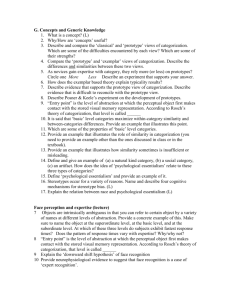

Work Group Diversity and Group Performance: An Integrative Model

advertisement