Introduction: 1960 – a year of destiny

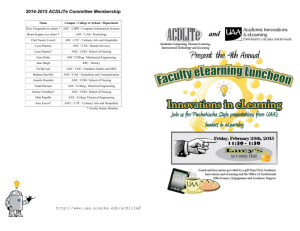

advertisement