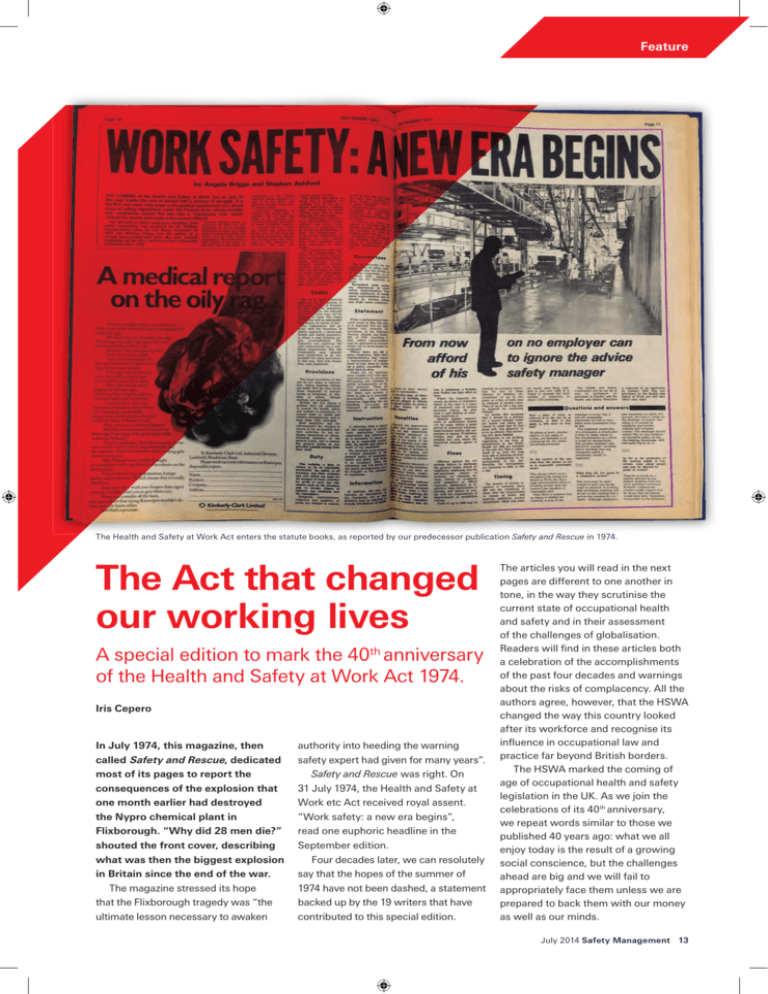

The Act that changed our working lives

advertisement