Corporate Support for Artistic and Cultural Activities: What

advertisement

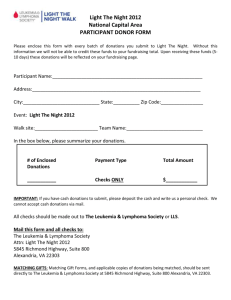

Journal of Cultural Economics 24: 225–241, 2000. © 2000 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlands. 225 Research Note Corporate Support for Artistic and Cultural Activities: What Determines the Distribution of Corporate Giving? MARK S. LECLAIR and KELLY GORDON Department of Economics, Fairfield University, N. Benson Rd., Fairfield, CT 06430, U.S.A. Abstract. This paper examines the allocation of corporate donations among various categories of recipients and the reasons underlying that allocation. An analytical model is utilized to determine the importance of profitability, firm size, advertising expenditures and type of business in determining the level of support for each activity. The results demonstrate that corporate giving to artistic/cultural activities is correlated with advertising expenditures, while donations to educational, civic and health causes are not. Thus, support for culture and the arts is a means of directly promoting the firm, while giving to other causes fulfills the firm’s goals through alternative means. Key words: business objectives of the firm, corporate arts sponsorship 1. Introduction Corporate giving, which has increased at a rate of over eleven per cent per year since the mid-1970s, now represents a significant source of “social spending” within the U.S. Research on corporate giving has focused on uncovering the underlying motives behind corporate donations. In particular, is business support primarily altruistic or self-interested in nature? Obviously, the extent to which society benefits from these expenditures depends on what motivates corporations to make such contributions. Previous examinations of corporate giving have focused on total corporate donations and their motivations. Studies presented by Johnson (1966), Schwartz (1968), Whitehead (1976), Fry, Keim and Meiners (1982), and Arulampalam and Stoneman (1995), as well as a number of authors in Martorella, ed. (1996) all examined the magnitude of corporate contributions and what economic motives might lie behind the observed level of giving. This analysis will examine the allocation of corporate donations within the U.S. to cultural/artistic activities and what motivates businesses to allocate their contribution dollars to this category of giving. Corporations must also decide what percentage of their donations should be devoted to other activities, such as those that support health/human services, 226 MARK S. LECLAIR AND KELLY GORDON Table I. Total corporate donations – 1980–1994 (in millions) Year Funding ($) Real funding ($) (1982–1984 = 100) 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 2359 2514 2906 3627 4057 4472 5179 4980 4809 4893 4752 4750 5521 6305 7103 2759 2683 2965 3584 3853 4103 4691 4315 3997 3886 3552 3447 3888 4324 4745 Source: Internal Revenue Service, Statistics of Income-Corporate Income Tax Returns. education, and civic and community causes. A thorough empirical analysis will be presented to demonstrate that donations to the arts are influenced by factors that are different from those that underlie other types of corporate giving. 2. Trends in Corporate Donations The magnitude of corporate giving, as reported by the U.S. Internal Revenue Service has risen from approximately $2.4 billion in 1980 to just over $7 billion in 1994 (see Table I), despite a decline in contributions from 1988 through 1991. This represents an average annual increase of 8.2 per cent over the 14-year period. In real terms, donations rose from $2.8 billion to $4.8 billion over the same period, an increase of nearly 72 per cent. Contributions to organizations or activities that support education represent, by a significant margin, the greatest percentage of total corporate giving. Key targets of this funding include project or research grants, matching gifts, and departmental grants and capital grants at the post-secondary level. Corporate giving to health and human services causes is the second most important category, averaging 27.8% of total donations over the 11 year period from 1984 to 1994. Civic and Community activities represent a much smaller category of corporate giving, with just 13.5% of total contributions. CORPORATE SUPPORT FOR ARTISTIC AND CULTURAL ACTIVITIES 227 Table II. Patterns of funding for the arts – federal (NEA), and corporate support – 1980–1994 (in millions of current dollars, 1982–1984 = 100) Year Federal Corporate Corporate as % of federal 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 188.1 186.8 133.4 147.5 169.9 171.7 167.1 170.9 171.1 166.7 170.8 166.5 163.0 159.7 158.1 108.7 139.6 145.8 145.2 154.7 187.5 198.7 178.6 183.6 201.2 243.6 265.4 243.6 214.3 189.3 57.8 74.7 109.3 98.4 91.1 109.2 118.9 104.5 107.3 120.7 142.6 159.4 149.4 134.2 119.7 Source: Federal funding, U.S. National Endowment for the Arts, Annual Report, Corporate Support, Survey of Corporate Contributions. Corporate support for the arts, which is the focus of this analysis, has risen measurably since the early 1980s (see Table II). As measured by a Conference Board survey, donations to “culture and the arts” by survey participants stood at $108.8 million in 1980 and rose to $243.6 million by 1992, an increase of over 123%. Activities supported included museums and historical societies, public television and radio, theater, and support for local and regional symphonies. Federal support for like activities, through the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), is included in Table II to demonstrate the rising importance of corporate support. While corporate giving reported to the Conference Board stood at just over half of NEA funding in 1980, by 1992 it exceeded federal spending by over 50 per cent. Since that time, there has been a measurable decline in corporate donations, yet the indicated level of business giving still exceeds federal spending by nearly 20 per cent. Authors such as Useem (1991, p. 330) have noted that those seeking funding might begin to view corporate backing as a viable alternative to government funding, yet the differences in motivations that underlie these two types of funding suggest that corporate support is not a true replacement for the NEA. Corporate managers remain answerable to their shareholders, suggesting that donations must be targeted at improving the fortunes of the firm. Useem also noted that, unlike 228 MARK S. LECLAIR AND KELLY GORDON federal support, corporate contributions are rarely targeted at individual artists or artwork that would be considered too avant-garde. Kenyon (1996), in his examination of business sponsorship in Canada, extended this argument further. He asserts that corporate support for the performing and visual arts tends to strengthen existing power relationships by reinforcing corporate network structures. As a result, Kenyon argues that such donations are unlikely to be a “force of social change” (Kenyon, p. 45). The analysis that follows will focus on the motives that underlie corporate contributions. An empirical model will be developed to test various assertions regarding the primary reasons why businesses contribute to the arts. This model will then be reapplied to the level of corporate support for the alternative categories noted above. This disaggregation of contributions will demonstrate that donations by firms to specific categories of giving are driven by specific motivations. One should then be able to conclude what is unique about corporate donations to the arts. 3. What Determines the Level of Corporate Donations? Previous theoretical work on the motivations behind philanthropy in general include Andreoni (1990), Sugden (1982), Bergstrom, Blume and Varian (1986), and Smith, Kehoe and Cremer (1995). Andreoni argued that giving is driven by the potentially conflicting motives of altruism and the desire to win public praise and acclaim. Sugden and Bergstrom et al. examined the issue of whether charitable contributions can be viewed as an alternative means of supplying a public good. Smith et al. utilized a large sample of observations on household characteristics and giving, and were able to explain a significant proportion of the variation in donations. The authors were unable, however, to separate out the effect of altruism upon giving. The literature that specifically addresses corporate giving is sparse. Johnson (1966) examined how industry structure and performance affected donations, and concluded that pre-tax profits were the primary determinant of corporate donations. This was also the conclusion reached by Useem (1987, 1987a), who notes that total contributions have stabilized at around one per cent of total income. In a subsequent article, he (Useem, 1991) notes that this makes the magnitude of corporate funding somewhat “turbulent”, as giving tends to mirror the business cycle. Johnson, as well as Whitehead (1976), attributed the level of support to the degree of rivalry in specific industries. Useem (1984) and Galaskiewicz (1985) asserted that corporate giving is “enlightened self-interest”, with the latter providing some statistical evidence to support this. Schwartz (1968) and Levy and Shatto (1979) demonstrated a link between corporate giving and advertising expenditures, suggesting that donations may be directly tied to the firm’s attempt to promote itself. Turgeon and Colbert (1992) established a framework under which the firm can analyze its participation in the sponsorship of the arts. The authors argue that such sponsorship CORPORATE SUPPORT FOR ARTISTIC AND CULTURAL ACTIVITIES 229 is increasingly used as a “marketing communications device” by businesses. Fry, Keim and Meiners (1982) regressed the level of corporate giving against advertising expenditures and a variety of other variables that measured motivations. The authors find that contributions are strongly tied to advertising expenditures, as well as to the compensation of corporate officers. Fry, Keim and Meiners argue that this invalidates the argument that such giving is altruistic in nature. Arulampalam and Stoneman (1995) conducted a detailed empirical test of the motivations underlying corporate donations utilizing data on specific firms. The authors used a pooled time-series/cross-sectional model for 53 firms over the 1978–1986 time period. Significant explanatory variables included the corporate tax rate, number of employees, profits, and four industry dummy variables. Overall, Arulampalam and Stoneman seem to confirm previous findings regarding the determinants of corporate giving, although their model did not include advertising expenditures. Useem (1987) emphasized the increasing professionalization and bureaucratization of giving, as firms seek to maximize the benefits from their contribution programs, and how this has affected the magnitude of donations. The author also noted the importance of peer-company comparisons that “force” corporations to raise their level of support to match that of their competitors (see also Useem (1991, p. 333) for further elaboration on this point). The author’s 1986 survey of corporate giving practices in Massachusetts reinforces this conclusion (Useem, 1986, p. 107). Only 29% of companies indicated that the level of NEA support influenced their grants programs, while 50% indicated that the policies of other corporations were a major influence. Non-market forces that determine the level of contributions include firm size, community characteristics and relations with other companies (see Useem, 1988). The author (Useem (1988, p. 81) and Useem (1989, pp. 51, 59)) notes that the single most important determinant of giving is the size of the corporation, with larger business able to have more organized and formal programs. Other significant determinants include the degree of interest of top management and the firm’s position within the community. Kushner (1996) expressed this in terms of stakeholder management, arguing that executives have multiple goals to fulfill in operating the firm, one of which is the maximization of public welfare (Kushner, 1996, p. 240). This stands in contrast to the more traditional view that firms must act to increase shareholder wealth. In certain circumstances, these institutional factors can be as important as economic factors in determining the magnitude of a firm’s contribution program. In Useem’s 1986 survey of Massachusetts firms (Useem, 1986, p. 100), he found that nearly 70 per cent of firms report that the influence of the Chief Executive Officer on both the size and nature of giving programs exceeded that of all other factors. For a thorough review of the literature that addresses the level of corporate support, see Martorella (1996). Kirchberg (1995) examined the relationship between socioeconomic conditions in metropolitan areas and the resulting level of corporate sponsorship of the arts. Utilizing data from eleven U.S. cities for 1977 through 1991, the author demonstrated that corporate support rises 230 MARK S. LECLAIR AND KELLY GORDON both with the educational level of the population and the importance of services in the economic base. Significantly, the author also found that donations rise and fall with the profitability of the corporate sector (i.e. recessions). The importance of regional factors in determining the level of donations was also emphasized by Useem (1988). The author asserted that the most important determinant of corporate giving was the attitude of the business community towards contributions. Finally, Galaskiewicz and Wasserman (1989) argue that corporations temper their support for the arts to match the interests of their clientele and employees. Thus, service industries are more likely to contribute to the arts, since their customer base is more likely to be composed of individuals who care about the arts (a so-called “mimetic process”). The arguments presented above focus on the practices of U.S. businesses. Differences in the institutional and societal environment in other nations may produce some decidedly different patterns of corporate giving. Goncebate and Hajduk (1996) examined the motivations behind donations in Argentina. Although the three most important rationales for supporting the arts were similar to those influencing U.S. corporations, improving the firm’s image, the personal interest of key executives, and as a marketing strategy, 38% of businesses reported that they also gave to offset falling levels of state support (Concebate and Hajduk, 1996, p. 53). This suggests that firms in Argentina have a somewhat higher sense of social responsibility than their counterparts in the U.S. Durand (1996) argues that Brazilian corporations that donate to the arts are motivated both by imagemaking and by the personal interests of a company’s executives and their families, a conclusion that is consistent with the findings on corporate behavior in the U.S. In contrast to Durand’s findings, Kirchberg (1996) concluded that firms in East Germany donate primarily out of a sense of social responsibility, although imagebuilding was the second most important motive given (Kirchberg, 1996, p. 125). Finally, Hitters’ (1996) examination of corporate donations in Rotterdam indicates that firms in the Netherlands give for much the same reason that firms donate in the U.S., with marketing and enhanced public relations given as the primary motives. Thus, although some variations exist in business giving practices overseas, improving the prospects of the firm appears to be a consistent motive. The key difference appears to be an elevated sense of social responsibility in certain nations. 4. The Patterns of Corporate Giving Across Industries The proportion of total contributions that corporations devote to educational causes varies widely across industries, from a high of 50.79% in the Transportation Equipment sector, to a low of 16.56% in wholesale/retail trade (see Table III). In general, the percentage is higher in manufacturing sectors and lower in the services. Donations to organizations that support health/human services activities is highest in the service industries (42 per cent of total giving in the transportation sector, for example) and lowest in non-durable manufacturing. In the printing and publishing 231 CORPORATE SUPPORT FOR ARTISTIC AND CULTURAL ACTIVITIES Table III. Corporate giving – Percentage donated to education, health and human services and civic/community causes, by industry for 1984–1994 Chemicals Electrical machinery Food and allied Paper and allied Petroleum Printing and publishing Transportation equipment Banking Insurance Transportation Wholesale/retail trade Education Health and human services Civic community causes 42.0 45.3 29.3 31.7 45.1 34.5 50.8 27.1 30.5 25.5 16.7 26.7 24.9 31.7 25.9 22.7 21.3 25.5 36.0 35.4 42.0 40.4 13.0 8.3 10.8 14.5 15.1 10.4 9.2 16.2 16.8 9.1 13.6 Source: Conference Board, Survey of Corporate Contributions. sector, just one-fifth of total donations go to activities in this category. Corporate funding of civic/community causes is currently the smallest category of giving, with less than ten per cent of total giving allocated to this type of recipient in several industries. Yet, insurance and banking firms donate one out of every six dollars to civic/community causes. The reasons behind these wide cross-industry variations in contributions are not directly apparent. It will be possible, however, to draw some inferences from the empirical analysis that follows. Useem (1987) noted these differences in donation practices across industries, particularly the tendency of high-tech firms to donate to education causes to support the training of future workers. The percentage of total contributions designated for culture and arts, by industry, is presented in Table IV. These comprise only 7.44% of total donations in the chemical industry during the ten year period from 1984–1993. Similarly, for paper and allied products and transportation equipment, grants to the arts were just over nine per cent of total giving. Conversely, the printing and publishing, transportation and wholesale/retail trade sectors directed more than 15 per cent of total donations to the arts. These differences may arise from the nature of these businesses and the advantages gained by engaging in particular kinds of activities. Firms seeking an innovative image, such as those in the printing/publishing and banking sectors, might find giving to the arts a suitable means of achieving that goal. Useem (1989) attributed variations in the level of funding for the arts to the inter-industry differences in the degree of public contact. Donations to cultural/artistic activities may also be viewed as a means of addressing industry image 232 MARK S. LECLAIR AND KELLY GORDON Table IV. Corporate giving – percentage donated to culture and the arts by industry for 1984–1994 Industry Percent Chemicals Electrical machinery Food and allied Paper and allied Petroleum Printing and publishing Transportation equipment Banking Insurance Transportation Wholesale/retail trade 7.44 9.54 13.15 9.17 14.31 15.06 9.33 14.61 11.63 16.09 15.95 Source: Conference Board, Survey of Corporate Contributions. problems. Corporations in the petroleum industry, for instance, could attempt to reverse the public’s poor impression of the industry through enlightened donations. Useem (1987a) also noted that regional differences exist, with corporations operating in the Mid-west more likely to donate to cultural/artistic causes than firms operating elsewhere. As noted above, authors of previous empirical and theoretical work have suggested a number of motivations behind corporate donations. Firms may be seeking to improve the image of the corporation, thus increasing both sales and profitability. Corporate donations to cultural and artistic activities are prominently displayed in annual reports and corporate promotional literature, presenting an enlightened image to both stockholders and consumers. Senior executives may view donations as a means of increasing their stature in the community. Corporate giving may also be seen as a means of increasing worker morale and satisfaction, presumably reducing employee turnover. Finally, the magnitude of business donations may be partially determined by the economic status of the firm. One would then expect corporate support to rise and fall with the fortunes of the industry, as contributions are more easily justified when the firm is profitable. 5. A Model of Corporate Giving Previous empirical work suggests that image-building is the primary motivation behind corporate donations. Therefore, corporate giving should increase along with advertising expenditures (as in the empirical work by Fry, Keim and Meiners (1982)). If corporate support is targeted at raising employee morale and retention, CORPORATE SUPPORT FOR ARTISTIC AND CULTURAL ACTIVITIES 233 then donations should rise as the number of employees increases. Profits are included in the estimation to determine whether giving is correlated with industry performance, an outcome which would suggest that the magnitude of donations may be at least partly driven by opportunity.1 These three variables will be expressed as a proportion of sales to eliminate size effects. Finally, a dummy variable representing each industry will be incorporated into the estimation (as in the empirical work by Arulampalam and Stoneman (1995)). Not only is this likely to improve the results of the estimation, but it provides useful information on differences across industries. Although it is difficult to include all aspects of Useem’s work, the empirical model will incorporate many of the author’s assertions regarding the determinants of corporate giving. The importance of firm size is reflected in employment levels (see details on estimation below to see why employment was used as a surrogate for sales), while his conclusion that corporations donate approximately one per cent of profits is explicitly part of the estimation. Finally, the inclusion of the binary variables is consistent with Useem’s findings on the importance of industry sector on the degree of funding devoted to cultural and artistic activities. The importance of key executives in determining a corporation’s contribution policy is difficult to quantify in a model of this form, and conclusions regarding the importance of this affect must be analyzed through surveys. 6. Aggregation Issues Consistent with previous empirical work on corporate giving (e.g. Fry, Keim and Meiners, 1995), industry aggregates will be utilized in the estimation. Although this has the decided disadvantage of “washing out” variations in behavior and performance, it eliminates the use of a severely restricted sample that may bias the results (an issue that obviously troubled Arulampalam and Stoneman (1995)).2 The expression of profits, employees, and advertising as a proportion of sales reduces the concern about aggregation of data, as the variables utilized are industry return on sales, employment per unit sales, and advertising per unit sales, commonly utilized measures of overall industry conditions. Alternatively, one could utilize the existing firm-by-firm data on corporate giving. Unfortunately, while the Conference Board publishes specifics on the top 75 corporate donors, the identity of the firms is protected, thus preventing the construction of a time-series sample. Recently (1997), federal legislation was introduced in the U.S. to force businesses to divulge specifics on their contribution programs, but this is being fought both by corporations and by business organizations. Future research in this area is likely to focus on the behavior of specific firms, but at present, empirical work is confined to the aggregate numbers that are available. 234 MARK S. LECLAIR AND KELLY GORDON 7. Pooling Empirical investigations into the philanthropic behavior of U.S. Corporations has been constrained by an insufficient number of time-series observations. Consequently, authors such as Arulampalam and Stoneman have resorted to utilizing pooled cross-sectional and time-series estimations to obtain sufficient degrees of freedom; an approach that will be pursued here. Currently, eleven years of industryby-industry data exists on the beneficiaries of corporate giving. A total of 11 distinct industries were then identified,3 in order to provide 121 total observations. The error terms arising from the estimation will be assumed to be both heteroskedastic and auto-correlated, requiring the use of a Generalized Least Squares (GLS) model. 8. Empirical Model The results reported below reflect five different estimations of the basic model: Cit = F (Ait , Lit , Eit , Di )4 where Cit Ait Lit Eit Di = = = = = Corporate contributions/sales. Advertising by ith industry in tth year/sales. Employment/sales. Industry profits/sales. Industry dummy variables, i = 1, 11.5 The first estimation will use corporate giving to culture and the arts as the dependent variable. The equation will then be re-estimated using donations to education causes, health and human services organizations, civic/community activities, and finally total donations. The results of the latter models will then be compared to those for giving to culture and the arts to determine if significant differences arise. This should provide additional insights into the motives behind corporate contributions. Although Arulampalam and Stoneman have estimated their model in log form, this was presumably a means of reducing the degree of heteroskedasticity affecting the estimation. Since a GLS model will be utilized here, concerns about heteroskedasticity are eliminated, and the model will be estimated without a log transformation. Finally, Arulampalam and Stoneman included a time trend variable in their empirical model. Preliminary analysis of the data set utilized here showed it to be insignificant. CORPORATE SUPPORT FOR ARTISTIC AND CULTURAL ACTIVITIES 235 9. Data Data on corporate donations, cross-referenced by industry and beneficiary, are available annually from the Conference Board’s annual survey on corporate giving (Conference Board, 1984–1994). These figures represent the percentage of total donations relegated to each of five major categories of recipients: Health and Human Services, Education, Culture and the Arts, and Civic/Community Causes. These percentages can then be multiplied by the corresponding figure for “contributions or gifts” published by the Internal Revenue Service in Statistics of Income-Corporation Income Tax Returns (IRS, various dates). This results in a reasonable estimate of total corporate giving in each category. This document also provided figures for both industry profits and sales. Finally, employment statistics were drawn from Employment, Hours and Earnings (U.S. Dept of Labor, various dates). 10. Results The outcomes of the five estimations are presented in Tables V–IX. For the most part, the results are consistent with previous empirical work on corporate giving. Donations to culture and the arts as a percentage of sales rose with advertising expenditures as a proportion of sales (Ait ), with the rate of profitability (Eit ), and with the level of employment per unit sales (Lit ). The coefficients on these three variables are significant at the 1% level, and the model explains just under twothirds of the variation in the donation to sales ratio. The profit-sales ratio is the most significant of the three key variables. Although quite small in magnitude, this coefficient expresses the direct linkage between profitability and the level of support. This provides direct support for Useem’s (Useem, 1987, 1987a) assertions regarding the importance of earnings as a determinant of donations. The significance of advertising expenditures is consistent with the findings of Schwartz, Levy and Shatto, as well as those of Fry, Keim and Meiners. Unlike previous empirical work, however, advertising expenditures are less significant than other factors in determining corporate donations. The key role played by both industry profitability and employment is more consistent with the empirical work of Arulampalam and Stoneman, as well as the findings of Useem. Three of the ten industry dummy variables were significant, representing the petroleum industry, printing and publishing, and banking.6 All three coefficients were positive, indicating higher donations to the arts in these three sectors. Consistent with hypotheses, the higher donations on the part of the petroleum producers are an attempt to address the industry’s persistent image problem. Firms in the printing/publishing and banking sectors more likely view contributions as a means of projecting an enlightened image to the public, a result that is in full agreement with Useem’s findings that service sector firms are more likely to donate to the arts. Although Arulampalam and Stoneman also found inter-industry differences, their study found an increased level of giving in the Food, Alcohol and Tobacco 236 MARK S. LECLAIR AND KELLY GORDON Table V. Regression results – corporate donations to the arts Variable Estimated coefficient T -statistica Advertising/sales Profits/sales Employees/sales Dummy (petroleum) Dummy (print/pub.) Dummy (banking) 0.0013 0.0011 0.0089 0.0541 0.0981 0.0770 3.41 5.78 4.45 2.96 5.74 5.07 a N = 121; Adjusted R-squared = 64.8%; F -stat. = 34.91. All variables significant at the 1% level. Table VI. Regression results – corporate donations to education Variable Estimated coefficient T -statistica Advertising/sales Profits/sales Employees/sales Dummy (chemicals) Dummy (print/pub.) Dummy (insurance) Dummy (transportation) Dummy (wholesale/ret.) –0.00003 0.0023 0.2118 0.2419 0.1196 –0.1267 –0.2196 –0.2261 –0.03b 4.40 4.01 5.78 2.69 –3.68 –4.67 –5.66 a N = 121; Adjusted R-squared = 74.89%; F -stat. = 41.75. b Rejected. All variables significant at the 1% level. Table VII. Regression results – corporate donations to health and human services activities Variable Estimated coefficient T -statistica Advertising/sales Profits/sales Employees/sales Dummy (chemicals) Dummy (food and allied) Dummy (print/pub.) Dummy (banking) –0.0039 0.0021 0.0180 0.2483 0.2547 0.1829 0.1736 –1.55b 5.36 5.14 3.73 2.91 4.90 6.61 a N = 121; Adjusted R-squared = 68.53%; F -stat. = 35.16. b Rejected. All variables significant at the 1% level. CORPORATE SUPPORT FOR ARTISTIC AND CULTURAL ACTIVITIES 237 Table VIII. Regression results – corporate donations to civic/community causes Variable Estimated coefficient Advertising/sales Profits/sales Employees/sales Dummy (electr. mach.) Dummy (banking) 0.0008 0.0020 0.0065 –0.0454 0.0623 T -statistica 1.69b 8.35 3.60 2.50c 3.32 a N = 121; Adjusted R-squared = 50.41%; F -stat. = 23.38. b Rejected. c Significance at the 5% level, all others at 1%. Table IX. Regression results – total corporate donations Variable Estimated coefficient T -statistica Advertising/sales Profits/sales Employees/sales Dummy (chemicals) Dummy (printing/pub.) Dummy (banking) 0.0102 0.0110 0.0294 0.1682 0.5030 0.3544 5.61 11.65 4.00 2.13b 6.55 5.21 a N = 121; Adjusted R-squared = 82.3%; F -stat. = 88.46. b Significance at the 5% level, all others at 1%. and Leisure industries. In agreement with the findings here, Arulampalam and Stoneman did find a higher level of donations in the Financial Services sector. The variations between the two outcomes probably arises from differences in the data set that was utilized. Arulampalam and Stoneman used disaggregated data from the United Kingdom, while this study employed industry-wide observations from the U.S. In addition, while this prior study used total donations as the dependent variable, the first phase of this estimation used only donations to culture and the arts. The results from the estimations utilizing corporate donations to causes other than culture and the arts provide some interesting contrasts (see Tables VI–VIII). For the estimation utilizing donations to education, profitability and employment remain significant, but donations are not positively correlated with advertising expenditures. This appears to conform to the assertion that contributions to education may be motivated by reasons other than the promotion of the firm. In addition, while firms in the printing/publishing industry were more likely to donate to educational causes, a result consistent with the findings for the previous estimation, 238 MARK S. LECLAIR AND KELLY GORDON the rest of the industry effects are entirely different. Donations were significantly higher in the chemical industry, and significantly lower in the transportation, insurance and retail/wholesale trade sector. Generally, then, corporate donations to education are higher in the manufacturing sectors than they are in the transportation or services sectors. The outcomes for both health and human services donations and those to civic/community causes are similar. For the former, both profitability and employment are significant at the 1% level, while advertising expenditures are rejected by the model. The binary variables for chemicals, food/allied, printing/publishing and banking are all positive and strongly significant. Similarly, corporate giving to civic/community activities also rises with profitability and employment, and advertising expenditures are once again rejected. Only two binary variables are accepted by the model, those representing electrical machinery, where donations fall below those of firms in general, and banking, where giving exceeds that of other sectors. Are there significant differences between total corporate giving and that targeted specifically at arts and culture? Table IX presents the results of the estimation that utilized total corporate giving as the dependent variable. The link between advertising expenditures and donations is now substantially stronger than in the first estimation. Once again, both profitability and employment are important determinants of corporate contributions. Total donations are more strongly influenced by advertising expenditures (with a t-statistic of 5.61) than are donations to the arts where the level of employment is more important. 11. Summary and Conclusion Table X contains a complete summary of the empirical results arising from the five estimations. In all cases, both profitability and employment were significant determinants of corporate contributions. Yet, only for total donations and donations to culture and the arts were advertising expenditures significant. This suggests that promotion of the firm is a key motivation behind giving to the arts but is not a determinant of giving to other causes. Thus, the conclusions reached by Schwartz (1968), Fry, Keim and Meiners (1982), and Levy and Shatto (1979) on the importance of self-promotion in determining contribution levels is supported for giving to the arts but not for donations targeted at other categories of giving. This suggests that empirical work that utilized simply total contributions most likely missed some interesting patterns in corporate support. The conclusions reached by Johnson (1968), Useem (1987, 1987a), and Arulampalam and Stoneman (1995) about the significance of profits holds true for all categories of giving. One can reasonably conclude that giving is partly determined by the rising fortunes of a particular industry and the resulting ability to increase donations without upsetting stockholders. 239 CORPORATE SUPPORT FOR ARTISTIC AND CULTURAL ACTIVITIES Table X. Summary of results – significance of variables Factor Arts Education Health Civic Total Profitability Employees Advertising Binary variables Chemicals Electrical mach. Food/allied Paper/allied Petroleum Printing/pub. Transportat. equip. Banking Insurance Transportation Wholesale/retail Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes No Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes No No No No Yes Yes No Yes No No No Yes No No No No Yes No No Yes (<0) Yes (<0) Yes (<0) Yes No Yes No No Yes No Yes No No No No Yes (<0) No No No No No Yes No No No Yes No No No No Yes No Yes No No No Table X also provides some interesting insights into inter-industry patterns of giving. The conclusion reached by Galaskiewicz and Wasserman (1989), that service sector firms donate more than manufacturing firms, appears to hold true only for the banking sector. In not a single one of the four major categories of giving did the insurance, transportation, or wholesale/retail trade sectors exhibit donations that exceeded those of firms in general (in fact, contributions to educational causes were significantly depressed). The pattern of giving in the petroleum industry is also of interest, since only in this sector were donations to culture and the arts increased while contributions to other causes were unaffected. The authors believe this to be a reflection of the relatively negative impression that the public has of firms in this sector of the economy. Donations to the arts provides such businesses with a means of projecting an enlightened image to potential customers. This provides additional evidence to support the conclusion that the support of cultural and artistic activities is primarily a means of promoting the firm. Inter-industry differences also lend support to Useem’s assertion that the donation practices of peer companies are a significant determinant of business giving, as the adoption of similar patterns of support within an industry group helps explain significant cross-industry variations (Useem, 1988). This study does not address the situation raised by Kirchberg (1996) in which contributions in East Germany were partly motivated by a sense of social responsibility. To what degree this can be applied to the U.S. economy is an area for future empirical work. Finally, the importance of factors such as the interest of key executives or the firm’s position within the 240 MARK S. LECLAIR AND KELLY GORDON community must be examined utilizing firm-specific data, information hopefully available to researchers in the future. Notes 1. One could argue that the causation between profits and contributions runs in reverse, with donations resulting in increased profitability. The two variables are measured concurrently here, however, and one would assume that donations would affect profitability only with a lag. 2. Although the use of firm-by-firm data is undoubtedly an improvement, the authors note that the data set is flawed in that it contains only those companies that donate large amounts to charity. In addition, as the authors are using pooled time-series/cross-sectional data, only those companies that were large donors over the entire sample period (1978–1986) were left in the sample. Consequently, only 53 firms were ultimately retained in the data set. 3. The number of industries in the estimation was partly constrained by inconsistencies between industry categories used by the International Revenue Service, and those utilized by the Conference Board. Industries were eliminated if no correspondence could be established. 4. Previous empirical work has also included the difference between corporate tax rates and individual tax rates as a variable, with differences between the two inducing executives to donate through the corporation rather than individually. A quick examination of corporate and individual tax rates, however, shows them to be relatively fixed, and thus unable to explain variations in corporate giving. 5. Inclusion of all eleven binary variables would, of course, preclude estimation of the equation. Preliminary empirical testing was used to eliminate one binary variable from each estimation. 6. To avoid unnecessary clutter, coefficients and t-statistics are included for significant binary variables only. A summary of the significance of all dummy variables in all estimations is contained in Table X. References Andreoni, J. (1990) “Impure Altruism and Donations to Public Goods: A Theory of Warm-Glow Giving”. Economic Journal 100: 464–477. Arulampalam, W. and Stoneman, P. (1995) “An Investigation into the Givings by Large Corporate Donors to U.K. Charities, 1979–1986”. Applied Economics 27: 935–945. Bergstrom, T., Blume, L., and Varian, H. (1986) “On the Private Provision of Public Goods”. Journal of Public Economics 29: 25–49. Conference Board (1980) Corporate Contributions, New York. Conference Board (1984–1994) Survey of Corporate Contributions, New York. Durand, J. (1996) “Business and Culture in Brazil”, in R. Martorella (ed.), Art and Business, Praeger, Westport, CT. Fry, L., Keim, G., and Meiners, R. (1982) “Corporate Contributions: Altruism or for Profits?”. Academy of Management Journal 25: 94–106. Galaskiewicz, J. and Bielefed, W. (1985) Social Organization of an Urban Grants Economy. Academic Press, Orlando, FL. Galaskiewicz, J. and Wasserman, S. (1989) “Mimetic Processes within an Organizational Field: An Empirical Test”. Administrative Science Quarterly 34: 454–479. Goncebate, R. and Hajduk, M. (1996) “Business Support to the Arts and Culture in Argentina’, in R. Martorella (ed.), Art and Business, Praeger, Westport, CT. Hitters, E. (1996) “Art Support as Corporate Responsibility in the Post-Industrial City of Rotterdam, the Netherlands”, in R. Martorella (ed.), Art and Business, Praeger, Westport, CT. CORPORATE SUPPORT FOR ARTISTIC AND CULTURAL ACTIVITIES 241 Internal Revenue Service (various dates) Statistics of Income-Corporation Income Tax Returns. U.S. Government Printing Office. Johnson, O. (1966) “Corporate Philanthropy: An Analysis of Corporate Contributions”. Journal of Business 39: 489–504. Kenyon, G. (1996) “Corporate Involvement in the Arts and the Reproduction of Power in Canada”, in R. Martorella (ed.), Art and Business, Praeger, Westport, CT. Kirchberg, V. (1995) “Arts Sponsorship and the State of the City”. Journal of Cultural Economics 19: 305–320. Kirchberg, V. (1996) “Emerging Corporate Arts Support: Potsdam, East Germany”, in R. Martorella (ed.), Art and Business, Praeger, Westport, CT. Kushner, R. (1996) “Positive Rationales for Corporate Arts Support”, in R. Martorella (ed.), Art and Business, Praeger, Westport, CT. Levy, F. and Shatto, G.M. (1979) “The Evaluation of Corporate Contributions”. Public Choice 33: 19–28. Martorella, R. (1996) “Corporate Patronage of the Arts in the United States: A Review of the Research”, in R. Martorella (ed.), Art and Business, Praeger, Westport, CT. Schwartz, R.A. (1968) “Corporate Philanthropic Contributions”. Journal of Finance 22: 479–497. Smith, V., Kehoe, M., and Cremer, M. (1995) “The Private Provision of Public Goods: Altruism and Voluntary Giving”, Journal of Public Economics 58: 107–126. Sugden, R. (1982) “On the Economics of Philanthropy”. Economic Journal 92: 341–350. Turgeon, N. and Colbert, F. (1992) “The Decision Process Involved in Corporate Sponsorship for the Arts”. Journal of Cultural Economics 16: 41–51. U.S. Department of Labor – Bureau of Labor Statistics (various dates) Employment, Hours and Earnings. U.S. Government Printing Office. Useem, M. (1984) The Inner Circle: Large Corporations and the Rise of Business Political Activity in the U.S. and the U.K.. Oxford University Press, New York. Useem, M. (1986) “Corporate Contributions to Culture and the Arts: The Organization of Giving and the Influence of the Chief Executive Officer and of Other Firms on Company Contributions”, in P. DiMaggio (ed.), Nonprofit Enterprises in the Arts, Oxford University Press, New York. Useem, M. (1987) “Corporate Philanthropy”, in W. Powell (ed.), The Non-Profit Sector: A Research Handbook, Yale University Press, New Have, pp. 340–359. Useem, M. (1987a) “Trends and Preferences in Corporate Support for the Arts”, in R. Porter (ed.), Corporate Giving (4th edition), American Council for the Arts, New York, pp. ix–xv. Useem, M. (1988) “Market and Institutional Factors in Corporate Contributions”. California Management Review 30: 77–88. Useem, M. (1989) “Corporate Support for Culture and the Arts”, in M. Wyszomirski and P. Clubb (eds.), The Cost of Culture, American Council for the Arts, New York. Useem, M. (1991) “Corporate Funding of the Arts in a Turbulent Environment”. Non-Profit Management and Leadership 1: 329–343. Whitehead, P. (1976) “Some Economic Aspects of Corporate Giving”, Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, Virginia Polytechnic Institute.