Not Just Another Participation Model

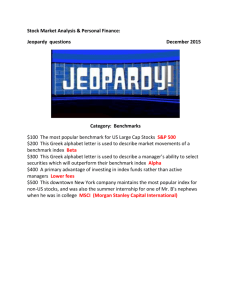

advertisement