ABIM Statement in Response to April 7 Newsweek Opinion Column

advertisement

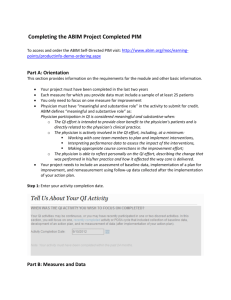

ABIM Statement in Response to April 7 Newsweek Opinion Column Philadelphia, PA, April 8, 2015 – On April 7, 2015, Newsweek posted an opinion column containing incorrect information about the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM). ABIM Accounting Information The opinion column inaccurately suggests that ABIM's decision to offer a new program with new payment options in 2014 was driven by financial considerations and also mischaracterizes ABIM's financial position. ABIM has always maintained a sufficient cash balance to meet the future commitments made to more than 90,000 diplomates who have paid “up front” and enrolled in its program for 10 years, and ABIM's accounting accurately reflects these future obligations. ABIM's financial information is independently audited each year by one of the nation's most-respected accounting firms. The most recent report, available on ABIM's website, resulted in an “unqualified opinion.” According to Generally Accepted Accounting Principles, the auditor “has the responsibility to evaluate whether there is substantial doubt about the entity's ability to continue as a going concern for a reasonable period of time” – if such doubt existed, they could not issue an unqualified opinion. Efforts to Reduce Duplicative Reporting In furtherance of its tax exempt purposes, ABIM is proud of its efforts to ensure that physicians meet high quality standards while simultaneously minimizing overly burdensome and duplicative reporting requirements. ABIM has been very supportive of public policies that enable physicians who participate in Maintenance of Certification (MOC) to fulfill other reporting requirements. ABIM has been transparent about these efforts and complies with the Internal Revenue Code and Internal Revenue Service rules applicable to organizations that are exempt from tax under Internal Revenue Code Section 501(c)(3), including the rules regarding lobbying activities by such organizations. Moving Forward On February 3, 2015, ABIM announced changes in its MOC program and a commitment to actively engage with the internal medicine community. Together, we will seek the best ways to fulfill our shared responsibility to be prepared to meet our patients' needs in a rapidly changing environment. We are in the early stages of those conversations and look forward to continued dialogue with the community we serve to create meaningful programs. For media inquiries, contact press@abim.org. About ABIM For more than 75 years, certification by the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) has stood for the highest standard in internal medicine and its 20 subspecialties and has meant that internists have demonstrated – to their peers and to the public – that they have the clinical judgment, skills and attitudes essential for the delivery of excellent patient care. ABIM is not a membership society, but a non-profit, independent evaluation organization. Our accountability is both to the profession of medicine and to the public. ABIM is a member of the American Board of Medical Specialties. For additional updates, follow ABIM on Facebook and Twitter. MOC Watch: ABMS President Rebuts Critics Though MOC needs improvement, it remains valuable to physicians. • • by Shara Yurkiewicz MD Staff Writer, MedPage Today Criticism against maintenance of certification (MOC) has been mounting since the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) adopted the new requirements in early 2014. Though the ABIM promised major changes earlier this year, the organization -- as well as its parent organization, the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) -- has continued to come under fire by physicians. Physicians have called the MOC process burdensome and irrelevant, and some have questioned the financial motives of the certifying boards. In January of this year, opponents of the ABMS program established the National Board of Physicians and Surgeons (NBPAS) to offer an alternative route for recertification in various specialties. Meanwhile, how is the ABMS responding to the criticism? MedPage Today talked to Lois Nora, MD, JD, MBA, president and chief executive officer of ABMS. "We are committed to improving MOC while underscoring its importance," Nora told MedPage Today during a phone call monitored by a communications officer from ABMS. Nora responded to criticisms leveled against ABMS, discussed steps the board is taking to address them, and explained why she so strongly believes in the importance of MOC. MedPage Today: Critics of MOC have argued that there are no independent studies (those that aren't board-funded) that show its effectiveness. What would you say to that? Nora: I'd say three things. First, board certification itself has been well demonstrated to be a quality indicator by a variety of research. Second, it's important to underscore that research done by the Boards on MOC is actually part of our quality improvement. While I understand people want to see research in addition to that, it's exceptionally important that we do our own quality investigation and report it publicly. So I am proud of the specialty board research that has been done on MOC. Third, with regard to outside research on MOC, it's important first of all to understand that the structure of the MOC program is constructed and based on research that has been done in quality science, adult learning, and assessment. So it is an evidence-based program in terms of how it is constructed. Because it is a young program, there is still less research than all of us would like to have on MOC. But there is emerging research ... that has demonstrated that MOC makes a difference in terms of patient outcome. Much of that research is related to the quality improvement activities that physicians do as part of their MOC, but there is developing research underscoring value of MOC in terms of patient care. MPT: Another criticism that people have mentioned is that the MOC exams aren't always relevant to everyday practice. The example often used is that of anesthesiologists who care for adult patients -- why would they need to memorize pediatric dosing? Also with regard to relevance, critics have said that some of the quality improvement [QI] projects aren't always clinically relevant or useful. Nora: Sure. I'll talk about MOC as a whole and then specifically about the exam and then the QI projects. MOC is an integrated program of multiple elements. It's important that it cover breadth of the specialty as well as the specifics in which a physician is engaged. A good example is that many pediatricians in this country have never seen a case of measles. Very few pediatricians in fact will see a case of measles. But with the changes in immunization rates that we are seeing -- for example, in California -- it's important that pediatricians recognize and understand that particular illness. So elements of the integrated MOC program have to cover things that are both common and uncommon. In terms of the examinations: the examinations are developed not by a small group of people but actually by substantially large groups of people in the specialty. They make determinations of what is most appropriate on that exam. A number of the boards are moving towards more modular exams. So if someone has their practice focused in a specific area of a specialty, more of the exam will be focused on those topics. We're seeing that movement. But it's important to recognize that MOC as a whole integrates both the common and the uncommon, and the exam is increasingly becoming more modular and specific. But each board determines the appropriate balance. The QI projects in particular are where the new standards are making a substantial difference in a part of MOC that has some people pretty exercised. The QI projects are related to our part of MOC that is called Improvement in Medical Practice. The new standards state ... that the physician diplomate should be engaged in quality improvement activities either in his or her practice or in the health system in which that person practices. We think most physicians are, in this day and age, engaged in these quality improvement activities, oftentimes very explicitly and knowingly. Most physicians do this within their practice anyway. When MOC began, there was a lot less attention to quality improvement activities; they were less prevalent. I believe early in MOC there was the development of practice improvement modules, but there were not enough to cover the breadth of specialties. A number of physicians felt that they were being asked to do something that was not relevant to their everyday practice. The new standards recognize the current situation with many more quality improvement projects available through health systems, hospitals, and specialty societies and to physicians in smaller practices -- there are many more things available. And boards are recognizing and giving credit for those activities more now than they have done in the past. So it's the new standards that are enabling and encouraging the transition. I do believe that some physicians were frustrated by not finding the required modules relevant and recognizing that they were doing QI themselves in their health systems. MOC will better recognize the quality improvement activities that physicians are doing. MPT: Critics have argued that the ABIM [American Board of Internal Medicine] pass rates are declining. The ABIM has rebutted that claim. With regard to specialty boards, what are the pass rates like? Are they declining? And if so, is there a reason you think is behind it? Nora: I can give you the broad view across specialties. In general, pass rates for both initial certifications and for maintenance of certification examinations do have some change from year to year, but overall they remain constant. In addition, perhaps not surprisingly, pass rates for the maintenance of certification examinations tend to be higher than the pass rate on the initial board certification examinations. MPT: Another complaint is that the financial burden of MOC is too high. That includes exams, study materials, taking time away from practicing. Nora: Physicians spend time on continuing education as a matter of course. For example, many of us go to specialty society meetings, have continuing education courses that we pay for, and the like. Many of those things, if not all, tend to count for maintenance of certification, as well. So I am not sure of the specific additive costs that people are talking about when referring to continuing education. I think where price sometimes becomes an issue is around the exam. I just took my exam in February. I tried to keep track of this for myself, and I think I probably did one or two more continuing education projects last year than I would have normally. That ups the cost by about $150. I did take an online exam prep course. That was another $1,000. These costs are spread over 10 years, and I'm not sure that is much of a burden. One of the things that many people find burdensome can be going away from home to take a course or going away to a test center. So we're hoping that more and more things are online.Various boards are working on ways to help make the exam a less stressful experience. Certainly, we also have to recognize that just taking an exam is a stressful experience in itself. I experienced that stress. I think part of what we're trying to do is first ask the question of what real additive burdens there are and then, secondly, to try and address any of those burdens in ways that we can to help make it less burdensome. Several of our boards are experimenting with remote proctoring that will save people a trip to an examination center. MPT: You've started to mention some ways in which the ABMS is responding to criticism from individuals and societies. What other ways are you doing so? Nora: I think very thoughtfully. Board certification and maintaining certification is an extremely important part of our professional self-regulation. When we reviewed maintenance of certification standards over a 2-year period, we solicited input from specialty societies, organized medical organizations (the AAMC, the AMA), and others that represent tens of thousands of physicians. We had an open comment place on our website, and we heard from hundreds of physicians about this. And we took that feedback very, very seriously. We want to make sure, out of a responsibility to the role of certification, professional self-regulation, and our responsibility to the public, that we have a continuing rigorous process. But we also want it to be meaningful and relevant for physicians. So we are listening carefully. Changes have been made. For example, many boards have always welcomed specialty relevant accredited continuing education activities from many providers. Some of our boards have been more restrictive about that, and those boards are becoming more flexible. Looking at the examination and ways that the examination can become a tool for physicians not only to assess the learning that they've done but to help them learn better, with better feedback to diplomates about how they did. And then looking at some ways to make the exam less stressful. Another major response we are taking that we talked about earlier in the conversation: looking at improvement in medical practice. We recognize that many things physicians are already doing are consistent with the standards, such as being involved in meaningful, relevant quality assessment and improvement activities in their practice and health system. These activities should be recognized and given appropriate credit. MPT: Are there any other changes to MOC in the near future that you can foresee? Nora: We viewed 2014 as an implementation year, and the 2015 standards have only been in place for a few months. Our boards are looking at all areas of improvement to make sure that board certification continues to be as meaningful to the public as it needs to be while being as relevant and valuable to physicians as it can be. MPT: Switching to two recent developments: first off, the establishment of an alternate certifying organization, the NBPAS [National Board of Physicians and Surgeons]. Would you like to comment? Nora: Alternative boards and the like have come up periodically over the years. I will note that the NBPAS actually underscores the value of board certification by an ABMS board in that it makes it a requirement. I'm more interested in talking about why our MOC program, while it needs to improve, still is the most appropriate way to recognize board certification and maintenance of certification. I believe that the ABMS member boards and [the NBPAS] board are fundamentally different organizations. MPT: There was also the second article written by Kurt Eichenwald in Newsweek about ABIM [specifically its financial practices]. Do you have any comments or response? Nora: It's an opinion piece. I don't share Mr. Eichenwald's opinion. You mentioned that it was very ABIM-focused, and so I think that is the organization to respond. MPT: Do you want to have the last word on anything? Nora: I will just share with you something that I'm not sure we've actually talked about as much as I think we need to. And that's how MOC can be of even more value to physicians during a time in which physicians are under tremendous stress. There are many things that make medical practice difficult right now: new regulations, the perceived loss of autonomy, and other things. I believe that maintenance of certification as a framework for demonstrating what physicians are doing is important for the public. A recent RAND study ... talked about satisfiers and dissatisfiers in physicians' practices. One of the satisfiers is when physicians feel enabled and empowered to improve the activities within their health system and within their practice. So from my perspective, that underscores the importance of improvement in medical activities that physicians do and that is recognized in MOC. Finally, in an era when we know that physicians are being employed to a larger degree, keeping board certification as an extraordinarily strong part of professional self-regulation and a meaningful and relevant credential is important. We are committed to improving MOC while underscoring its importance. A vocal group of doctors is thumping mad. Is your doctor one of them? Here's the backstory. If you live in Colorado, Indiana, Montana, New York or South Dakota, your doctor could be practicing for 30 years and never be required to keep up-to-date as a condition of renewing his or her medical license every few years. Just fill out a form and send a check. It's not much better if you live elsewhere. Other states require licensed doctors to do as little as 20 hours of self-study a year. To raise the standard in a high-stakes profession, most doctors choose to become certified by a board of their peers in their specialty, say family medicine or surgery. Maintaining this certification requires passing a knowledge exam every 10 years and demonstrating continuous learning and improvement in the care provided to patients. A group of doctors has circulated a petition to do away with independent examinations of doctors' medical knowledge and requirements to improve their practice, saying it is too burdensome and not relevant to what they do every day. Their solution? Continuing medical education, shorthand for no independent determination of whether a physician is keeping up-to-date. Taking a page from Hillary Clinton's "Trust me" attitude in deciding which emails should be made public from her private account while Secretary of State, the doctors' stance is a "Trust me" too. It doesn't fly. Here's why. First, the public wants to trust their doctor but also wants independent verification that their doctor meets a higher standard: "Trust, but verify." Second, if the certification process is not well-tailored to physician practice and too costly, don't throw it out, fix it. Make it relevant. Make it better. Test competence as well as knowledge. Here's an example. A University of Michigan study of physicians who perform bariatric surgery were videotaped while performing surgery. Their surgical skill was independently assessed by their peers who were unaware of who was performing the procedure. Not surprising, patients whose surgeons had better skills fared better. Independent assessment pinpoints where a physician's competence can be improved. Most people probably think this type of testing is already being done. It isn't. It should be. Raise the bar. Don't lower the floor. Third, the public expects that doctors stay abreast of emerging health threats such as antibioticresistant superbugs and how to diagnose and treat them. A gentleman I know in the Washington, D.C. area who had surgery noticed that the wound had become red and swollen. His doctor did not follow the standard protocol developed by physicians that has reduced these infections. The result? Months of painful and costly treatment of an antibiotic-resistant infection. Doctors are like the rest of us. We don't know what we don't know. Fully free choice of continuing education is not a solution. Take patient safety. Most doctors never learned patient safety in medical school. It was never taught, although that it beginning to change. Fortunately, future doctors in training are expected to learn how to identify common medical errors and unsafe situations, and how to reduce the chance of patient harm. Physicians in 2015 should not practice cardiology or surgery as if it were the 1990s. Nor should they practice as if it were the 1990s when it comes to safety. A cadre of dedicated physicians have been learning and applying safety science in patient care -on top of their heavy workloads -- with promising results. To bring more practicing doctors up to speed, the certification process has given greater emphasis to patient safety. Remarkably, opponents of certification have characterized patient safety as "busy work" in an article in the well-known New England Journal of Medicine. There is a saying among professionals who go to work every day to ensure public safety whether on airplanes, in space flight, in nuclear power plants, on America's highways or in the doctor's office or hospital: anyone who is not trained to see how mistakes can happen, nor equipped to avoid them, is the most dangerous person in the room. The public has the biggest stake in the outcome of whether physicians should be expected to have independent assessment of their knowledge and performance in practice. We have been left out of the debate. The media should invite the public into the dialogue. Hopefully it will be without some of the vitriol that has surfaced. Perhaps it is indicative of physician burnout, fueled by unrealistic demands by their employers and insurance companies to see too many patients in too little time in a system filled with opportunities for error. Whatever the etiology, a constructive tone would be consistent with the professionalism the public expects. In the interest of full disclosure, three years ago I agreed to be an unpaid, independent public member of the public policy committee of the American Board of Medical Specialties. It works in collaboration with the 24 specialty boards that offer certification to physicians. My purpose has been to encourage patient safety as an integral part of ongoing assessment of physicians, an interest sparked 15 years ago while writing Wall of Silence, the first book to tell the human story behind the Institute of Medicine report, To Err is Human. Recent estimates suggest that more than 400,000 Americans die from preventable health care harm annually. All hands on deck are needed to stem the mayhem. The patient on the gurney is counting on it. "Trust me" doesn't work. Rosemary Gibson is the author of Wall of Silence and is the 2014 recipient of the American Medical Writers Association award for her writing on health care in the public interest. She is a founding member of the Consumers Union Safe Patient Network and is senior advisor at The Hastings Center. www.rosemarygibson.org Follow Rosemary Gibson on Twitter: www.twitter.com Updated | Are physicians in the United States getting dumber? That is what one of the most powerful medical boards is suggesting, according to its critics. And, depending on the answer, tens of millions of dollars funneled annually to this non-profit organization are at stake. The provocative question is a rhetorical weapon in a bizarre war, one that could transform medicine for years. On one side is the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM), which certifies that doctors have met nationally recognized standards, and has been advocating for more testing of physicians. On the other side are tens of thousands of internists, cardiologists, kidney specialists and the like who say the ABIM has forced them to do busywork that serves no purpose other than to fatten the board’s bloated coffers. “We don’t want to do meaningless work and we don’t want to pay fees that are unreasonable and we don’t want to line the pockets of administrators,’’ says Dr. Paul Teirstein, a nationally prominent physician who is chief of cardiology at Scripps Clinic and who is now leading the doctor revolt. Try Newsweek for only $1.25 per week The physicians lining up with Teirstein are not a bunch of stumblebums afraid of a few tests. They include some of this nation’s best-known medical practitioners and academicians, from institutions like the Mayo Clinic, Harvard Medical School, Columbia Medical School and other powerhouses in the field. This spat is hardly academic, though. Some doctors are leaving medicine because they believe the ABIM is abusing its monopoly for money, forcing physicians to unnecessarily sacrifice time with their patients and time for their personal lives. A little history: For decades, doctors took one exam, usually just after finishing training, to prove they had absorbed enough medical knowledge to treat patients. Internists—best known as primary care physicians—would take one test while those who chose subspecialties of internal medicine—cardiovascular disease, critical care, infectious disease, rheumatology—sat for additional exams. Doctors maintained their certification status by participating in programs known as “continuing medical education,” which, when done right, keep physicians up on developments in their field. The value to a doctor of being certified can scarcely be overstated. Many organizations will not hire uncertified doctors. And, without that stamp of approval, even doctors who open their own practices rarely receive permission from hospital boards to treat their patients in hospitals. It was a sensible way to make sure doctors stayed on top of their game and weed out incompetent clinicians. Someone, of course, had to pay for the testing and continuing education, and it was usually the doctors. So physicians shelled out money to the ABIM to take the tests, and then ponied up more cash to attend conferences and other programs for continuing medical education. Few objected—it was worth the money to keep up the profession’s standards. But then ABIM decided that rather than just having doctors take one certification test, maybe they should take two. Or three. Or more. Under this new rule adopted in the early 1990s, internists and subspecialists recertify every 10 years with new tests. In other words, a doctor certified at the age of 30 could look forward to taking an ABIM exam at least three more times before retirement. This was not cheap—doctors spend thousands of dollars not only for the tests, but for review sessions, for time away from their practices. And with each new test, the ABIM made more money. Physicians sheepishly went along with the process, assuming their good old pal the ABIM was working hard to make sure medical practitioners were fully qualified. Then, something strange happened, doctors say. The tests started including questions about problems that had nothing to do with how doctors did their jobs. For example, endocrinologists who worked exclusively with adults said they were forced to answer questions about endocrinology for children, even though the pediatric information was irrelevant to their practices. Heart specialists who do not perform transplants – and even those at hospitals with no heart transplant programs – said they had to study techniques for reading transplant tissue slides and how best to evaluate these patients so they could answer questions on the tests. But that knowledge was unrelated to the care they provide to their real patients, they said, and took time that they could have spent learning the latest medical findings about the cardiology work they actually perform.Videos and study sessions sold to help doctors prepare for re-certification exams often featured instructors saying physicians would never see a particular condition or use a certain diagnostic technique, but they needed to review it because it would be on the test. “Exam questions often are not relevant to physicians’ practice,” Teirstein says. “The questions are often out-dated. Most of the studying is done to learn the best answer for the test, which is very often not the current best practice.” The result? According to the ABIM’S figures, the percentage of doctors passing the recertification test started dropping steadily. In 2010, some 88 percent of internists taking the maintenance of certification exams passed; by 2014, that had fallen to 80 percent. Hematologists dropped from 91 percnet to 82 percent. Interventional cardiologists went from 94 percent to 88 percent. Kidney specialists, 95 percent to 84 percent. Lung experts, 90 percent to 79 percent. • MOST SHARED • A Certified Medical Controversy Shares: 19k • Thousands of Turkish Students Demand Jedi Temples On Campus Shares: 17.5k • Opie and Anthony No More: Inside the Nasty Breakup of Radio's Most Notorious Shock Jocks Shares: 5.2k • Report: Russians Hacked White House Shares: 3.2k • In Orthodox Jewish Divorce, Men Hold All the Cards Shares: 993 • MOST READ • Report: Russians Hacked White House • A Certified Medical Controversy • Opie and Anthony No More: Inside the Nasty Breakup of Radio's Most Notorious Shock Jocks • Thousands of Turkish Students Demand Jedi Temples On Campus • Three Former Wrestlers Sue WWE Wow. Was it Obamacare? Ebola? A sign of the end times? What was turning so many American doctors so stupid all of sudden? Not to worry, the ABIM declares—the board could help doctors keep their certification. All they had to do was pay to take the tests again. Making doctors appear ignorant became big business, worth millions of dollars, and the ABIM went from being a genial organization celebrated by the medical profession to something more akin to a protection racket. The ABIM disputes that characterization. Lorie B. Slass, a spokesperson for the ABIM, says “there have been and always will be” fluctuations in test results, since different groups of doctors are taking the exam each year. But in each of the categories cited above, there are no statistically significant fluctuations—the passing rate keeps going down. So the point remains: Either doctors are getting dumber each year, or the test that helps determine who gets to practice medicine has less and less to do with the actual practice of medicine. Slass says the suggestion that the ABIM is “purposefully failing candidates on their exams to generate more revenue is flat-out wrong.” Maybe so, but according to the Form 990s filed with the Internal Revenue Service, in 2001—just as the earliest round of new-test standard was kicking in—the ABIM brought in $16 million in revenue. Its total compensation for all of its top officers and directors was $1.3 million. The highest paid officer received about $230,000 a year. Two others made about $200,000, and the starting salary below that was less than $150,000. Printing was its largest contractor expense. That was followed by legal fees of $106,000. Twelve years later? ABIM is showering cash on its top executives—including some officers earning more than $400,000 a year. In the tax period ending June 2013—the latest data available—ABIM brought in $55 million in revenue. Its highest paid officer made more than $800,000 a year from ABIM and related ventures. The total pay for ABIM’s top officers quadrupled. Its largest contractor expense went to the same law firm it was using a decade earlier, but the amounts charged were 20 times more. And there is another organization called the ABIM Foundation that does...well, it’s not quite clear what it does. Its website reads like a lot of mumbo-jumbo. The Foundation conducts surveys on how “organizational leaders have advanced professionalism among practicing physicians.” And it is very proud of its “Choosing Wisely” program, an initiative “to help providers and patients engage in conversations to reduce overuse of tests and procedures,” with pamphlets, videos and other means. Doesn’t sound like much, until you crack open the 990s. This organization is loaded. In the tax year ended 2013, it brought in $20 million—not from contributions, not from selling a product, not for providing a service. No, the foundation earned $20 million on the $74 million in assets it holds. The foundation racked up $5.2 million in expenses, which—other than $245,000 it gave to the ABIM—was divided into two categories: compensation and “other.” Who is getting all this compensation? The very same people who are top earners at the ABIM. Deep in the filings, it says the foundation spends $1.9 million in “program and project expenses,” with no explanation what the programs and projects are. There are some expenditures, though, that are easy to understand: The foundation spends $153,439 a year on at least one condominium. And it picks up the tab so the spouse of the topofficer can fly along on business trips for free. The ABIM is not what it was. Its original mission was to make sure doctors provide patients with the best care. When condominiums and lavish salaries and free trips and making money off of physicians failing tests became a priority, the evidence suggests the organization lost its way. But that may not matter soon. In January 2014, when the ABIM issued a series of new requirements for maintaining certification— that would have generated all new fees—Teirstein and his colleagues declared “enough.” They recently formed a new recertification organization called the “National Board of Physicians and Surgeons.” It will only consider doctors for recertification who have passed the initial certification exam that has been required for decades. Doctors must also log a set number of hours with programs that qualify under guidelines as continuing medical education. The group’s fees are much, much lower than those charged by the ABIM. And its board and management—all top names in medicine—work for free. This new board is not just about breaking the ABIM monopoly, Teirstein says, but is also part of an effort to put the right people in charge of the profession’s future. Medicine has been “controlled by individuals who are not involved with the day to day care of patients,” he says. “It is time for practicing physicians to take back the leadership.” Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly suggested that ABIM also certifies anesthesiologists. Anesthesiologists are certified by the Board of Anesthesiology. A Certified Medical Controversy BY KURT EICHENWALD 4/7/15 My wife is an internist. My brother is a pediatrician at a major academic institution. So was my father. My best friend is a surgeon. I regularly see an internist for my medical care, and I like her very much. I also should mention that this article is an opinion column. And it is my opinion that the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) has hidden managerial incompetence for years while its officers showered themselves with cash despite their financial ineptitude and the untold damage they have inflicted on the health care system. That unnecessary first paragraph is necessary because ABIM apparently considers itself the enemy of doctors, since it believes a journalist with ties to physicians (me) must be biased against the organization. I found that out when I recently wrote about a group of nationally renowned physicians who revolted against the ABIM, which certifies doctors as meeting certain medical standards. The roots of the uprising trace to January 2014, when ABIM attempted to expand its program for recertifying doctors, adding boatloads of requirements and fees to be paid by physicians. As a result, the prominent group of doctors formed a competing certification organization, while condemning ABIM’s recertification program as an expensive waste of time that hasn’t been shown to improve medical knowledge or the quality of health care. In response, ABIM attacked me—claiming that since my wife is a doctor, I have a conflict of interest in reporting about an uprising by physicians—then defended itself with a series of misrepresentations and absurdities. Topping it off, they condemned Newsweek for allowing me to express an opinion in an opinion column. That told me either ABIM uses the same public relations firm employed by Scientology, or its officials have a lot more to hide. So I decided to dig deeper. The answer? Whoo-boy, does ABIM have a lot to hide. First, one clarifying preamble: While ABIM certifies about one out of every four doctors in America, it is not alone. Doctors with specialties unrelated to internal medicine are certified by other organizations—most of which are part of a larger body called the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS). While there is anger brewing among these specialists, who also feel abused and cheated, they aren’t fomenting a revolt like the one playing out with ABIM. So while there is plenty to say about the other certification boards, let’s stick with the group that has doctors attempting to organize a coup and why they are so unhappy. What I found suggests that the primary reason ABIM attempted to expand its recertification process—which set off the uprising—is that the organization has been crippled by accounting games and needs a lot more revenue, fast, to avoid a fiscal train wreck. I also found misleading or false statements in government filings, attempts to withhold public information, damage inflicted on federal science programs and more. ABIM now even appears to be trying to trick Congress into passing laws that would force doctors to cough up cash to cover the organization’s financial follies. It even benefited from something slipped into Obamacare that seems to have been written by ABIM or its lobbyists. The last sentence says “seems” because, other than saying it complied with the rules on filings with the government, ABIM ignored every question I asked it before writing this column. It wouldn’t even say “no comment.” Even though it’s supposed to be public information, ABIM also refused to provide the 2014 salary it paid ABIM President and CEO Rich Baron, perhaps the most Dickensian name since Dickens. (By the way, from what I’ve learned, Baron received $568,000 plus $135,000 in deferred compensation last year. ABIM will have to officially reveal those numbers in a filing to the government sometime in May.) Start with ABIM’s Form 990. This is the document a nonprofit organization has to file with the Internal Revenue Service to disclose its activities and prove it deserves tax-free status. In Part IV, which appears on Page 3 of the document, the government asks a simple question on line 4: “Did the organization engage in lobbying activities?” And year after year, ABIM has answered “no.” Unfortunately, the real world answer is “yes.” According to the Center for Responsive Politics, from 2009 through 2014, ABIM paid $390,000 to Mehlman Vogel Castagnetti, a lobbying firm. Asked about this, an ABIM representative says it complied with all rules governing IRS filings. Maybe. Yet according to Independent Sector, a prominent organization for nonprofits, the words “lobbying activities” in line 4 includes elements as miniscule as holding strategy meetings to coordinate lobbying with others and time spent preparing arguments to be advanced to government officials. Unless ABIM just wrote a check and never spoke to its lobbyists, it’s hard to see how it complied with those standards. (Side note: A random check of seven 501(c)(3)s that paid less than ABIM to lobbying firms showed all of them answered with a “yes” on line 4.) So what did ABIM spend all this lobbying money on? According to Mehlman Vogel’s filings with the government, ABIM’s lobbyists provided “strategic advice” on issues related to Obamacare, including “physician quality reporting requirements.” And if you haven’t guessed yet, what does the ABIM consider “physician quality reporting requirements”? Maintenance of certification (MOC), the program that so many doctors say is worthless—and that ABIM refuses to show has any impact on “physician quality” with independent research or other science-y stuff. Did the lobbying work? Yup. Under Obamacare, physicians who participated in MOC through 2014 qualified for an incentive payment. The description of MOC is so specific in the law that ABIM and similar groups in ABMS were the only organizations that met the definitions. In other words, in the first few years of Obamacare, the government was paying doctors to pay ABIM and related certification organizations to participate in a program that has never been proven to do squat. And now it looks like the government may have been lobbied to create more pressure on physicians to shell out cash to ABIM and its brethren. This time, it’s through a bill just passed by the House called the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act. Among its provisions is one where doctors would qualify for a new incentive pay system in Medicare by meeting quality standards established by the government in consultation with certification boards like ABIM. Unless these groups finally acknowledge that MOC programs have not been independently demonstrated to improve patient care, doctors could be subjected to federal coercion to participate in them—and pay the boards more fees—whether they want to or not. Unfortunately, there are bigger problems with MOC programs than forcing doctors to spend time and money on something that has never been proven to have any value. Instead, they are harming medicine. A recent report by the National Institutes of Health concluded that, with subspecialty board recertifications becoming more time-consuming, many physician-scientists are refusing to go through the process, choosing instead to drop their hospital privileges and end their work in clinics. The report concluded that this “can have a profound effect on the quality of care delivered by large numbers of more general subspecialty physicians who seek their advice and refer patients for consultation.” In other words, not only have certification organizations failed to prove MOC provides any benefit, but scientific experts also say it is damaging the quality of care. To understand why ABIM is pushing so hard on the MOC you need only look at its accounting. Those numbers say ABIM is in danger of becoming a financial corpse. “It is just shocking,’’ Charles P. Kroll, a certified public accountant who specializes in health care, says of the consolidated financial statements of ABIM and a related entity, the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation. “I have never seen anything like it in my 35 years of accounting and auditing experience.” Kroll says he has no vested interest in his ongoing investigation of ABIM’s finances and has taken on the organization largely out of outrage at what he considers to be its accounting abuses. ABIM made it quite difficult to obtain its audited financials, he says, but the group eventually posted one year’s version on its website. By then, however, Kroll had obtained copies elsewhere and found that ABIM, in that posting, left out many pages without revealing it had done so, a move that hid plenty of its expenses—including salaries—from prying eyes. Kroll disclosed the ruse online and ABIM quietly reposted the document, this time in full. What it showed were accounting techniques that would make the illusionists at Enron blush. ABIM and the ABIM Foundation lost $39.8 million on program services in the five years ended 2013—a nonprofit indeed. Yet during that same time, the organizations paid $125.7 million to its senior officers and staff. How does any organization with year after year of massive losses continue paying huge salaries? By relying on an accounting maneuver called “deferred revenue.” Until January 2014, ABIM maintained a 10-year MOC program, in which doctors coughed up a series of fees. But the payments came before the doctors went through the decade-long process of recertifying, so ABIM counted the money as a liability—revenue it had received for services not yet provided. In other words, in extremely simplistic terms, ABIM was taking advances from doctors for a board recertification owed sometime in the future. And that deferred revenue grew to the point where it reached $94 million as of June 30, 2014. The huge sums of cash were only recognized as revenue when the various services—like a test—were provided. And there is the bookkeeping magic trick. ABIM is collecting a lot of money up front that it is not recognizing on its income statement and then using the cash to fund the massive losses from the program itself. “Deferred revenue has kept them afloat,’’ Kroll says. “They are in a financial free fall. I have never seen anything so reckless.” What throws the financial train off the track, unsurprisingly, is lavish spending. Millions have been paid out to senior officers of ABIM, with additional amounts stuffed away in an obscure line in its 990s for “deferred compensation.” Meanwhile, ABIM’s net assets minus liabilities were negative$47.9 million on June 30, 2014; staff expenses for the fiscal year ended that same day climbed 13 percent, or $3.5 million, to $30.7 million. There were forehead-slapping losses too: ABIM purchased $3.6 million in computer equipment in fiscal 2013, then wrote it all off in 2014, proclaiming in a footnote in its financials that the technologies were “no longer suitable for their intended use.” Which brings us back to the beginning: ABIM’s announcement in January 2014 that it was changing the MOC process into something so onerous and expensive that it set off a doctor rebellion. Footnotes in the audited financials make one thing clear: The MOC revision, which ABIM says it will abandon and revise in the face of the uproar, had nothing to do with improving medical education. It was all about trying to fix the fiscal mess at ABIM by compelling doctors to deliver more cash faster. Rather than a 10-year program, the January 2014 plan declared that MOC would be continuous, with doctors required to complete new requirements every two, five and 10 years. Doctors could pay their new fees annually, and ABIM would recognize the money as revenue when it was paid. Money from doctors who prepaid would be counted as revenue evenly, year after year. In other words, if a physician prepaid for 10 years, rather than booking revenue when ABIM provided the certification services, the group would count one tenth of the payment each year. Had ABIM not been forced to back down on this idea, it was an approach that might have cleaned up the disaster caused by ABIM’s accounting practices—that is, if the group can accomplish that without first falling into bankruptcy. Not even the most secretive organization can keep piling up losses forever while carrying negative asset values on its books. Of course, no one will know what accounting changes ABIM is using to get out of its self-created crisis until next year, when it files its new audited financials, or whether it will continue to rely on deferred revenue. But there are bigger questions ABIM and ABMS have to consider. Why should doctors be forced to keep ladling out cash and spending time away from their practices studying useless information simply because the ABIM is managerially incompetent? And when will ABIM finally start telling the truth to the doctors it supposedly represents? The New York Times Board Certification and Fees Anger Doctors http://well.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/04/13/board-certification-and-fees-anger-doctors/?ref=health By Joshua A. Krisch, April 13, 2015, 5:36 p.m. Dr. Jonathan Weiss is tired of passing exams. A triple-board-certified physician from upstate New York, Dr. Weiss retakes a long written test in each of his specialties — internal, pulmonary and critical care medicine — every 10 years to maintain his board certification. If he opted out, he could still keep his medical license. However, many hospitals would not hire him, and patients would be less likely to seek his expertise. Now, in light of recent changes to the board certification process, Dr. Weiss and thousands of other physicians are rallying against these examinations, which they say are expensive, time consuming and ultimately irrelevant to patient care. “I’m an idiot,” Dr. Weiss said in an interview. “Here I am, going through this ridiculous process that gets harder each cycle, and all the stuff they’re asking me isn’t helping me. I’d argue that it detracts from my ability to be a good doctor.” Passions run high when it comes to so-called maintenance of certification. Some doctors contend that organizations like the American Board of Internal Medicine extort physicians by charging large exam fees, administering draconian tests that must be retaken if not passed, and persuading hospitals to blacklist doctors who buck the system. But the internal medicine board maintains that these exams are voluntary and continually evolving to meet doctors’ needs. Physicians who take them, the board contends, are demonstrating a superior level of commitment to the well-being of their patients. “Knowledge changes really fast and really dramatically,” Dr. Richard Baron, chief executive and president of the board, said in an interview. “One reason for this framework is to have an ongoing and evolving professional articulation of what the good doctor looks like, what the good doctor knows and what the good doctor does.” Dr. Baron’s organization certifies doctors who specialize in internal medicine — about a quarter of all physicians in the United States, including cardiologists and other nonsurgical specialists. Although board certification is not legally tied to state licensure, it is a highly regarded credential that many hospitals and private practices require. Board certification was once a lifetime credential. But in 1990, the American Board of Internal Medicine started requiring physicians to retake certification exams every 10 years. In January 2014, it overhauled its approach again, requiring regular questionnaires throughout each 10-year period, culminating in a thorough written exam. Although the board loosened several of the intermittent requirements in early February, the exams still carry much weight. On its website, the board has a search function for finding out whether doctors are board certified and whether they are participating in the periodic assessments. “We launched the new program and told all 200,000 of our diplomates that the rules were changing,” Dr. Baron said. “We committed to report publicly whether doctors were engaged in this program.” But many doctors railed against the new rules. More than 20,000 cardiologists signed a petition calling for the board to revert to its pre-1990 requirements. Individual physicians have vented on blogs and social media. On Sermo, a closed, anonymous social network for physicians with more than 300,000 active users, the board certification debate rages across lengthy comment threads. “3 months to learn, memorize and regurgitate the meaningless, trivial facts that normally I would just look up on Google,” TedHak wrote in mid-March. “Exactly my experience after almost 30 years of practice as well,” CyclingDoc replied. “It was my last time. I won’t do M.O.C.,” the user added, referring to maintenance of certification. “Thank God I’m ‘old’ and retiring soon!” drzzzzz posted on the same thread. Opponents of the new recertification regimen see it as an unnecessary addition to schedules that afford scarcely enough time for patient care and self-guided education. To maintain their state licenses, most doctors already must complete a number of continuing medical education courses. “Continuing medical education and lifelong learning make better doctors, but not maintenance of certification,” Dr. Wes Fisher, a cardiologist from Illinois who has blogged extensively about the new requirements, said in an interview. “Medical practice is supposed to be evidence based. There are no data that the maintenance-of-certification program makes any difference in what matters: patient outcomes.” Dr. Fisher and others often refer to a pair of studies published in The Journal of the American Medical Association in December. The studies found no correlation between maintenance of certification and better patient outcomes, but they did report a 2.5 percent decrease in Medicare billings. “One of the studies showed a minute decrease in cost, and the other was neutral,” Dr. Weiss said. “None of us were blown away by these articles.” Dr. Weiss speculates that the disconnect between these exams and patient outcomes owes partly to the fact that closed-book exams do not reflect the realities of modern health care. “Nowadays, medicine is an open-resource team approach,” he said. “I get all this information in the room in seconds, and then I use my experience and my knowledge to pull together a plan.” Some physicians are also wary of the fees — as high as $3,000 — that specialty boards charge for maintenance of certification. And the traditionally high failure rate for internal medicine exams means that “applicants have to restudy and retake the test,” Dr. Weiss said. “And you know what? If you retake the test, you have to pay them more money. One could argue they have a perverse incentive to come up with questions that are challenging in a way that is not beneficial to me, but is beneficial to the board.” Dr. Baron of the internal medicine board strongly disputes these claims. The exam questions, he said, were written by a committee of academics and practicing doctors chosen for their depth of knowledge. He said that the material “would be best described as clinical simulations, the sorts of things that most people don’t look up in practice,” but added nonetheless that “we are looking at ways to make resources available during the exam.” Regarding the high price of recertification, Dr. Baron said, “it costs money to produce and deliver the exam, and we also have the costs of running a business and paying salaries.” As for the JAMA studies, Dr. Baron stressed that the 2.5 percent savings attributed to maintenance of certification was not to be taken lightly. “They dismiss that as marginal, but if you’re spending $545 billion on Medicare every year, 2.5 percent is anything but marginal,” he said. In response to outcry from physicians like Dr. Weiss and Dr. Fisher, the internal medicine board issued an official apology in February. “We clearly got it wrong,” the announcement read, acknowledging that the group didn’t deliver a program “that physicians found meaningful.” Although there will still be exams every 10 years, the board committed to reducing certification fees and suspended some of the required intermittent practice assessments and surveys. But some physicians are skeptical. “We’ve caught their attention — they’re getting nervous,” Dr. Weiss said. “But us disgruntled doctors remain concerned that the apology from Dr. Baron is smoke and mirrors and lip service. The battle is far from over.”