Determining the Appropriate Definition of

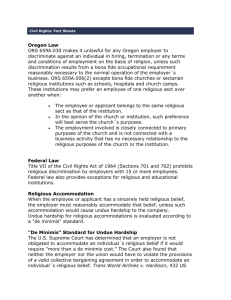

advertisement