Open/Closed List and Party Choice: Experimental Evidence

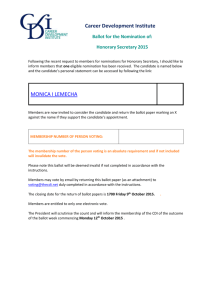

advertisement

Open/Closed List and Party Choice:

Experimental Evidence from the U.K.

Jack Blumenau

Andrew C. Eggers

Dominik Hangartner

Simon Hix

London School of Economics

Abstract

Existing research comparing open-list and closed-list PR electoral systems has

highlighted the way in which ballot type affects candidates’ electoral strategies.

We depart from this literature by emphasizing that ballot type may also affect the relative success of different kinds of parties. When voters have strong

opinions about an issue on which major parties are internally divided, open-list

ballots give voters an opportunity to express their preference on that issue without having to support a “niche” party. We provide experimental evidence of

this phenomenon from the UK, where we show in hypothetical European Parliament elections that using an open-list ballot would shift support from UKIP

(the Eurosceptic party) to Eurosceptic candidates of the Conservative Party.

This version: July 2014.

We thank the Electoral Reform Society and the LSE for generously supporting the research for this paper.

I. Introduction

Within electoral systems using proportional representation (PR), two types of ballots are

in wide use: in closed-list systems, voters choose among parties, with the order in which

candidates take seats being fixed within parties; in open-list systems, in contrast, voters

choose among candidates, with the order in which candidates take seats determined by

individual candidate vote totals. By giving voters influence over not just the number of seats

each party wins but also which candidates from a given party win seats, open-list systems

introduce a measure of intra-party competition among candidates. Political scientists have

argued that this intra-party competition tends to reward candidates who have more local

background and experience1 and increases the incentive for elected politicians to deliver

particularistic service to their voters2 and even engage in corrupt activities.3

While the literature helps us understand how different ballot types in PR systems affect

legislative behavior, it offers fewer clues about how ballot type affects parties’ relative

electoral success. This omission is puzzling not just because political scientists have a

strong interest in the consequences of electoral systems for party systems, but also because

the partisan consequences of ballot type should be of first-order importance to the actors

most responsible for choosing electoral systems — partisan politicians. Understanding

these consequences may thus help us understand how specific features of electoral systems

are chosen.

In this paper we argue that there are important situations in which ballot type is

likely to affect party electoral strength in PR systems. With reference to a simple spatial

model, we show that ballot type matters for party vote choice when candidates differentiate

themselves from co-partisans under open lists, and when the degree of this differentiation

differs across parties. We argue that this “differential differentiation” is especially likely

to take place, and thus ballot type is especially likely to matter for party choice, when a

1

See Shugart, Valdini and Suominen (2005) and Tavits (2009).

See Ames (1995a); Carey and Shugart (1995); Crisp et al. (2004); Hallerberg and Marier (2004);

Ashworth and Bueno de Mesquita (2006); Grimmer, Messing and Westwood (2012)

3

See Chang (2005) and Chang and Golden (2007).

2

1

salient issue intersects the dominant (left-right) dimension of political conflict. In such a

situation, some parties mobilize on the cross-cutting issue, adopting a clear and unified

position on the issue, while other parties are internally divided and either adopt centrist

positions or fail to express a coherent position. For convenience, we follow Meguid (2005),

Adams et al. (2006), Ezrow (2008), and Wagner (Forthcoming) in using the term “niche

parties” to describe parties that mobilize on cross-cutting issues; we refer to other parties

as “mainstream” parties. Our main contention is that support for niche parties is likely to

be weaker in an open-list system than in a closed-list system. Under a closed-list system,

mainstream parties lose voters to niche parties because voters with strong opinions on

a cross-cutting issue can only express those opinions by supporting a niche party that

mobilizes on the issue. Under an open-list system, by contrast, candidates from mainstream

parties can individually adopt clearer positions on the cross-cutting issue, such that voters

can find a mainstream-party candidate who shares their views on the cross-cutting issue.

Put differently, voters who would be torn between a niche party and a mainstream party

under closed lists can “have their cake and eat it” under open lists by voting for a particular

candidate from a mainstream party who shares their position on the cross-cutting policy

issue. To the extent that many voters find themselves in this position, niche parties attract

more vote under closed lists than under open lists, while the reverse is true for mainstream

parties.

We document this effect of ballot type on party vote choice in the context of a survey

experiment focused on British elections for the European Parliament. In these elections

(as in European Parliament elections elsewhere), the standard left-right dimension continues to organize political debate but there is a particularly salient additional dimension of

conflict between pro- and anti-integration views (Hobolt, Spoon and Tilley, 2009; Hobolt

and Wittrock, 2011; Ferrara and Weishaupt, 2004). In Britain, this second dimension is

highlighted by the rise in support for the “Eurosceptic” United Kingdom Independence

Party (UKIP). UKIP is on average to the right of the Conservative Party on many issues,

but primarily mobilizes on the question of Europe. In contrast, the mainstream parties

2

in the UK, and particularly the Conservative Party, are internally divided on the issue of

Britain’s relationship with the EU. British elections for the European Parliament serve as

a helpful test case for our theory because a significant number of center-right voters in the

UK are attracted to the Conservatives’ general policy positions (for example on economic

issues) but are also sympathetic to UKIP’s more clearly Eurosceptic stance on the question of European integration (Ford, Goodwin and Cutts, 2012). In this context, we expect

that many voters who would support UKIP in a European Parliament election under a

closed-list contest would prefer to vote for a Eurosceptic Conservative candidate if given

the opportunity under open-list competition, as this candidate would be closer to them on

both a general left-right policy dimension as well as the cross-cutting issue of European

integration. Indeed, our experiment shows that UKIP performs considerably worse under

open lists than closed lists (19% vs. 25% of respondents in our survey) while the main

parties perform better (particularly the Conservatives, who win about 28% vs. 22%). We

show that this occurs because Eurosceptic voters abandon UKIP in favor of Eurosceptic

candidates from the mainstream parties, particularly the Conservatives.

Understanding the partisan consequences of ballot type within PR systems is of clear

policy relevance in elections to the European Parliament, which take place under closedlist PR in some countries (including Germany, France, Spain and the UK) and open-list

PR in many others. Some policymakers have called for the adoption of open lists in all

European elections (e.g. Duff, 2011), and our analysis indicates that such a reform would

tend to bolster mainstream parties at the expense of Eurosceptic parties. More broadly,

ballot type could have partisan consequences in situations where environmental parties

rise to prominence (as happened in Europe with the Greens in the 1980) or when antiimmigration parties attract support and mainstream parties are internally divided on the

issue, as has occurred more recently. We recognize that the results of our survey depend

heavily on our assumptions about the kind of candidates who would emerge in open-list

competition, and we acknowledge that the findings are most directly applicable to the

particular context of British MEP elections. Still, we contend that the theoretical insight

3

applies more broadly and may help to predict what would happen under ballot type reform

in a variety of contexts.

Methodologically, our study departs from most previous work on electoral systems by

relying on a survey experiment rather than observational data. One could address the

same question with a cross-country regression, but in European elections (and other types

of elections, as discussed in Eggers (Forthcoming)) the countries that use different electoral

systems typically differ in many other respects; this tends to make causal inferences depend

heavily on modeling assumptions.4 Our experiment removes much of the ambiguity of

observational approaches by allowing us to observe whether similar voters facing the same

basic choice behaved differently when shown a different type of ballot. While it is of course

impossible to perfectly simulate the circumstances under which voters would cast ballots

in a real election (let alone vary those circumstances in a fully realistic way), we believe

the results provide unusual clarity about the likely effects of an electoral reform with broad

relevance.

II. List type and party choice: theoretical expectations

In this section we highlight mechanisms through which changing between open-list PR and

closed-list PR could affect party choice. We first introduce a simple spatial framework in

which we represent open-list PR as a system in which candidates from the same party can

adopt different positions; we then show that parties that allow such differentiation may

benefit more from the adoption of an open-list system than parties that do not. We argue

that open-list systems in fact encourage diverse positions but that parties differ in the

extent to which they respond to this electoral incentive. Finally, we apply these insights to

the case of EP elections in the United Kingdom.

4

For example, countries that use open lists for EP elections are much smaller on average, were admitted

to the EU later, have a higher district magnitude, and a lower level of public trust in the EU (Commission,

2013).

4

A. The electoral consequences of differential differentiation

We focus on a spatial model of politics in which voters vote expressively, i.e. they choose

the candidate or party whose platform is closest to their own ideal point. By assuming

expressive voting, we sidestep questions about what electoral outcomes voters expect, how

voters believe delegations of MEPs decide voting positions once in the European Parliament,

etc.; in this model, voters simply vote for candidates or parties whose positions they like.5

For an expressive voter, a move from closed-list to open-list elections affects party choice

whenever the closest candidate to the voter under open list is not from the party that is

closest to the voter under closed list. The key question in determining how ballot type

affects party vote shares, then, is the degree to which the candidates of a given party

spatially differentiate under open lists.

Figure 1 makes the point in the simplest possible case, with two parties and one dimension of political conflict. Under closed lists (top panel) we assume that each party has

a single platform, with party L to the left of party R. Of course, in practice there may

be a diversity of views among the candidates on a party list. Our assumption is that an

expressive voter who is asked to choose among parties in a closed-list system views each

party as if it occupied a single ideological position, which may be the position occupied

by the top candidate on the list or the average of the candidates’ positions. The vertical

dashed line indicates the cut point separating the ideal points of voters who support party

L (to the left of the cut point) from those who support party R (to the right of the cut

point).

Now suppose the election is held under open lists. In the middle panel of Figure 1 we

assume that candidates from both parties adopt positions that are distinct from the party’s

perceived closed-list platform. Candidates LR and RL adopt positions more centrist than

the party position under closed lists, but because both parties offer centrist candidates the

5

The same basic conclusions can be derived in a model with strategic voters (i.e. voters who cast votes

in order to affect which candidates are elected, considering the likely votes of others); we discuss this

approach in the Appendix and provide evidence that such strategic behavior may have been limited in our

experiment.

5

Figure 1: Ballot type and vote choice as a function of intraparty differentiation: one

dimension

L

R

Closed lists

LL

LC

LR

LL

LC

LR

RL

RC

RR

Open lists,

both parties

differentiate

Open lists,

party L

differentiates

R

Note: Two parties compete for votes under closed-list PR (top panel) or open-list PR (bottom two panels).

The vertical dashed line in each panel separates ideal points of voters who would vote for the L party (left

of the dashed line) from voters who would for the R party (right of the dashed line). An open-list system

allows candidates to adopt positions distinct from the party’s perceived platform under closed lists. Given

expressive voters, the L party gains support if its candidates differentiate and the R party’s candidates do

not (bottom panel); the shaded region identifies the ideal points of voters who support L under open lists

and R under closed lists assuming that R does not differentiate.

6

cut point does not move and party vote shares are the same as under closed lists: any voter

who was closest to L under closed lists is closer to LR under open lists than to the most

moderate R candidate (RL ).

Finally, in the bottom panel of Figure 1 we assume that the parties differ in the extent

to which individual candidates stake out differentiated positions. In this case, candidates

from the L party differentiate while those from the R party do not. This moves the cut

point to the right and convinces voters with ideal points in the shaded region to change

their support from R to L.

The same arguments can of course be extended to multidimensional politics. To take

the simplest multidimensional case, consider a situation in which there are two parties and

two issues, and on each issue politicians can adopt just two possible positions, e.g. {Left,

Right} on the first dimension and {0,1} on the second dimension.6 With closed lists, each

party is associated with a pair of positions; with open lists a party’s candidates can adopt

positions that are distinct from one another.

In Figure 2 we illustrate the effect of ballot type on vote choice in this simple twodimensional spatial model. In the left panel, we show a closed-list situation in which party

L occupies the {Left, 1} policy position and party R occupies the {Right, 0} policy position.

In the center panel, both parties diversify on the second dimension, in the sense that we now

have party L candidates at both {Left, 1} and {Left, 0} and we have party R candidates

at both {Right, 1} and {Right, 0}. This leads to voters with ideal points in the two shaded

regions changing support from one party to the other (compared to the closed-list case);

without making assumptions about the distribution of ideal points we cannot say how this

would affect party vote shares. In the right panel, the L party differentiates on the second

dimension while the R party does not; as in the one-dimensional case in Figure 1 this leads

to voters with ideal points in the shaded region changing their vote choice from party R

to party L. As with the one-dimensional case above, a change from closed-list to open-list

ballots benefits the party that differentiates more.

6

The assumption of binary policy options simplifies the notation but is not necessary for any of the

points we make. Note that we assume a continuum of voter ideal points.

7

Figure 2: Ballot type and vote choice as a function of intraparty differentiation: two

dimensions

Open lists,

both parties

differentiate

Closed lists

1

L

1

R

0

Left

Right

0

L1

R1

L0

R0

Left

Right

Open lists,

party L

differentiates

1

0

L1

L0

Left

R

Right

Note: Under closed lists, we suppose that party L and party R occupy different positions on both

dimensions (left panel). In the central panel, we suppose that both parties differentiate on the vertical

dimension under open lists; voters with ideal points in the shaded region change their party vote, with

ambiguous implications for overall party vote shares. In the right panel, we suppose that only party L

differentiates on the vertical dimension, causing voters in the shaded region to change their party vote from

R to L and leading to an increase in support for party L. We view the right panel as a fair representation

of the (short-term) effects of introducing open-list ballots to a competition between a mainstream party

(L) and a niche party (R).

8

B. The likelihood of differential differentiation

The foregoing analysis makes two simple points: parties face an electoral incentive to allow

diverse positions in an open-list system, and voters’ choice of parties will depend on the

ballot type if some parties internally differentiate more than others. We now present some

evidence that such differentiation actually happens under open-list elections, and that this

differentiation is likely to differ across parties in a predictable way. We use this evidence

to motivate our experimental design in the next section.

Research on open-list systems emphasizes candidates’ efforts to differentiate themselves

from their co-partisans in terms of effort (Cain, Ferejohn and Fiorina, 1987; Ashworth

and Bueno de Mesquita, 2006; Bräuninger, Brunner and Däubler, 2012), ability to deliver

legislative ‘pork’ (Ames, 1995a,b; Crisp et al., 2004; Hallerberg and Marier, 2004; Grimmer,

Messing and Westwood, 2012), and other valence characteristics (Shugart, Valdini and

Suominen, 2005; Tavits, 2009). Less emphasis has been placed on the policy positions

adopted by candidates, but the same logic certainly applies.7 Intra-party competition in

an open-list system clearly provides incentives to the party to allow such differentiation (as

highlighted in the previous section). Candidates may also find that they can attract more

preference votes by staking out a distinct position from their co-partisans. Anecdotally,

MEP candidates from the same list do stake out different policy positions in countries using

open-list ballots. In Denmark, for example, voters can visit a website that enables them

to find which EP candidates are most compatible with their own positions; the candidates’

stated positions on the key issues show clear diversity within parties.8 More systematically,

in analysis of roll-call votes in the European Parliament we find that party cohesion is lower

in countries using an open-list system to elect their MEPs. (See regression results in Table

3.)

Why should we expect the level of differentiation to differ across parties? One important

7

For example, Samuels (1999, 492) argues that “Politicians in every party in candidate-centric electoral

systems . . . can seek votes by either distributing pork or adopting policy positions.”

8

The

TV2

candidate

test

is

available

(as

of

10

June,

2014)

at

http://politik.tv2.dk/kandidattest/kandidater.

9

reason is that parties differ in the degree to which their members agree on salient issues,

particularly when it comes to certain issues that cross-cut the main dimensions of political

competition. For example, many mainstream parties in Europe are deeply divided on

immigration, while anti-immigration parties are relatively unified (Geddes, 2003). Given

open-list competition, voters could choose among a diversity of viewpoints on immigration

within these mainstream parties, while candidates from anti-immigration parties are likely

to continue to present a unified anti-immigration viewpoint.9 Of course, the logic outlined

above suggests that all parties would have an incentive to offer candidates occupying a

variety of policy positions; whatever the existing diversity of viewpoints within a party, that

party would face an electoral incentive to recruit candidates whose positions would appeal

to opposing parties’ voters. It is clear, however, that there are counteracting incentives, and

that these incentives vary across parties. For example, some parties may prefer to field a

unified set of candidates in order to present a more cogent policy vision to the electorate; in

some parties the leadership may have such strong policy preferences that they are unwilling

to allow alternative positions for the sake of the party’s overall electoral support. Many of

the same arguments that are made to explain why parties do not converge to the median

in electoral competition (Grofman, 2004) could thus be used to explain why some parties

may not present a fully diversified set of candidates. Because these forces (e.g. the strength

of elites’ policy convictions, the importance of a given issue to a party’s brand) may differ

across parties, differentiation may also vary across parties.

Applying this logic to European politics, we should expect differential differentiation

wherever the salience of European integration differs across parties. A clear example of

this difference is between mainstream and Eurosceptic parties in European Parliament

elections. Eurosceptic parties place high salience on the issue of European integration,

and define themselves by their opposition to to the current design and operation of the

EU. They compete against mainstream parties that originate from and mainly compete

in national politics on a variety of other issues – such as the key economic and social

9

With reference to the right panel of Figure 2, we see the mainstream party as L (able to adopt both

positions on the second dimension) while the anti-immigrant party, R, is unable or unwilling to do so.

10

policy questions that make up the contemporary left-right dimension of politics in Europe

– and hence place less relative importance on the issue of European integration. These

mainstream parties tend to have positions on Europe that are more vague, more variable

over time, and more diverse within the party. This idea – that parties that put higher

salience on the European question are more united on the issue – is confirmed by an expert

survey (Bakker et al., 2012) that we analyse in Table 4. The regression shows that parties

viewing European integration as high-salience are significantly less likely to be internally

conflicted on the issue.10 Anecdotally, this relationship also emerges in attacks launched

by Eurosceptic parties criticizing MEPs from mainstream parties for failing to vote in

parliament according to a party line.11 With reference to the right panel of Figure 2, we

see a mainstream party as the L party, with candidates adopting both pro- and anti-Europe

positions on the second dimension, while a Eurosceptic party is like party R, with all of its

candidates bound to an anti-Europe platform.

C. Corresponding expectations for European elections in Britain

Drawing on the previous analysis, what expectations do we have about the effect of introducing open-list ballots into British MEP elections? Under an open-list system, we

expect candidates within the major parties to adopt a variety of positions on European

integration. One reason for this is that all of the major parties have shown some degree

of internal division over the question of European integration. These divisions have been

clearest among Conservatives, with Conservative MPs and MEPs openly expressing Eurosceptic views that go well beyond the party line,12 but elite dissent is also visible in

10

We define a party as high-salience on European integration when the mean expert survey score for

the party is one vote-weighted standard deviation above the vote-weighted mean. This measurement

strategy closely resembles the one used by Wagner (Forthcoming) in the definition of ‘niche’ parties. The

dependent variable measures expert responses to the question: “[How much] conflict or dissent [was there]

within parties over European integration over the course of 2010?”.

11

See for example Morten Skaerbaek, “Venstrefolk stemmer vidt forskelligt i EU-parlamentet”, Politiken,

5 October 2013 (link).

12

See e.g. Nicholas Watt, “David Cameron aims to stare down Eurosceptic rise within Tory ranks”, The

Guardian, 26 May 2014 (link).

11

the Labour Party13 and, to a lesser extent, among the traditionally strongly pro-Europe

Liberal Democrats.14 Supporters of the major parties also express a variety of viewpoints

toward European integration. We observe this in our own survey, as documented in Table

5: although respondents supporting Labour, the Greens and the Liberal Democrats show

a clear pro-Europe tendency, between one-quarter and one-third of respondents expressing

a preference are Eurosceptic, while the reverse is true for the Conservatives. The existence

of disagreement within a party does not of course mean that each viewpoint will be represented by a candidate on an open-list ballot. As discussed above, however, there is an

electoral incentive in an open-list system to field candidates with distinct viewpoints who

can appeal to different voters, and we expect that this logic would not be lost on party

leaders and strategists. Another reason to expect a diversity of candidate positions within

major parties is that recent elections (particularly the 2014 election) have highlighted pervasive voter scepticism toward Europe, resulting in strong showings for UKIP. The major

parties may respond to this situation by becoming more Eurosceptic, but if competition

takes place under open-list PR we expect some candidates to respond more quickly than

their party. Thus both existing disagreement and electoral incentives are likely to lead

major-party candidates to adopt diverse views on Europe under open-list competition.

In line with the arguments presented above, we do not expect similar differentiation

by UKIP candidates – at least not on the pro- vs. anti-Europe dimension. Euroscepticism

is such a core element of UKIP identity that voters would have little idea what a proEurope UKIP MEP candidate stood for. In other words, we assume that when faced with

open lists, we would observe differential differentiation between mainstream candidates and

UKIP candidates. Because we will later refer to this assumption, we state it formally here:

Assumption 1: Under open lists, the mainstream parties would field candidates with a va13

See e.g. Peter Dominiczak, “Labour split over EU referendum, Jon Cruddas suggests”, The Telegraph,

19 Sept 2013 (link); George Eaton, “Labour divisions over EU emerge as MPs launch pro-referendum

group”, New Statesman politics blog, 13 May 2013 (link).

14

See Mary Ann Sieghart, “They are all Eurosceptics now”, 10 October 2011 (link).

12

riety of positions toward European integration. UKIP would field uniformly Eurosceptic

candidates.

Given the analysis above, Assumption 1 implies the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Under open lists, UKIP would lose votes to other parties – particularly the

Conservatives, given their proximity on economic issues.

Further drawing on the analysis above, Assumption 1 also implies that there would not be

much net movement of votes among the mainstream parties:

Hypothesis 2: Assuming that the mainstream parties all differentiate on the European

integration dimension, a change in ballot type should not result in substantial net exchanges

of vote share among these parties.

In the next section we introduce the experiment we designed to test these hypotheses.

III. Experimental Design

Our experiment was embedded in a survey conducted by the research firm YouGov and

fielded between June 26 and July 5, 2013. The survey was administered to a random sample

of N = 9096 panelists who are, according to YouGov, representative of British adults in

terms of age, gender, social class and newspaper consumption. For all analyses below, we

use probability weights provided by YouGov to weight the survey to the national profile of

all adults aged 18 or older.15

For the core of the survey experiment, we asked subjects to vote in a hypothetical

election for European Parliament. All subjects were shown a ballot listing three candidates

from each of five parties (Conservative Party, Green Party, Labour Party, Liberal Democrats

15

The analysis below includes all respondents. However, when discarding all respondents who took under

two seconds or over 100 seconds to answer any of the pre- or post-ballot questions (over 1000 respondents

in all), which addressed attitudes toward Europe, party identification, and ease of using the ballot, the

results are almost exactly the same.

13

and UKIP).16 Half of the subjects (chosen at random) were shown a closed-list ballot and

asked to pick a party; the other half were shown an open-list ballot and asked to pick a

candidate. As discussed above, our principal interest is in how parties’ vote shares depended

on ballot type.

As a general matter, ballot type could affect party vote choice only if voters have

preferences not just between parties but also among the candidates within parties. Given

that the candidates in our experiment are all fictional, any preferences that our survey

respondents had among candidates could only come from information we provide. We

thus had to think carefully about what information to provide. A first question involved

how much information to provide about the candidates. Ideally, we would like to provide

candidate information similar to what a British voter might acquire during the several

weeks of an election campaign, when (depending on campaign behavior, which is likely to

depend on ballot type) the voter may receive fliers from various candidates and parties,

watch debates, read endorsements, etc.; unfortunately, such a large and nuanced amount

of information could not realistically be communicated in the few seconds that survey

respondents can spend learning about fictional candidates for our experiment. Ultimately,

we decided to provide a subset of respondents with limited but clear information about

the candidates’s positions on Europe: in addition to a name (and thus gender) and party

affiliation, each candidate was endorsed by a (fictional) pro-integration pressure group

called “Britain in Europe”, a (fictional) anti-integration pressure group called “Britain

Out of Europe”, or neither. Respondents received this information in two steps: first they

were shown a screen explaining the endorsements and listing the endorsed candidates (as

shown in Figure 3); on the next screen they were again shown the endorsements alongside

the ballot as a kind of “voter guide” (as shown in Figure 4).

A second question involved the nature of the endorsements we would assign to each

16

We chose a set of fifteen names (five female, ten male) from a web application that allowed us to

generate random British-sounding names. The names were randomly permuted on each ballot, such that

average party vote shares would not depend on voters’ preferences over candidate names; we required,

however, that one candidate for each party should be female, such that voters’ preferences over candidate

genders would not introduce noise in party vote choices.

14

Figure 3: Endorsement information provided to respondents before voting

party’s candidates. As discussed above, we assume that intraparty disagreements about

European integration are likely in the major UK parties, but not in UKIP. Accordingly, for

each of the non-UKIP parties (Green, Labour, Liberal Democrat, Conservative), we had one

of the three candidates endorsed by the pro-Europe group, one endorsed by the anti-Europe

group, and one not endorsed by either. For UKIP, we assigned an anti-Europe endorsement

to all three candidates. It is therefore through the provision of endorsement information

that we hard code our theoretical assumption about ‘differentiated differentiation’ into our

empirical design.17

In order to disentangle the effect of the ballot type from the effect of the information

we provided to respondents, we designed the experiment as a two-by-two factorial design

(highlighted in Table 1) in which ballot type (closed- or open-list) and endorsement information (provided or not provided) are independently randomly assigned. Thus roughly

17

One objection to our design might be that we do not allow for variation in the number of candidates

‘endorsed’ by pro- or anti-EU pressure groups. For example, it might be more realistic for the Liberal

Democrats to have two pro-European candidates, rather than one. We acknowledge this, but feel that the

effects of the ideological balance of a given list of candidates on party vote share is a nuance that we cannot

fully examine in this design. This would, however, be a promising avenue for future work.

15

Figure 4: Excerpts from closed list and open list ballots, including endorsement information

Closed list (treatment group C)

Open list (treatment group D)

Note: Actual ballots (shown in Appendix Figures 8 – 11) provide more detailed instructions and include

candidates for all five parties.

16

one quarter of our respondents were given ballots like the one shown at the top of Figure

4 (treatment group C, in Table 1) and one quarter of our respondents were given ballots

like the one shown at the bottom of Figure 4 (treatment group D, in Table 1). Another

one-quarter (treatment group A) was given a closed-list ballot with no endorsement information and another quarter (treatment group B) was given an open-list ballot with no

endorsement information. This design allows us to address two potential objections to the

endorsement information we provided as part of our experiment.

Table 1: Design table

Ballot type

Information about

candidates’ positions

on European integration

provided?

Closed-list

Open-list

No

Treatment group A

n = 2251

Treatment group B

n = 2347

Yes

Treatment group C

n = 2260

Treatment group D

n = 2230

Note: Weighted sample sizes shown.

The first potential concern is about internal validity of the study: if we only showed

the endorsement information to respondents who are also given an open-list ballot, then it

would be impossible to disentangle the effect of the information we provide from the effect

of the ballot itself.18 The second potential concern relates to the external validity of the

study: if all respondents are shown this endorsement information, and if this information

is too divergent from the way in which voters typically think of the parties, then the effect

of ballot type we detect may be very different from the effect that would be seen if the

ballot type were actually changed. The factorial design allows us to address both concerns.

18

For example, if the Liberal Democrats do better under open lists, and endorsement information is only

provided to respondents shown an open-list ballot, the effect could be due to the fact that voters found

the party more attractive when they learned that the Liberal Democrats are not uniformly pro-Europe.

17

Clearly, because we can separately test the effects of the endorsement information and

the ballot type we can address the internal validity concern. The design also allows us to

address the external validity concern by testing whether the provision of information per

se affects party vote choice among respondents who are given a closed-list ballot. As we

show below, it did not, which suggests that our endorsements reflect positions on Europe

that are not too dissimilar from what voters might expect to see from each party.19

Another external validity objection could be raised, which is that the endorsement

information was provided in a particularly heavy-handed way. Granted, such endorsements

would never appear on an actual ballot paper; the information that voters receive about

candidates would tend to be much more noisy and multi-dimensional. On the other hand,

voters in a real election would have weeks to process the information to which they may be

exposed, and they would be able to actively seek out the specific information that may be of

use to them. (For example, “Which Labour candidate is most pro-integration?”) It is also

not unusual for voters facing complex ballots to be given voter guides by candidates and civil

society groups. We view our information treatment as a compromise made necessary by

the constraints of running a hypothetical election on survey respondents who have limited

time to process new information.

Before we proceed to the results, we first check the balance of the respondents’ covariate distributions across the four treatment groups. As expected from a randomized

treatment allocation, the tests show no sign of imbalance. More precisely, the p-values calculated from a joint F (3, N − df ) test of no differences between the 22 covariate means, all

measured pre-treatment, across the four treatment conditions follow the expected uniform

distribution over the [0, 1]-interval. Figure 12 in the Appendix plots the empirical distribution of the p-values from these balance tests against the theoretically expected uniform

distribution: since all p-values are above the 45 degree line, we can safely assume that

19

It is of course possible that the endorsement information changes voters’ understandings of parties’

positions but does not change overall party votes shares in the closed-list condition; for example, the

information that there are pro- and anti-integration Liberal Democrats might simultaneously make the

party more attractive (because more moderate than voters thought) and less attractive (because more

incoherent than voters thought), with no net effect.

18

randomization was successful. Table 6 in the Appendix shows the underlying covariate

means and corresponding F -tests across the four treatment conditions.

IV. Results

A. Main results: endorsements, ballot type and party vote shares

To evaluate the effect of ballot type on party vote shares, we separately compare the party

vote shares for the five main parties under the four treatment conditions indicated in Table

1; in particular, we run a separate OLS regression for each party in which the dependent

variable is 1 if the respondent chose this party (otherwise 0) and the regressors are a binary

indicator for Open List, a binary indicator for Information About Candidates, an

Interaction of the two indicators, and a constant. Table 7 presents the regression results.

Table 2: Main regression results of parties’ vote share by treatment conditions

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

(5)

GRN

LAB

LD

CON

UKIP

Outcome

Vote share Vote share Vote share Vote share Vote share

Open-list

-0.01

-0.00

-0.00

-0.00

0.02

(-1.18)

(-0.03)

(-0.33)

(-0.19)

(1.23)

With information

-0.00

0.00

0.00

-0.01

0.01

(-0.26)

(0.21)

(0.05)

(-0.71)

(0.62)

Open × information

-0.00

0.01

0.02

0.06∗∗

-0.09∗∗∗

(-0.09)

(0.24)

(1.30)

(2.70)

(-3.84)

∗∗∗

∗∗∗

∗∗∗

∗∗∗

Constant

0.12

0.30

0.10

0.24

0.25∗∗∗

(14.93)

(24.83)

(12.30)

(20.30)

(21.55)

Observations

9087.5

9087.5

9087.5

9087.5

9087.5

Note: Separate OLS regressions for models (1)–(5). Regression coefficients shown with corresponding t-statistic

in parentheses. All regressions are weighted using YouGov’s survey weights. * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

Note first that the constant term in each regression measures the proportion of respondents in treatment group A (closed-list ballot and no endorsements) who selected a given

party (12% for the Greens, 30% for Labour, 10% for the Liberal Democrats, 24% for the

Conservatives and 25% for UKIP). These proportions differ somewhat from the results of

the 2014 election,20 but they are quite close to the average of six polls that took place in

20

In the final polling, the vote shares were 8% for the Greens, 25% for Labour, 7% for the Liberal

19

2013 (the year we ran our survey).21 This highlights the representativeness of our sample

and suggests that our hypothetical ballot accesses the same preferences as more standard

vote intention questions.

The regressions indicate that neither the ballot type nor the endorsement information

has an independent effect on vote choice: in none of the five regressions does either coefficient approach statistical significance. The insignificant coefficients on “Open-list” indicate

that among respondents who were not shown any endorsement information about the candidates (treatment groups A and B), ballot type did not affect party vote choice on average.

This makes sense, given that respondents have no reason to prefer individual fictional candidates unless they know something about them. The insignificant coefficients on “With

information” similarly indicate that among respondents who were shown closed-list ballots (treatment groups A and C), the provision of endorsement information does not affect

party vote choice on average. This is reassuring evidence that the endorsement information

we provided roughly comports with voters’ perceptions of the parties and thus that our

evidence may be informative about what would happen if open lists were introduced.

We now turn to the interaction term in the regressions in Table 7, which indicates

how the effect of ballot type differs between the informed group (treatment groups C

and D) and the uninformed group (treatment groups A and B).22 The interaction term is

significant only for the Conservatives (who gain from open lists) and UKIP (who lose). This

finding is consistent with Hypotheses 1 and 2 above, which predicted that UKIP would

lose support because of its unified position on European integration while the mainstream

parties would not see much net exchange of votes. The Conservatives appear to benefit at

UKIP’s expense because of the parties’ relative proximity on other issues; we will further

examine this interpretation below. As can be expected from a randomized experiment, these

Democrats, 24% for the Conservatives and 27.5% for UKIP.

21

The average of these six polls for each party is as follows: Greens, 5%; Labour, 32%; Liberal Democrats,

11%; Conservatives, 23%; UKIP, 23% (UK Polling Report, 2014). The lower result for the Greens in other

2013 surveys may be due to the fact that other small parties were excluded from our survey.

22

Given the absence of an effect for the uninformed group, this approximates the effect of changing the

ballot type conditional on endorsement information being provided.

20

results do not depend at all on whether we include a large set of respondent characteristics

(respondent’s attitude toward Europe, socio-demographic characteristics, and previous vote

choice) in the regression.

Figure 5 presents the same results graphically. Based on the findings above, we focus

on the comparison of vote choice in treatment groups C and D (i.e. those who were given

the endorsement information).23 As seen in Figure 5, the Conservative Party gains about

6 percentage points (a 26% increase in vote share, with 95% confidence interval [.12, .40])

from a move to open-list competition. The mirror image of this shift is a corresponding

decrease in vote shares for UKIP, which loses about 7 percentage points (a 26% decrease

in vote share, with 95% confidence interval [-.38, -.14]). Consistent with Hypothesis 2,

we find no sizeable or significant effect for any of the other parties, i.e. Labour, Liberal

Democrats, and the Greens. Figure 13 in the appendix depicts party vote shares in all four

treatment conditions.

B. Subsample analysis: interactions with respondents’ party

identification and stance on Europe

Our theoretical analysis made clear that we do not expect the effect of ballot type to

be uniform across all voters. Specifically, we expect expressive voters with preferences

close to a mainstream party on one dimension, but close to the niche party on a crosscutting dimension, to be most likely to change party when moving from closed to open

lists (assuming that the candidates of the mainstream party differentiate). This subsection

examines which voters in our experiment are most affected by the change in ballot type

and, in particular, if these effects interact with respondents’ party identification and stance

on European integration.

Prior to participating in our experiment, survey respondents were asked, “If there were

a general election held tomorrow, which party would you vote for?” To understand which

voters are affected by ballot type, we run the same analysis as above (a separate regression

for each party, measuring the effects of ballot type, information provision, and interac23

It should be clear that the results are almost identical if we compare treatment groups A and D.

21

Figure 5: Effect of change from closed-list to open-list ballots on party vote shares

0.30

●

+0.01

●

+0.06

●

●

0.25

Party vote shares

●

0.20

●

−0.07

●

●

●

●

●

Labour Party

UK Independence Party

Conservative Party

Green Party

Liberal Democrats

0.15

●

+0.02

●

−0.01

●

0.10

●

Closed list

Open list

Note: Changes in party vote shares when moving from closed lists to open lists, given endorsement

information. While the increase (decrease) for the Conservative Party (UKIP) is highly significant, the

much small shifts for Labour, the Liberal Democrats and the Greens are not statistically different from 0.

All estimates are weighted using YouGov’s survey weights.

22

tion) while subsetting the analysis by respondents’ party identification. The resulting 25

estimates are presented in Table 8 and compactly visualized in Figure 6.

The results for the different party identifiers give rise to a more detailed picture. Focusing on respondents who identify with the Conservatives, we see that they are 13 percentage

points more likely to vote for the Conservatives in our experimental EU parliamentary

election when given an open-list ballot than when given a closed-list ballot, assuming the

provision of endorsements (p < 0.00, two-tailed test). Similarly, the same group of Tory

identifiers is 15 percentage points less likely to vote for UKIP (p < 0.000, two-tailed

test). Again, we find pretty much a mirror image for respondents who identify with UKIP:

they are 11 percentage points more likely to vote for the Conservatives under open-list

(p < 0.00, two-tailed test) and, correspondingly, 8 percentage points less likely to vote

UKIP (p < 0.019, two-tailed test). Hence, it is worth noting that the increase in support for the Conservatives comes not only from Conservative identifiers who can now vote

for Eurosceptic candidates of their preferred party, but also (though to a lesser degree)24

from UKIP identifiers who would vote for specific Conservative candidates if they had the

chance to do so. Almost all other 21 regression estimates are small in substantive terms

and not significantly different from 0. The only exception is that Labour identifiers appear

to be marginally less likely to support UKIP, which is consistent with the idea that some

Eurosceptic Labour voters vote UKIP under closed lists but Labour under open lists.

Having established that most of the action takes place among Conservative and UKIP

voters, we now turn our focus on the interaction of ballot type and respondents’ position

on Europe for these two parties. Respondents’ stance on European integration is measured

using an 11-point question ranging from “strongly opposed to British membership of the

EU” (0) to “strongly support further British integration in the EU” (10).25 For the analysis,

we recode this item in three binary indicators: Anti EU for values between 0–3, Neutral

for values between 4–6, and Pro EU for values between 7–10. Figure 7 displays the results

24

The magnitude of the effect of ballot type on propensity to vote Conservative is similar for Conservative

and UKIP identifiers, but the number of Conservative identifiers is much larger (33% vs. 12%).

25

This question was administered prior to assigning respondents to the different treatment conditions.

23

Figure 6: Effects of change from closed-list to open-list ballots, by respondents’ party

identification

GRN identifiers:

GRN voting GRN

●

GRN voting LAB

●

GRN voting LD

●

GRN voting CON

●

GRN voting UKIP

●

LAB identifiers:

LAB voting GRN

●

LAB voting LAB

●

LAB voting LD

●

LAB voting CON

●

LAB voting UKIP

●

LD identifiers:

LD voting GRN

●

LD voting LAB

●

LD voting LD

●

LD voting CON

●

LD voting UKIP

●

CON identifiers:

CON voting GRN

●

CON voting LAB

●

CON voting LD

●

CON voting CON

●

CON voting UKIP

●

UKIP identifiers:

UKIP voting GRN

●

UKIP voting LAB

●

UKIP voting LD

●

UKIP voting CON

●

UKIP voting UKIP

●

−0.2

−0.1

0.0

0.1

0.2

Effect of change from closed list to open list

Note: Changes in party vote shares when moving from closed-list to open-list ballots, given endorsement

information. Point estimates and 95 % confidence intervals from 25 separate OLS regressions for each party

vote share and each subsample of respondents identifying with one of the five main parties. All estimates

are weighted using YouGov’s survey weights.

24

from separate OLS regressions for the three groups Anti EU, Neutral, and Pro EU

for the Conservative party and UKIP, respectively.

The pattern that emerges could not be clearer: Respondents who support a further

integration of Britain in the EU26 do not change their voting behaviour depending on the

ballot type at all, and the effect among respondents who are neutral is small and not

significant. However, among Eurosceptic respondents—about 45 % of all Conservative

voters and 77 % of all UKIP voters—the shift from closed-list to open-list has major

consequences: the vote share for the Conservatives increases by almost 13 percentage points

(p < 0.001, two-tailed test) and the vote share for UKIP decreases by more than 17

percentage points (p < 0.001, two-tailed test).

To summarize, the subsample analysis confirms that the shift in vote shares from UKIP

to the Conservative Party comes from Euroskeptic voters who identify with either the Conservatives or UKIP. This offers further support for our argument about policy differentiation

and ballot type.

V. Conclusion

Which parties win and lose when a closed-list PR system (such as the one Britain uses

to elect its MEPs) is changed to an open-list system? We used a simple framework to

show how ballot type can affect voters’ choices, and hence election outcomes, through a

process of “differential differentiation” – the adoption by some parties, under open-list

elections, of a variety of policy positions (especially on a secondary issue) in a way that

tends to undermine the support of parties that are more unified. We carried out a survey

experiment that showed how voters might respond to differential differentiation in the

case of U.K. elections to the European Parliament, where we argued that the major parties

would field candidates representing a diversity of viewpoints on European integration while

UKIP would remain solidly Eurosceptic. We conclude that, just as UKIP lost support from

the adoption of open lists in our experiment, niche parties (who mobilize on an issue that

26

Naturally, the fraction of respondents who vote UKIP and are pro-European is very small, only 4 %

of all UKIP voters in our sample. For more details see next section.

25

Figure 7: Effects of change from closed-list to open-list ballots, by respondents’ stance on

Europe

●

Effect of change from closed list to open list

0.1

●

0.0

●

●

●

● Conservative Party

● UK Independence Party

−0.1

●

−0.2

Pro EU

Neutral

Anti EU

Voters' stance on European integration

Note: Changes in party vote shares when moving from closed-list to open-list ballots, given endorsement

information. Point estimates and 95 % confidence intervals from OLS regressions for the Conservative

and UKIP vote share, separately estimated for pro-European, neutral, and Eurosceptic respondents. All

estimates are weighted using YouGov’s survey weights.

26

cross-cuts the main dimension of party competition) would likely lose support from the

adoption of open lists in a broader set of circumstances.

It should be noted that our experiment can only really test part of the predicted effects

of a move from closed-list to open-list PR. That is, our results suggest that, conditional on

there being differential differentiation among the parties, the party that differentiates less

loses support (and the ideologically proximate party that differentiates more wins support).

Our experiment could not, of course, test whether the parties would actually respond in this

way to the introduction of open-list elections. While our experiment highlights the electoral

advantages of fielding a set of candidates with diverse views, those advantages are offset by

the possible damage such diversity might inflict on a party’s brand (Cox and McCubbins,

1993, 2005). Introducing a heterogeneous list of candidates may entail greater costs to the

party brand than the benefits gained by poaching the votes of undifferentiated parties. We

hope that future work can provide a more complete picture of how much the introduction

of open lists induces policy differentiation among candidates and how this differentiation

is likely to differ across parties; such work is necessary to get a clearer picture of who wins

and loses in a setting where party strategy and voter behavior jointly respond to a change

in ballot type.

One of the contributions of this paper is to broaden the range of issues that are relevant for intra-party competition in open-list system, and to show how these issues affect

inter-party competition. Previous work has focused on “valence” issues such as experience,

localness, and ability to distribute pork, all of which are thought to be important in determining which candidates win seats. We have emphasized the possibility that candidates

might compete on policy as well. Although differences in valence could affect relative party

success in an open-list system (Tavits, 2009), we suspect that differences in the extent to

which candidates on a single list adopt distinct policy positions (or “differential differentiation”) will in many circumstances be a more influential determinant of party electoral

strength, given that parties differ in their ability or willingness to allow for disagreement

on salient issues.

27

References

Adams, James, Michael Clark, Lawrence Ezrow and Garrett Glasgow. 2006. “Are Niche

Parties Fundamentally Different from Mainstream Parties? The Causes and the Electoral

Consequences of Western European Parties’ Policy Shifts, 1976-1998.” American Journal

of Political Science 50(3):513 – 529.

Ames, Barry. 1995a. “Electoral rules, constituency pressures, and pork barrel: bases of

voting in the Brazilian Congress.” Journal of Politics 57(2):324–343.

Ames, Barry. 1995b. “Electoral Strategy under Open-List Proportional Representation.”

American Journal of Political Science 39(2):406 – 433.

Ashworth, Scott and Ethan Bueno de Mesquita. 2006. “Delivering the Goods: Legislative

Particularism in Different Electoral and Institutional Settings.” The Journal of Politics

68(1):168 – 179.

Bakker, Ryan, Catherine de Vries, Erica Edwards, Liesbet Hooghe, Seth Jolly, Gary Marks,

Jonathan Polk, Jan Rovny, Marco Steenbergen and Milada Anna Vachudova. 2012. “Measuring party positions in Europe: The Chapel Hill expert survey trend file, 199:2010.”

Party Politics pp. 1 – 15.

Bräuninger, Thomas, Martin Brunner and Thomas Däubler. 2012. “Personal vote-seeking

in flexible list systems: How electoral incentives shape Belgian MPs’ bill initiation behaviour.” European Journal of Political Research 51:607 – 645.

Cain, Bruce E., John A. Ferejohn and Morris P. Fiorina. 1987. The Personal Vote. Harvard

University Press.

Carey, John M and Matthew Soberg Shugart. 1995. “Incentives to cultivate a personal

vote: A rank ordering of electoral formulas.” Electoral studies 14(4):417–439.

Chang, Eric CC. 2005. “Electoral Incentives for Political Corruption under Open-List

Proportional Representation.” The Journal of Politics 67(3):716 – 730.

Chang, Eric CC and Miriam A Golden. 2007. “Electoral systems, district magnitude and

corruption.” Journal of Political Science 37(1):115–37.

Commission, European. 2013. “Eurobarometer 74.3: The European Parliament, Energy

Supply, Data Protection and Electronic Identity, Chemical Labeling and Rare Diseases,

November-December 2010.”.

URL: http://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR34264.v3

Cox, Gary W. and Mathew D. McCubbins. 2005. Setting the Agenda: Responsible Party

Government in the U.S. House of Representatives. Cambirdge University Press, Cambridge.

28

Cox, Gary W and Mathew Daniel McCubbins. 1993. Legislative Leviathan: Party Government in the House. Vol. 23 Univ of California Press.

Crisp, Brian F., Maria C. Escobar-Lemmon, Bradford S. Jones, Mark P. Jones and

Michelle M. Taylor-Robinson. 2004. “Vote-Seeking Incentives and Legislative Representation in Six Presidential Democracies.” The Journal of Politics 66(3):823 – 846.

Duff, Andrew, ed. 2011. Report on a proposal for a modification of the Act concerning the

election of the Members of the European Parliament by direct universal suffrage of 20

September 1976. Number 2009/2134(INI) European Parliament.

Eggers, Andrew C. Forthcoming. “Proportionality and Turnout: Evidence From French

Municipalities.” Comparative Political Studies .

Ezrow, Lawrence. 2008. “Research Note: On the inverse relationship between votes and

proximity for niche parties.” European Journal of Political Research 47(2):206 – 220.

Ferrara, Federico and J. Timo Weishaupt. 2004. “Get your Act Together: Party Performance in European Parliament Elections.” European Union Politics 5(3):283–306.

Ford, Robert, Matthew J Goodwin and David Cutts. 2012. “Strategic Eurosceptics and

polite xenophobes: support for the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) in the

2009 European Parliament elections.” European Journal of Political Research 51(2):204–

234.

Geddes, Andrew. 2003. The politics of migration and immigration in Europe. Sage.

Grimmer, Justin, Solomon Messing and Sean J. Westwood. 2012. “How Words and Money

Cultivate a Personal Vote: The Effect of Legislator Credit Claiming on Constituent

Credit Allocation.” American Political Science Review 106(4):703 – 719.

Grofman, Bernard. 2004. “Downs and two-party convergence.” Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci.

7:25–46.

Hallerberg, Mark and Patrik Marier. 2004. “Executive Authority, the Personal Vote, and

Budget Discipline in Latin American and Caribbean Countries.” American Journal of

Political Science 48(3):571 – 587.

Hobolt, Sara B., Jae-Jae Spoon and James Tilley. 2009. “A Vote Against Europe? Explaining Defection at the 1999 and 2004 European Parliament Elections.” British Journal of

Political Science 39(01):93 – 115.

Hobolt, Sara B. and Jill Wittrock. 2011. “The second-order election model revisited: An

experimental test of vote choices in European Parliament elections.” Electoral Studies

30:29 – 40.

29

Meguid, Bonnie M. 2005. “Competition between Unequals: The Role of Mainstream Party

Strategy in Niche Party Success.” American Political Science Review 99(3):347 – 359.

Myatt, David P. 2007. “On the theory of strategic voting.” The Review of Economic Studies

74(1):255–281.

Samuels, David J. 1999. “Incentives to Cultivate a Party Vote in Candidate-Centric Electoral Systems: Evidence From Brazil.” Comparative Political Studies 32(4):487 – 518.

Shugart, Matthew Søberg, Melody Ellis Valdini and Kati Suominen. 2005. “Looking for

Locals: Voter Information Demands and Personal Vote-Earning Attributes of Legislators

under Proportional Representation.” American Journal of Political Science 49(2):437–

449.

Tavits, Margit. 2009. “Effect of Local Ties on Electoral Success and Parliamentary Behaviour: The Case of Estonia.” Party Politics 16(2):215 – 235.

UK Polling Report. 2014. “UK Polling Report.”.

URL: http://ukpollingreport.co.uk/european-elections

Wagner, Markus. Forthcoming. “Defining and measuring niche parties.” Party Politics

pp. 1–31.

30

VI. Figures

Figure 8: Print screen from closed-list without candidate information treatment

31

Figure 9: Print screen from closed-list with candidate information treatment

32

Figure 10: Print screen from open-list without candidate information treatment

33

Figure 11: Print screen from open-list with candidate information treatment

34

Figure 12: Quantile-quantile plot of empirical distribution of p-values against uniform

1.0

Empricial distribution of p−values against uniform distribution

Con Vote 2010

Lib Vote 2010

Con Party ID 2010

Lab Vote 2010

Region: Scotland

0.8

Lab Party ID 2010

No Party ID 2010

EU membership

Region: East

0.6

No Vote 2010

UKIP Party ID 2010

p−values

Region: South

Region: Midlands

Age

Region: Wales

0.4

Lib Party ID 2010

Green Party ID 2010

UKIP Vote 2010

Green Vote 2010

0.2

Region: London

Female

0.0

Region: North

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

Uniform distribution

Note: The quantile-quantile plot shows the empirical distribution of the p-values calculated from a joint

F –test of no differences between the 22 covariate means against the theoretically expected uniform distribution. All p-values are above the 45 degree line indicating that randomization was successfully implemented.

All estimates are weighted using YouGov’s survey weights.

35

Figure 13: Party vote shares in each of the four treatment conditions

0.30

●

●

●

●

Party vote shares

0.25

● Labour Party

UK Independence Party

Conservative Party

0.20

Green Party

Liberal Democrats

0.15

0.10

Closed list, no info

Open list, no info

Closed list with info

Open list with info

Note: The only significant differences in party vote share across treatment conditions are for the Conservatives and UKIP between the open-list with information condition, and the other conditions. This

indicates that neither the provision of information nor open lists on their own affect party vote choice.

36

VII. Tables

Table 3: MEP voting defections from national parties under different list-systems

(1)

Defection

Open-List

0.143∗∗∗

(0.012)

Party Size

0.085∗∗∗

(0.001)

Constant

−3.633∗∗∗

(0.012)

Observations

759,500

Note: Logistic regression coefficients shown with

corresponding standard errors in parentheses.

∗ p<0.1; ∗∗ p<0.05; ∗∗∗ p<0.01

Table 4: Internal party EU dissent/conflict

(1)

EU Dissent

−0.618∗∗∗

(0.236)

High-Salience

2.894∗∗∗

(0.105)

Constant

Observations

200

Note: Regression coefficients shown with corresponding standard errors in parentheses. ∗ p<0.1;

∗∗ p<0.05; ∗∗∗ p<0.01

37

Table 5: Vote shares of candidates and respondents’ stance on European integration

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

(5)

Vote shares of candidates by party

Party

GRN LAB LD CON

UKIP

Pro EU

0.48 0.48 0.55 0.26

0

Neutral

0.21 0.18 0.21 0.22

0

Anti EU

0.31 0.34 0.24 0.52

1

Observations 219

686 263

634

427

Party

Pro EU

Neutral

Anti EU

Observations

(6)

(7)

Respondents’

GRN LAB

0.40 0.37

0.39 0.39

0.21 0.25

219

686

(8)

(9)

(10)

self-placement by party

LD CON

UKIP

0.45 0.14

0.04

0.40 0.41

0.20

0.15 0.45

0.77

263

634

427

Note: Models 1–5 present the votes shares of pro-European, neutral and

Eurosceptic candidates by party under open-list with information. Models 6–10 present the shares of survey respondents that are pro-European,

neutral and Eurosceptic that identify with a particular party. All estimates are weighted using YouGov’s survey weights.

38

Table 6: Balance tests over covariate means

Covariates

Closed / No

EU membership

4.358

Female

0.489

Age

46.49

Lab Party ID 2010

0.333

Con Party ID 2010

0.281

Lib Party ID 2010

0.108

Green Party ID 2010

0.002

UKIP Party ID 2010

0.008

No Party ID 2010

0.210

Lab Vote 2010

0.256

Con Vote 2010

0.294

Lib Vote 2010

0.214

Green Vote 2010

0.005

UKIP Vote 2010

0.012

No Vote 2010

0.156

Region: North

0.239

Region: Midlands

0.169

Region: East

0.098

Region: London

0.132

Region: South

0.226

Region: Wales

0.047

Region: Scotland

0.088

Sample Size

2251.25

Closed / With

4.476

0.510

46.45

0.317

0.285

0.129

0.003

0.008

0.202

0.248

0.300

0.214

0.006

0.012

0.173

0.235

0.170

0.099

0.136

0.220

0.055

0.084

2259.53

Open / No

4.443

0.525

47.25

0.325

0.286

0.119

0.003

0.007

0.196

0.252

0.296

0.213

0.004

0.015

0.157

0.276

0.165

0.088

0.114

0.226

0.046

0.085

2346.71

Open / with p-value

4.377

0.679

0.533

0.102

46.77

0.569

0.327

0.830

0.290

0.972

0.120

0.462

0.003

0.411

0.008

0.624

0.194

0.746

0.246

0.932

0.295

0.990

0.216

0.996

0.009

0.311

0.018

0.324

0.155

0.610

0.233

0.027

0.152

0.550

0.099

0.660

0.130

0.252

0.241

0.572

0.053

0.579

0.091

0.888

2230.01

Note: Table reports means values in the four experimental treatments (“Closed / No” denotes closed list and no information provided on candidates’ positions on Europe; “Open / with” denotes open-list and information provided on

candidates’ positions on Europe) along with p-values corresponding to the test of the null hypothesis that the four means

are the same. All estimates, including the effective sample size, are weighted using YouGov’s survey weights.

39

Table 7: Main regression results of parties’ vote share by treatment conditions

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

(5)

GRN

LAB

LD

CON

UKIP

Outcome

Vote share Vote share Vote share Vote share Vote share

Open-list

-0.01

-0.00

-0.00

-0.00

0.02

(-1.18)

(-0.03)

(-0.33)

(-0.19)

(1.23)

With information

-0.00

0.00

0.00

-0.01

0.01

(-0.26)

(0.21)

(0.05)

(-0.71)

(0.62)

Open × information

-0.00

0.01

0.02

0.06

-0.09

(-0.09)

(0.24)

(1.30)

(2.70)

(-3.84)

Constant

0.12

0.30

0.10

0.24

0.25

(14.93)

(24.83)

(12.30)

(20.30)

(21.55)

Observations

9087.5

9087.5

9087.5

9087.5

9087.5

Note: Separate OLS regressions for models (1)–(5). Regression coefficients shown with corresponding t-statistic

in parentheses. All regressions are weighted using YouGov’s survey weights.

40

41

(2)

CON

GRN

-0.00

(-0.22)

0.01

(0.93)

-0.00

(-0.11)

0.02

(3.35)

2251

(15)

LAB

UKIP

0.01

(0.74)

0.01

(0.50)

-0.05

(-1.92)

0.08

(6.21)

2751

(1)

CON

CON

-0.01

(-0.29)

-0.06

(-1.72)

0.14

(3.00)

0.75

(31.10)

2251

(14)

LAB

LD

-0.00

(-0.06)

0.00

(0.30)

-0.00

(-0.30)

0.02

(3.00)

2751

(16)

LD

CON

0.03

(1.16)

0.05

(1.33)

-0.04

(-0.72)

0.03

(1.88)

717

(3)

CON

LAB

0.00

(1.70)

0.00

(1.33)

0.00

(0.32)

0.00

(0.00)

2251

(17)

LD

GRN

-0.03

(-0.58)

-0.03

(-0.83)

-0.02

(-0.26)

0.13

(4.64)

717

(4)

CON

LD

-0.02

(-2.07)

-0.01

(-1.23)

0.04

(2.78)

0.03

(2.80)

2251

(18)

LD

LAB

0.02

(0.77)

-0.02

(-1.00)

0.01

(0.13)

0.03

(2.10)

717

(5)

CON

UKIP

0.03

(1.00)

0.06

(1.82)

-0.18

(-4.30)

0.20

(9.14)

2251

(19)

LD

LD

-0.04

(-0.66)

-0.03

(-0.56)

0.05

(0.56)

0.76

(20.13)

717

(6)

GRN

CON

-0.02

(-0.45)

-0.03

(-1.02)

0.07

(1.48)

0.03

(1.02)

170

(20)

LD

UKIP

0.01

(0.39)

0.03

(0.90)

-0.00

(-0.01)

0.04

(2.30)

717

(7)

GRN

GRN

0.10

(1.58)

-0.01

(-0.14)

-0.06

(-0.58)

0.85

(15.68)

170

(21)

UKIP

CON

0.00

(0.26)

-0.00

(-0.70)

0.11

(3.94)

0.01

(1.41)

833

(8)

GRN

LAB

-0.02

(-1.40)

0.10

(1.58)

-0.06

(-0.89)

0.02

(1.40)

170

(22)

UKIP

GRN

0.00

(0.84)

0.01

(1.65)

-0.01

(-1.49)

0.00

(1.00)

833

(9)

GRN

LD

-0.07

(-1.62)

-0.08

(-1.99)

0.07

(1.63)

0.09

(2.06)

170

(23)

UKIP

LAB

-0.02

(-1.29)

-0.00

(-0.26)

0.01

(0.41)

0.02

(1.65)

833

(10)

GRN

UKIP

0.01

(0.48)

0.03

(0.96)

-0.02

(-0.32)

0.01

(1.15)

170

(24)

UKIP

LD

0.00

(0.16)

0.01

(0.55)

-0.02

(-0.67)

0.01

(1.01)

833

(11)

LAB

CON

0.00

(0.70)

0.02

(2.03)

0.00

(0.09)

0.01

(2.09)

2751

(25)

UKIP

UKIP

0.01

(0.32)

-0.01

(-0.54)

-0.08

(-2.10)

0.96

(53.29)

833

(12)

LAB

GRN

-0.02

(-1.13)

0.00

(0.03)

0.01

(0.41)

0.08

(7.10)

2751

(13)

LAB

LAB

-0.00

(-0.04)

-0.04

(-1.31)

0.04

(1.17)

0.80

(43.82)

2751

Note: Separate OLS regressions for models 1–25. Regression coefficients shown with corresponding t-statistic in parentheses. All regressions are weighted using YouGov’s

survey weights.

Observations

Constant

Open × information

With information

Voters’ party ID

Party vote share

Open-list

Observations

Constant

Open × information

With information

Voters’ party ID

Party vote share

Open-list

Table 8: Party vote shares by treatment, subset by voters’ party identification

VIII. Strategic voting, ballot type, and party choice in theory and

practice

The theoretical discussion in the paper is based on expressive voters, but similar points about the possible

effect of ballot type on party vote choice can be made based on strategic voting. A strategic voter decides

how to vote based on the policy outcomes she expects from each possible vote she could cast. If ballot type

is to make any difference to a strategic voter’s vote choice, it must be that the voter believes that individual

MEPs have a non-negligible effect on policy outcomes, whether because MEPs do not simply follow the

party line or because MEPs help to create the party line. If that is the case, then ballot type can affect a

strategic voter’s party vote when it changes the “pivotal event” (Myatt, 2007) associated with the highest

expected utility differential for that voter. Consider, for example, a strategic Eurosceptic voter whose

utility is simply increasing in the number of Eurosceptic MEPs elected. Under closed lists, this voter must