© Spend Matters. All rights reserved.

1

Putting the “Supply” in Supply Networks

2

Part 2: Tackling the Multi-Tier Information Problem in the Inbound Supply Chain

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

In Part 1 of this two-part research report, we examined the complexity of managing supply in a multi-tier

supply network. We also discussed a framework to help supply management professionals put a new form of

“supply management” at the heart of the supply chain, with a particular focus on advanced supply planning

and execution of raw materials (rather than just provisioning any type of enterprise resource). The idea is not

to rename (or advocate on behalf of) the direct procurement organization, but rather to look at multi-tier

supply management as an end-to-end process that requires cross-functional and cross-enterprise

collaboration – and the tools needed to support that process.

Most firms are thinking too linearly about the role of procurement, as a silo, to find low-cost sources of

supply without really explaining that all suppliers could provide better part-level performance on a

broader/balanced supply scorecard – if the supply chain were managed more holistically and orchestrated

better. Suppliers don’t enjoy expediting any more than brand owners do. They don’t make more money reinspecting things as specifications change. They certainly don’t make more money working a third shift.

Procurement knows all of this, but doesn’t have the mandate to orchestrate the end-to-end supply chain –

and firms historically haven’t had the tools.

The real issue here is that jobs must change from functional, single-tier, hierarchical, transactional, symptombased process management to horizontal, multi-tier, collaborative and outcome-based process views focused

on profitably serving the customer. We need fewer clerks and planners and more procurement supply

managers who own the end-to-end flow of supply from negotiation of the supplier’s technology road map to

the product shipment out of the factory. That includes the price, delivery, use, quality and continuity of

supply. We also need fewer silo specialists and more customer-focused generalists who have the full

panoramic view of the process and the authority to make real-time decisions.

In this second installment, we will dive into the details of this multi-tier information problem that needs to be

solved to deliver the above – and we’ll evaluate the pros and cons of various approaches to solve it.

1

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

1

2

3

4

5

© Spend Matters. All rights reserved.

Multi-Tier Supply Management Is the Biggest Differentiator of Supply

Management Performance

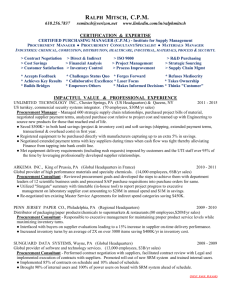

When Spend Matters conducted a research study last year on the extent to which direct procurement

organizations were driving broader supply management impact across the supply chain, we found that there

were sizeable gaps between the capabilities of the top performers (measured across a “balanced scorecard”

of supply performance metrics) across the board. But the biggest gaps were in areas that were multi-tier in

nature (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Supply Management 2.0 Capabilities Drive Increased Supply Performance

Top"Supply"Performers"

Peers"

% Gap

Supply"base"segmentaIon"to"drive"category"

management,"supplier"management,"risk/regulatory,"

InnovaIon"support"(e.g.,"early"supplier"involvement;"

make"vs."buy;"crowdsourcing;"etc.)"

53%

31%

Integrated"supply"performance"management""

46%

VMI"support"(e.g.,"JIT"Warehouses,"inventory"visibility,"

etc.)"

MulI+Ier"raw"material"inventory"posiIoning"(including"

at"suppliers)"

52%

MulI+Ier"cost"modeling,"forecasIng,"and"intelligence"

61%

Dynamic"supply"allocaIons"based"on"supplier"rebates,"

penalIes,"capacity,"lead"Imes,"etc."

TranslaIon"of"S&OP"to"a"mulI+Ier"collaboraIve"supply"

plan"

Supply"risk"modeling"/"monitoring"(e.g.,"“heat"maps”,"

external"intelligence"integraIon)"

Performing"“buy+sell”"to"buy"on"behalf"of"smaller"

suppliers"

56%

Tax+advantaged’"supply"strategies"

46%

51%

48%

85%

62%

0"

1"

2"

3"

4"

5"

Weak/ Ad Hoc

Fair

Good

Very Good

Excellent

Source: “Direct Procurement Excellence Study,” Institute for Supply Management and Spend Matters, 2013

For example, supply risk monitoring, which tends to be multi-tier in scope for critical suppliers, showed the

largest gap at 85 percent (i.e., top performers had an 85 percent greater capability score than their peers).

The gap was 62 percent (the second greatest gap) for multi-tier sourcing/supplier relationship management

(SRM) programs called “Buy-Sell.” For multi-tier cost management, the gap was 61 percent (the third largest

gap). Multi-tier inventory positioning had a 51 percent gap. You get the idea.

These multi-tier processes are challenging in terms of process and multi-firm collaboration, but it’s even

more challenging from an information management perspective. Basically, an information model that

2

6

7

8

9

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

© Spend Matters. All rights reserved.

captures the complex, multi-tier, “many-to-many” relationships in the physical supply network is required.

The information architecture for the supply chain is as strategic as the “business architecture” (i.e., your

operating model in terms of process/organization/governance), especially given the convergence happening

with “The Internet of Things.”

The bottom line is that your supply network is not a commodity. So, don’t treat your procurement and supply

chain information platforms like commodities (e.g., like ERP). You need a set of core information platforms

that will provide an information capability that is as robust and agile as the supply network you are trying to

run and improve. The word “platform” is overused; what we mean is not any one single technology

application, but rather a sophisticated data model (and supporting data stores – whether in the cloud or

behind the firewall) that supports the complex process models inherent in a multi-tier supply network.

So, how are manufacturers building this capability? There are essentially two choices:

•

•

The first approach subscribes to the sunk cost fallacy and aims to “use what you got.” This is a

preference for myopic CIOs who hope to use the data model and data stores from a single-tier

ERP/SCM/procurement application already in place. The hope is to wait for an ERP provider to retool

its fundamental product architectures (i.e., the data models themselves, not the type of database

they run on) at a cadence as fast as their supply chains.

The second approach is to use a network-based data model suited to the complexity of the multifirm processes in question. As the supply chain-centric public marketplaces morphed a decade ago

to private “supply chain business [information] networks,”1 the “system of process” (or “system of

engagement”) moved into the cloud and began to offer up collaboration functionality previously

locked up inside the single-tier applications, but all the while integrating to and persisting both

master data and core workflow data behind the firewall as needed. This mix of public and private

cloud is called a “hybrid cloud deployment model.”

You can probably guess which option the more progressive firms with complex multi-tier supply chains are

taking.

The "Multi- Multi" World of a Supply Chain Business Network

Let’s get this out of the way: Traditional enterprise applications and application architectures are dying.

Management of a factory-centric supply chain has given way to orchestration of a trading network, which

operates very differently. Weekly materials requirements planning (MRP) runs, and associated batches of PO

lines, won’t cut it. Neither will weekly payment runs. The former bloats lead times and inventories while the

latter hampers on-time payments and early payment discounts. Proliferating spreadsheets are a clear analog

to proliferating inventory you can’t optimize. Data duplication/replication across partner systems is akin to

excess and obsolete (E&O) inventory – immediately stale and a drag on performance. If you believe that

“inventory = waste,” then such proliferated data is toxic waste.

More strategically, those who have quicker access to better information deeper in their upstream supply

network will be able to commit with confidence to customers, stakeholders and investors. They will outsell

you, they will out-profit you, and they will see where their 5 Cs (cost, capacity, constraints, capabilities and

contracts) need shoring up in order to gain and preserve competitive advantage. The visibility brings control

in execution to “keep your promises” (which is ultimately what supply chain is all about). It also brings insight

into new and better potential promises you can make that nobody else can. Even just within a basic S&OP

process, demand must be received and translated rapidly. It must be matched with granular, constrained

supply, for inventory, capacity and logistics – and that view of supply must be extended seamlessly into the

upstream supply tiers.

1

In Part 1 of this two-part series, we mentioned that we would adopt the popular term “supply chain business network” to mean a supply information network

that supports the physical supply network (i.e., the “information” aspect is implicit). A supply chain business network is merely a supply chain-specific

business network that is different from B2C social networks, B2C/B2B commerce networks like Amazon/AmazonSupply, or B2B commerce networks like Ariba.

3

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

© Spend Matters. All rights reserved.

This information advantage brings us to the “multi-multi” discussion of how your information architecture will

need to accommodate the following “multis” in the supply network.

Multi-Tier: What You Can’t See Will Hurt You

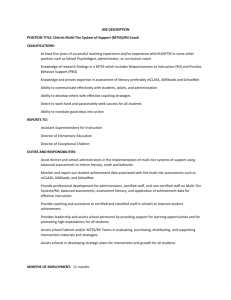

Multi-tier is not a new concept. Many companies conduct multi-tier network mapping analysis such as

supplier risk analysis on critical tier n suppliers. Others manage key supplier tooling (and related capacity

planning processed as their own). Some larger firms in the high-tech sector do some form of “buy-sell”

program to buy goods from tier 2 suppliers to supply their tier 1 suppliers such as contract manufacturers

(also popular for large metals buyers in the automotive and aerospace and defense industries). Others do

multi-tier order management with purchased finished goods into a retail channel. A rarified few might even

do multistage inventory positioning and optimization of raw materials into just-in-time (JIT) warehouses and

other supplier locations. But for many firms, these strategies need to be performed in unison (as was shown

in our direct procurement research and shown in figure 2). Unfortunately, these requirements are often

supported using homegrown, customized, and/or one-off applications that don’t integrate well to each other,

to supplier systems, and to existing ERP/SCM applications.

Figure 2: The “Multi- Multi” Problem: There Are Multiple Types of Multi-Tier Concerns

Type(of(mul$%$er(problem(concern((

(%*of*responses*–*mul8ple*responses*allowed)*

• Procurement*is*more*

concerned*with*cost*visibility*

and*risk*visibility*

Other(

7%(

Mul$%$er(

order(

management(

and(visibility(

18%(

Mul$%$er(

supply(

planning(

18%(

Mul$%$er(cost(

visibility(

25%(

Mul$%$er(risk((

32%(

• Supply*chain*is*more*

concerned*with*mul898er*

supply*planning*and*execu8on*

(e.g.*High*Tech*industry)*

• This*problem*was*cited*by*the*

more*advanced*firms*(i.e.,*

“you*don’t*know*what*you*

don’t*know”)*

Multi-demand: Scenarios, Signals, and Variability

Terms like supply chain “resiliency,” “agility” and “flexibility” are certainly popular. But they can mean

different things. On the supply side, these terms usually relate to the systematic ability to manage supply risk

for critical parts and suppliers up through a few tiers – via better prediction (e.g., earlier) and better (e.g.,

faster) recovery. For others, these terms are associated with mitigating commodity purchase price risk

through hedging or smoothing strategies. For the truly advanced, these terms apply to translating strategic

business scenarios (e.g., mergers and acquisitions [M&A], re-shoring, outsourcing) and supply scenarios via

what-if analyses on top of extended supply network models.

But let’s start simple. Assume a fixed supply network, with scenarios only having an impact on demand

volumes. How should you best manage the demand volatility? You can try to shape it as best you can (and

cut down supply lead times of course), but you’ll only get forecast accuracy to improve so far – it’s like

pushing a boulder uphill. However, just lumping all the fine-grained forecasts using advanced tools in the

“omni-channels” to a point forecast that is then translating to upstream supply planning via S&OP creates

information loss around those signals. Rather, passing back the consensus demand plan and the demand

4

8

9

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

1

2

© Spend Matters. All rights reserved.

variability allows you to collaborate with upstream internal/external suppliers to manage this variability (e.g.,

better rough-cut capacity/inventory planning, flexible upside contracts, use of party with lowest risk

treatment costs). It varies in the product life cycle, so you have to dynamically reconfigure the same network

(e.g., point of postponement, transportation mode) as variability changes.

This art and science of translation is not just a single-step one-size-fits-all approach. Rather, it requires

ongoing segmentation with different variables, and they must all integrate both vertically through

organizational hierarchies/matrices as well as horizontally across the network tiers.

Multi-Segment … Interleaved and Concurrent (Think “Omni-Channel Supply”)

Experienced supply chain practitioners know that segmentation is by no means a new idea, but it’s never

been more important, or more complex. From a supply perspective, you can start at the consumer level and

think of segments as natural clusters of customer choices based on their “balanced scorecard of supply” (i.e.,

quality versus cost versus availability and so on). These segmentations generally work their way up the supply

network through segmented transportation modes, warehouse zone, manufacturing cells, purchasing

categories and supplier types up through multiple tiers. However, rather than just single or simplistic

segmentations inherited from downstream demand channels, advanced firms are using concurrent granular

multivariate segmentations to mass customize their material flows and information flows by interrelated

supply-side attributes such as commodity type, risk type, supplier type, buyer/seller dependency, regulations

in force, availability of substitutes, profit-at-risk, and many others. Such complex “omni-channel supply”

reduces one-size-fits-all process design, but also requires IT systems that can orchestrate (not just analyze)

such workflows.

Segmentation is not just an analytic exercise. If you can standardize some of your data, KPI categories,

processes, and roles, then you have the ability to translate not just a planning/performance management

view from a customer/channel view to supply network view back to a supply/spend category view, and then

down to supplier/part/location level in a business unit supply chain, but you can actually cross the

planning/execution domains and the previously fragmented topology of legacy applications in each of those

areas. This is heady stuff I know, but you’re starting to see early hints of it coming together, but only with

multi-tier native functionality built into platforms/networks. What it allows is the automation or rapid demand

and supply translation compression and making the feedback loops immediately visible. It also allows you to

see the effect of a decision before and during its implementation, not afterwards through an analytical

autopsy.

Seamless Multi-Period and Multidirectional Into the Frozen Zone – It’s All About the Commitment

Just as demand signals are translated to supply across tiers, the same can be said about the translation

across time. As the planning horizon moves from years and months down to weeks, going from

unconstrained supply scenarios to constrained plans (and the feedback loop to reshape demand if needed),

and from promised to committed (including both contractual commitments in strategic sourcing and actual

tactical “commits” as we enter the “frozen zones”), the linkages between contracts and supply plans must be

tight. “Strategic sourcing” for indirect spending is often a misnomer, and after the contract is signed, the

matching of invoices against price/terms/SLAs is about the extent of the integration (which itself is by no

means guaranteed – especially in complex spend such as transportation contracts). In the supply chain, the

stakes are much higher. Like the adage about the farm where “the cow is involved, but the pig is committed,”

indirect spend can be milked for savings, but direct spend is where you can get truly slaughtered – especially

if there are contract penalties (for volume commitments and for on-time deliveries to dock doors at retailer

DCs) and rewards (i.e., discounts and rebates). Commitments matter! For example:

•

The “commits” serve as the dynamically confirmed contracts – and they should be determined

by an intelligent and dynamic sourcing process that performs supplier quantity allocations and

reserves critical upside capacity. HP’s well-known “Procurement Risk Management” methodology

lives here in the contract realm between pricing, volumes/variability, and capacity. Firms don’t have

to apply this level of rigor, but there should at least be a process here to ensure rough-cut flex

5

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

© Spend Matters. All rights reserved.

•

•

•

capacity exists at a supplier – or set of suppliers. Allocating volume between suppliers shouldn’t rely

on some fixed allocation percentage or crude heuristic, but should be made on multiple criteria

based on supplier performance, hedging criteria (e.g., currency – not just commodity volatility), price

versus lead-time/lot-size, and other criteria. Allocations in supply planning must get smarter!

The commit process is the hinge between planning and execution where downstream POs,

acknowledgements, ASNs, and more can take over without incident. The ability not only to superconduct the demand signals up the network, but also do the same with supply commitments back

down, allows firms to gain resiliency through proactive identification of issues (early enough to do

something about it) rather than just focusing on recovery (e.g., firefighting, expediting).

While “commits” seem to just focus on perfect order fulfillment of materials, commitments must

also be made by third-party logistics (3PL) providers and other process participants who

provision any type of critical resources. For example, consider the spend category and business

process known as transportation (e.g., truckload). Complex bid optimization in strategic sourcing

must dovetail into the transportation management systems (TMS) where execution occurs. If they

don’t, contract compliance rates can easily plummet to under 50 percent. Other resources include

work crews of contingent laborers, shipping ports, critical equipment, and even money itself in the

area of trade finance (see SpendMatters/tfmatters for more information on this broad topic).

“Commits” have commercial implications, but also are fundamental to performance

management and relationship management. The whole notion of translating, propagating, and

matching supply/demand from planning to commitment/execution is very powerful because you are

in essence turning “strategy deployment” (often called hoshin planning) 90 degrees from a top-down

cascading of scorecards to an organizational hierarchy to a horizontal translation across the tiers.

This aligns the metrics of the process participants (e.g., EVP SCM; CPO; commodity managers,

supplier managers, supply planners, contract managers, suppliers) and is what we call “supply

performance management”. Get it right and you inherently tear down the silos and your network will

hum. Get it wrong and the friction will start to build.

“Multi- Multi” Information Infrastructure for a Many-to-Many Supply Network

If you want to get the above right, there’s obviously a lot of orchestration required. You definitely will need

solid technology to help. Real “collaborative commerce” in the supply chain requires rich and dynamic highspeed orchestration. Batch MRP runs, acting on stale data, and augmented by spreadsheets, provides little

help in dynamic supply-demand matching. But the complexity to orchestrate activities (and the risks that

threaten those activities) though a “many-to-many” data model that captures the complex interrelationships

of facilities, products, partners, lanes, equipment, people, plans, time periods, contracts, geospatial

information and more is “non-trivial.” So, in this final section, we will highlight the following technology

“multis” to consider beyond the usual requirements of multicurrency, multilingual, multi-organization, and so

on.

Multi-Role: A User-Friendly CIA

The acronym “CIA” in information security parlance means confidentiality, integrity and availability. Role-based

permissions, transparent rule management, and fail-safe infrastructure deployed in a hybrid cloud

deployment model are going to become standard fare. Multi-device user interfaces should be tuned to the

task: tabular planning; color-coded dashboards; graphical network models (and business process models for

documents orchestration); and composite workbenches must augment traditional web forms. This isn’t just a

technical issue for, say, masking price data from the wrong users, however. It can be used as a weapon. For

example, can you show an individual customer their upstream supply chain that is being managed by you

and your partners? Can you filter your entire inbound supply chain information that is pegged to a customer?

That capability would inspire confidence in customers, no?

Multi-Partner Integration: Mass Customizing the Information and Interfaces

B2B integration is complicated enough, so it shouldn’t be needlessly overburdened with point-to-point handbuilt adapters, nor burdened by ill-fitting commercial models (e.g., supplier networks that charge suppliers a

6

8

9

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

1

2

3

4

5

© Spend Matters. All rights reserved.

percentage of the value of the goods). More sophisticated networks not only offer a choice of integrations to

trading partners via web forms, spreadsheets or machine-to-machine B2B connectivity, they also provide

“mass customized mappings” (e.g., e2Open’s “map factories” that help trading partners map their preferred

protocols to the OAGIS standard is a good example).

Increasingly, we expect to see more integration to third-party content/apps/devices while also employing

rules-based orchestration and even machine learning to help automatically resolve problems rather than just

being alerted to them.

Multi-Analytics: Big Analyses to Go Along With Big Data

Increasingly, information networks are generating network-derived insights to inform process participants of

potential threats (e.g., supply chain risk analytics) and rewards (e.g., aggregated cost/price benchmarking or

recommended supply network changes). With the increasing telemetry data from sensors across the supply

chain, and the power of predictive analytics and prescriptive analytics (e.g., optimization), the opportunities

are boundless2.

Looking Forward: From Information Networks to Platforms

Advanced information networks that provide a “single source of truth,” rather than just being simple

document exchange between two parties, is clearly the future in the supply chain. We believe strongly that

information networks also will evolve to Platforms as a Service (PaaS) similar to Salesforce’s Salesforce1

platform in the customer relationship management (CRM) world. A PaaS of this type in the procurement and

supply chain would allow an ecosystem of partners to develop complementary apps and other services that

would extend and enhance the network.

As supply chain process participants become increasingly sophisticated “prosumers” of information, they’re

going to need to fundamentally upgrade their capabilities to move from an enterprise-class application

approach focused on the internal supply chain to a network-based architecture focused on orchestrating the

end-to-end demand-driven supply network.

To be clear, the choices between traditional enterprise-class cloud applications (i.e., multi-tenant but

designed for a single-tier enterprise scope) and network-based cloud applications and services (i.e., support

multi-tier value networks) are not mutually exclusive. There is plenty of work to perform selective upgrades,

to standardize data, to consolidate application instances, and more. But this is only rearranging and polishing

the deck chairs on a leaky boat not suited for the increasingly stormy seas in the global economy.

Manufacturers should definitely begin to explore some of the advantages that supply chain business

networks have to offer. There are great case studies from many firms, and the good news is that you can start

incrementally within your supply chain to deliver quick-hit successes and start the cycles of self-funded

scope expansion.

Firms that start this journey now can find ample reward in the more advanced scenarios we’ve spelled out in

this research report. Firms that forego the rewards by not making a choice are in fact still choosing – and that

choice likely will lead to those organization being increasingly noncompetitive.

In this case, “postponement” is not a best practice.

2

For more information on supply analytics, see “Supply Analytics: an Overlooked Opportunity,” Supply Chain Management Review, July 2012.

7