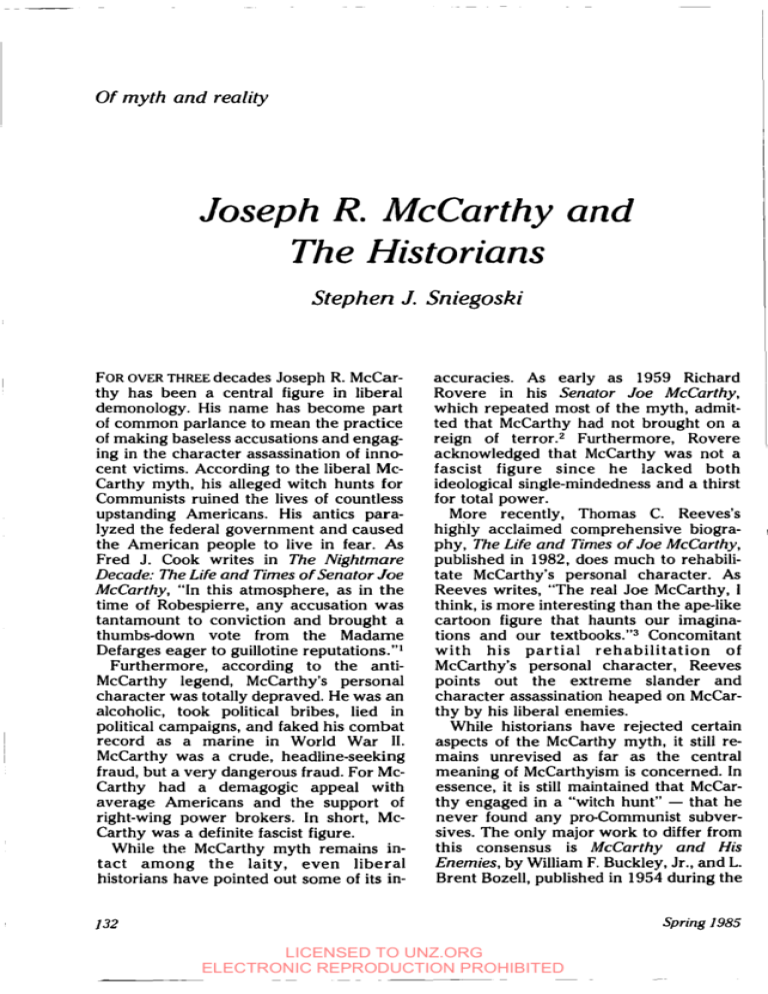

Joseph R. McCarthy and The Historians

advertisement

~ ~ _ _ _ _ ~ Of myth and reality Joseph R. McCarthy and The Historians Stephen J. Sniegoski I ~ I FOROVER THREE decades Joseph R. McCarthy has been a central figure in liberal demonology. His name has become part of common parlance to mean the practice of making baseless accusations and engaging in the character assassination of innocent victims. According to the liberal McCarthy myth, his alleged witch hunts for Communists ruined the lives of countless upstanding Americans. His antics paralyzed the federal government and caused the American people to live in fear. As Fred J. Cook writes in The Nightmare Decade: The Life and Times o f Senator Joe McCarthy, “In this atmosphere, as in the time of Robespierre, any accusation was tantamount to conviction and brought a thumbs-down vote from the Madame Defarges eager to guillotine reputations.”’ Furthermore, according to the antiMcCarthy legend, McCarthy’s personal character was totally depraved. He was an alcoholic, took political bribes, lied in political campaigns, and faked his combat record as a marine in World War 11. McCarthy was a crude, headline-seeking fraud, but a very dangerous fraud. For McCarthy had a demagogic appeal with average Americans and the support of right-wing power brokers. In short, McCarthy was a definite fascist figure. While the McCarthy myth remains intact among the laity, even liberal historians have pointed out some of its in- accuracies. As early as 1959 Richard Rovere in his Senator Joe McCarthy, which repeated most of the myth, admitted that McCarthy had not brought on a reign of terror.2 Furthermore, Rovere acknowledged that McCarthy was not a fascist figure since he lacked both ideological single-mindednessand a thirst for total power. More recently, Thomas C. Reeves’s highly acclaimed comprehensive biography, The Life and Times of Joe McCarthy, published in 1982, does much to rehabilitate McCarthy’s personal character. As Reeves writes, “The real Joe McCarthy, I think, is more interesting than the ape-like cartoon figure that haunts our imaginations and our textbook^."^ Concomitant with his partial rehabilitation of McCarthy’s personal character, Reeves points out the extreme slander and character assassination heaped on McCarthy by his liberal enemies. While historians have rejected certain aspects of the McCarthy myth, it still remains unrevised as far as the central meaning of McCarthyism is concerned. In essence, it is still maintained that McCarthy engaged in a “witch hunt” - that he never found any pro-Communist subversives. The only major work to differ from this consensus is McCarthy and His Enemies, by William F. Buckley, Jr., and L. Brent Bozell, published in 1954 during the Spring 1985 132 LICENSED TO UNZ.ORG ELECTRONIC REPRODUCTION PROHIBITED McCarthy p e r i ~ d .Referred ~ to by Willmoore Kendall as “the book no liberal reads,’I5 Buckley and Bozell’s book makes a strong case in defense of McCarthy; but the work is usually shrugged off by historians as a contemporary right-wing apologetic. Among the standard histories of McCarthyism, the only difference is between what might be called liberal and leftist accounts. To generalize, liberal accounts do not rule out completely the existence of pro-Communist subversives and the need to root them out. But they assume that the number of these subversives was small and that the executive branch was successfully taking care of them. Leftist versions, on the other hand, attack the federal government’s loyalty-security program. They deny the existence (or even the concept) of loyalty-security risks. It is implied that even if there were proCommunists in the federal government, they should not have been removed from their positions. McCarthyism, according to the leftist view, was but the logical extension of Truman Cold War anticommunism. In the liberal category would fall such works as Richard Rovere’s Senator Joe McCarthy and, with a tinge of the leftist viewpoint, Thomas Reeves’s The LiFe and Times of Joe McCarthy. On the right flank of the liberal accounts are When Euen Angels Wept: The Senator Joseph McCarthy Affair-A Story Without A Hero, by Lately Thomas (pseudonym for Robert V. Stee1e)‘j and The Communist Controversy in Washington:From the New Deal to McCarthy, by Earl Latham.7Both these works imply a laxity in the federal government’s enforcement of its loyalty-security regulations but deny that McCarthy uncovered any subversives. Robert Criffith’s The Politics o f Fear: Joseph R. McCarthy and the Senates and Fred J. Cook’s The Nightmare Decade: The Life and Times o f Senator Joe McCarthyg mix together the liberal and the leftist interpretations. Purely leftist accounts would include David Caute’s The Great Fear: The AntiCommunist Purge under Truman and Eisenhower and Athan C. Theoharis’ Seeds o f Repression: Harry S. Truman and the Origins OF McCarthyism.lo This article’s purpose is twofold. First, it will attempt to determine whether McCarthy uncovered any evidence of proCommunist individuals in the federal government. In so doing, the article will focus on the Tydings Committee hearings of 1950, which investigated McCarthy’s first charges of pro-Communist infiltration and which placed McCarthy in the national spotlight. Buckley and Bozell, who go over this episode in detail, appropriately regard it as a “testing ground for judging both McCarthy and McCarthy’s enemies.”’ Since the standard historical version of McCarthyism denies that McCarthy ever found any subversives or security risks in government, to show even one instance when McCarthy was right, or even partially right, would be a significant revision of historical orthodoxy. Second, this article will attempt an overall assessment of McCarthy and M cCarth yism . From Lenin onward Soviet Communist leaders have always preached the necessity of underground activities. Government has been the key target for infiltration. Actual evidence of this in numerous countries is overwhelming. In government Communists have engaged in espionage and acted to influence government policies in a pro-Communist direction. Many of the individuals engaged in these activities were Communist Party members; others were fellow travelers, who despite the lack of party discipline, sought to advance the interests of Soviet Communism.12 Support for the Soviet Union as the “workers’ paradise” was highly fashionable among American intellectuals in the Depression-ridden 1930s. During the time of the Popular Front, Communists worked easily with non-Communists of leftist and liberal views. The Nazi-Soviet Pact of 1939 had a disillusioning impact on these nonCommunists, but the later wartime alliance between the Soviet Union and the United States renewed their sympathy for 133 Modern Age LICENSED TO UNZ.ORG ELECTRONIC REPRODUCTION PROHIBITED Communism. Given this milieu and the fact that large numbers of intellectuals entered the federal government during Franklin Roosevelt’s administrations, the existence of significant numbers of Communists and pro-Communists in the federal government was ine~itab1e.l~ While the United States had enacted a number of laws and regulations proscribing Communists from the federal government, these were loosely enforced during World War 11, despite evidence from the FBI and elsewhere of extensive Communist subversion and espionage. In large part, this inaction was explainable by the prevailing pro-Soviet climate of opinion resulting from the wartime alliance. The Soviet Union was painted in glowing terms by American government propaganda organs and by most of the private media. There seemed to be no need to be wary of allies who were engaged in the common cause of combating Nazi Germany. The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) actually cooperated with the NKVD (the forerunner of the KGB),and President Roosevelt even went so far as to consider allowing an official NKVD headquarters in the United States.I4Obviously, in such an atmosphere, charges of Communist infiltration, even if proved true, would be little cause of concern. As American hostility toward the Soviet Union began to develop in 1945, however, evidence of Communist influence in the government became looked upon in a wholly different light. Simultaneously, evidence of Communist penetration mounted rapidly. In February 1945 federal officials found numerous classified government documents, some marked “top secret,” in the New York office of the pro-Communist journal Amerasia. Elizabeth Bentley and Whittaker Chambers told their stories of Communist espionage to the FBI. And in the fall of 1945 a Soviet cipher clerk, Igor Gouzenko, defected to Canadian authorities, bringing documentary proof of the existence of a far-flung Soviet spy apparatus operating in the American, British, and Canadian governments. Ottawa quickly conveyed this in- formation to Washington.15 These various revelations genuinely alarmed the Truman administration, but out of a desire to avoid publicity it only slowly began to counteract this subversion. In part this hesitation was probably due to the desire to acquire greater proof so as not to alarm innocent individuals. At least as significant, however, was the fear of open scandals that not only would be detrimental to the heads of various government agencies but also might discredit the Democratic Party and its policies. Conventional histories have stressed the self-interest of Republicans and conservatives in exploiting any possibility of Communist penetration. They have failed, however, to point out that leading government officials in the Truman administration had nothing to gain and everything to lose by publicly exposing pro-Communists in government. Undoubtedly, the natural reaction of a politician is to keep the skeletons locked in the closet. Where evidence seemed conclusive and where posts of the highest American security were involved, such as the cases of Alger Hiss and Harry Dexter White, the Truman administration tried quietly to reduce those individuals’ authority, and they were slowly eased out of the federal government. A fundamental concern was how to remove subversive individuals from government civil service positions without violating their rights as civil servants. During the first century of the United States’ existence, federal employees were appointed on the basis of political belief and party loyalty and could be removed at the whim of the administration. A new administration brought in its own set of federal employees. This so-called spoils system was eliminated by the Civil Service Act of 1883, which made it unlawful for the federal government to inquire into an employee’s political beliefs. This prohibition was altered by later legislation and executive orders to deal with security risks.” During World War I President Woodrow Wilson issued a confidential executive Spring 1985 134 LICENSED TO UNZ.ORG ELECTRONIC REPRODUCTION PROHIBITED order to the heads of federal departments and agencies that employees considered to be security risks should be removed. With the emergence of the threat of totalitarian communism and fascism, Congress in 1939 enacted Section 9A of the Hatch Act that prohibited federal employees from belonging to organizations that advocated the overthrow of America’s constitutional form of government. And in 1942 the Civil Service Commission enunciated loyalty criteria for hiring. In cases of “reasonable doubt” as to loyalty, it held that an individual must be denied government employment.18 With the revelations of Communist infiltration, Congress in 1946 granted the right of summary dismissal to the heads of several federal agencies, including the Department of State. The particular legislation dealing with the State Department was the so-called McCarran Rider to the State Department Appropriations Bill, initially passed on July 6, 1946, and renewed yearly until 1953. Finally President Truman, on March 22, 1947, trying to head off more extensive demands made by several committees of Congress, issued Executive Order 9835, which established a comprehensive loyalty program for the federal g0~ernment.l~ Much of the impetus for the discharge of federal employees came from congressional investigations of Communist subversion. This congressional scrutiny of federal employees so irritated the Truman administration that, on March 13, 1948, President Truman issued an order prohibiting the release of loyalty and security information to anyone outside the executive branch. Congress was, in short, to be left in the dark as to security matters; the executive branch would be policing itself. Given the natural instinct for political self-preservation, there would be no incentive for the Truman administration to dig up problems for which it, at least in part, was responsible. By depriving Congress of the relevant information necessary to investigate the workings of the executive branch, Truman was denying the investigatory power of Congress. Congress had asserted such an authority since the early days of the Republic, and it would seem to be a fundamental power of a legislature, without which, as James Burnham writes, “Congress would retain only the name of legislature.”20 Certainly, the liberal establishment later championed congressional investigations of the executive branch during the Nixon, Ford, and Reagan administrations. In claiming complete authority for administering federal security practices, it would seem that Truman was taking on the role of the “imperial presidency” that liberals since the 1970s have so vociferously decried. Given this information blackout, it was only natural for many Americans to think that the White House was covering up security problems. The greatest concern was the State Department, where only two security risks had been detected between 1947 and 1950. What made antiCommunists especially leery about the State Department was the Communist victory in China in 1949. Since the last years of World War 11, American aid to Chiang Kai-cheks Nationalist Chinese government had been less than firm. A number of State Department officials had been highly critical of the Nationalist government and had sympathized with the Chinese Communists, alleging that they were not really Communists but “agrarian reformers.” They advocated that the United States transfer its official recognition from the Nationalists to the Communists. Since these views were similar to the official Communist Party line during this period, antiCommunists attributed the Communists’ victory in China to pro-Communist subversion in the State Department.” The standard liberal interpretation of these events rejects out of hand the idea that American officials could have played any role in the Communist victory in China. “China was not ours to lose” is the common refrain. Writing in this vein, Thomas Reeves maintains that the State Department admirers of the Chinese Communists “were not Communists or part of 135 Modern Age LICENSED TO UNZ.ORG ELECTRONIC REPRODUCTION PROHIBITED I I I I I a conspiracy to turn China over to the Communists. . . . They were, however, extremely displeased with the military footdragging, reactionary politics, and sordid corruption of Chiang’s regime and, like many journalists on the scene, were impressed by the Communists’ personal austerity and charm and by their espousal of liberal economic policies and orderly democratic growth.”22 Reeves’s argument evades the actual issue. Reeves seems to presume that Chinese Communism was good and that the United States should have backed it rather than the Nationalist government. In short, American policy should have been other than what it was. But the actual question was whether the Chinese Communist sympathizers in the State Department carried out the official American policy of supporting the Nationalist government, or whether they acted to undermine that policy. (Whether China would have gone Communist without any such subversion is irrelevant.) Moreover, there was some doubt that these same individuals could be trusted to carry out a foreign policy directed against Communist governments. In this climate of suspicion, Senator Joseph R. McCarthy made his famous speech in Wheeling, West Virginia, on February 9, 1950, in which he claimed that the State Department had harbored a large number of pro-Communist subversives. (The exact number is in dispute: McCarthy later claimed to have used the number 57; his critics contended that he said 205.) As a consequence of the publicity generated by these charges, which McCarthy repeated in subsequent speeches, the Senate on February 22, 1950, authorized the Senate Foreign Relations Committee to conduct “a full and complete study and investigation as to whether persons who are disloyal to the United States are or have been employed by the Department of State.” The Senate Foreign Relations Committee established a special subcommittee headed by Senator Millard Tydings of Maryland to conduct the investigation. Before continuing the chronology, it is necessary to mention a misapprehension which often mars the understanding of the Tydings investigation and McCarthy’s role in it. In his speeches McCarthy sometimes stated that there were actual Communist Party members in the State Department. Thus, his critics have argued that he failed to prove the existence of any such Communists. But before the Senate McCarthy spoke merely of loyalty risks, and these were what the Tydings Committee was authorized to i n v e ~ t i g a t e . ~ ~ The Tydings Committee opened its hearings on March 8, 1950. McCarthy submitted information on 110 individuals for investigation. The Truman administration reluctantly agreed to let the Tydings Committee study the loyalty files of 71 identifiable cases cited by McCarthy. Nine of the cases were discussed publicly, with the accused individuals invited to appear personally before the Committee to reply to the charges. Six of these individuals availed themselves of this opportunity. On July 17, 1950, the Tydings Committee released its final report signed by the three Democrats on the Committee Tydings, Brien McMahon of Connecticut, and Theodore Green of Rhode Island. The two Republicans on the Committee Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., of Massachusetts and Bourke Hickenlooper of Iowa - refused to sign the majority report. Lodge filed a dissenting minority report, and Hickenlooper opted not to sign or write anything. The majority report scathingly attacked McCarthy’s charges as “a fraud and a hoax perpetrated on the Senate of the United States and the American people.” It unambiguously cleared all the individuals cited by McCarthy. While anti-Communists and Republicans at the time branded the majority report a “whitewash,” liberal historians have been in complete accord with the Committee’s findings. For example, Reeves writes of the majority report’s “painstaking and impressive compilation and analysis of evidence.’Iz4 In contrast, Buckley and Bozell, who analyzed the backgrounds of the inSpring I985 136 LICENSED TO UNZ.ORG ELECTRONIC REPRODUCTION PROHIBITED dividuals cited by McCarthy, concluded that McCarthy did provide the Tydings Committee with a considerable number of security and loyalty risks. Of course, the finding of only one risk would overturn the conventional interpretation that McCarthy’s charges were totally without substance. To determine whether McCarthy’s charges had any validity calls for a review of his two most significant cases. The individual whom McCarthy considered his major find was Owen Lattimore, whom he labeled “the top Russian spy.” While not formally a member of the State Department, Lattimore had numerous close connections with it. He had served as the American political advisor to Chiang Kai-chek. In 1944 he had accompanied Vice President Henry Wallace on his trip to Siberia and China. In 1945 he had been appointed by President Truman as a member of the Pauley reparations mission to Japan. Furthermore, Lattimore was a leading figure in the Institute of Pacific Relations, which had many ties to the State Department.25 Lattimore’s numerous writings showed him to be an ardent apologist for Soviet and Chinese communism. Even Reeves admits that “Lattimore himself was no doubt a fellow traveler” and that the Institute of Pacific Relations was “infiltrated by Communists and fellow travelers”; but he maintains that the IPR and its publications had “no demonstrable effect on the White House or the State Department.”26 Similarly, Lately Thomas writes that Lattimore “apparently had helped smooth the way for the Communists’ eventual triumph. All this, however, even when viewed in the least creditable light, added up to far less than ‘espionage agent’ or even ‘bad security risk.’ “z7 While McCarthy did not prove the charge that Lattimore was “the top Russian spy,” the arguments by Reeves and Thomas would seem to imply that Lattimore was a security or loyalty risk, rather than exculpate him from this charge as they think. In 1952 the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee, headed by Senator Pat McCarran of Nevada, probed much deeper into Lattimore’s background in its Institute of Pacific Relations Hearings. It discovered that his writings were not only pro-Communist but dovetailed completely with the Soviet Communist line of the particular moment. And considerable evidence showed that he was aware that reality differed from what he wrote. For example, he had repeatedly contended that (Outer) Mongolia was free from Soviet control, yet when seeking to visit that country he had sought permission from Soviet authorities. Former Soviet General Alexander Barmine testified that Lattimore was an actual member of Soviet Military Intelligence. (Ex-Communist Louis Budenz had testified at the Tydings Committee hearings that Lattimore was a Communist.) The final report of the McCarran Committee, which had the unanimous support of the members, concluded that Lattimore was a “conscious articulate instrument of the Soviet conspiracy.”28 The conclusions of the McCarran Committee report, of course, are not accepted by liberals. For example, Fred J. Cook, in The Nightmare Decade, while acknowledging that Lattimore’s activities and writings followed the Soviet Communist line, responds that “all of this easily could have been read as an ideological blind spot, such as many had in the different crises of that time, when the great menace of the world was posed by the Fascist powers.” Besides, “Just how was one to define a ‘sympathizer’? One man’s ‘sym’ pathy’ is another’s common sense.”2g Questions of motivation, however, have nothing to do with the issue of whether Lattimore was a loyalty risk. Vidkun Quisling no doubt believed he was aiding Norway by supporting Nazi Germany; this made him no less a traitor to his country. Another of McCarthy’s significant loyalty risk cases involved John Stewart Service, a career diplomat stationed in China during World War 11. Service’s prolific diplomatic dispatches had consistently portrayed the Nationalist government as totalitarian, inefficient, and corrupt, while 137 Modern Age LICENSED TO UNZ.ORG ELECTRONIC REPRODUCTION PROHIBITED the Communists were depicted as democratic, progressive, and honest. Upon returning to the United States in 1945, Service was caught transmitting classified documents to the editor of a proCommunist journal, A r n e r a s i ~ . ~ ~ The Arnerusia case was a complex affair which t h e Tydings Committee investigated. The story of the case is as follows: After noticing the appearance of confidential material in Arnerusia, Office of Strategic Services (OSS) agents broke into the journal’s office in March 1945 and discovered a large number of highly classified government documents, some labeled “top secret.” Keeping the break-in secret, the FBI undertook physical surveillance of those people thought to be involved in the theft of the documents. On June 6, 1945, the FBI arrested six persons, among whom was Service, and seized a large number of government documents that were in their posse~sion.~~ The six suspects were arraigned on charges of conspiracy to steal government documents related to the national defense. The lawyers of the accused argued that the government documents, although classified, were innocuous and that their clients were guilty of nothing more than the accepted practice of obtaining background information from government sources. The grand jury indicted only three of the individuals, Service being exonerated. In the end the Justice Department prosecuted on the lesser crime of merely conspiring to steal government documents, and two of the suspects, including Amerusiu editor Philip Jaffe, pleaded nolo contendere and received minor fines. (The charge against the third person was dropped.) By November 1945 the Arnerasia case was officially cl0sed.3~ Republicans and anti-Communists were enraged that the Justice Department had not prosecuted more vigorously - that it had failed to emphasize Arnerusiu’s proSoviet orientation and Jaffe’s extensive Communist connections. In contrast, the Justice Department held that an insufficient number of the seized documents were related to national defense, that there was no evidence that they were passed beyond the confines of the journal, and that much of the evidence was tainted - illegal searches and seizures, unauthorized wiretaps. Service was subsequently cleared by the State Department LoyaltySecurity Board on six different occasions, and the Tydings Committee merely chided him for being “extremely i n d i ~ c r e e t . ” ~ ~ The facts of the case allow for a less sanguine interpretation. Even if the information passed along was innocuous, it would seem that the very transmission of classified documents to a journal with Communist ties would be sufficient to make Service a security risk. Moreover, while the documents seized may have seemed harmless, there is no assurance that these included all the documents Furthermore, transmitted to Arner~siu.~4 the innocuous nature of the seized documents was not universally apparent. Undersecretary of State Joseph Grew did not regard them as such in 1945 when he ordered the arrests. As Anthony Kubek writes in The Amerasia Papers, “Many of the pilfered documents were of vital diplomatic and military importance in wartime, just as the original classifications indicated.” In addition, one of the FBI’s secret recordings of Service’s meetings with Jaffe revealed a discussion of military plans which Service termed “very secret .”35 Summing up the case, Earl Latham, who is hardly a McCarthy sympathizer, writes: Although it seemed to be virtually impossible to establish espionage by courtroom standards, there is the silent testimony of the documents themselves. There was either espionage in the Amerusiu case or the security procedures of the Department of State were so grotesquely lax that the responsible officials should have been disciplined.36 All of this does not conclusively prove that Service was consciously disloyal. But it would seem to place him in, at least, a questionable category. In December 1951, after the conclusion of the Tydings HearSpring 1985 138 LICENSED TO UNZ.ORG ELECTRONIC REPRODUCTION PROHIBITED ings, the Civil Service Loyalty Review Board concluded that there was “reasonable doubt” as to Service’s loyalty and ordered his removal from the State Department.37 Service fought in the federal courts for reinstatement, and the Supreme Court in 1957 ruled in his favor on a technicality: that Service’s discharge violated State Department regulations which required an adverse ruling from the State Department’s own Loyalty-Security Board. Service’s dismissal was expunged from the record, but given his background it seems hardly unreasonable for McCarthy to have doubted his r e l i a b i l i t ~ . ~ ~ A fundamental difference between the liberal historians and McCarthy and his supporters revolves around the definition of a loyalty-security risk. It should be pointed out that the State Department was operating under dual authority during this period. It was not only under the overall Civil Service loyalty program established by Truman’s executive order, but it was also under a security program originally established by the McCarran Rider of 1946. Suspect employees were investigated by the State Department’s LoyaltySecurity Board. And the security standard was less lenient toward the employee, lacking the jurisprudential safeguards of the Civil Service loyalty program. It simply called for summary dismissal in the “interests of national security.” And there needed to be only a “reasonable doubt” of the employee’s reliabilit~.~s Still, all this does not clarify the definition of a security risk. Perhaps it could be argued that the definition was purely subjective. McCarthy thought Lattimore a security risk, but the State Department did not. Liberal historians, however, do not accept a subjective standard, since they categorically maintain that McCarthy failed to find any security risks. They cannot hold that a security risk is what the executive branch regards it to be because the executive branch later validated a number of McCarthy’s charges. In short, liberal historians assume an absolute standard in determining a security risk. While liberal historians assume such an absolute standard, however, they do not define it. If belonging to front groups, following the Communist line, being identified as a Communist, illicitly transmitting classified documents to Communists were not enough to label one a security risk, what was? Sometimes it seems that McCarthy’s critics assumed that McCarthy had to prove individuals guilty of overt crimes treason, espionage, or at least membership in the Communist Party. But such was not necessary. Other laws dealt with actual crimes. The purpose of the loyaltysecurity regulations was to provide the government with reliable personnel, keeping potential spies and subversives out of sensitive positions.40 Since there would seem to be no absolute definition of a loyalty or security risk, one means of judging McCarthy’s (and his critics’)view of the issue is to look at other episodes of American history when America’s leaders believed the nation’s survival to be threatened. During and immediately after the American Revolution, suspected pro-British Tories were denied political and property rights by most of the states. The Alien and Sedition Acts enacted in John Adams’s administration were intended to restrict criticism of the Federalist government during the Quasi-War with France. Thomas Jefferson’s government infringed on many American freedoms (being most extreme in engaging in illegal searches and seizures) during the period of the Embargo Act. During the Civil War Abraham Lincoln suspended the writ of habeas corpus throughout the country and jailed individuals for simply criticizing the war effort. During World War I the Woodrow Wilson administration had numerous alleged subversives and radicals imprisoned. And Franklin Roosevelt’s most notorious infringement of civil liberties was the internment of Japane~e-Americans.~~ Compared with these infringements on traditional American liberties, the impact of McCarthy’s anti-Communist activities would seem to be rather mild. For McCar- Modern Age 139 LICENSED TO UNZ.ORG ELECTRONIC REPRODUCTION PROHIBITED thy provided at least prima facie evidence of an individual’s being a security threat. In contrast, during the Civil War hearsay evidence of one witness was often enough to have someone jailed. And Franklin Roosevelt did not require any evidence of individual subversive activity to intern the Japanese-Americans as a group. Not only was McCarthy’s evidence much more substantial, but the punishment meted out was considerably milder. The penalty resulting from McCarthy’s findings was the loss of a government job, which, at the time, was not considered a right. In fact, the Truman administration’s loyalty board commonly stated that a government job was a privilege.42In sum, while McCarthy’s actions did not deprive any citizen of any traditional American liberties, the security practices of Jefferson, Lincoln, Wilson, and Franklin Roosevelt did deny rights traditionally protected by the Constitution. Historians, however, have not criticized those presidents as they have McCarthy. Throughout various eras in American history, civil liberties have been restricted when the nation’s security has been perceived as endangered. Thus, in the late 1940s and early 1950s the United States government established loyalty and security restrictions because it was widely believed that Soviet communism threatened the country. McCarthy merely sought to enforce the laws that were on the books. To point out that McCarthy did expose some pro-Communist security risks, while going contrary to the conventional liberal historiography, does not deal with what can be called the anti-Communist critique of McCarthy. Individuals who have held this view, such as Ralph de Toledano and Whittaker Chambers, supported congressional investigations of communism but viewed McCarthy’s methods to be counterprod~ctive.~~ As Guenter Lewy writes in a recent American Enterprise Institute publication, “Perhaps the greatest damage that Senator Joseph McCarthy has caused this nation is that he succeeded in casting doubt upon the need for a serious and responsible concern with Communism and domestic security. His excesses have discredited the cause of anti-Communi~rn.”~~ In short, from this point of view, McCarthy was detrimental, not because of any alleged harm done to American civil liberties, but because he weakened the cause of anti-communism. That McCarthy was a flawed individual has been acknowledged even by his supporters. His knowledge of communism was limited. His judgments were hasty. He often resorted to crude exaggeration. He was not the foremost congressional investigator of Communist subversion. As the pro-McCarthy William Rusher, who is publisher of National Review and who served for over a year as special counsel to the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee, writes: McCarthy’s substantive contributions to the documentation of the important story of domestic Communist subversion, while valuable, were not in most cases achievements of the first rank not comparable, for example, to HCUA’s brilliant probe of the HissChambers case, or the ISSC‘s investigation of the Institute of Pacific Relation~.~~ As Buckley and Bozell emphasize, however, McCarthy’s primary function was not that of a scholarly investigator of Communist subversion but of a publicist. To get the public’s attention American politicians have traditionally resorted to exaggeration. For example, Franklin Roosevelt and Harold lckes continually attacked “economic royalists” and branded the World War I1 isolationists as pro-Nazi trait01-s.~~ In 1964 Democrats and liberals repeatedly labeled the Republican presidential nominee, Barry Goldwater, a fascist, a racist, and an insane proponent of nuclear holocaust.47About McCarthy’s method, Buckley and Bozell conclude: “McCarthy’s record is nevertheless not only much better than his critics allege but, given his metier, extremely good.”48If this assessment be excessive, it does not seem that McCarthy’s method differed from Spring 1985 140 LICENSED TO UNZ.ORG ELECTRONIC REPRODUCTION PROHIBITED 1 what has been commonplace in the roughand-tumble of American politics. Buckley and Bozell attribute McCarthy’s success in popularizing anti-communism to his free-swinging method. Since Buckley and Bozell published their work in 1954, it could conceivably be said that they had not yet witnessed the ultimate negative effects of McCarthy’s method. While this method achieved the shortterm success of making Communist subversion a popular issue, in the long run it may have contributed to the demise of anti-communism.49 McCarthy did provide a much-needed target for American liberals, who in the early 1950s found themselves on the defensive. Liberals feared that the investigations of communism could undermine American liberalism - its domestic as well as its foreign policy agenda - and they believed that this was, in fact, the real intent of the anti-Communists. Such a view has been enshrined in the conventional histories of the McCarthy era. For example, Fred J. Cook writes that anticommunism was actually an attack on the New Deal “through a propaganda campaign that would equate all liberalism with socialism and communism in a formula designed to frighten the wits out of the least volatile electorate in the Similarly, Earl Latham describes McCarthyism as an “agent of fundamentalist conservatism.” “The Communist issue was the cutting edge for the attack” on entrenched l i b e r a l i ~ m . ~Believing ~ that the antiCommunists’ main goal was the destruction of American liberalism, most liberals became more fearful of anti-communism than of communism. To ward off the anti-Communist challenge, liberals could not just remain on the defensive, denying the validity of the numerous charges of Communist infiltration. Such a piecemeal defensive strategy was bound to be overwhelmed. To achieve success it was necessary to take the offensive and discredit the entire anti-Communist effort. McCarthy’s freeswinging methods (though objectively not differing from the usually rough American political milieu) gave them this opportunity. Focusing on and distorting McCarthy’s methods, liberals were able to shift the major political issue in American politics away from that of the threat of Communist subversion to McCarthy’s alleged threat to civil liberties. Liberalism came to depict McCarthy as the personification of evil and linked all anti-Communists with McCarthy. The liberal counterattack, of \course, proved a total success. Since the mid-1950s any charge of Communist infiltration has been quickly silenced by the charge of McCarthyism, without any concern about the merit of the allegation. While McCarthy as an issue was the particular means by which liberal anti-antiCommunists quashed anti-communism, it would be incorrect to blame McCarthy for this turn of events. Since in the early 1950s (like today) liberalism dominated the centers of power - media, education, government - the anti-Communist rnovement faced a veritable Catch-22 situation. To be successful anti-communism needed to be popularized among the American people. But it required the emergence of visible anti-Communist champions. Given the dominance of liberalism, especially in the information sector, any highly visible anti-Communist would have been vilified just like McCarthy. (Observe the liberal establishment’s character assassination of its perceived enemies: Whittaker Chambers, Barry Goldwater [now rehabilitated], Douglas MacArthur.) Perhaps if the individual were extremely careful, it would have taken longer, but the ultimate result would have been just the same. While the conventional liberal portrayal of McCarthy is an almost total distortion of his record, the anti-Communist critique of McCarthy errs in underestimating the power of liberalism. Anti-communism failed not because of McCarthy’s personal flaws, but because of the overwhelming dominance of liberal ideology, which rules out any strong strike at communism. And it is only when the liberal stranglehold over public discourse in America is broken that Joseph R. McCarthy will finally receive a fair hearing. Modern Age 141 LICENSED TO UNZ.ORG ELECTRONIC REPRODUCTION PROHIBITED IFred J. Cook, The NightmareDecade: The Life and Times of Senator Joe McCarthy (New York, 1971), p. 20. 2Richard H. Rovere, Senator Joe McCarthy (New York, 1959). 3Thomas C. Reeves, The Life and Times of Joe McCarthy: A Eiography (New York, 1982), p. xi. ‘William F. Buckley, Jr., and L. Brent Bozell, McCarthy and His Enemies: The Record and Its Meaning (Chicago, 1954). 5Willmoore Kendall, The Conservative Affirmation (Chicago, 1963), pp. 57-58. %tely Thomas (Robert V. Steele), When Even Angels Wept: The Senator Joseph McCarthy Affair A Story Without a Hero (New York, 1973). ’Earl Latham, The Communist Controversy in Washington: From the New Deal to McCarthy (Cambridge, MA, 1966). 8Robert Criffith, The Politics of Fear: Joseph R. McCarthy and the Senate (Lexington, KY, 1970). gDavid Caute, The Great Fear: The Anti-Communist Purge under Truman and Eisenhower (New York, 1978). IOAthan G. Theoharis, Seeds o f Repression: Harry S. Truman and the Origins of McCarthyism (Chicago, 1971). llBuckley and Bozell, p. 67. I2Forexamples of Communist spies in other countries see: Gordon W. Prange, with Donald M. Goldstein and Katherine V. Dillon, Target Tokyo: The Story of the Sorge Spy Ring (New York, 1984); Harry Rositzke, The KGB: The Eyes of Russia (Garden City, NY, 1981). I3Eugene Lyons, The Red Decade, The Stalinist Penetration of America (Indianapolis, 1941); Harvey Klehr, The Heyday of American Communism: The Depression Decade (New York, 1984). “Bradley F. Smith, The Shadow Warriors:O.S.S. and the Origins of the CLA. (New York, 1983), pp. 338-59. I5Anthony Kubek, “Introduction,” The Amerasia Papers: A Clue to the Catastrophe of China, vol. 1. Prepared by the Subcommittee to Investigate the Administration of the Internal Security Act and Other Internal Security Laws of the Committee on the Judiciary, U.S.Senate, 91st Cong., 1st sess. (Washington, 1970), pp. 1-113; James Barros, “Alger Hiss and Harry Dexter White: The Canadian Connection,” Orbis, 21:3 (Fall 1977), pp. 593-605. IGBarros, pp. 593-605. ”Eleanor Bontecou, The Federal Loyal&-Security Program (Ithaca, NY, 1953), pp. 1-34. I8lbid. IgIbid.,pp. 22, - 290; Guenter Lewy, The Federal Loyalty-Security Program: The Need for Reform (Washington, 1983), p. 4. 2oJamesBurnham, “The Investigatory Power of Congress,” in William F. Buckley, Jr., ed., The Committee and Its Critics: A Calm Review of the House Committee on Un-American Activities (Chicago, 1962), p. 60. 21Anthony Kubek, How the Far East Was Lost: American Policy and the Creation of Communist China, 1941-1949 (Chicago, 1963). 22Reeves, p. 217. 23Buckley and Bozell, pp. 54-55. Z‘Reeves, p. 304. 25For a critical account of Lattimore’s background see John T. Flynn. The Luttimore Story (New York, 1953). 26Reeves,p. 255. 27LatelyThomas, p. 144. 28U.S. Senate, Committee on the Judiciary, Internal Security Subcommittee, Institute of Pacific Relations, Hearings, 82d Cong., 1st sess., Final Report (Washington, 1951), p. 224. 2gCook,pp. 372, 376. 30K~bek,Amerasia Papers, pp. 31-34. 311bid. Ybid., 43-57. W i d . , 57-61; Reeves, p. 305. 3‘James Burnham, The Web ofSubversion (New York, 1954), p. 214. 35Kubek, Amerasia Papers, pp. 78, 39. 36Latham, p. 207. 37K~bek, Amerasia Papers, pp. 65-66. %id., pp. 66-67. 39Buckley and Bozell, pp. 18-30; Bontecou, pp. 48-51. *Lewy, p. 14. “For discussions of these infringements on civil liberties see Leonard W. Levy, Jefferson& Civil Liberties: The Darker Side (Cambridge, MA, 1963); Dean Sprague, Freedom Under Lincoln (Boston, 1965). 42Bontecou, pp. 205-7. .%eorge H. Nash, The Conservative Intellectual Movement in America Since 1945 (New York, 1976), pp. 114-15. 44Lewy,p. 2. 45WilliamA. Rusher, Special Counsel: An Insider’s Report on Senate Investigations into Communism (New Rochelle, NY, 1969), p. 242. @Stephen J. Sniegoski, “Unified Democracy: An Aspect of American World War I1 Interventionist Thought,” The Maryland Historian, 9: 1 (Spring 1978). “Lionel Lokos, Hysteria 1964: The Fear Campaign Against Barry Coldwater (New Rochelle, NY, 1967). “Buckley and Bozell, p. 277. 49By the early 1970s William F. Buckley had come to believe that McCarthy had been injurious to American conservatism. Nash, p. 123. “Cook, p. 32. 51Latham,p. 423. Spring 1985 142 LICENSED TO UNZ.ORG ELECTRONIC REPRODUCTION PROHIBITED