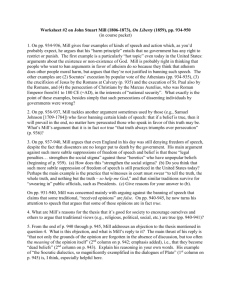

Mill Liberty2

advertisement

Mill on Liberty: Lecture Two Recap: Rights and Utility. Mill argues that the ‘harm principle’ – that nobody’s freedom is to be limited except to prevent harm to other persons – is founded in utility. It would be easy to found it on a simple assertion of right: everyone has a right to act as she or he chooses, so long as no harm is caused to others; but for a utilitarian, rights cannot be ultimate. They need a foundation, and that must be utility. It is not hard to establish the utility of rights in general – such as property rights; a system of powers of control and immunity to interference makes economic life and much else a lot easier. The larger question is whether Mill can get an absolute right to non-interference except for harm-prevention to others out of utility; this means, for instance, that others cannot interfere to protect you from yourself; and they cannot interfere to make you do all you can for everyone else (except in a few marginal cases such as saving a drowning child and serving on a jury.) Beyond that, there is a larger question still, which is what the utility of a man as a progressive being amounts to. So, we should work our way through eight questions a) is such strong anti-paternalism acceptable; b) do we have a clear idea of what harm is (and how it differs from merely upsetting people); c) what are the implications for freedom of thought and speech; d) does the ‘harm principle’ cover offensiveness (and should it); e) why should we not make people do all that they can for society; f) what is the problem posed by what Mill thinks of as hard cases; g) is man a ‘progressive being;’ h) what is the tyranny of opinion? a) Anti-paternalism: Mill allows some exceptions – such as the case of a man about to cross a dangerous bridge that he doesn’t know is dangerous – but very few; consider such rules as those requiring us to wear seat belts or motocycle helmets; and the laws against dangerous drugs. Some features of these may involved harm to others; most are straightforwardly paternalist. Mill is in a minority; but he is not without resources: people often think the choice is between making people be sensible 1 and letting them go to hell in a handcart, but don’t forget Mill’s insistence on the right to urge, entreat, persuade, cajole and so on. b) Harm: this is a very vexed topic; widen the idea a bit and nothing seems to be left out – what if my lectures subvert your faith and imperil your immortal soul? Or that you have strange views absolutely anything and any contradiction is intolerable? How is harm different from ‘being upset’? Plainly the notion of harm is to to do with impairing people’s ordinary functioning; but then need some story about what does that, and it may be hard to get one; easy cases are easy, and harder cases less so – not surprisingly. c) Freedom of Speech: it is essential to distinguish between ‘merely’ saying something harsh and inciting violence: Mill’s example of the corn-dealer; no argument for free-speech can override lying, fraud etc. What about offensive speech? Mill insists we permit it, subject to the point about incitement. Being upset is not being harmed, but the precursor to being made to think, which is a benefit not a harm. d) Offensiveness: there are many variations in this issue, most of them not fit to be described in polite company; but think why we don’t let people walk around the street naked; they not we catch cold. Mill offers one sentence on the subject, but no exploration: the issue is publicity – a blameless husband and wife may not have sexual intercourse in the street, but a murder is no less criminal for taking place in private. Many acts are offensive if done in public, which Mill takes to be a matter of manners, which may underestimate their importance. e) Compulsory Virtue: the most important issue in many ways, because of Mill’s ambivalent reactions to Comte and his fellow-utilitarians; the question is whether a utilitarian really wouldn’t want to make people do what was maximally valuable to society. There are arguments against doing it stemming from questions about the difficulty of knowing what a person ought to do for the best, questions about coordination, and questions about enforcement costs. But, the ordinary rights-based view is that there’s a conflict between our right to choose and overall welfare. Mill has several arguments at once; partly about information, but mostly about it mattering 2 what sort of people we turn into. Compulsory virtue is inconsistent with our being the right sort of people. f) Hard Cases: there could be many others than Mill produces. What they all have in common is that we seem to restrict the freedom of the wrong people – we forbid gambling dens, but it’s a bargain between den-owner and gambler; we forbid prostitution, but it’s a contract for the sale and purchase of sexual services; we forbid the sale of hard drugs… and so on. g) ‘Man as a Progressive Being: Mill is actually ambivalent; he thinks deterioration is the natural order, so we have to push against that tendency; no coasting to perfection, but an energetic battle against our weaker selves. But all Mill’s arguments depend on the thought that we want to revise – or will eventually see the point of being able to revise – our ideas about ourselves and what is best suited both our individual natures and human nature as such. h) The tyranny of opinion: finally, why is this a Victorian or more generally a modern piece of work? Because the kind of tyranny it fears is not old-fashioned and violent, but insidious and self-destructive. 3