10 Don'ts For Press Releases Writing A Press

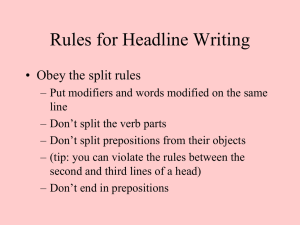

advertisement

10 Don’ts For Press Releases • • • • • • • • • • Don’t type your press release in capitals Don’t type your press release in italics Don’t type your press release on both sides of a page Don’t fail to proofread your release – or, better still, have it proofed by someone else Don’t use clichés Don’t use padding (‘with regard to’ ‘in the context of’) Don’t send it late (some provincial papers stop taking copy much earlier in the week than you might think – check with them) Don’t send it to the wrong person – or the right person with their name wrongly spelled Don’t use bold type to emphasise points in your release Don’t open quotation marks and forget to close them Writing A Press Release The hope animating the writer of any press release is that, when it’s finished, the release might appear in the newspaper, unchanged. If that is to happen, the press release must read the way stories in that paper read. Obvious? In theory, yes. In practice, no. Some organisations send four page press releases, filled with words like ‘infrastructure’, ‘peripherality’ and ‘subsidiarity’ to broadsheet and tabloid newspapers. The end result is that the stories rarely appear in the tabloid papers: because they’re not presented in the way tabloid newspapers write their stories, which is: Short/ not long Accessible, not obscure. There is a strong case for sending different types of press releases to different media. A story presented as a radio script and written in the spoken word has a much better chance of getting on radio than the same story presented in the written word. A number of key principles are common to all good press releases: 1. 2. 3. 4. A good press release has a good headline A good press release answers the key questions in the first paragraph A good press release uses active verbs and first degree words A good press release keeps the Fog Index in mind 1. A Good Press Release Has a Good Headline Each and every day, we are all bombarded, inundated with information from radio and the headline on a news story is like a free sample. It gives us a flavour of what the overall story is about. If the headline does not grab us, we are unlikely to read the rest of the story. Therefore, it may not matter how good the story is if it has a poor headline on top. This is a poor headline: Infrastructural Upgrade Enabled By EU Allocation Of €300,000 Following Campaign Related To Peripheral Areas Policy Directive Here’s what’s wrong with it: • It’s too long. 16 words is twice too long. A great headline can be spoken in one breath. • It’s full of what Hazlitt called the ‘big, grey words of the lexicon’. If you sit in a bus and listen to ordinary people talking, you’ll listen a long time before you hear words like ‘infrastructure’ or ‘policy directive’. Headlines should always be in the language of the reader not the writer. • It’s passive. ‘Enabled by …’ is an indirect, passive way of saying something. (Passive language is dealt with in more detail on page 12). • It’s in the past tense, so it sounds historic rather than newsy This is a good headline: New Road Cuts Traffic Jams In Half • • • • • • • It’s short. Tells the story in seven words It’s in vivid simple language It’s active: ‘Cuts traffic jams..’ It’s got human implications. (Most of us have been stuck in traffic jams.) It’s in the present tense, so it’s newsy (The future tense would work equally well: ‘New Road Will Cut Traffic Jams in Half’) It’s imaginable. We can see traffic moving freely When you’re writing a headline, remember that there is no obligation on the reader to pay any attention to it. The obligation is on you to attract the reader. It’s pointless to say ‘but they should be interested in this’. There are no ‘shoulds’ in mass media. You have to attract and persuade people to read your story: they have a million and one alternatives. The onus is on the writer, not the reader. And that applies throughout the writing of your press release. 2. A Good Press Release Answers the Key Questions in the First Paragraph Why? For two reasons: 1. If you story gets into the paper, and another, bigger story comes along before it goes to print, they will edit your story. Under pressure, a sub-editor will simply chop off the end of it. So your story must be understandable, even if what follows the first paragraph were chopped off. 2. Readers are busy and distracted. They may not have the time to read every story to the end. So you want to deliver the key information early, just in case. The key questions are: What (is happening)? Who (is involved)? Where (is it happening)? When? Why? 3. A Good Press Release uses Active Verbs and First Degree Words This sentence uses the passive form of the verb: ‘The town hall was occupied by protestors.’ This sentence uses the active form of the verb: ‘Protestors occupied the town hall.’ Remember, if it’s a headline, don’t just go for an active verb, go for a present or future tense verb: Protestors Occupy Town Hall Protestors to Occupy Town Hall Here’s the easiest way to remember this rule: BAD: Man bitten by dog (passive, past tense) GOOD: Dog bites man (active, present tense) FIRST DEGREE WORDS are the terms we automatically use: Boat Book Face SECOND DEGREE WORDS are the terms we use when we want to be more varied or impressive: Vessel Volume/Tome Countenance In order to understand a second-degree word, we almost have to relate it to its first degree equivalent. In news stories – and in press releases – first-degree words are better, because they don’t make the reader work. Use of first-degree words is sometimes described as the KISS rule: Keep it Simple, Stupid 4. A Good Press Release keeps the Fog Index in mind The Gunning Fog Index is about sentence length. Based on observation of the pattern of attention given by readers to printed material, it suggests that the longer a sentence, the thicker the ‘fog’ through which the reader has to get the message. 8 – 10 word sentences are clear and easy to understand 10 - 15 word sentences are slightly less clear and easy to understand. 15 – 25 word sentences mean that the fog is thickening 25+ can mean the sentence becomes impenetrable. The following sentence, for example, has 67 words: ‘through optimisation of mass media publicity opportunities while ensuring correct presentation of visual identification materials, it is possible to highlight opportunities available to potential beneficiaries of Structural Funds through the portrayal of successful projects already extant and at the same time alert members of the general public to the role played by the Member States together with the European Commission in the process of developing the regions.’ It would be much more easily understood if it were broken into five or more sentences. (It would also help if it used first-degree words like ‘Logo’ instead of ‘visual identification materials’). A shorter sentence version might read like this: ‘Successful projects are the best way to show what Structural Funds do. Potential beneficiaries get to see what opportunities exist. And the general public learns how the Commission and Member States are helping disadvantaged regions. These projects would be publicised in all media to make sure the message reaches everybody. The Structural Fund logo would always be used so people remember the name.’ [Ends]