A Randomized Controlled Comparison of Electro

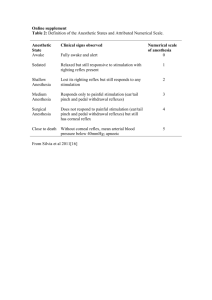

advertisement

AMBULATORY ANESTHESIA SOCIETY FOR AMBULATORY ANESTHESIA SECTION EDITOR PAUL F. WHITE A Randomized Controlled Comparison of Electro-Acupoint Stimulation or Ondansetron Versus Placebo for the Prevention of Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting Tong J. Gan, MB, FRCA, FFARCS(I), and Gregory Georgiade, MD† Licentiate in Acupuncture*, Kui Ran Jiao, MD*, Michael Zenn, MD†, Departments of *Anesthesiology and †Plastic Surgery, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina In this study we evaluated the efficacy of electroacupoint stimulation, ondansetron versus placebo for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV). Patients undergoing major breast surgery under general anesthesia were randomized into active electro-acupoint stimulation (A), ondansetron 4 mg IV (O), or sham control (placement of electrodes without electro-acupoint stimulation; placebo [P]). The anesthetic regimen was standardized. The incidence of nausea, vomiting, rescue antiemetic use, pain, and patient satisfaction with management of PONV were assessed at 0, 30, 60, 90, 120 min, and at 24 h. The complete response (no nausea, vomiting, or use of rescue antiemetic) was significantly more frequent in the active treatment groups compared with placebo both at 2 h (A/O/P ⫽ 77%/64%/42%, respectively; P ⫽ 0.01) and 24 h postoperatively (A/ O/P ⫽ 73%/52%/38%, respectively; P ⫽ 0.006). The P ostoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) are among the most unpleasant experiences associated with surgery and are the most common reasons for poor patient satisfaction in the postoperative period. In one survey, PONV was among the top five most undesirable outcomes after surgery (1). Current prevention and treatment of PONV involve the use of drugs. However, all antiemetics are associated with side effects. Although most side effects are relatively minor, others are potentially more serious. For example, ondansetron is associated with headache, abdominal pain, and increased liver enzymes. Dopamine antagonists may cause extrapyramidal side effects, neuroleptic syndrome, and hypotension. Accepted for publication April 6, 2004. Address correspondence and reprint requests to T. J. Gan, Department of Anesthesiology, Duke University Medical Center, Box 3094, Durham, NC 27710. Address e-mail to gan00001@mc.duke.edu. DOI: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000130355.91214.9E 1070 Anesth Analg 2004;99:1070–5 need for rescue antiemetic was less in the treatment groups (A/O/P ⫽ 19%/28%/54%; P ⫽ 0.04). Specifically, the incidence and severity of nausea were significantly less in the A group compared with the other groups, and in the O group compared with the P group (A/O/P ⫽ 19%/40%/79%, respectively). The A group experienced less pain in the postanesthesia care unit, compared with the O and P groups. Patients in the treatment groups were more satisfied with their management of PONV compared with placebo. When used for the prevention of PONV, electro-acupoint stimulation or ondansetron was more effective than placebo with greater degree of patient satisfaction, but electro-acupoint stimulation seems to be more effective in controlling nausea, compared with ondansetron. Stimulation at P6 also has analgesic effects. (Anesth Analg 2004;99:1070 –5) Acupuncture has been demonstrated to be effective for the prevention and treatment of PONV. Lee and Done (2) in a meta-analysis found the numberneeded-to-treat (NNT) of 4 (3– 6; 95% confidence interval) for preventing early nausea and NNT of 5 (4 – 8; 95% confidence interval) for preventing early vomiting. (NNT ⫽ number of patients needed to treat, compared with control, before one patient will have an effective response.) More recently, Coloma et al. (3) compared transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation using the Relief Band® with ondansetron for the treatment of established PONV. However, no study has been reported comparing electroacupuncture with ondansetron alone for the prevention of PONV. We therefore design a randomized, sham-controlled study to test the hypothesis that electro-acupoint stimulation is an effective alternative to ondansetron for PONV prophylaxis. A secondary objective was to determine whether electro-acupoint stimulation at P6 has analgesic effects. ©2004 by the International Anesthesia Research Society 0003-2999/04 ANESTH ANALG 2004;99:1070 –5 AMBULATORY ANESTHESIA GAN ET AL. ELECTRO-ACUPOINT STIMULATION VS ONDANSETRON FOR PREVENTION OF PONV AND PAIN 1071 Methods After IRB approval and written informed patient consent had been obtained, 77 consecutive patients undergoing major breast surgery who met inclusion criteria were randomized into three groups: active electro-acupoint stimulation (A), ondansetron 4 mg IV (O), and sham control (placement of electrodes without electro-acupoint stimulation; placebo [P]). Patients who were pregnant, were experiencing menstrual symptoms, were using a permanent cardiac pacemaker, had previous experience with acupuncture therapies, had received any antiemetic medication or had experienced nausea, vomiting, or retching within 24 h of surgery were excluded. Randomization was achieved using a random number generator in a sealed envelope technique. A qualified and trained acupuncturist determined the position of P6 acupoints bilaterally and attached a surface electrode (HANS® electrodes; Huawei Ltd., Beijing, PRC); a negative surface electrode was placed on the dorsum aspect of the forearm, directly opposite P6. The electrical stimulation unit (HANS® dual channel unit; Huawei) (Fig. 1) was turned on to determine the accurate location of the acupoint by eliciting a “de-chi” sensation, a tingling and numbness sensation associated with correct identification of an acupoint. Once this was ascertained, the current was adjusted so that the patients continued to feel the “de-chi” sensation. The stimulation unit was set on 2–100 Hz alternating waveform. To best maintain patient blinding, the O and the P groups had similar surface electrodes placed as in the A group. However, the electrical stimulation unit was not turned on and remained at the “off” position for the duration of the study. All patients were also told that the device produced an electrical current that they may or may not feel. The screen on the unit (measuring 4 ⫻ 2 cm) was covered with an opaque tape in all groups so that the clinicians and research personnel were unaware if the unit was on or off. Electrical stimulation at the acupoints was applied at least 30 min, but not longer than 60 min, before induction of anesthesia and was continued to the end of surgery, when they were removed before awakening. All patients received fentanyl 100 g IV and midazolam 2 mg IV premedication in the preoperative holding area before going into the operating room. Study drugs were prepared by the pharmacists not directly involved in the study and consisted of either ondansetron 4 mg (2 mL) or an equivalent volume of saline (for the A and P groups), and were administered to the subjects at induction of anesthesia. The anesthesiologists and care providers were blinded to the study group as the screen on the HAN’s unit was concealed. The intraoperative anesthetic regimen was standardized. Induction of anesthesia was achieved with propofol 1.5–2 mg/kg and tracheal tube placement was aided Figure 1. HANS® dual channel unit. by succinylcholine 1 mg/kg or rocuronium 0.6 mg/kg. Isoflurane at 0.5%–1.5%, nitrous oxide 50% in oxygen, and supplemental fentanyl up to 4 g · kg⫺1 · h⫺1 were used to maintain anesthesia and hemodynamics (heart rate and arterial blood pressure) within 20% of baseline. Patients’ neuromuscular blockade was antagonized by neostigmine 0.07 mg/kg and glycopyrrolate 0.01 g/kg. After tracheal extubation, patients were transferred to the postanesthetic care unit (PACU). Postoperative data were collected by a separate research nurse not involved in the preoperative or intraoperative management of patients. Incidence and severity of nausea, emetic episodes, use of rescue antiemetic, analgesia, and sedation (Ramsay sedation score) were assessed at baseline, postoperatively at time 0, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min. Subjective experience with nausea and pain at rest was scored using an 11-point linear verbal rating scale (VRS) from 0 to 10, with “0” representing no nausea or pain and “10” representing nausea or pain “as bad as it can possibly be.” Emetic episodes include vomiting or retching. Dexamethasone 8 mg was used as a rescue antiemetic, and was administered when patient complaint of nausea score was ⬎5 of 10 for 15 min or longer, 2 emetic episodes within 15 min, or at the patient’s request. Pain was treated with doses of fentanyl 25 g IV as required to keep the VRS score ⱕ3 of 10. The time to readiness for PACU discharge, when patients were fully awake, oriented, with stable vital signs, minimal pain (⬍3 on a 0 –10 scale), able to ambulate, and not experiencing any side effects, were assessed. Patients were asked about satisfaction with their PONV treatment at PACU discharge using a 0 (very dissatisfied) to 10 (very satisfied) scale. Follow-up telephone calls at 24 h were used to assess postdischarge emetic symptoms and to evaluate the patient’s satisfaction with their overall PONV management. 1072 AMBULATORY ANESTHESIA GAN ET AL. ELECTRO-ACUPOINT STIMULATION VS ONDANSETRON FOR PREVENTION OF PONV AND PAIN Previous studies performed by our group demonstrated an incidence of nausea of 65% in this population under general anesthesia without a prophylactic antiemetic (4). A sample size of 25 patients per group was determined to be adequate to demonstrate a 30% reduction in the incidence of nausea (from 65% to 35%) with ␣ ⫽ 0.05 and  ⫽ 0.8. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the demographic characteristics of patients. Fisher’s exact test and 2 tests were used for categorical data. Kruskal-Wallis test was used for non-normally distributed continuous variables, and analysis of variance was used for continuous normal data. Data were presented as mean (⫾sd), the median, or percentages, and a P value ⬍ 0.05 was considered significant. Results Seventy-seven patients were enrolled in the study. One patient from the O group did not have her scheduled surgery and one patient from the P group withdrew from participation before the administration of study procedure. Seventy-five patients completed the study. There was no difference in patient demographics among the groups (Table 1). The complete response rate (no nausea, emesis, or use of rescue antiemetic) was significantly higher in the treatment groups compared with P both at 2 h and 24 h postoperatively. The need for rescue antiemetic was less in the treatment groups (Table 2). Specifically, the incidence of nausea at 2 h postoperatively was less in the A and O groups compared with P. The degree of nausea and worst nausea score were significantly lower in the A group (Table 3). There was a trend toward less emesis in the active treatment groups at 2 h and at 24 h although these differences did not reach statistical significance. Patients in the A group experienced lower pain score in the PACU and fewer patients in this group had severe pain, defined as VRS ⬍5 of 10 (Table 3). There was no difference in the amount of postoperative analgesics. Patient satisfaction with PONV control was higher with the active treatment groups compared with P. Similarly, more patients in the active treatment groups expressed willingness to use the same modality again (Table 3). There was no difference in the duration of PACU stay, adverse events rate, and there was no residual redness on the acupuncture site in any groups. Discussion In this study, electro-acupoint stimulation at P6 was as effective as ondansetron for the prevention of PONV. However, nausea seemed to be better controlled in the A group than the O group. Interestingly, patients in the A group also experienced less pain. ANESTH ANALG 2004;99:1070 –5 Acupuncture has been shown to be effective for the prevention of PONV compared with placebo (2). A National Institutes of Health consensus panel conference concluded that acupuncture is effective for adult postoperative and chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting and probably for pregnancy-induced nausea and vomiting (5). In addition, acupuncture is also effective in the management of acute pain. Most studies investigating acupuncture for the management of PONV have compared the modality with placebo (2). However, there were methodological problems with many of the early studies, including failure to include placebo or sham-controlled groups, the use of nonstandardized anesthetic and analgesic techniques, and the absence of a recognized antiemetic as comparator. White et al. (6) compared the efficacy of acustimulation at P6 using the Relief Band® (Woodside Biomedical Systems, Carlsbad, CA) versus ondansetron, in the presence of droperidol. They found that the Relief Band® compared favorably to ondansetron 4 mg. Interestingly, the nausea score was lower at 24 hours postsurgery in the Relief Band® group compared with the ondansetron group. However, their study design was different from this study in various respects. All patients received droperidol 0.625 mg after induction of anesthesia. Patients were randomized into ondansetron, Relief Band®, or a combination of both in the recovery room. The combination group provided an additional advantage in reducing the incidence of nausea and rescue antiemetic use compared with the ondansetron group. Our study suggests that the use of acupoint stimulation is as effective as administering a single dose of ondansetron 4 mg, with a similar side effects profile. It is also cost-effective compared with ondansetron. The acupoint stimulation unit costs $200 (including 2 battery changes) and is reusable with disposable electrodes, which cost $1.84 for 4 electrodes (for each patient). The cost for ondansetron 4 mg is $16.44 (including a 2-mL syringe and a needle) (7). Assuming an acupoint stimulation unit is reusable in 200 patients, the direct cost comparison is substantial (about $3000 for ondansetron versus $600 for acupoint stimulation), although this study was not designed to investigate the detailed cost comparison among the groups. In another study, Zarate et al. (8) demonstrated that acustimulation with the Relief Band® was more effective in reducing the incidence of nausea compared with sham and placebo groups only at nine hours postsurgery, but there was no difference between the active treatment group and placebo in the earlier recovery period. No difference in the incidence of vomiting was found, suggesting that acupuncture may be more effective in relieving nausea than reducing vomiting, a similar finding to our study. Our results are in agreement with a study that showed similar efficacy between acupressure and ondansetron when used for ANESTH ANALG 2004;99:1070 –5 AMBULATORY ANESTHESIA GAN ET AL. ELECTRO-ACUPOINT STIMULATION VS ONDANSETRON FOR PREVENTION OF PONV AND PAIN 1073 Table 1. Patient Demographics Age (yr) Weight (kg) Height (cm) Race Caucasian African American ASA physical status I II III History of PONV or motion sickness Duration of surgery (min) Intraoperative fentanyl (g) Postoperative fentanyl in PACU (g) Electro-acupoint stimulation (n ⫽ 26) Ondansetron (n ⫽ 25) Placebo (n ⫽ 24) 44 ⫾ 12 77 ⫾ 21 165 ⫾ 8 47 ⫾ 10 74 ⫾ 18 163 ⫾ 7 46 ⫾ 12 77 ⫾ 17 163 ⫾ 6 20 (77) 6 (23) 22 (88) 3 (12) 18 (75) 6 (25) 6 18 2 9 (35) 212 ⫾ 97 356 ⫾ 156 63 ⫾ 72 6 16 3 9 (36) 199 ⫾ 99 343 ⫾ 199 76 ⫾ 103 7 16 1 11 (46) 222 ⫾ 96 376 ⫾ 207 91 ⫾ 106 Values are mean ⫾ sd or n (%). PONV ⫽ postoperative nausea and vomiting, PACU ⫽ postanesthesia care unit. Table 2. Incidence of Nausea, Emesis, and Complete Response Nausea 2 h Emesis 2h 24 h Complete response 2h 24 h Rescue antiemetic Electro-acupoint stimulation (n ⫽ 26) Ondansetron (n ⫽ 25) Placebo (n ⫽ 24) P value 5 (19) 10 (40) 19 (79) ⬍0.0001 3 (12) 5 (19) 2 (8) 8 (32) 6 (25) 11 (46) 0.22 0.12 20 (77) 19 (73) 5 (19) 16 (64) 13 (52) 7 (28) 10 (42) 9 (38) 13 (54) 0.01 0.006 0.04 Values are n (%). Table 3. Nausea Scores, Pain Scores, and Patient Satisfaction Electro-acupoint stimulation (n ⫽ 26) Nausea scorea 0 min 30 min 60 min 90 min 120 min Worst nauseaa Worst paina Severe pain (⬎5/10)d Patient satisfactiona Use it againd 1.1 ⫾ 2.9b 0 (0)c 0.3 ⫾ 1.0 0 (0) 0.5 ⫾ 1.6 0 (0) 0.4 ⫾ 1.4 0 (0) 0.6 ⫾ 2.0 0 (0) 0.9 ⫾ 2.2b 0 (0)c 2.8 ⫾ 2.6 5 (19%) 10 (8–10) 23 (88%) Ondansetron (n ⫽ 25) 0.9 ⫾ 2.0 0 (0) 1.1 ⫾ 2.8 0 (0) 1.2 ⫾ 2.7 0 (0–1) 0.8 ⫾ 2.1 0 (0) 0.2 ⫾ 0.8 0 (0) 2.5 ⫾ 3.6 0 (0–5) 5.8 ⫾ 3.2 12 (48%) 8.5 (6.2–10) 20 (80%) Verbal rating score ⫽ 0 –10. Data expressed in mean ⫾ sd [c median (25%–75%)]; d incidence data expressed in n (% of patients). P value from *Kruskal-Wallis or † Fisher’s exact test for three-group comparison. a b Placebo (n ⫽ 24) 1.3 ⫾ 2.6 0 (0) 1.4 ⫾ 2.2 0 (0–3.5) 2.6 ⫾ 3.2 1 (0–4.8) 2.9 ⫾ 3.1 1.5 (0–5.8) 1.7 ⫾ 2.7 0 (0–3) 4.9 ⫾ 3.2 6 (2–7.8) 6.1 ⫾ 3.6 13 (54%) 5.5 (3–10) 14 (58%) P value 0.87* 0.03* 0.005* 0.0004* 0.003* 0.0001* 0.01* 0.02† 0.007* 0.02† 1074 AMBULATORY ANESTHESIA GAN ET AL. ELECTRO-ACUPOINT STIMULATION VS ONDANSETRON FOR PREVENTION OF PONV AND PAIN PONV prophylaxis in laparoscopic cholecystectomy (9). Acustimulation with the Relief Band® has also been compared with ondansetron for the treatment of established PONV. The authors found that acustimulation was equally effective with ondansetron. However, the use of ondansetron in combination with the Relief Band® device further improved the complete response rate compared with monotherapy (3). Our study also confirms the results of a previous study by Somri et al. (10), when they compared acupuncture versus ondansetron in pediatric patients undergoing dental surgery. In this study we found that, despite comparable intraoperative and postoperative opioid use, patients in the A group had better pain relief than the O and P groups. This is the first reported study that demonstrates analgesic properties of P6. Stimulation on specific acupuncture points, e.g., Large Intestine 4 —LI4 (on the hand), Spleen 6 —SP6 (on the lower limb), and “back-shu” (paravertebral area) points have been shown to have analgesic properties. It has been demonstrated that acupuncture produces analgesia via the body endorphin system and the analgesia could be antagonized by naloxone (11). Kotani et al. (12) reported better pain relief and a 50% reduction in morphine consumption in patients undergoing abdominal procedures in the presence of acupuncture. This study demonstrates that stimulation of P6 provides additional beneficial effects on pain relief in addition to the prevention of PONV. We used two different alternating frequencies at the acupuncture points because this has been shown to have different effects on analgesia. It has been suggested that low-frequency (2– 4 Hz) stimulation resulted in the release of endorphin, and high-frequency (50 –200 Hz) stimulation involved the release of enkephalins (13). The low-frequency stimulation produced analgesia of slower onset but of longer duration of many hours. In contrast, high-frequency stimulation resulted in more rapid onset analgesia but of short duration. The use of varying frequencies may also avoid tolerance (13). We included a placebo group despite the frequent incidence of PONV from previous studies on this population. This is because there is a 30% placebo response rate when assessing efficacy of antiemetics, even in patients at high risk for developing PONV. When active comparisons are designed without placebos, one of the comparators must be the ultimate “gold standard” intervention for the control of PONV. Because this gold standard is yet unknown, active comparisons should always have an additional placebo group (14). There are important limitations to this study. Although we tried to “blind” the patients to the treatment groups by informing them that they may or may not feel the electrical stimulation, complete blinding ANESTH ANALG 2004;99:1070 –5 was not possible in conscious patients. However, the exclusion of patients who had previously received acupuncture may have reduced this bias. Acupuncture was started before induction of anesthesia for two reasons. Based on traditional acupuncture teaching, it is important to establish the right acupuncture point with the “de-chi” sensation to enhance efficacy. Second, previous studies in which acupuncture was started after induction of anesthesia had revealed less or lack of efficacy, although this mechanism is not known (2). We administered ondansetron at induction of anesthesia. The timing of administration of ondansetron could have reduced its maximal potential efficacy. Two studies suggest that when ondansetron was administered toward the end of surgery, the need for rescue antiemetic was reduced and the time to rescue antiemetic was prolonged (15,16). In conclusion, electro-acupoint stimulation or monotherapy with ondansetron is more effective than placebo for the prevention of PONV and with greater patient satisfaction. Acupuncture seems to be more effective in controlling nausea in the recovery room and, for the first time, stimulation at P6 has been shown to have analgesic effects. We thank William White, MSc, for providing statistical assistance, and Jennifer Fortney, MD, Stephen Parrillo, MD, and Ann Cannell, CRNA, for their assistance in this study. References 1. Macario A, Weinger M, Carney S, Kim A. Which clinical anesthesia outcomes are important to avoid? The perspective of patients. Anesth Analg 1999;89:652– 8. 2. Lee A, Done ML. The use of nonpharmacologic techniques to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting: a meta-analysis. Anesth Analg 1999;88:1362–9. 3. Coloma M, White PF, Ogunnaike BO, et al. Comparison of acustimulation and ondansetron for the treatment of established postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesthesiology 2002;97: 1387–92. 4. Gan TJ, Ginsberg B, Grant AP, Glass PS. Double-blind, randomized comparison of ondansetron and intraoperative propofol to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesthesiology 1996;85:1036 – 42. 5. Anonymous. NIH Consensus Conference: acupuncture. JAMA 1998;280:1518 –24. 6. White PF, Issioui T, Hu J, et al. Comparative efficacy of acustimulation (ReliefBand) versus ondansetron (Zofran) in combination with droperidol for preventing nausea and vomiting. Anesthesiology 2002;97:1075– 81. 7. Hill RP, Lubarsky DA, Phillips-Bute B, et al. Cost-effectiveness of prophylactic antiemetic therapy with ondansetron, droperidol, or placebo. Anesthesiology 2000;92:958 – 67. 8. Zarate E, Mingus M, White PF, et al. The use of transcutaneous acupoint electrical stimulation for preventing nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic surgery. Anesth Analg 2001;92:629 –35. 9. Agarwal A, Bose N, Gaur A, et al. Acupressure and ondansetron for postoperative nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Can J Anaesth 2002;49:554 – 60. ANESTH ANALG 2004;99:1070 –5 AMBULATORY ANESTHESIA GAN ET AL. ELECTRO-ACUPOINT STIMULATION VS ONDANSETRON FOR PREVENTION OF PONV AND PAIN 10. Somri M, Vaida SJ, Sabo E, et al. Acupuncture versus ondansetron in the prevention of postoperative vomiting: a study of children undergoing dental surgery. Anaesthesia 2001;56: 927–32. 11. Mayer DJ, Price DD, Raffii A. Antagonism of acupuncture analgesia in man by the narcotic antagonist naloxone. Brain Res 1977;121:368 –72. 12. Kotani N, Hashimoto H, Sato Y, et al. Preoperative intradermal acupuncture reduces postoperative pain, nausea and vomiting, analgesic requirement, and sympathoadrenal responses. Anesthesiology 2001;95:349 –56. 13. Chen XH, Han JS. Analgesia induced by electroacupuncture of different frequencies is mediated by different types of opioid receptors: another cross-tolerance study. Behav Brain Res 1992; 47:143–9. 1075 14. Tramer MR, Reynolds M, Moore RA, McQuay H. When placebo controlled trials are essential and equivalence trials are inadequate. BMJ 1998;317:875– 80. 15. Sun R, Klein KW, White PF. The effect of timing of ondansetron administration in outpatients undergoing otolaryngologic surgery. Anesth Analg 1997;84:331– 6. 16. Tang J, Wang B, White PF, et al. The effect of timing of ondansetron administration on its efficacy, cost-effectiveness, and cost-benefit as a prophylactic antiemetic in the ambulatory setting. Anesth Analg 1998;86:274 – 82.