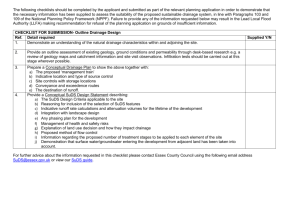

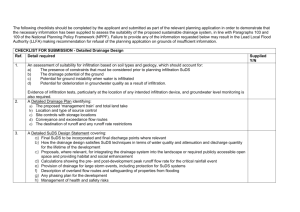

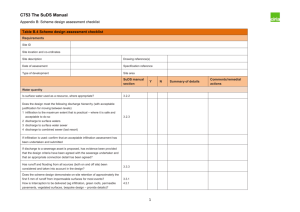

Interim Code of Practice for Sustainable Drainage Systems

advertisement