.But she inverts the

discourseof "giving orders to children" by illustrating orders from a child to a

mother:

(12)

"Well, now the children say,"Posmamd, vente;mamd, dame, o mamd,

quiero!'('Well, mama, come here; mama, give me, or mama, I want

something.') And long ago, no, they would say, "mamd, nicnequi

nitlamaceh, niutequi nitlacuaz, xinechomaca nin, xinechonmaca in

necah." ('Mama, I want to eat, I want to eat, give me this, give me

that.') And now, no, here any child will say,"Dame esto,mamd, deme

Usted,mamd." ('Give me this, Mama, give me, Mama.')

This exampleis exactly parallel to those of the discourse of nostalgia (in achto,

parentswould say that; dxdn, they have to say this), but interrupts it by suggesting

that there was no lack of disrespectand whining from children in the supposedly

more respectful"olden days"when children spoke Mexicano.

Some speakerschallenge the significanceof the change in greeting style,

obviously

replyingto the ubiquitousnostalgicvoice.An elderly man in Canoa (S13)

contrastedgreetingsin his own community with those in nearby [.a Resurreccin,as

follows:

(13)

Well, here it's "mt-xtdnaltthtzlno, mopanoltlhtzlno comadrita"(all

laugh),O.K., O.K., but listenhere, I'm goingto tell you, it's something

elsewhen you meet a comadre from [-a Resurreccin,well, there it's

"Bltenosdtas, comadita," but after all she'll still greet you back,

whether it's Mexicano or not, well it's still serious talk (monohn1tzah)

(generallaughter).

Parodyis availablein this domain as well. Thus Dofla Tiburcia (S78) used

parodyto counterthe illustration of the greetingbetween compadres- a particularly

scandalous

gesture,sincerelationshipsof ritual kinship are a very significant part of

localidentityand most people are quite sanctimoniousabout them. Exempliffing

thegreetingsbetweencompadres,she recited elaborate verb forms like those given

in examples(7) and (13). But the last line of her representedconversation,in

answerto whether the comadre is well, goes like this, and got a terrific laugh from

'her

proportionateto the scandal:

audience,

(14)

"Pozcualli, cualli comadita, contentos,mdzqui jodidos."

'Well we are well, we

are well comadrita, contented, but getting

screwed.'

The obviousimplicationof this remark is that elaboraterituals of respectbetween

ritualkindo not insulatepeople from life's vicissitudes,

or guaranteethat they will

alwaysspeakin a solemn and elevatedway. Note that this example was as close as

anyonecameto parodyingthe sacreddiscoursebetweenritual kin, which seemsto

be somewhatoff-limits to agnosticcritique.

274

JaneH. Hill

The obverse of the respectful Mexicano greetings is a practice that is

remarked on by many of our consultants,especiallythose in the towns along the

industrial corridor on the west flank of the Malinche: making obscenechallengesin

Mexicano to strangers on the road. Many consultantsremark that an important

reasonto know Mexicano is to be able to understandand reply to such challenges.

Against this background,Dofla Fidenciainterrupted the discourseof nostalgiawith

the following parodic witticism:

(15)

"Well, perhapsnow is better, you won't hear anybodysay,"Xiccahcaydhua in mondnalr," (Fuck your mother), now they'll say,"Chinga tu

madre."

Dofra Fidenciais clearlyaware of the discourseof nostalgia,and reproduces

its form ("Then, people said that, but now they say this") almost exactly - but the

content has changed.Sheis suggestingironicallythat nostalgiais misplaced: people

were as rude to each other in Mexicanoin the old daysas they are now in Spanish.

5. The discourse of nostalgia as political ideologr

Producers of the counterdiscourseobviously hear the discourseof nostalgia as

glossing over the dark reality of in achto, when there was violence, poverty, and

patriarchal control over the life chancesof women. Why would they care about ur

achto, however, if things have changed? What seemsmost likely is that producers

of the counter-discourserecognize that the discourseof "nostalgia"is in fact a

pragmatic claim on the present, using "pastness"as a "naturalizing" ideological

strategy: rhetorically, the claim is that those practiceswhich are most like those of

then, constitutea pragmatic

the past are the most valuable.The counterdiscourses,

claim on the future, when everyonewill have an equal chancefor educationand a

decent life.

The successfulmen who produce the discourseof nostalgiaclearly benefit

from socialrelationsof the type invokedin the discourseof nostalgia,whether their

successis manifestedby high positionwithin the communityhierarchy,or based on

resourcesaccumulated through wage labor. Control over family members, whose

labor can be summoned on demand. and an extensivenetwork of ritual kin who

cannot refuse requestsfor loans, are absolute prerequisitesfor a career in the

civil-religious hierarchy, the only fully-approved route to power within the

communitarian system. Men who depend heavilyon wage labor also have reason

to endorsethe "traditional system",and especiallythe secondaryposition of women

within it, to backstop their own forays into an uncertain labor market. Women

maintain households, often entirely through their own devices,while men work

outside the towns by the week or by the month. Nutini and Murphy (1970) found

that wage laborers were even more likely than cultivators to insist that their wives

and children live in virilocal extended families, thus increasing control over the

wives, usually through the agencyof the mother-in-law. Occasionsfor establishing

bonds of ritual kinship are actuallyproliferatingin the communitiesas wage labor

increasinglydominatestheir economies;ritual kinship,to a large degree,constitutes

the savings-and-loansystem in the towns. Thus for these groups, the order of

"respect" sustains them. For women, the order of "respect" is less obviously

Mexicano (Nahuatl) language ideologt

275

beneficial.Women who have been abandoned by their husbands,or who are

widows,may have great difficulty in finding ritual kin: peasantwomen, holding their

infantsand beggingprosperouspeople entering the church to stand up with them

to baptizethe babies,are not a rare sight in the city of Puebla.

6. "Enactive"pragmatic ideologr and radical challenge

Eagleton(1991)citesa distinctionmade by RaymondGeuss,between"descriptive"

and"pejorative"definitionsof the term ideology."Descriptive"or "anthropological"

definitionsassimilateideology to "world view": an "ideology" is simply a belief-system,and no judgementis made of its truth or value. In the "pejorative"definition,

anideologyis viewednegatively:becauseits motivationis to continuean oppressive

system,

becauseit involvesself-deception,or becauseit is in fact false, distorting

reality.

(1979,1985)use of the term "ideology"is certainly"pejorative":

Silverstein's

heseeslinguisticideologiesas distortingthe actualforms and functionsof language,

attendingto some at the expense of others. Moreover, he implies that such

distortions

will occuruniversallyin humancommunities,becauseof relativecognitive

limitationson human linguisticawareness.In emphasizingthat the distortions of

linguisticideologyare universal(with the salutory corollary that linguistic "science"

will be "ideological"),he predicts that the specific content of ideological discourse,

whetherit is hegemonicor counter-hegemonic,will simply replicate core category

errors,suchas the confusionof indexicalitywith reference and predication, and

reference

with the nature of the world. This "pejorative"attitude of courseextends

to the ideologyof resistance,as well as to the ideologyof domination. Silverstein

(1985)implies,in his discussionof feminist discourseand of the Quaker challenge

to the 17th-Century

Englishsystemof distanceand deference,that these category

erors doomcounter-hegemonic

discourseto political impotencyover the long run.

Is the Mexicanocounter-discourse

describedabovesimilarlyvulnerable? I believe

thatit is not, and that the radicalchallengethat it makesto the underlyingideology

is duenot only to the perspicacityand penetrationof thosewho produce it, but to

the broaderideologicalmatrix in which it is embedded.

The Mexicanosituationexemplifiesa subtypeof a version of the "enactive"

linguistic

ideologyidentifiedby Rumsey(1990),where languageis seenas embodied

in actionwith no distinctionmade between such action and reference. Rumsey

contrasts

thiswith the dominant"referential"linguisticideologyof the West,which

insists

on thedistinction(and,accordingto Silverstein,privilegesreference).Rumsey

arguesfor a relationshipbetweenideologyand formal patterning.Thus European

languages,

spoken in communities with the dualistic or referential ideology,

distinguish

formallybetween"wording"and "meaning,"while the oppositeis the case

in the AustralianlanguageUngarinyin, whose speakers exhibit the "enactive"

ideology.

Thesedistinctionsare illustratedin the examplesbelow.

Mexicanoformal patterning is distinct from that of Ungarinyin in the

representation

of reported speech.In Ungarinyin there is no distinction between

directand indirect discourseand thus, Rumsey argues,between "wording" and

"meaning"

at this formal locus.This is not the casein Mexicano,where documents

fromthe 16thCenturyshow clearlydevicesfor representingconstructeddialogue

I

i

j

]

i

276

JaneH. Hill

as indirect discourse.Thus indirect discourseis marked by deicticshift in the person

prefixes on verbs, as in the following example:

(16)

Yitic quimolluidya canah 1ztoc calaqutz

"In his heart he was sayingto himselfthat he would enter some cave."

Florentine Codex 12:9 (Dibble and Anderson 7975:26)

Contrast the unshifted person marker in direct discourse:

(17)

Quimolhuidya, "Cana oztdc rylcalaquiz."

He was saying to himself, "! will enter some cave."

However, Mexicano resemblesUngarinyin in that the "locution" of indirect discourse

is not formally distinguishedfrom "intentions."The formal verbal devicesfor such

indirect discourse under a locutionary verb are identical to those used under

affective verbs such as "want." Thus we find the following:

(18)

Quinequi calaquiz "He wants to enter."

(19)

Quihtoa calaquiz "He sayshe will enter."

Contrast this with the well-known formal distinctionsin English:

(20)

(2I)

(22)

(23)

He says[that] he will enter.

*He, saysto enter (where subjectof "enter" is he,)

He wants to enter.

*He, wants

[that] he, will enter.

In addition to the deictic shift illustratedin (16), modern speakershave borrowed

the Spanish particle que to introduce indirect discourse,or have extended the

semanticrange of the dubitative evidentialquil (which precedesa locution when

quoting speakerswant to distancethemselvesfrom the views of quoted speakers)

to calque on the meaningsof que.

MexicanoresemblesUngarinyinin cross-referencing

throughoutthe discourse

without any possibilityfor "ellipsis,"a term proposedby Halliday and Hasan (1973)

for situationswhere wording, as opposed to meaning,is inferred in English. In

sentenceslike: "John told all the girls everything,and Bruce did too," what is elided

is wording: "and Bruce told all the girls everythingtoo." The "girls"in questionneed

not, notoriously,be the same girls for Bruce as for John, so "meaning,"but not

"wording," -ay be distinct. In contrast, every Mexicano verb must encode the

complete argument structure of the sentencethrough pronominal prefixes. As in

Ungarinyin, such pronominal encodingof argument structurepermits speakersto

neglect full nominal referencefor long stretchesof speech.

Mexicano linguisticideology,like that observedin Ungarinyin by Rumsey,is

indifferent to the distinction between meaning and action. As I have pointed out

previously(Hill and Hill 1986),the Mexicano noun tlahtol means"word, language,

speech,"and does not discriminatebetweenstructureand use. Mexicano verbs of

speakingmay distinguishthe referentialfrom the rhetorical (for instance,contrast

tlapdhuia,"to tell a sto{, to relate,to chat,"(literally,"to count things",like English

"recount" or "account,")with ndtza "to summon, to speak with serious intent to

Mexicano (Nahuatl) langtage ideologt

277

someone,"

or naluatiT "to give orders"l0,but such differentiationis not required:

all of these are tloht1Lrr Consistentlywith this failure to differentiate form and use,

Mexicanospeakersdiscussing

the natureof languageemphasize,notdenotation,but

performance:the proper accomplishmentof human relationshipsas constituted

throughstereotypedmoments of dialogue.

Like the Ngarinyin, Mexicano speakers are prone to gloss forms in their

languageby illustrating a usage.However, in the case of Mexicano, this tendency

is highlyelaborated.The modern discourseof nostalgiacontinuesan ideological

patternapparentin the 16th Century. The forms of behavior appropriate to various

roles were encoded in memorized speeches,the hu€huetlahtolli, "safngs of the

elders;"a substantialbody of theseorations,and related formulasfor a wide range

of occasions(ranging from the utterancesappropriate to the installation of a new

emperorto thoserequiredof a midwife upon the deliveryof a baby),includinglong

sequences

of exchangesof courtesies,were recordedby the Franciscanmissionary

Bernardinode Sahagrinin the 16th Century.Karttunen and l,ockhart (1989) have

translatedan etiquette book, prepared by a Nahuatl-speakingmaesto for the use

of missionaries

in the late 16th Century, that illustratesthe formal exchangeof

courtesies

in manycontexts.Thus,Mexicanospeakersappearto feel that a language

consists,not in words with proper reference that matches reality, but in highly

ritualizeddialogueswith proper usagematchedto a socialorder that manifestsan

idealof deference.l2

The counter-discourseto the Mexicano discourseof nostalgia is produced

withina linguistic-ideological

matrix that seemsto be largelypragmatic or "enactive,"

inattentiveto the "referential"dimension. Thus the counter-discourse,and the

discourseof nostalgiaitself, exhibits a distinctive type of ideological projection.

Ideologicalchallengers

in Englishattackby arguingthat usagedoesnot appropriately representreality, and so must be changed.But according to Silverstein they do

not challengethe indexicalrelationshipbetweenreferenceand reality; this remains

covertand inaccessible.

Mexicano speakerswho use the rhetoric of the counterdiscourse,

feministschallengingclaimsthat women are inferior,

like English-speaking

interruptthe explicitrepresentationsof the nature of the socialorder produced in

l0 In *r. anyone

is tempted,Karttunen(1983),suggeststhatnahuatid,"to give orders,'is not

relatedto ndhuat(i) "to speak clearly, to answeror respond" (the source of nahuatlahtOlli"the

Nahuatle

language').

The latter form has a long initial vowel.Only in Ramirezde Alejandro and

Dakin's(1979)vocabularyof the Nahuatl of Xalitla, Guerrero is the form for "to give orders"

with a long initial vowel.All other sourcesgive the first vowel in nahuatidas short.

attested

1l I do not knowwhether

speakers

makethe assumptionclaimedby Sweetser(1937)for English

speakers:

thatif someone

sayssomething,theybelieveit to be true, andsincebeliefsare unmarkedly

whatis saidis true. It is the casethat to quote someonewith doubt is the "marked"case:

sinc€re,

thespeaker

mustusethe dubitataiveevidentialquil. However,speakersalso use the word 'lie" to

meananystatementthat turns out to be wrong, not just a statementuttered with the intent to

(mmparableto the exampleof.menrira'lie' cited by Briggs(1989)).

mislead

12lnfrrt, Mexicanospeakers

did not valueplain languageand literalism.lron-Portilla (1982)

haspinted out that the knowledgeof metaphoricalcoupletssuchasin xdchitlin cutcatl'theflower,

thesong'(poetry),in atl in tepetl'thewater,the mountain'(city), andin tlt in tlapalli'the black ink,

themloredink' (history)constituteda highlyvaluedform of knowledge.

I

278

JaneH. Hill

the discourseof nostalgia,by pointing out that there has alwaysbeen rudenessand

disrespectin society.Ties of compadrazgo,Doa Tiburcia suggests,do not prevent

anyonefrom "gettingscrewed."Obeyingthe ordersof parentsdid not bring success

for old Feliciano, who asks, "And for what?", or for Dofla Eugenia, who grew up

"under the metate." But the counterdiscourse

goesfurther, challengingnot only the

representation,but the link between languageand reality. If Mexicano speech

permitted rudenessand misery,and Spanishobviouslydoes the same,then the core

of the linguisticideology,that the order of languagestandsfor the order of society,

can be directly dismissed.Thus for Dofra Fidencia,languageis irrelevant: a person

can say "Fuck your mother" in any language.

Dofla Fidencia's attack on Mexican language ideology may be more

fundamentalthan are thoseconstitutedin similarcounterdiscourses

in English. This

may be so becausein "enactive"as opposedto "referential"ideologiesthere is only

one projective link, as shown in Figure I.

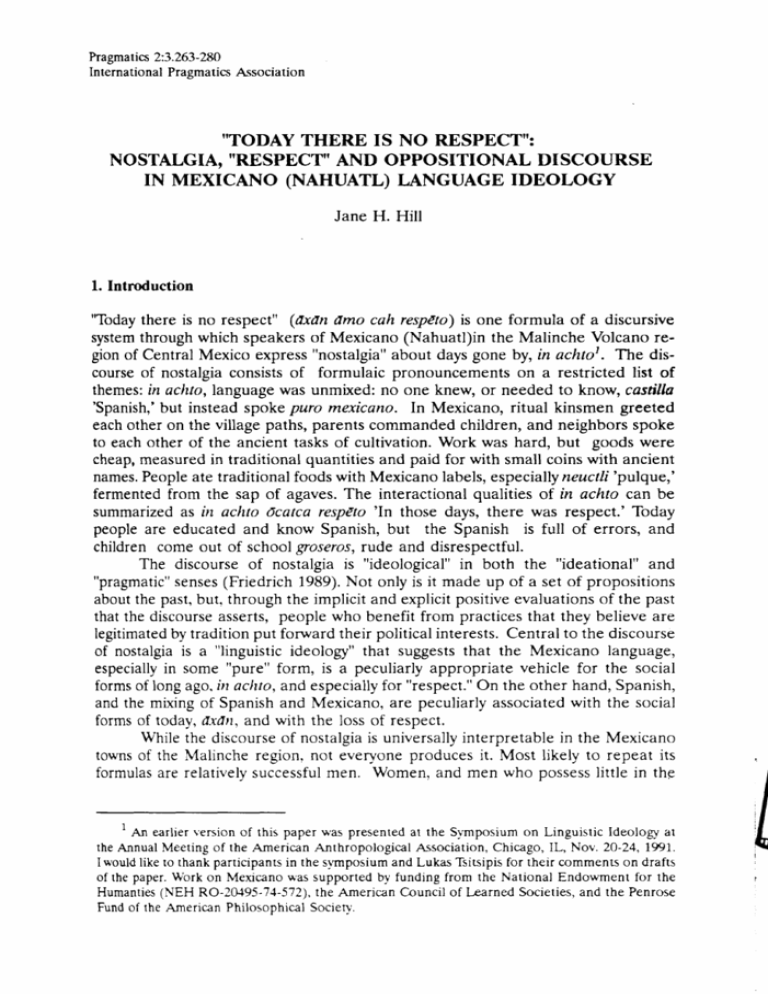

REFERENTIAL IDEOLOGY (e.g. feminist counterdiscourse):

Change usageto

preserve the relationship befween reference and reality

Usa ge= : :

: ll: : : :

)

fe fe fe n C e:::

= = :::

) S OC i al

feal i ty

ENACTIVE IDEOLOGY (e.g. Mexicano counterdiscourse):There is no link

between usageand reality

U s a g e= : = : : : :

=: - ll- -:

=::

=: =: ==:: ) SOCia

f el a l i t y

FIGURE I. Loci of Intemtption (ll) for Counterdiscoursesin Reference-basedand

Action-based Language Ideologies

Is there a feedbackfrom ideologyto structurein the Mexicano communities,as in

Silverstein'scase of the triumph of the pronoun "you" in English in responseto

Quaker linguistic ideology? The situation is obscure and paradoxical. While

legftimoMexicano (Mexicano without Spanishloan words) is an important metonym

of the order of "respect"in the discourseof nostalgia,it is preciselythe groupsmost

likely to indulge in the discourse of nostalgia who speak Mexicano in a very

hispanizedway. On the other hand, women and low-statusmen, the groups who

argue in favor of bilingualismand who reject the discourseof nostalgia,speak the

least hispanized Mexicano and are most likely to speak poor (or no) Spanish.

Silverstein predicts correctly the distorting effect of linguistic ideology; neither

producers of the discourseof nostalgia,nor producers of the counterdiscourse,

recognize the most obvious function of Spanish loan words, which is to mark

elevated Mexicano registersin which the discoursesof power in the communitiesare

conducted.The result of this failure is a nostalgicpurism which makes demandson

Mexicano speech that cannot be satisfied. Ampliffing the dissatisfaction with

Mexicano (Nahuatl) language ideologt

279

Mexicanothusinducedis the obviouslow statuswithin the communitiesof precisely

their"mostMexicano"members- memberswho cannot,becauseof their low status,

embody"respect."Suchcontradictions,alongwith the evidenteconomicadvantages

yi.tO languageshift and the lossof Mexicanoin the Malinche towns. It

of Spanish,

,..rr posibl" thai enictive language ideology may make such language shift

marginallyeasierto accomplishthan within a reference-basedideologicalmatrix,

wheie the indexicallink between reference and "reality" remains even after the

projectionfrom usageto referenceis under attack.

The example of the linguistic-ideologicalcomponent of the Mexicano

discourseof nostalgiaadds to the list of caseswhere a "linguistic ideology" is

obviouslypart of i "political ideology." The example shows, however, that the

resistancemust be understoodwithin their specific

of counter-hegemonic

dynamics

will

include the nature of the indexical projections

this

thit

and

matrix,

cultural

forms.

within particular linguistic-ideological

constituted

References

Briggs,C. (1989) Competencein Perpm'rance. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Eagleton,T (1991) Ideolog. [,ondon: Verso.

Friedrich, p. (1939)

9l:295-312.

"l-anguage, ideology, and political economy." American Anthropologist

Giddens,A (1976) New Rulesof Socioto$cal Method. New York: Basic Books.

Hill, J.H. (1990a)"The culrural (?) context of narrative involvement." In Bradley Music, Randolph

Gracryk,and Caroline Wiltshire,(e ds.),Papersfrom the 25th Annual Regional Meeting of the Chicago

LinguisticSocie|, Part Two: Parasessionon Language in Context, pp' 138-156. Chicago: Chicago

LinguisticSociety.

Hill, J.H. (l990b) "ln neca gobierno de Puebla: Mexicano penetrations of the Mexican state'n In

JoelSherzerand Greg Urban (eds.),Indian and Statein Latin Ameica,pp.72-94. Austin: Universiry

of fbxas Press.

Hill, J.H. ('lb appear) "The voices of Don Gabriel." In Bruce Mannheim and Dennis Tbdlock

(eds.),I/re Dialogic Enrergenceof Culrure. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Hill, J.H. and K.C. Hill (1978) "Mexicano honorifics.' Language 54:173-55.

Hill, J.H. and K.C. Hill (1986) Speaking Mexicano. Tircson: University of Arizona Press.

Hill, KC, (1985)"I:s penuriasde dona Maria: Un andlisissociolingiiisticode un relato del ndhuatl

moderno."Tlalocan10:33-115.

Karttunen,E and J. L,ockhart (1916) Nahuatl in the Middle Years: Language Contact Phenomena

inTuts of the Colonial Peior). University of California Publications in Linguistics 85.

Karrrunen,F. and J. l,ockhart (198?) The Art of Nahuatl Speech:The Bancroft Dialogues' Nahuatl

StudiesSeriesNumber 2. Los Angelcs, CA: UCLA l-atin American Studies Center Publications'

280

Jane H. Hill

kon-Portilla, M. (1982) "Three forms of thought in ancientMexico."In E Allan Hanson ( ed.),

Studiesin Symbolismand Cultural Communication,pp.9-24. University of KansasPublications in

Anthropology 14.l-awrence,KN: Universityof Kansas.

Nutini, H. and T Murphy (1970)"[.abormigrationand familystructurein the Tlaxcala-Puebla

area,

Mexico.' In W Goldschmidtand H. Hoijer (eds.),TheSocialAnthropologtof Latin Ameica: Essays

in Honor of Ralph Leon Beals, pp. 80-103.l,os Angeles,CA: UCLA latin American Center.

Rumsey,A (1990)"Wording,meaning,and linguisticideolory."Ameican Anthropologist92:346-36I.

Silverman,D. and B. Ttrrode(1980)TheMateial Word.l,ondon:Routledgeand Kegan Paul.

Silverstein,M. (1979) 'l:nguage structureand linguisticideolory.' In Paul R. Clyne, William E

Hanks, and Carol L. Hofbauer (eds.), The Elements:A Parasession

on Linguistic Units and Levels,

pp.l93-247. Chicago:ChicagoLinguisticSociety.

Silverstein,M. (1981) "The limits of awareness.'WorkingPapersin Sociolinguisrics

84. Austin:

SouthwestEducationalDevelopmentl^aboratory.

Silverstein,M. (1985) 'language and the culture of gender,"In Elizabeth Mertz and Richard

Parmentier(eds.),SemioticMediation,pp.219-259.New York: AcademicPress.

Sweetser,

E. (1987)'The definitionof 'lie'.nIn DorothyHollandand Naomi Quinn (eds.),Culrural

Models in Languageand Thought,pp. 43-66.Cambridge:CambridgeUniversity Press.