Sociology 101: The Social Lens

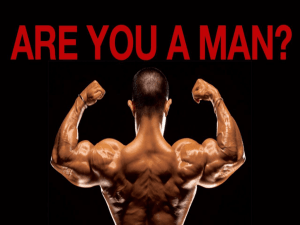

advertisement

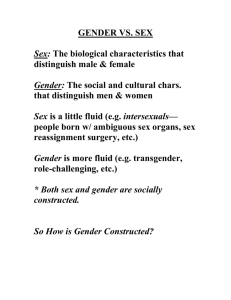

Sociology 101: The Social Lens Unit 8 Overview: Gender Stratification As Gloria Steinem wrote: Gender is probably the most restricting force in American life, whether the question is who must be in the kitchen or who could be in the White House. This country is way down the list of countries electing women and, according to one study, it polarizes gender roles more than the average democracy . . . . Black men were given the vote a half-century before women of any race were allowed to mark a ballot, and generally have ascended to positions of power, from the military to the boardroom, before any women. Why are so few men homemakers and so few women CEOs of major corporations? Why do women have to “act like a man” to make it in the business world? Why are little boys told not to “act like a girl” if they get hurt and cry? The quote by Gloria Steinem, a famous women’s rights advocate, underscores the fact that stratification by sex and gender is prevalent in American society nearly ninety years after women were granted the right to vote and twenty-five years since the Equal Rights Amendment was made ratified. These situations may be explained by understanding how society shapes our conception of sex and gender. Sex and Gender Typically, we think of the terms sex and gender as having only dichotomous possibilities: male/female, and masculine/feminine. Yet, as seen through the Sociological lens, these classifications do not capture the reality and diversity of individuals. They are each myths or social constructs in their own way. Sex A person’s sex is clearly linked to biological characteristics: XY vs. XX chromosomes, genitalia and other sex organs, hormonal levels, and secondary sex characteristics, such as muscularity, body hair, and breast development. Your text provides a brief overview of the biology and explains that “nature makes women and men different, but these differences do not add up to female 1 inferiority or male superiority” (Thio 2007; 267). Great variation and overlap does exist in the biology of males and females. Recent understanding of the variety and diversity of combinations of chromosomal, hormonal, and physiological body types has challenged the traditional conception of male and female. Medical science now recognizes individuals whose chromosomal makeup differs from their other sex characteristics; a condition known as intersexuality. Only about 1% of the population may be said to have “non-standard” sexual characteristics (http://www.isna.org/faq/frequency). While a small percentage, this may still cause us to reconsider the biologically defined division between male and female. In fact, it may be argued that sex itself is a social construct as society interprets biological differences and assigns an individual to the categories of male or female. Hegemonic Masculine Hegemonic Feminine Gender In the United States, gender is often considered along a continuum of masculinity and femininity. At the poles of the continuum would be the hegemonic male (tough, muscular, rugged) and the hegemonic female (soft, demure, sexy) with a range of gender types in between. However, many psychologists and sociologist agree that this bi-polar model is too limiting to explain the array of gendered expression in society. In fact, Cornell University psychologist Saundra Bem devised the Bem Sex Role Inventory (BSRI)1 to test a person’s masculinity and femininity as independent scales or axes, thus allowing for combinations such as high masculinity and high femininity, and low masculinity and low femininity. 1 Take the BSRI at http://www.neiu.edu/~tschuepf/bsri.html 2 Femininity Low M & High F High M & High F Masculinity Low M & Low F High M & Low F Gender Socialization While sex is linked to biological determinants, gender is clearly shaped by society through a process of socialization. Your text explains, “however a society defines gender roles, its socializing agents pass that definition from generation to generation” (Thio 2007; 268). These agents of socialization (the family, school, peers, the media, the church, and other institutions) begin shaping individuals as soon as they are born. Primary socialization, occurring between infancy and adolescence, is instrumental in shaping our gender identities. The family plays a central role during this period and has been found to reinforce gender stereotypes: “females were socialized to be dependent, fragile, unaggressive, sensitive, nurturant, and hesitant to take risks. Males were seen as being socialized in the home to be strong, confident, independent, and daring” (Peters 1994). 3 Gender Roles Socialization reinforces gender roles. These social roles influence our life choices, from what toys a child plays with, what a person may study, and even the jobs they may consider. They also shape our thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. Gender roles tell us what is the appropriately gendered way to express anger or sadness, when to be aggressive or passive, and when to speak or be quiet. Inequalities: Education, Work and Politics Just a few decades ago, it was expected that based on gender roles, a woman would get married, remain at home to raise her children, attend to the home, and take care of her husband (see The Good Wife’s Guide). Few options were open to women who wanted to pursue a career outside of “acceptable” fields like teaching or nursing. Education for the few women who completed a higher degree was limited mostly to women’s colleges. Interestingly, while fewer men today are enrolling in higher education, women are still found in greater numbers in majors that lead to lower-paying professions. By all measures, women earn less than 75% of the pay of men (Institute for Women's Policy Research). More importantly, Gettings et al. (2007) point out that though women work in almost equal numbers to men, “only eight Fortune 500 companies have women CEOs or presidents, and 67 of those 500 companies don't have any women corporate officers.” This lack of women in corporate leadership roles has been seen as evidence of a “glass ceiling” limiting women’s advancement and parity with men. Additionally, women have been almost entirely barred from political life. Until the 1920s women could not vote. In recent years women have made only modest gains limited in part by what Thio calls a “double bind.” He explains, “If a woman campaigned vigorously, she would likely be regarded as a neglectful wife and mother. If she was an attentive wife and mother, she was apt 4 to be judged incapable of devoting energy to public office.” Disproportionality may clearly be seen in the number of women elected to public office. Though 51% of the population is female less than 2% of seats in the Senate have gone to women; there have only been 35 women senators in 219 years. Things have only improved marginally; currently 16 women are seated in the Senate.2 Gender has also become a central issue in the 2008 presidential campaign (see Baird 2008, and Devney 2008). Sociological Perspectives According to Functionalists, the clear division of labor into men’s jobs and women’s jobs made it easy for members of a society. As expectations were assigned by biological sex, it made it easily known what one should do in a given situation. However, according to the Conflict Perspective, there was an inherent power imbalance in the patriarchal system that favored men and has lead to the inequalities we see today. Agents of socialization are slow to change and still reinforce many of the characteristics of patriarchy. This socialization may be studied by Symbolic Interaction, especially in the relations between men and women as they enact gendered roles. 2 http://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/resources/pdf/chronlist.pdf 5