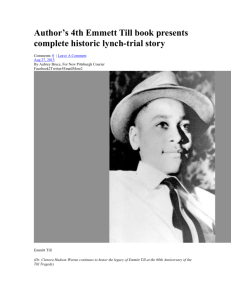

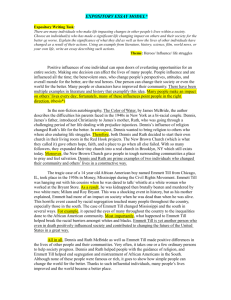

Tell Emmett Till author final

advertisement