9,728mm

B O L D V I S I O N S I N E D U C AT I O N A L R E S E A R C H

Civics Education for the 21st Century

Mordechai Gordon (Ed.)

Quinnipiac University, Hamden, CT

Reclaiming Dissent is a unique collection of essays that focus on the value of dissent for the survival of democracy in the United States and the role that education

can play with respect to this virtue. The various contributors to this volume share

the conviction that the vitality of a democracy depends on the ability of ordinary

citizens to debate and oppose the decisions of their government. Yet recent history in the United States suggests that dissent is discouraged and even suppressed

in the political, cultural and educational arenas. Many Americans are not even

aware that democracy is not primarily about voting every four years or majority

rule, but about actively participating in public debates and civic action. This book

makes a strong case for the need to reclaim a tradition in the United States, like

the one that existed during the Civil Rights Era, in which dissent, opposition, and

conflict were part of the daily fabric of our democracy. Teacher educators, teacher

candidates, new teachers, and educators in general can greatly benefit from reading this book.

Reclaiming Dissent

Reclaiming Dissent

B O L D V I S I O N S I N E D U C AT I O N A L R E S E A R C H

Reclaiming Dissent

Civics Education for the 21st Century

Mordechai Gordon (Ed.)

Mordechai Gordon (Ed.)

ISBN 978-90-8790-884-3

SensePublishers

SensePublishers

BVER 27

Reclaiming Dissent

Bold Visions in Educational Research

Volume 27

Series Editors:

Kenneth Tobin, The Graduate Center, City University of New York, USA

Joe Kincheloe, McGill University, Montreal, Canada

Editorial Board:

Heinz Sunker, Universität Wuppertal, Germany

Peter McLaren, University of California at Los Angeles, USA

Kiwan Sung, Woosong University, South Korea

Angela Calabrese Barton, Teachers College, New York, USA

Margery Osborne, Centre for Research on Pedagogy and Practice Nanyang Technical

University, Singapore

W.-M. Roth, University of Victoria, Canada

Scope:

Bold Visions in Educational Research is international in scope and includes books from two areas:

teaching and learning to teach and research methods in education. Each area contains multi-authored

handbooks of approximately 200,000 words and monographs (authored and edited collections) of

approximately 130,000 words. All books are scholarly, written to engage specified readers and catalyze

changes in policies and practices. Defining characteristics of books in the series are their explicit uses of

theory and associated methodologies to address important problems. We invite books from across a

theoretical and methodological spectrum from scholars employing quantitative, statistical, experimental,

ethnographic, semiotic, hermeneutic, historical, ethnomethodological, phenomenological, case studies,

action, cultural studies, content analysis, rhetorical, deconstructive, critical, literary, aesthetic and other

research methods.

Books on teaching and learning to teach focus on any of the curriculum areas (e.g., literacy, science,

mathematics, social science), in and out of school settings, and points along the age continuum (pre K to

adult). The purpose of books on research methods in education is not to present generalized and

abstract procedures but to show how research is undertaken, highlighting the particulars that pertain to a

study. Each book brings to the foreground those details that must be considered at every step on the way

to doing a good study. The goal is not to show how generalizable methods are but to present rich

descriptions to show how research is enacted. The books focus on methodology, within a context of

substantive results so that methods, theory, and the processes leading to empirical analyses and

outcomes are juxtaposed. In this way method is not reified, but is explored within well-described

contexts and the emergent research outcomes. Three illustrative examples of books are those that allow

proponents of particular perspectives to interact and debate, comprehensive handbooks where leading

scholars explore particular genres of inquiry in detail, and introductory texts to particular educational

research methods/issues of interest. to novice researchers.

Reclaiming Dissent

Civics Education for the 21st Century

Mordechai Gordon

Quinnipiac University, Hamden, CT, USA

SENSE PUBLISHERS

ROTTERDAM/BOSTON/TAIPEI

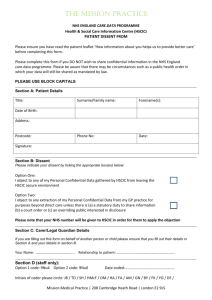

A C.I.P. record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-90-8790-884-3 (paperback)

ISBN 978-90-8790-885-0 (hardback)

ISBN 978-90-8790-886-7 (e-book)

Published by: Sense Publishers,

P.O. Box 21858, 3001 AW

Rotterdam, The Netherlands

http://www.sensepublishers.com

Printed on acid-free paper

All Rights Reserved © 2009 Sense Publishers

No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any

form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording or

otherwise, without written permission from the Publisher, with the exception of any material

supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system,

for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work.

For Joe Kincheloe

Who filled the world with insight, hope and unmitigated joy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First of all, I would like to thank Peter de Liefde, my publisher at Sense

Publishers, who has given me a tremendous amount of support throughout

the work on this book. It has been a pleasure to work with Peter on this

project. I would like to personally acknowledge all the contributors to this

volume: Marvin Berkowitz, Sean Duffy, Gloria Holmes, Michael James,

Bill Puka, Sarah Stitzlein and Joel Westheimer. This book would not have

been possible without their dedication and efforts to bring it to fruition.

Finally, I want to thank my wife, Gabriela Gerstenfeld, who since she often

disagrees with me, has helped me come to appreciate the value of dissent.

vii

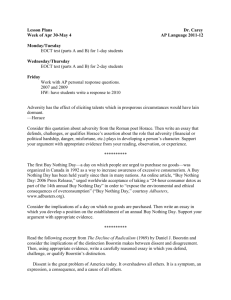

CONTENTS

Introduction

Mordechai Gordon

1

Part I

DISSENT UNDER ATTACK

1

The Meaning and Value of Dissent in a Democratic Society

Mordechai Gordon

2

Historical, Political, and Legal Efforts to Squash Dissent

in the United States

Sean P. Duffy

27

“But They Chose Segregation:” A Case Study of Mexican

Immigrant Resistance in California

Michael E. James

49

Unfit for Mature Democracy: Dissent in the Media

and the Schools

Joel Westheimer

65

3

4

11

Part II

DISSENT AND EDUCATION

5

Dissent: Pulling Teachers off the Sidelines and Back

Into the Democratic Game

Sarah Stitzlein

6

Dissent and Character Education

Marvin W. Berkowitz and Bill Puka

7

Power Concedes Nothing without Demand: Educating Future

Teachers about the Value of Dissent in a Democratic Society

Gloria Graves Holmes

8

Toward a Pedagogy of Dissent

Mordechai Gordon

89

107

131

153

About the Contributors

167

ix

MORDECHAI GORDON

INTRODUCTION

The first amendment of the United States Bill of Rights states that:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or

prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech,

or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to

petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

There is little doubt that the founding fathers of the United States were

aware of the value of dissent for the life of a democracy when they decided

to mandate, in the very first amendment of the Constitution, the fundamental

human right of free speech. For freedom of speech, as the first amendment

is written, implies a commitment by the government to value diverse opinions,

the ability to demonstrate and voice opinions that are not popular, and the

right to dissent against a government decision or law.

However, recent events in the Unites States suggest that the government

has not lived up to its promise to protect and value dissent. For instance, the

2001 USA PATRIOT Act has legitimized the use of warrantless wiretaps,

expanded the use of detentions, and led to the restrictions on the access

of the media and protestors to the President and other national and world

leaders. In this way, this Act has made it more difficult to organize and

voice opposition to the actions of the government like the war in Iraq, since

ordinary citizens may now be more afraid of being targeted. More importantly, the PATRIOT Act has led to a weakening of the spirit of dissent in

the United States by creating an atmosphere in which any opposition to laws

or actions that are intended to “defend” America are deemed unpatriotic or

un-American.

Besides the United States government, the mainstream media has also

played a key role in undermining dissent in this country. For one thing,

analysis from critics such as Noam Chomsky, Amy Goodman, and Seymour

Hirsch is noticeably absent from the opinion pages of our major newspapers.

Equally troubling, is the fact that the mainstream media does not cover many

of the burning issues like healthcare, immigration or the wars in Iraq and

Afghanistan in a thorough and balanced way. Many important issues that

are raised by the media are covered in a cursory and often biased manner,

M. Gordon (ed.), Reclaiming Dissent: Civics Education for the 21st Century, 1–7.

© 2009 Sense Publishers. All rights reserved.

GORDON

thereby giving their audience a superficial picture of the problem. Moreover,

the mainstream media like to pretend that they are merely reporting the

news; they are not typically aware of the fact that they also serve as

knowledge producing agencies. The point is that most of the media in the

United States not only do not cover the voices of opposition, but also, through

their surface coverage of important news items, reduce the likelihood that

ordinary citizens will rise up to engage in acts of dissent.

Finally, the education system in the United States shares the blame for

not helping students develop critical thinking skills and learn about the value

of dissent in a democratic society. As John Gatto (2002) writes in his book

Dumbing Us Down: The Hidden Curriculum of Compulsory Schooling.

The logic of the school-mind is that it is better to leave school with a tool

kit of superficial jargon derived from economics, sociology, natural

science, and so on than with one genuine enthusiasm. But quality in

education entails learning about something in depth… Meaning, not

disconnected facts, is what sane human beings seek, and education is a

set of codes for processing raw data into meaning. Behind the patchwork

quilt of school sequences and the school obsession with facts and

theories, the age-old human search for meaning lies well concealed.

(pp. 3–4)

Thus, most schools in this country still emphasize the study of disconnected

facts and isolated skills rather than getting students to learn about important

issues in depth. As Gatto noted, students leave these institutions with very

little enthusiasm to engage in the kind of thorough examination of issues and

civic action that are essential for a thriving democracy.

This book focuses on the value of dissent for the survival of our democracy

and the role that education and schooling can play with respect to this

virtue. The idea for this book comes out of my interest in politics and education and my deep concern about the erosion of democracy in the United

States in the last several decades. One of the most striking characteristics

of this erosion is the fact that dissent is discouraged and even suppressed

in the mainstream media, in our public schools, and in public debates in

general. Particularly troubling is the way in which conservative leaders and

groups are pushing schools to support their reactionary agenda, one that

emphasizes standardization, traditional notions of authority, and blind

patriotism. Such an agenda undermines the development of those skills and

facilities students need to become critical and active citizens in a democracy.

As a result, the meaning and value of dissent for the life of a democracy is

lost upon most students and citizens in the United States. Indeed, as one of the

key democratic virtues, dissent seems to be all but forgotten in this country.

2

INTRODUCTION

Most books on civics or democratic education fall into three general

categories. The first category attempts to address the following questions:

Who should have the authority to shape the education of future citizens?

Why should they enjoy this authority? And what are the democratic purposes

of public schooling? A good example of this approach to civics education is

Amy Gutmann’s (1987) well known book Democratic Education. In this book,

Gutmann explores the practical implications for educational policy in the

United States of a democratic theory of education.

Another set of books on civics and democratic education is one that

examines the state of education in our democracy with respect to all the

citizens, in particular those people that are traditionally excluded or marginalized. These books generally argue that the well-being of the American

democracy requires a good education for all, not some, of its citizens and

that a worthy education cannot discriminate on the basis of race, gender,

nationality, religion, lifestyle, physical disability, and so forth. For instance,

Goodlad, Mantle-Bromely and Goodlad (2004) argue that “the provision

of total inclusion is a moral imperative in a democracy and,…, a practical

necessity for the health of all and for the continued renewal of a democratic

culture” (p. 7).

A third set of books that deal with the issue of citizenship and democratic

education is one that in some way engages the following question: What

are the essential capacities or dispositions that young people need to have

in order to engage in democratic activities such as deliberation and action?

Patricia White’s (1996) Civic Virtues and Public Schooling: Educating

Citizens for a Democratic Society is an example of a book that addresses

this question in depth. In her book, White identifies hope, confidence,

courage, self-respect and self-esteem, friendship, trust, honesty and decency

as those “dispositions that democrats need but that have to be shaped to take

a particular form in a democratic society” (p. 3). White devotes a full chapter

to explaining what each of these dispositions entails as well as how educational institutions might cultivate these virtues in students.

Reclaiming Dissent: Civics Education for the 21st Century does not fall into

any of the above categories of books that deal with civics and democratic

education. The uniqueness of this book is in its focus on only one

democratic virtue (dissent), which the authors use as a lens to consider the

issue of a worthy education in a democratic society. This book is divided into

two main parts, each of which includes four chapters. Part one, examines the

value of dissent for a democracy as well as historical and current efforts to

suppress dissent in the United States. The contributors to part one highlight

both the efforts to contain resistance to the government and some successful

attempts to oppose its policies and practices. Part two focuses on the

3

GORDON

implications for education and teaching that can be gleaned from a

pedagogical approach that embraces dissent as a democratic virtue.

In chapter one, “The Meaning and Value of Dissent in a Democratic

Society,” Mordechai Gordon asserts that consensus destroys democracy and

that a democratic society can only flourish to the extent that dissent becomes

an integral part of its underlying structures and processes. Gordon begins his

discussion by exploring the benefits as well as the limitations and dangers

that consent poses for a democratic society. Next, he examines the meaning

and value of dissent by focusing on the lessons we can learn about dissent

from the examples of three famous dissidents: Socrates, Thoreau, and

Angela Davis. In the last part of his chapter, Gordon reflects on a number

of limitations of dissent as well as on the main differences between

reasonable and thoughtless dissent.

In the next chapter, “Historical, Political, and Legal Efforts to Squash

Dissent in the United States,” Sean Duffy argues that the suppression of

dissent in American civic culture is fundamentally tied to national cultural

traits such as xenophobia, a desire for conformity, and a fundamental

distrust of radical movements and beliefs. In his chapter, Duffy shows that

throughout American history, legal and governmental efforts to squash

dissent have been most fervent in times of national crisis characterized by

increasing levels of immigration, economic recession and involvement in

outside conflict. At such times, governments at all levels can outstrip Constitutional checks to suspend individual civil liberties particularly with regard

to immigrants, non-nationals and radical organizations. Duffy’s chapter

traces such impulses from the first period of xenophobic crisis in the 1790s

through the Red Scares of the early 20th Century and the more recent

reactions to the attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon in 2001.

Chapter three by Michael James is titled “But they chose segregation:

A Case Study of Mexican Immigrant Resistance in California.” In this

chapter, James argues that the history of dissent in American education is

not confined to highly publicized, large scale mass protests but can often be

embedded within covert actions that all too frequently go undetected by the

dominant culture. Relying on the seminal work of political anthropologist

James Scott, this chapter analyzes the ways subordinate communities protest

asymmetrical relations of power without risking direct confrontation. By

examining one case study in detail—Mexican immigrant workers in turnof-the-century Pasadena, California—James illustrates how resistance to

oppression is articulated by those who have little means of formal participation within the political process.

In his contribution to the book, “Unfit for Mature Democracy: Dissent in

the Media and the Schools,” Joel Westheimer examines the role of the

4

INTRODUCTION

media in revealing or concealing dissent following the September 11, 2001

attack on the United States and the impact of this attack on schools. Through

an examination of media trends, civic education policies, and curricular

changes during the seven ensuing years, Westheimer’s chapter focuses on

the place of dissent in democratic societies and the threats to democratic

deliberation resulting from an ever-narrowing civic agenda. Westheimer’s

chapter asks what we might demand of the media and the schools for a

proper “mature democracy” to flourish.

The remaining four chapters of this volume focus on what a pedagogical

approach that embraces dissent might mean for the education of democratic

citizens. In chapter five, “Dissent: Pulling Teachers off the Sidelines and

Back into the Democratic Game,” Sarah Stitzlein claims that political dissent

as an art of democracy is at risk in the current age of accountability

and standardization, as well as in the larger culture of anti-intellectualism

and enforced consensus. Drawing upon the work of famous dissidents and

teacher interviews, Stitzlein describes processes for teaching skills of

dissent as teachers themselves engage in opposition to problematic aspects

of the No Child Left Behind Act. She highlights civics education as one

key location for the cultivation of skills of dissent within students. Stitzlein

concludes her chapter with a call for teachers to both develop and demonstrate dissent within schools as they guide students through learning the

structural and cultural components of democracy.

In Chapter six, “Dissent and Character Education,” Marvin W. Berkowitz

and Bill Puka assert that dissent is a necessity in a self-governing society

and that the inclination and capacity for dissent can be understood as an

aspect of an individual’s character. Berkowitz and Puka maintain that

schools in democracies have long been understood to carry a major part

of the charge for socializing the character of each subsequent generation.

Therefore, character education should be targeted in part toward education

for the character of dissent. In their chapter, Berkowitz and Puka examine

the character of dissent and how it can be promoted, especially in schools.

They offer a taxonomy of eight core aspects of the character of dissent and

how each can be promoted pedagogically. They conclude with an examination of three school-based programs, which while not all claiming to

promote the character of socially-responsible dissent, may nonetheless be

construed as doing so.

Chapter seven by Gloria Holmes is entitled “Power Concedes Nothing

without Demand: Educating Future Teachers about the Value of Dissent in

a Democratic Society.” In her chapter, Holmes shows that multicultural

education simultaneously embodies dissent and the promise of democracy,

while providing one of the most important and controversial challenges to

5

GORDON

American education in the 21st century. Beginning with an historical overview

that begins with the 1630 myth of America as a shining “city on a hill,” she

discusses the origins of America’s dream as a place that values individual

rights and embraces diversity and multiple perspectives. Holmes then moves

to a discussion of the dynamics of dominant privilege, a concept essential to

any discussion of diversity, dissent and multicultural education. The chapter

includes a case study centered on a discussion of race as well as excerpts

from journals of teacher candidates, which reveal the impact of multicultural

education on their belief systems. Holmes concludes her chapter by showing

that becoming a multicultural educator is a transformative and potentially

life-changing process because it requires one to critically examine personal

beliefs and to understand how those beliefs inform classroom practice.

In the final chapter of this book, “Toward A Pedagogy of Dissent,”

Mordechai Gordon takes a close look at a number of examples of several

teachers and one school that have attempted to cultivate students who are

critical thinkers and responsible dissenters. Gordon begins his analysis by

considering some of the difficulties, which those educators in the United

States who are committed to fostering dissent are likely to encounter. He

then presents a number of things that various teachers and one school have

done to foster dissent in their classrooms. Gordon concludes his chapter by

reflecting on the lessons that can be gleaned from these cases for a worthy

education in a democratic society.

The various contributors to this volume share the conviction that the

vitality of a democracy depends on the ability of ordinary citizens to debate

and oppose the decisions of their government. Yet recent history in the

United States suggests that dissent is discouraged and even suppressed in

the political, cultural and educational arenas. Many Americans are not even

aware that democracy is not primarily about voting every four years or

majority rule, but about actively participating in public debates and civic

action. Democracy is about protecting the rights of minorities, respecting

diverse viewpoints, values and lifestyles, and cherishing the fundamental

right to dissent. We need to reclaim a tradition in the United States, like the

one that existed during the Civil Rights Era, in which dissent, opposition,

and conflict were part of the daily fabric of our democracy.

As I write this Introduction, Barack Obama has just been elected the 44th

President of the United States. The grass roots movement that he inspired

and mobilized is a sign that there is hope and hunger in this country for a

new type of politics, one which values the contributions that ordinary

Americans can make in bringing about social change. My hope is that the

mass movement, which helped elect the first African American President in

the United States, will not be content to remain idle, marveling in its victory.

6

INTRODUCTION

Far more important than the unprecedented results of this election, is the

prospect that civic engagement and dissent will once again become part of

the everyday fabric of the United States democracy.

REFERENCES

Gatto, J. T. (2002). Dumbing us down: The hidden curriculum of compulsory schooling. Gabriola

Island, BC: New Society Publishers.

Goodlad, J. I., Mantle-Bromley, C., & Goodlad, S. J. (2004). Education for everyone: Agenda for

education in a democracy. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

Gutmann, A. (1987). Democratic education. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

White, P. (1996). Civic virtues and public schooling: Educating citizens for a democratic society.

New York: Teachers College Press.

7

Part I Dissent Under Attack

MORDECHAI GORDON

THE MEANING AND VALUE OF DISSENT

IN A DEMOCRATIC SOCIETY

“Consensus destroys democracy!”

(Dr. Luis Alberto Lacalle, Former President of Uruguay, 1998)

INTRODUCTION

Anyone who has taken the time to watch the State of the Union addresses

in the last eight years may have noticed that there is something terrifyingly

similar between the way in which the senators and representatives responded

to the President’s remarks and how the Chinese parliament members reacted

to Mao’s speeches in the middle part of the twentieth century. Those long

pauses of almost unanimous stand-up applause every couple of minutes are

reminiscent of the footage depicting the great adulation that Mao received

during the heyday of Communist China five decades ago. To be sure, the

State of the Union speech is a carefully scripted spectacle, including audience

members who are hand-picked to create a feeling of pride, strength, and

patriotism. But it seems to me that this event should also give us reason to

pause and reflect on what is happening to the American democracy today.

In particular, we need to take a serious look at the dangers that the lack of

dissent in the United States poses to the strength of our public schools, the

power of our free press, and the integrity of our political institutions.

By dissent, I mean the rejection of the views that the majority of people

hold. To dissent implies to disagree with or withhold consent from a proposal,

law, or an action of a government or a group of people in power. Dissent is

usually associated with difference of opinion, disagreement and nonconformity

with conventional views or sentiments. The list of famous dissidents includes

people such as Gandhi, Martin Luther, Rosa Parks, and Salman Rushdie, to

mention only a few. These dissidents were individuals who were willing to

sacrifice personal comfort and security for the sake of exposing some serious

social problem and establishing a more humane and democratic society.

To illustrate my point about the dangers that the decline of dissent poses

for the American democracy, it is useful to look at the war in Iraq. It is well

known that almost all the Senators and Representatives from both parties

M. Gordon (ed.), Reclaiming Dissent: Civics Education for the 21st Century, 11–26.

© 2009 Sense Publishers. All rights reserved.

GORDON

supported the initial invasion of Iraq in March of 2003, despite the lack of

evidence to substantiate the administration’s claims that Saddam Hussein

was amassing weapons of mass destruction and that he intended to use

these weapons against the West. It is also well known that the majority of

people in the United States did not support the preemptive invasion of Iraq

without the U.N. approval, even though the administration went to great

length to create an atmosphere of fear and panic in this country following

the terrorist attacks of September 11th, 2001.

Less well known is that the mainstream media in the United States sounded

the war drums prior to the invasion of Iraq, downplayed the amount of

dissent that existed for this war among ordinary people and grass root organizations, and gave much more air time to people who supported the war

than to those who opposed it.1 Today, six years after the invasion of Iraq,

when it is clear that the United States has thrust itself into something that it

does not know how to get out of, there is still not enough informed debate

among politicians, the press, and ordinary people about the colossal failure

of this offensive. During the first two years after the invasion, even public

news networks like NPR and PBS rarely questioned whether or not the

United States should even be in Iraq, reserving their criticism to specific

shortcomings of various military, civic, and humanitarian operations in that

country. In short, there seems to be a tacit assumption—shared by politicians,

media leaders and even some prominent college professors—that dissent is

incompatible with patriotism and that support for this country means not

challenging the decisions of the government too much.

In contrast, in this chapter I argue that consensus destroys democracy

and that a democratic society can only flourish to the extent that dissent

becomes an integral part of its underlying structures and processes. I begin

my discussion by exploring the benefits as well as the limitations and dangers

that consent poses for a democratic society. Next, I examine the meaning

and value of dissent by focusing on the lessons we can learn about dissent

from the examples of three famous dissidents: Socrates, Thoreau, and Angela

Davis. In the last part of this chapter, I reflect on a number of limitations of

dissent as well as on the main differences between reasonable and thoughtless dissent.

THE PROBLEM WITH CONSENT

Every society, including a democratic one, cannot exist and thrive without

some beliefs and values that its citizens share. As Alexis de Tocqueville

(2000) noted:

12

THE MEANING AND VALUE OF DISSENT

For without common ideas there is no common action, and without

common action men still exist, but a social body does not. Thus in

order that there be society and, all the more, that this society prosper,

it is necessary that all the minds of all the citizens should be brought

and held together by some principal ideas; and this cannot happen

unless each of them sometimes comes to draw his opinions from one

and the same source and unless each consents to receive a certain

number of ready-made beliefs. (p. 407)

For Tocqueville, who was intrigued by the fledgling democracy in the United

States, the society he traveled through in 1831 could not exist unless its

citizens held in common certain core principals and values like equality and

freedom. Such basic principles and values are normally accepted or taken

for granted by citizens rather than questioned or challenged.

In Tocqueville’s view, the taken-for-granted beliefs and values are

necessary not only for the existence of society but also for the well being of

individuals. “If man were forced to prove to himself all the truths he makes

use of every day,” Tocqueville wrote, “he would never finish. He would

exhaust himself in preliminary demonstrations without advancing” (pp.

407–408). Given both time constraints and the limits of an individual’s

intelligence, each person is forced to take on trust a host of facts and beliefs

that one has neither the time nor the power to verify for oneself. On the

basis of these accepted facts and beliefs, each individual creates for himself

or herself a set of opinions and values, yet the groundwork for these views

is usually never questioned. Tocqueville believed that this condition is not

only necessary but also desirable since otherwise each individual would be

condemned to finding out everything for oneself, making it almost impossible to explore any topic in depth.

Yet, while Tocqueville recognized the benefits for both society and

individuals of having some shared ideas, he was also keenly aware of the

dangers that the taken-for-granted beliefs pose for the citizens of a democracy. He emphasized that the public, by which he meant the majority

opinion, does not try to persuade the minority of the validity of its beliefs.

Rather, “it imposes them and makes them penetrate souls by a sort of

immense pressure of the minds of all on the intellect of each” (p. 409). Thus,

Tocqueville was concerned that the majority viewpoint in the United States

would overshadow minority opinions and that unpopular truths would no

longer be spoken. Moreover, he correctly called our attention to the danger

of allowing the majority to simply supply individuals with ready-made

opinions, thereby relieving them of the obligation to form their own. Not

having lived through the age of mass media and their attempt to mobilize

support for the powerful elite, it is amazing how Tocqueville was able to

13

GORDON

foreshadow how a democratic society such as the United States could

willingly induce its citizens to trust the general will and give up thinking.

Indeed, when one reads Democracy in America, one is struck by the fact

that many of Tocqueville’s observations still hold true today. For instance,

he remarked in his discussions on the tyranny of the majority that “I do not

know any country where, in general, less independence of mind and

genuine freedom of discussion reign than in America” (p. 244). Tocqueville

explained that freedom of thought and expression are not limited in the

United States as long as one remains within the boundaries that the majority

has erected. However, if one dares to cross these boundaries one is likely to

face a host of penalties and persecutions:

A political career is closed to him: he has offended the only power

that has the capacity to open it up. Everything is refused to him, even

glory. Before publishing his opinions, he believed he had partisans; it

seems to him that he no longer has any now that he has uncovered

himself to all; for those who blame him express themselves openly,

and those who think like him, without having his courage, keep silent

and move away. He yields, he finally bends under the effort of each

day and returns to silence as if he felt remorse for having spoken the

truth. (p. 244)

For Tocqueville, the most pressing problem with the democratic government

he witnessed in the United States is the omnipotence of the majority party

in relation to the minority. What he feared most, which he calls the

“tyranny of the majority,” is that the majority in the United States, because

it is so powerful, would easily deny both individuals and groups who are in

the minority their basic rights of expression and determination. As he puts it:

What I most reproach in democratic government, as it has been organized in the United States, is not, as many people in Europe claim, its

weakness, but on the contrary, its irresistible force. And what is most

repugnant to me in America is not the extreme freedom that reigns

there, it is the lack of a guarantee against tyranny. (p. 241)

Perhaps Tocqueville is exaggerating the power of the majority in the United

States to control public opinion, open discussion, and individual expression.

But it seems to me that it is difficult to disregard his argument that the

governing party in the United States together with the mass media go to

great length to squelch dissenting opinions and limit the discussion to those

parameters that they deem legitimate to talk about. Indeed, Edward Herman

and Noam Chomsky refer to the practice of shaping public opinion and

squelching dissent as “manufacturing consent.” Unlike the common view

14

THE MEANING AND VALUE OF DISSENT

that the media in the United States are independent and committed to

discovering and reporting the truth, Herman and Chomsky (1988) assert

that it is more accurate to say that the mainstream media tend to reflect the

world as powerful groups wish it to be perceived:

Leaders of the media claim that their news choices rest on unbiased

professional and objective criteria, and they have support for this

contention in the intellectual community. If, however, the powerful

are able to fix the premises of discourse, to decide what the general

populace is allowed to see, hear, and think about, and to “manage”

public opinion by regular propaganda campaigns, the standard view of

how the system works is at serious odds with reality (p. xi).

Much like Tocqueville, Herman and Chomsky are deeply concerned about

the way in which the powerful groups in this country use their influence to

control information, dominate public discussions, and suppress dissenting

viewpoints.

To illustrate this point, consider the case of the war in Iraq mentioned

above. In a speech given on October 7th 2003, Chomsky argues that

starting in September of 2002, there was an active propaganda campaign

initiated by the Bush Administration to scare the American public and

shape the conversation in such a way that made resistance to invading Iraq

unpopular and anti-American. To begin with, Chomsky (2003) reminds us

that in early September, National Security Advisor, Condoleezza Rice,

warned us that “the next evidence we were likely to have about Saddam

Hussein will be a mushroom cloud, presumably over New York.”2 Then on

February 5, 2003, Secretary of State, Colin Powell, delivered the famous

multimedia presentation at the U.N., using satellite images and intercepted

phone calls, to try to convince the world that Hussein was hiding weapons

of mass destruction and cultivating links with Al Qaeda. Finally, it has been

demonstrated by FAIR (Fairness and Accuracy In Reporting), the media

watch group, that in the months and weeks leading up to the invasion of

Iraq, ABC, CBS, NBC and PBS, conducted about 400 interviews with

experts about the war. In its study, FAIR concluded that Network newscasts

were dominated by current and former U.S. officials and largely excluded

Americans who were skeptical of or opposed to an invasion of Iraq. “Of all

393 sources,” the study found, “only three (less than 1 percent) were identified

with organized protests or anti-war groups.”3

Following this propaganda campaign, should it come as any surprise that

by the end of September of 2002, 60% of the American people regarded

Iraq as a serious threat to the security of the United States? Equally troubling, is that in the weeks leading up to the war, about 50% of the population

15

GORDON

believed that Iraq was involved in the September 11th attacks on the World

Trade Center and the Pentagon. For Chomsky, the irony is that at this same

time none of Iraq’s neighbors were afraid of Saddam, neither Kuwait, which

Hussein invaded, nor Iran, which experienced an eight-year devastating war

with Iraq. “They’re not afraid of him because they know exactly what the

U.S. intelligence and everyone else knows – Iraq was the weakest country

in the region” (2003). Its economy and population had been devastated by

the U.N. sanctions; the country was virtually disarmed and had been under

total surveillance for years.

What is at stake here is the ability of powerful groups in the United States,

including the administration and the mass media, to shape public opinion,

manufacture consent, and even induce individuals to give up thinking on

their own. Uncritical consent is very dangerous, as Tocqueville warned us,

since it undermines some of the core principles of a democratic society

such as individual expression, diversity of opinions, and open discussion.

In light of Chomsky’s critique, it is evident that uncritical consent among

members of congress, the mainstream press, and the American public made

it possible for the Bush administration to invade Iraq in 2003, despite

making a weak case for this war. In hindsight, one of the most important

lessons that we can learn from this war is about the critical role that dissent

can play in preventing unwarranted military confrontations.

DISSENT FROM SOCRATES TO ANGELA DAVIS

Based on the discussion above, it is clear that I think that dissent is

indispensable for the life of a democracy and that recent attempts to limit

dissent in the United States pose a serious threat to some of our core values.

Safeguarding dissent is essential for the welfare of a democracy because it

ensures that different and even opposing opinions will be considered before

taking action. Moreover, protecting dissent is vital since it guarantees that

unpopular viewpoints will be heard rather than silenced. According to this

view, arguments and disagreements are important because they force

people to think, search for evidence, and come up with convincing reasons

for their positions. In what follows, I would like to expand on the meaning

and value of dissent by looking at the lessons we can learn from the

examples of three famous dissidents: Socrates, Thoreau, and Angela Davis.

The story of Socrates as it appears in the dialogues of Plato indicates that

he loved to engage in dialogues with his fellow citizens from Athens.

Socrates was relentless in his search for the truth. He was an expert at

examining the opinions of his dialogue partners and evaluating them

from multiple perspectives to see if they hold up to the test of reason and

experience. Perhaps this is one of the reasons that the dialogues that

16

THE MEANING AND VALUE OF DISSENT

Socrates takes part in so often seem to go around in circles, analyzing the

same problem from different points of view, but never really reaching a

definitive answer. Yet while it is true that Socrates does not provide us with

conclusive definitions of virtue, justice, or love, he does help us gain a

better understanding of these very complex and rich concepts. As such,

Socrates embodies what it means to be a critical thinker: a person who

takes nothing for granted and continuously engages in the process of

questioning, doubting, analyzing, and revising his ideas.

One of the instances in which Socrates presents his views on dissent is in

the dialogue Gorgias. In this dialogue, Socrates engages in a discussion

with Gorgias, Polus and Callicles, all famous orators, on the differences

between the life of the orator and the life of the philosopher in the context

of debating the nature of the moral life. In one of the pivotal moments in

the dialogue, Socrates tells Callicles:

And yet for my part, my good man, I think that it’s better to have my

lyre or a chorus that I might lead out of tune and dissonant, and have

the vast majority of men disagree with me and contradict me, than to

be out of harmony with myself, to contradict myself, though I’m only

one person. (Plato, 1987, p. 52)

On the surface, the point that Socrates is making is that we should be

careful not to contradict ourselves, that is, that we need to be consistent and

logical in our arguments. More importantly, however, is the idea that it is

better to be true to oneself and uphold one’s values than to constantly change

one’s views so that one would remain popular and not offend others, even

though the majority of people might disagree with you.

In light of Socrates’ experience, we can see that dissent is frequently

related to critical thinking and the search for truth. This is not to say that

every dissident is a person who is committed to thinking and finding the

truth. Yet historically speaking, dissidents were more often than not people

who questioned popular beliefs and refused to take things for granted (e.g.

Galileo, Martin Luther King and Nelson Mandela). Moreover, for Socrates,

dissent implies a willingness to stand tough against popular beliefs and an

eagerness to defend the truth at all cost. In this view, dissent and disagreement are preferable to consent and conformity because the former are likely

to lead to a deeper understanding of complex issues like the nature of the

good life and whether or not the United States should have attacked Iraq.

Consent and conformity, on the other hand, have historically led people to

support misguided practices, unethical policies, and even criminal acts (the

Holocaust is a case in point)4.

17

GORDON

Another instance in which Socrates discusses dissent is when he is forced

to defend himself at his trial (Apology). One of the important arguments

that Socrates makes at his trial is that dissidents are valuable because they

often expose knowledge from which others can greatly benefit: “I think that

god put me on the state something like that, to wake you up and persuade

you and reproach you every one, as I keep settling on you everywhere all

day long” (Rouse, 1965, 436). Conformists, on the other hand, can deprive

the public of invaluable information and even tacitly support criminal acts.

Cass Sunstein (2003) summarizes this point well:

Conformists are often thought to be protective of social interests,

keeping quiet for the sake of the group. By contrast, dissenters tend to

be seen as selfish individualists, embarking on projects of their own.

But in an important sense, the opposite is closer to the truth. Much of

the time, dissenters benefit others, while conformists benefit themselves.

If people threaten to blow the whistle on wrongdoing or disclose facts

that contradict an emerging group consensus, they might well be

punished. Perhaps they will lose their jobs, face ostracism, or at least

have some difficult months. (p. 6)

Dissenters are important for democratic societies not only because they expose

various dangerous truths but also because they often speak out and struggle

against unjust laws and practices. Here, I think, the example of Henry

David Thoreau is instructive. In an introduction to a collection of Thoreau’s

writings, Joseph Wood Krutch notes that the slavery question drove Thoreau,

who in the earlier part of his life would have been inclined to withdraw

from society and immerse himself in nature, to fight against this grave

injustice: “To Thoreau, who cherished individual freedom as the most

precious of human rights, slavery could not but be the blackest of evils,

and so, in time, he was to find himself somewhat incongruously enrolled

among the defenders of the active abolitionists” (Thoreau, 1962, p. 13).

Indeed, in January of 1848, Thoreau delivered a lecture at the Concord

lyceum in which he preached complete, yet nonviolent resistance to any

authority which is unjust. Presumably, this lecture became the basis for his

famous essay “Civil Disobedience,” which was published the following

year. In this essay, Thoreau (1962) declared that respect for the law is evil

if it conflicts with respect for fundamental human rights such as freedom:

Unjust laws exist: shall we be content to obey them, or shall we

endeavor to amend them, and obey them until we have succeeded, or

shall we transgress them at once? Men generally, under such a

government as this, think that they ought to wait until they have

persuaded the majority to alter them. They think that, if they should

18

THE MEANING AND VALUE OF DISSENT

resist, the remedy would be worse than the evil. It makes it worse.

Why is it not more apt to anticipate and provide for reform? Why does

it not cherish its wise minority? Why does it cry and resist before it is

hurt? Why does it not encourage its citizens to be on the alert to point

out its faults, and do better than it would have them? (p. 92)

Here Thoreau clearly suggests that consent to the law of the land is not

always a good thing and that there are instances in which it is better to

transgress rather than follow unjust decrees. For Thoreau, the government

and the majority that support it are not inclined to correct the wrongs since

it would mean relinquishing some of their power and changing the status

quo. Therefore, it is up to the minority and ordinary citizens to call attention

to and struggle against those laws and practices, like slavery, that are

blatantly opposed to the basic principals of democracy. As Sunstein writes,

Diversity, openness, and dissent reveal actual and incipient problems.

They improve society’s pool of information and make it more likely

that serious issues will be addressed. I do not deny that great suffering

can be found in democracies as elsewhere. There is no guarantee,

from civil liberties alone, that such suffering will be minimized… But

at least it can be said that a society which permits dissent and does not

impose conformity is in a far better position to be aware of, and to

correct, serious social problems. (p. 149)

One dissident who dedicated her life to the struggle against the oppression

of African Americans in the United States is Angela Davis. Davis, a black

activist and member of the communist party, became famous during the

Civil Rights Era and the Vietnam War, as a vocal advocate of equality for

blacks and anti American imperialism. She continuously charged that African

Americans and other minorities were systematically discriminated against

and oppressed by institutions such as the judicial system in the United

States. Davis was arrested several times in large part because of her

involvement in the communist party as well as her vocal stance against the

United States’ treatment of blacks and its aggression in Southeast Asia.

Writing from jail in 1971 about the efforts of people such as Anthony Burns

and Marcus Garvey to emancipate Blacks, Davis (1971) notes that:

All these historical instances involving the overt violation of the laws

of the land converge around an unmistakable common denominator.

At stake has been the collective welfare and survival of a People.

There is a distinct and qualitative difference between breaking a law

for one’s own individual self-interest and violating it in the interests of

a class or a People whose oppression is expressed and particularized

19

GORDON

through that law. The former might be called criminal (though in many

instances he is a victim), but the latter, as a reformist or revolutionary,

is interested in universal social change. Captured, he or she is a

political prisoner. (p. 29)

Here Davis calls our attention to the difference between dissidents and

revolutionaries who break the law on behalf of a group of people who are

oppressed and unlawful acts committed by individuals to serve their own

self interest, such as robbers and murderers. The former are justified, she

implies, since political dissidents typically act for the sake of correcting

various institutional injustices and bringing about necessary social change.

The latter, on the other hand, may rightly be called criminals because they

are motivated simply by their own benefit and a desire to harm others.

Thus, the distinction between dissidents and criminals hinges on the different

goals that drive their respective decisions to break the law. Unlike regular

criminals, dissidents, according to Davis, are generally people who act in

order to resolve some grave injustice and bring about a better, more humane

and democratic society.

How would Socrates, Thoreau, and Davis respond to the U.S. invasion of

Iraq, mentioned at the beginning of this chapter? Socrates would probably

insist that this invasion was guided by erroneous information, a distortion

of the facts, and faulty reasoning. Based on his notion that dissidents should

be committed to searching for and speaking the truth, Socrates would urge

us to explore the real reasons that motivated the United States to attack

Iraq. Such an analysis would lead us to reject all of the justifications that

the Bush administration gave for its invasion like the notion that Saddam

was collecting weapons of mass destruction, that he intended to use these

weapons against the U.S. and its allies, and that he was cultivating links

with Al Qaeda. In short, a Socratic dissident would most likely come to the

conclusion that the invasion of Iraq should be strongly condemned since all

of the reasons that the United States’ government gave to justify its actions

were shown to be incorrect.

In addition to Socrates’ argument, Thoreau would probably say that even

if the United States had reliable and accurate intelligence prior to initiating

this war, the invasion was still unjustified since the United States was never

attacked by Iraq. Given that Thoreau believed that violence is only justified

as a last resort, like self defense, he would certainly never approve a preemptive, unprovoked invasion such as this one. For Thoreau, the United States’

invasion of Iraq was unjust not only because it was an unwarranted act of

violence, but also because the U.S. failed to follow the legal protocol that

exists in the U.N. regarding sanctions and the use of force. Inspired by

Thoreau, a dissident of the U.S. invasion would argue that the actions of the

20

THE MEANING AND VALUE OF DISSENT

United States were undemocratic because they infringed on the rights of the

Iraqi people and a sovereign country.

Angela Davis would agree with Socrates and Thoreau’s critique of the

actions of the Untied States against Iraq. She would probably add that the

U.S. invasion of Iraq was plainly not an act that was prompted by a noble goal

aimed at bringing about democracy to that country or establishing a more

humane society. On the contrary, Davis would most likely call the invasion a

criminal act motivated by self-interest, a lust for oil, and a desire for domination in the region. As a dissident who was deeply concerned about the

oppression of minorities in the United States, Davis would challenge the U.S.

invasion and occupation of Iraq because of the great suffering and destruction

it has brought about for the Iraqi people. She would point out that it is the

ordinary Iraqis, not Saddam or his family, who have paid the heaviest price

for this war in terms of lives lost and the loss of economic opportunities,

not to mention the psychological damage that this war has inflicted.

REASONABLE VERSUS THOUGHTLESS DISSENT

Although I have argued that dissent is generally a very valuable and even

indispensable practice in a democratic society, as a critique or defiance of

popular views, dissent should not be celebrated as such. As Sunstein argues,

in reality, dissent is not always helpful:

Sometimes dissenters lead people in bad directions. And when conformists are doing the right thing, there is far less need for dissent. If

scientists have reached the correct conclusions about global warming,

pseudo-scientists do us no favors in pushing nutty theories of their

own. (p. 7)

Global warming is a good example of an issue about which there is a fairly

broad consensus among scientists in the field. The majority of scientists

believe that global warming is serious, that it is getting worse, and that

something significant has to be done about it now in order to avert catastrophe

in the future. Still, there are a few scientists, business executives and some

prominent politicians in the United States who argue that global warming is

not really that serious and that we do not have enough evidence to support

the claims of the majority opinion. In this case, the dissent of the latter is

more like a refusal to face up to the devastating consequences of the warming

of the earth caused by the actions of human beings than an alternative

understanding of this problem that is worthy of our attention. It is an attempt

to put the short term financial gains of a relatively few individuals over the

long term welfare of the human race and the earth.

21

GORDON

The case of the war in Iraq discussed in this chapter is another example

in which the minority dissenters in the United States seem to be leading the

country toward a very dangerous outcome. Even though the majority of

Americans believed a couple of years ago that the United States should pull

its troops out of Iraq and end its occupation of this country as soon as

possible, the Bush administration decided in 2007 to send more American

soldiers into Iraq. Remember also that the decision of the Bush administration to support a surge of troops contradicts the recommendations of the

Iraq Study Group, which it appointed. Although the surge of American

troops in Iraq has had a substantial effect on reducing the amount of sectarian

violence, it has had little impact on making this country and the region in

general more secure. Much like the case of global warming, the insistence

of the Bush administration to maintain the U.S. troops in Iraq illustrates the

point that the opinions and actions of the minority dissenters do not always

lead to good results.

Moreover, there are many cases in which consent and consensus enable

people to live in peace and security in a democratic society. For instance,

Gary Shiffman (2002) notes that

There is a broad consensus that murder is a crime and should be

punished by the state. I believe that it risks little to add that in this

domain—the criminal code regarding acts of violence—consensus is

not only a fact but also a norm. That is, we consider it good and justified

that we agree; we believe, I think, that consensus on such matters is at

least an overlapping consensus, more likely the mark of civilization or

humanity. (p. 182)

For Shiffman, the consensus that exists in the United States and other

democracies that murder, theft, and other acts of violence are crimes that

should be punished is one of the virtues that distinguishes a civilized society

from other societies. Those who dissent and commit such crimes are not

simply breaking the law but are explicitly hurting other people and undermining the moral backbone of society.

Even though many dissenters throughout history have been people who

were motivated by just causes such as freedom and equality (e.g. Nelson

Mandela and Martin Luther King), there are also quite a few who can be

considered villains and monsters (e.g. Osama bin Laden and Hitler among

others). So what distinguishes the former dissidents from the latter? What is

the difference between Martin Luther King and Osama bin Laden, for

instance? To begin with, is the fact that the former was motivated by a very

noble cause, namely, ending the racism and discrimination of African

Americans in the United States and restoring the humanity of this oppressed

22

THE MEANING AND VALUE OF DISSENT

group of people. The latter, on the other hand, seems to be inspired more by

a lust for power and a desire for vengeance against the United States than

by some worthy causes such as justice or peace.

Second, is the point that the “good dissidents” mentioned above realized

that in order to bring about the ends they desired, they had to choose means

of struggle that were consistent with those ends. Both Nelson Mandela and

Martin Luther King elected to use nonviolent methods of resistance rather

than violence to combat the institutional racism and discrimination that

were rampant in their societies. Both Mandela and King realized that in

democracies the means of bringing about social change cannot really be

separated from the ends. They understood, in other words, the point that

Dewey (1966, pp. 81–99) made in Democracy and Education: that in

democratic societies the methods of initiating change have to be consistent

with and support the goals that one is seeking. In this view, using tyrannical

means to achieve democratic objectives is not only contradictory but also

counterproductive. In contrast, the “bad dissidents,” like bin Laden or Hitler,

advocated the use of violence, destruction and killing in order to bring about

their visions of a better world. Hence good dissidents typically diverge

from bad ones in both the ends they strive for and the means they select to

achieve these ends. The former embrace democratic values as guiding

principle for their actions, whereas the latter prefer despotic tactics to help

them achieve their plans and exploits.

What we need, then, is a form of dissent that is thoughtful and self-critical

rather than dissent for its own sake. In Sunstein’s words, “what we want to

encourage is not dissent as such but reasonable dissent, or dissent of the right

kind” (p. 91). Sunstein’s point is that a democratic society should encourage

open dissent for the sake of exposing problems or unjust laws, considering

multiple options, and carefully weighing all the evidence for each option

before taking action. In other words, dissent in democracies is valuable to

the extent that it can support the democratic process of freedom of speech,

exchange of ideas, deliberation and unbiased inquiry. It should not serve

as an uncritical defiance of an existing policy for the purpose of simply

rejecting it.

Paulo Freire (1994) echoes this point when he argues against a kind

of unreflective activism or “action for action’s sake” (p. 69). For Freire,

reflection and action as instruments of change in a democracy are mutually

dependent; action should always be informed by reflection and reflection

should always lead to action. In the same way, dissent, as a form of political

action intended to bring about change, ought to be thoughtful and intentional.

When Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on the bus in 1955, she wasn’t

merely tired or being stubborn. She was deliberately trying to resist a racist

23

GORDON

law of segregation, which required blacks to sit in the back of the bus and

give up their seats if there were white passengers standing. Park’s example

teaches us that thoughtful dissent is usually aimed at transforming some

significant social problem and trying to create a better and more humane

society.

Aside from the distinction between reasonable and unreasonable dissent,

we also need to consider how much dissent is optimal in a democratic

society. In other words, what is the best mix between consent and dissent?

Unfortunately, this question does not have an easy answer that can be applied

to all situations. Legally, it is probably best to permit free dissent, but

practically speaking, as I have shown, there are forms of dissent like murder

or hate speech that cannot be tolerated in a democracy. There are also

examples of dissent in the United States—like the refusal to face global

warming—that are not based on genuine reflection and a careful evaluation

of the evidence. At the same time, there are numerous cases of dissent, both

historical and current, that were not only reasonable, but that helped

transform this country for the better. Thus, each case of dissent needs to be

considered on its own merit.

Still, it is probably safe to say that this society suffers from too little

dissent rather than too much. How do I know that this is the case? For one

thing, the two party system of government in the United States makes it

very difficult for independent candidates with fresh perspectives to get

equal air time, not to mention get elected to office. Moreover, critics of

the American political system like Ralph Nader charge that, practically

speaking, there is very little difference between the Republican and Democratic parties since both of them are closely tied to the big corporations and

receive large donations from them. Historically speaking, the leaders of the

two major parties have rarely taken action that seriously challenged the

agendas of the large corporations, like fight for a national healthcare plan

or try to reduce our dependence on foreign oil. Analyzing the monopoly of

political elites in the United States in the context of public opinion and poll

taking, Justin Lewis (2001) concluded that

While the more centrist or conservative connotations of poll responses

inform public debate, many of the left-leaning, social democratic

inclinations suggested by opinion surveys—whether support for

universal healthcare, for increases in most forms of social spending, or

for limiting the power of large corporations—are generally ignored.

(p. 200)

Furthermore, the majority of the mainstream media in the United States

present the news in a very superficial, one-sided, and mundane way. There

24

THE MEANING AND VALUE OF DISSENT

are very few in-depth news programs in the big television networks and

even fewer debates among intellectuals about social, political or cultural

issues of interest. An atrocity in Africa or Asia gets much less attention

than the transgressions of celebrities in this country. Think of the amount of

coverage that the Anna Nicole Smith saga received in comparison to the

crisis in Darfur. The former is a story about an abused Playboy star that has

absolutely no political or social significance, whereas the latter deals with a

humanitarian disaster. It would seem that the mainstream media are much

more interested in getting the viewers to empathize with the misfortunes of

celebrities than to think deeply about important social issues or criticize the

policies of the administration.

Finally, public schools for the most part do not educate students to be

critical thinkers, respectful skeptics and reasonable dissidents. Rather, these

institutions teach students to accept the information that is given them

without questions, to look for simplistic solutions to complex problems, and

to adjust to the status quo. Kathleen Vail (2002) confirms this sentiment

when she writes that “some civics and social studies educators worry that

by emphasizing the easy side of patriotism, schools are neglecting to show

their students the complex and difficult sides of democracy, including of

government in their lives” (pp. 14–15). Vail goes on to suggest that there

seems to be a vacuum of education about democracy in our schools. The

four chapters in the second part of this book attempt to respond to this void

by examining the role of dissent in the education of democratic citizens and

exploring ways of helping students become critical citizens and thoughtful

dissidents.

CONCLUSION

Despite the various dangers of uncritical dissent discussed above, I strongly

agree with the statement of the former president of Uruguay, Lacalle, that

“consensus destroys democracy,” cited at the opening of this chapter.

Consensus destroys democracy by greatly curtailing the possibility that

diverse viewpoints, rigorous discussion and critique—all essential to maintain

the democratic process—will play a major role in shaping the direction of

the country. And consensus destroys democracy by privileging the majority

opinion, ignoring the needs and interests of minorities, and marginalizing

the voices of dissent. Ultimately, a society that punishes dissenters for

speaking out against a wide range of institutional forms of discrimination,

inequalities, and racism cannot be considered democratic.

Gary Shiffman echoes this point when he writes that “regimes that purport

to represent the people on the basis of perennial and perpetual consensus

are generally, and I believe rightly, viewed as undemocratic, or as fake

25

GORDON

democracies. Democracy without institutionalized, normative disagreement is

simply not democracy” (p. 182). Open dissent is thus one of the essential

characteristics that distinguish a democratic society from other societies

that are despotic in nature. Indeed, freedom as one of the foundational pillars

of a democracy is an empty phrase unless it includes the ability to dissent

and disagree with the opinions of others. Without the ability to dissent a

society cannot really be considered free. Neither is such a society truly

diverse, in the sense of being open to multiple perspectives and beliefs.

NOTES

1

2

3

4

See for instance an article in The Washington Post from August 12, 2004 in which the writer

admitted that from August 2002 until March 19, 2003 the Post ran more than 140 front page stories

that focused heavily on administration rhetoric against Iraq and downplayed critics of the Iraq war.

See also the September 8, 2002 article in The New York Times by Michael Gordon and Judith Miller

entitled “U.S. Says Hussein Intensified Quest for A-Bomb Parts” in which the authors suggest that

Saddam Hussein is renewing his efforts to obtain weapons of mass destruction and downplay the

evidence that cast considerable doubts on this claim.

Taken from a speech that Chomsky gave at Illinois State University on October 7th, 2003 entitled

“Hegemony or Survival: America’s Quest for Global Dominance.” Retrieved 12/6/06 from http://www.

democracynow.org/article.pl?sid=03/10/22/1450216&mode=thread&tid=25.

See the Action Alert by FAIR entitled “In Iraq Crisis, Networks Are Megaphones for Official

Views.” Retrieved 12/6/06 from http://www.fair.org/index.php?page=1628

For a good discussion of the dangers of conformity in the context of the Holocaust see Hannah

Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, (New York: Penguin Books,

1977); see also Geoffrey Short’s essay “Antiracist Education and Moral Behaviour: Lessons from

the Holocaust,” Journal of Moral Education, 28, 1999, 49–62.

REFERENCES

Arendt, A. (1977). Eichmann in Jerusalem: A report on the banality of evil. New York: Penguin Books.

Davis, A. (1971). If they come in the morning: Voices of resistance. London: Orbach and Chambers.

Dewey, J. (1966). Democracy and education. New York: The Free Press.

Freire, P. (1994). Pedagogy of the oppressed (Myra Bergman Ramos, Trans.). New York: Continuum.

Herman, E. S., & Chomsky, N. (1988). Manufacturing consent: The political economy of the mass

media. New York: Pantheon Books.

Lewis, J. (2001). Constructing public opinion: How political elites do what they like and why we seem

to go along with it. New York: Columbia University Press.

Plato. (1987). Gorgias (D. J. Zeyl, Trans.). Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing company.

Rouse, W. H. D. (1956). Great dialogues of Plato. New York: New American Library.

Shiffman, G. (2002). Construing disagreement: Consensus and invective in ‘Constitutional’ debate.

Political Theory, 30(2), 175–203.

Short, G. (1999). Antiracist education and moral behaviour: Lessons from the Holocaust. Journal of

Moral Education, 28, 49–62.

Sunstein, C. R. (2003). Why societies need dissent. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Thoreau, H. D. (1962). Thoreau: Walden and other writings (Joseph Wood Krutch, Ed. & Intro.).

New York: Bantam Books.

Tocqueville, Alexis De. (2000). Democracy in America (H. C. Mansfield & D. Winthrop, Trans. &

Ed.). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Vail, K. (2002). Lessons in democracy. American School Board Journal, 189(1), 14–19.

26

SEAN P. DUFFY

HISTORICAL, POLITICAL, AND LEGAL EFFORTS

TO SQUASH DISSENT IN THE UNITED STATES

“Political repression [is] not episodic and cyclical… but rather at the

center of the national experience.”

William Preston, Jr. (Preston, 1994, p. 279)

William Preston first published his seminal work linking the suppression of

dissent with fundamental strains of anti-radicalism and xenophobia in 1963,

immediately in the wake of what was at the time the nation’s latest bout of

extreme political and legal efforts to squash dissent. In profiling the antiradicalism of an earlier time (1880–1920), Preston established what he

believed to be a constant factor in American political history: the impulse

to suppress the extremes of civic discourse in the name of protecting

democracy. Following Preston, I will be using the notion of “anti-radicalism”

throughout this chapter to refer to the efforts to control and censor individuals or groups that attempted to speak out and dissent against the actions

of the government. Preston’s lessons are no less important to us nearly fifty

years later, as the patterns he described are clearly visible in American

national life 100 years after the period he studied. This chapter will outline

the fundamental factors in American civic culture that Preston identified,

then detail several historical “high points” of the emergence of these factors

into civic life, and conclude with an examination of the different tools

government – at the local, state, and federal levels – has historically used to

suppress dissent.

ANTI-RADICALISM IN AMERICAN CIVIC CULTURE

From the earliest days of the American Republic, dissent has been associated

with radicalism, which in turn has been seen as a threat to the republic. The

suppression of dissent has ebbed and flowed with anti-radicalism and

nativist—anti-foreigner or anti-immigrant—sentiments. These factors have

often been augmented by domestic economic difficulty or the involvement

of the United States in foreign conflict. Jules Boykoff (2007), in his work

detailing the complicity of government, the media and popular culture in

the suppression of dissent, places this suppression in the context of the

M. Gordon (ed.), Reclaiming Dissent: Civics Education for the 21st Century, 27–48.

© 2009 Sense Publishers. All rights reserved.

DUFFY

classic tradeoff between freedom and security: “The state, in concert with

the mass media, delimits what are considered ‘appropriate’ words and

deeds during ‘exceptional’ moments when state action is ostensibly needed

to install order” (p. 17). The association of disorder with radicalism of a

foreign origin often results in local, and ultimately federal, anti-immigrant

efforts including the denial of legal rights (such as the habeas corpus right,

the right to legal representation, and the right to appeal) and the use of

deportation. This focus on the immigrant is partly cultural and partly legal.

On the one hand, American culture is characterized by a xenophobia that so

easily associates radicalism with ‘un-Americanism’ and the foreigner. On the

other hand, the constitutional rights of non citizens are ambiguous, and

therefore the easiest to target through legislation and executive action.