Superstition in Strategic Decision Making: A Two

advertisement

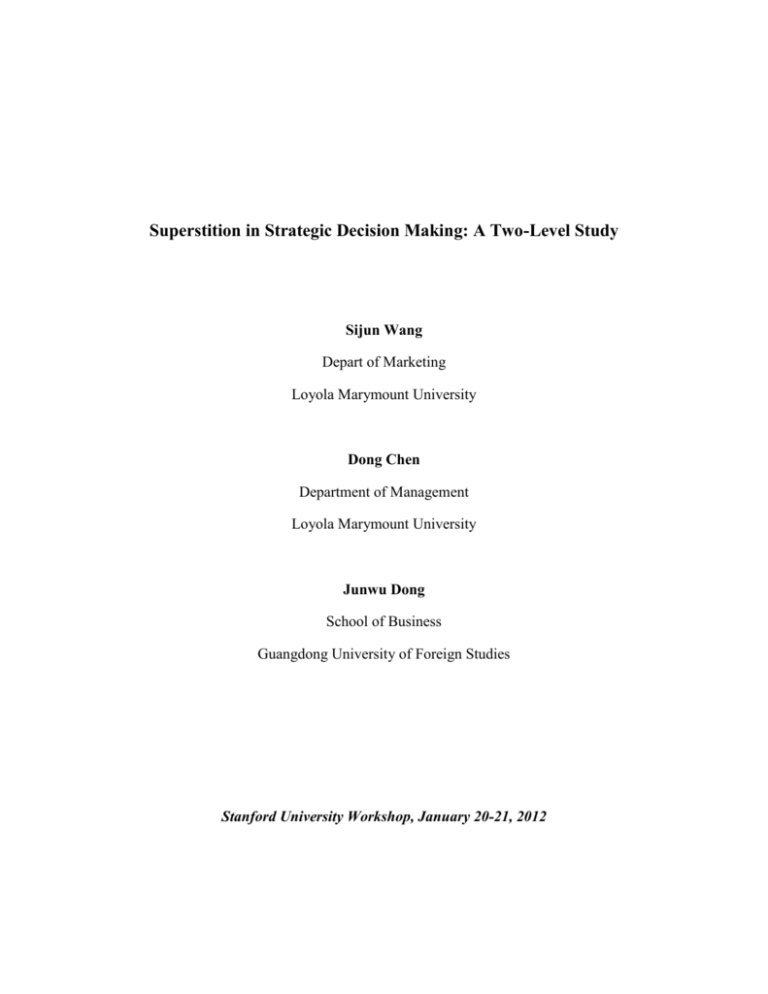

Superstition in Strategic Decision Making: A Two-Level Study Sijun Wang Depart of Marketing Loyola Marymount University Dong Chen Department of Management Loyola Marymount University Junwu Dong School of Business Guangdong University of Foreign Studies Stanford University Workshop, January 20-21, 2012 Superstition in Strategic Decision Making: A Two-Level Study ABSTRACT This study explores the role of superstition in strategic decision making. We propose that, in addition to rational and intuitional approaches, managers sometimes rely on supernatural or nonphysical causality, i.e., superstition. On the personal/decision-maker level, we examine how personal traits are linked to superstitious belief and practice in business decision. On the incident/decision level, we examine how decision characteristics are linked to the use of superstition and consequent decision outcomes. Using a sample of senior managers in China, we confirm the existence of superstition in strategic decision making and its distinctiveness from rationality and intuition. Our findings show that core self-evaluation is negatively related to superstitious belief whilst promotional orientation is positive; mangers are more likely to use superstition when they face important, uncertain, and urgent decisions. Contrary to common knowledge, superstition shows positive impact on decision effectiveness and satisfaction. A rare systematic empirical investigation of superstition in strategic decision making, this study makes important contribution to the management literature. 2 Superstition in Strategic Decision Making: A Two-Level Study 1. INTRODUCTION The decision-making literature has shown that a single cognitive process does not properly describe decision making. Stanovich and West (2002) suggested two decision-making systems, which they labeled as System 1 and System 2. System 1 refers to a process that is described as fast, automatic, effortless, and often emotional. Some scholars roughly equate this system to a decision-maker’s intuition or instincts (Miller and Ireland 2005). In contrast, System 2 is described as slow, controlled, requiring effort, rule-governed, and flexible (Kahneman 2003). System 2 is often typified as a more ―rational‖ decision-making process (Bazerman 2006). Certo, Connelly, and Tihanyi (2008) noted that, for most people, these two processes work together in such a way that System 2 monitors System 1, either confirming or denying intuitive decisions. Nonetheless, intuition and rationality do not seem to encompass the whole picture of decision making. Fuderberg and Levine (2006) argued that some superstitions persist in rational learning. Vasconcelos (2009) proposed that a religious prayer, through religious mechanisms, would enhance and maximize his/her intuitive skills. In other words, supernatural or non-physical beliefs may be intertwined with both System 1 and System 2 decision-making. According to Merrier-Webster dictionary, superstition refers to ―a belief or practice resulting from ignorance, fear of the unknown, trust in magic or chance, or a false conception of causation.‖ Unlike rational thinking, superstition is not based on reason or knowledge. Unlike intuition, which has no evident reference, superstition is usually obtained from outside sources, like tradition or fortunetellers. Superstition can influence various human behaviors and has attracted academic attention from many disciplines. Even in the business research field, where rationality is often an underlying assumption, has started to notice the impact of superstition. 3 Fudenberg and Levine (2006), using a game theory model, confirmed that some superstition can persist under the rationality assumption and persistent superstition does affect human behavior. Finance scholars noticed the impact of superstition on investors, such as how Friday the 13th is linked to stock trading (Kolb and Rodriguez 1987; Lucey 2001). Marketing researchers investigated the impact of superstition on consumer behaviors (Kramer and Block 2008; Carlson, Moven and Fang 2009). Surprisingly, however, despite some anecdotal evidence (Tsang 2004), there is no systematic empirical examination of this phenomenon is management literature. This study intends to systematically examine the concept of superstition in strategic decision making and its impact on decision outcomes. We propose that, in addition to rational and intuitional approaches, managers sometimes rely on supernatural or non-physical causality, i.e., superstition. To understand this silent but critical issue, we apply a two-level study approach to investigate superstition among business decision makers in China. On the personal/decisionmaker level, we examine how personal traits are linked to superstitious belief and practice in business decision. On the incident/decision level, we examine how decision characteristics are linked to the use of superstition and consequent decision outcomes. Compared to rational thinking and intuition, superstition seems to have a distinct role in decision-making. China presents an appropriate setting for this study due to the prevalence and significance of superstition in Chinese societies (Tsang 2004). Although it would be ideal to examine multiple country settings, given the exploratory nature of the study, we believe that a single-country study should be adequate for now. In a pilot study, we first conducted 25 interviews and analyzed critical incidents to establish the concept of superstition in strategic decision making. Then we carefully designed a questionnaire and launched a national survey on strategic decision makers of companies. Using the survey sample of general managers in China, we confirmed the 4 existence of superstition in strategic decision making and found how it is related to personal traits, decision characteristics, as well as decision outcomes. A rare systematic empirical investigation of superstition in strategic decision making, this study makes important contribution to the management literature. 2. THEORY AND HYPOTHESES 2.1 Theoretical Background The decision-making literature has long acknowledged a complementary use of rationalanalytical and experiential-intuitive decision making systems (e.g., Eisenhardt 1989; Eisenhardt and Zbaracki 1992; Agor 1986). The distinction between intuitive and rational thinking is grounded in a foundation of research examining the dual-process nature of social cognition (Evans 2003; Pacini & Espstein 1999; Sloman 1996; Stanovich and West 2000). According the dual-process theories, individuals have two distinct modes of processing and interpreting social information: the rational system, which is responsible for logical and deliberate action and thought, and the experiential system, which is responsible for more intuitive and affect-based responses. Superstitious behavior is thought to be a product of the intuitive system by some researchers (e.g., Epstein et al. 1996; Lindeman and Aarnio 2006). Support for such interpretation can be found in evidence showing individuals will engage in superstitious behavior without actually endorsing belief in the effectiveness of such behaviors (e.g., Bleak and Frederick 1998; Case et al 2004), simply to reduce anxiety and build confidence, among other psychological benefits (Neil 1980; Womack 1979). However, the shared benefits between using intuition and superstitious behavior should be confused with the fundamental conceptual difference between intuition and superstitious systems. We propose that superstition-based 5 approach is conceptually different from the two established analytic and intuitive systems. In particular, the superstition-based approach uses superstitious beliefs, developed through the believers’ ―theory‖ about the world, as cognitive input (Tsang 2004), while intuition has no clear awareness of inputs (Epstein et al 1996) and rationality is based on clear logics (Langley et al 1995). Superstition relies heavily on ―unscientific cause-effect‖ linkages or chance associations (Skinner 1948; Wagner and Morris 1987) while intuition relies on affective information (affectdriven) and rationality on facts. Furthermore, superstition-based decision making has consistent, or even enduring behavior patterns (i.e., that superstition tends to trigger certain type of situational reactions to the environment) while intuition usually has no clear behavior patterns. While both rationality and intuition in strategic decision making have been researched before, there is little understanding about the role of superstition. In order to have a systematic understanding of superstition in strategic decision making, we address a few important questions: Who are likely to use superstition? Why do they do it? When do they do it? How does it affect decision making? To address the who and why questions, we look at the decision makers’ personal traits. Not all managers have superstitious belief and practice. Since decision making is highly personal, the use of superstition is subject to personal characteristics. To answer the when and how questions, we examine the use of superstition in specific incidents of decision making. Superstitious people do not necessarily apply superstition all the time. The use of superstition is also dependent on the features of each decision. The impact of superstition is reflected in the outcomes of individual decisions. 2.2 Conceptual Model I – Personal Level As shown in Figure 1, our conceptual model I was set to answer the first research question— what kind of managers are more likely to possess positive superstitious attitudes and use 6 superstitions in their strategic decision-making. Based on our interviews with 25 CEOs and extensive literature search, we developed a 3M Model-based hierarchical model. The 3M Model (Meta-theoretical Model of Motivation) is a hierarchical account of how personality interacts with situations to influence feelings, thoughts, and behaviors (Carver and Scheier 1990). According to the 3M Model, elemental traits such as the Five-Factors (Saucier 1994) are the most basic components of the personality-motivational structure of the individual. The next level includes compound traits, defined as unidimensional dispositions emerging from the interplay of elemental traits, culture, and the learning history of the individual. The third level of the hierarchy consists of situational traits, which identify tendencies to express consistent patterns of behavior within a general situational context. At the fourth level, surface traits represent the most concrete and context-specific enduring dispositions to behave. -------Insert Figure 1 about here----Following the overall hierarchical structure of 3M Model, we chose to start with the level of compound traits because understanding strategic decision makers’ compound traits would allow for more meaningful managerial implications. In particular, managers’ Core SelfEvaluation (CSE) and their promotional orientation were selected in our Conceptual Model I to represent managers’ self evaluation and future orientation. The logic for investigating these two compound traits will be discussed below. Following Carlson, Mowen and Fang (2009), we treat superstitious beliefs (i.e., attitude toward superstitions) as a situational trait because superstitions tend to occur within certain situations such as situations with high uncertainty. Finally, we conceptualize the general use of superstitions in business decision contexts as a surface trait. Worth to note that our conceptual treatment of general use of superstitions differs from typical surface traits studied in pervious literature on paranormal acts such as wearing good-luck charms 7 and forwarding emails (e.g., Carlson, Mowen and Fang 2009). Paranormal acts in pervious literature typically capture WHAT has been done while our focal construct, general business use of superstitions, focuses on the enduring influence of superstitions across major strategic business decisions. 2.2.1 Core Self-Evaluation Among the fundamental components of decision makers is the basic conviction they have in themselves (Hiller and Hambrick, 2005). Recent psychological research has offered core selfevaluation (CSE), a construct that encompasses four well-studied key concepts: self esteem, self efficacy, emotional stability and locus of control (Judge, Erez, Bono, and Thoresen, 2002). These four concepts share great conceptual similarities and reflect managers’ basic assessment of themselves. The consolidated construct, core self-evaluation, has been empirically validated in a variety of subject samples and proven a parsimonious but strong predictor of human behavior (Judge, Erez, Bono, and Thoresen, 2002). People with high core self-evaluation view themselves positively. They tend to reply on themselves rather than external factors. They are more likely to use their own thinking to make decisions rather than relying on supernatural forces. In a number of non-managerial decisionmaking contexts, researchers have associated an increased tendency to engage in superstitious behavior with low self-esteem and ego-strength (Epstein 1991), low self-efficacy (Tobacyk and Shrader 1991), external locus of control (Tobacyk and Milford 1983), and emotional instability (Epstein 1991; Wiseman and Watt 2004). These relationships suggest that the desire to engage in superstitious behavior is related to a deficit in the ability to maintain self-integrity and self-worth 8 (Moyer 2010). Thus, we hypothesize a negative relationship between a manager’s CSE and his/her attitude toward superstitions. Hypothesis 1: The greater a manager’s core self-evaluation, the more negative his/her attitude towards superstition would be. 2.2.2 Promotional versus Preventional Orientation Essentially, strategic decision making is about predicting the future. Managers’ attitude towards future can play a significant role strategic decision making process. Therefore, we adopted another compound trait—regulatory focus (Higgins 1998) to reflect managers’ motivational orientation toward the future. The term regulatory focus is psychological in origin and refers most broadly to an individual’s tendency to either achieve positive outcomes (promotion focus) or avoid negative outcomes (prevention focus). Previous research on superstitious behavior suggests that employing superstitious actions serves as a means of attempting to influence and control future outcomes under uncertain and risky situations because superstitions provide individuals an illusion of control (e.g., Vyse 1997). In other words, individuals who are more prevention focus would be more likely to resort to superstitious behaviors in order to illusively avoid negative outcomes. Therefore, we believe managers with preventional orientations would be more accommodating of superstitious behavior because acting under the superstitious system could give them an illusion of control through which they could ―prevent‖ negative results. Thus, we propose, Hypothesis 2: The greater a manager’s promotion orientation, the more negative his/her attitude towards superstition would be. 9 2.2.3 Attitude toward Superstitions Borrowing the focal construct of Theory of Planner Behavior, Aact, (TPB, Ajzen 1991), we use attitude toward superstitions to reflect individuals’ general evaluation of superstitions (i.e., superstitious acts). Aact ―refers to the degree to which a person has a favorable or unfavorable evaluation or appraisal of the behavior in question (Ajzen 1991, p.188).‖ We define attitude toward superstitions as cognitive evaluations of engaging in superstitious acts. The strong association between attitude toward an act and intention to act (or actual act) has been repeated reported from different disciplines (c.f., Armitage and Conner 2001). Therefore, we propose: Hypothesis 3: A manager’s attitude towards superstition is positively related to his/her use of superstition in general strategic decision-making. 2.3 Conceptual Model 2 – Incident Level Our conceptual model about the use of superstition at the incident (or decision) level is exhibited in the lower part of Figure 1. Following the Theory of Planner Behavior, we also included the decision maker’s attitude towards superstition at the incident level. Meanwhile, following strategic decision literature (e.g., Bateman and Zeithaml, 1989; Hough and White, 2003; Elbanna and Child, 2007), we considered three key characteristics of strategic decisions: importance, uncertainty, and urgency, and incorporated rationality- and intuition-based approaches in decision making. Furthermore, in order to generate meaningful managerial implications, we examined the impact of superstition by looking at decision effectiveness and satisfaction. 2.3.1 Attitude towards Superstitions 10 Similar to our reasoning for hypothesis 3, we also propose a positive association between a manager’s attitude toward superstitions and his/her use of superstitions in a particular decision making incident. Formally put it, we hypothesize that: Hypothesis 4: A manager’s attitude towards superstition is positively related to his/her practice of superstition in making a strategic decision. 2.3.2 Decision-Specific Characteristics Strategic decision literature has noted the interrelationships between decision-specific characteristics and the decision making process (Rajagopaalan, Rasheed, and Datta, 1993). Among the various factors, the perceived importance of a strategic decision is one of the most influential determinants of decision-making behavior (Papadakis, Lioukas, and Chambers, 1998). Since not all strategic decisions are equally important, managers may apply different approaches. Elbanna and Child (2007) argued that, for both symbolic and functions reasons, executive may count on rationality rather than intuition when facing a highly critical decision. However, such an argument was not empirically supported. In effect, when dealing with an important decision, managers feel a strong need to make it ―right‖ and will use all their means, even superstitious ones, to achieve that objective. This is not to say those managers become irrational or abandon rational approaches. Instead, they try to utilize and combine different decision-making approaches to make the ―right‖ or ―best‖ decision. To some extent, all strategic decisions are important and require certain level of rational thinking. A strategic decision with higher magnitude of impact does not necessarily results in more rationality as the amount is adequate or cannot future increase. Instead, it may push decision makers to seek support from other sources, such as oracles or Feng Shui. Based on the above reasoning, we hypothesize that: 11 Hypothesis 5: The more important a decision, the more likely a manager is to practice superstition in making that decision. Another significant characteristic is the speed needed for decision making (Perlow, OKhuyen, and Repenning, 2002). Especially in recent years, fast speed organizational processes have been widely advocated as a key to success in contemporary business world. Managers are under constant pressure to make quick decisions. While some studies show that individuals under time pressure improve their information processing (Edland, 1994; Kerstholt, 1994), others suggest that performance deteriorates as time pressure increases (Payne, Bettman, & Luce, 1996). The relationship between time pressure and performance is problematic because people react to the sense of urgency differently. Some will rise up to the occasion by utilizing their capabilities and available information. They are likely to view superstition as a complementary information source to infer and justify their decisions. Others will lose their calmness and rationality and resort to experiential learning and superstitious beliefs. It seems whether rationality is enhanced or decreased, time pressure always spur a need for external information. Therefore, the use of superstition is more likely to occur when managers face urgent decisions. Thus, we hypothesize that: Hypothesis 6: The more urgent a decision, the more likely a manager is to practice superstition in making that decision. In addition, the level of uncertainly is also regarded a core characteristic of strategic decision making (Butler, 2002). Unlike many daily activities, strategic decisions are non-routine and always subject to uncertainty. In other words, such decisions are inhibited by limited and ambiguous information (Child, 2002). Without adequate and accurate information, high 12 uncertainty is likely to abate rational thinking. In an empirical study, Dean and Sharfman (1993) found that uncertainty on strategic issues is negatively related to procedural rationality. Consequently, decision makers will have to rely on other decision making approaches, such as experiential learning and superstitious beliefs. Daft and Lengel (1986) argued that high uncertainty would result in a more intuitive decision process. Following a similar logic, we propose decision uncertainly is likely to cause greater use of superstition in strategic decision making. The following hypothesis is advanced: Hypothesis 7: The more uncertain a decision, the more likely the manager is to practice superstition in strategic decision-making. 2.3.3 Decision Outcomes Management scholars have investigated the decisional outcomes of the two established decisionmaking approaches and generally report a positive impact of rationality on decision effectiveness (e.g., Dean and Sharfman 1996; Miller and Cardinal 1994) while the impact of intuition on decision effectiveness remains controversial at most. For example, Khatri and Ng(2000) found that the use of intuition in the strategic decision-making process is negatively related to organizational performance while no influence of intuition was reported by Elbanna and Child (2007). Reconciling the inconsistent findings, Elbanna and Child (2007) suggest that strategic decision effectiveness is both process- and context-specific and culturally bound. However, up to date, there is no research involving the impacts of use of superstition on decision effectiveness. Our in-depth interviews and the psychology literature (e.g., Vyse 1997) lead us to propose a positive relationship between use of superstitions and decision effectiveness. Our argument is based on two logics. First, the number of psychological benefits of superstitions, 13 including reducing anxiety and stress with unknown, uncertain, and risky environment, would enable managers to concentrate on sensing-making of the known and certain environmental factors. Through a series of psychological experiments, Damisch, Stoberock, and Mussweiler (2010) found that superstition boosts participants’ confidence in mastering upcoming tasks, increases individual persistence, and thus improve performance. The peace of mind brought by superstition would not only improve decision makers’ psychological status but also actually enhance decision effectiveness. Second, our interviews revealed that use of superstitions in the strategic decision-making context tends to be proactive, rather than passive, in nature. For example, one CEO in our qualitative study called geomancers to determine whether a building or office faces in the correct direction to attract good ―chi‖ (environmental force). Similar proactive superstitious acts during business decision-making have also been reported in the literature (e.g., Zetlin 1995; Tsang 2004). Such proactive (or positive) superstitions serve as ―positive illusions‖ to motivate firmer implementations of the decision than otherwise, thus leading to a more coordinated organizational effort toward carrying out the decision. The above discussion leads us to hypothesize the following: Hypothesis 8: A manager’s practice of superstition is positively related to his/her satisfaction towards the decision process. Hypothesis 9: A manager’s practice of superstition is positively related to with the effectiveness of the decision. 2.4. Control Variables We exercise caution in regards to possible spurious and attenuating variables that could influence our proposed relationships by incorporating a number of relevant covariates—manager 14 demographics (age, gender, and education), manager’s religions, organizational characteristics (industry, company ownership, company investor structure, size, and organizational age), and decision types. The list of these covariates was based on our extensive survey of different literature and was judged on the likelihood of potential impacts of these covariates on our focal relationships. For example, organizational age was selected because some research suggests that different organizational life cycle stage would moderate the impacts of management style on company performance (e.g., Brettel, Engelen, and Voll 2010). 3. METHODS 3.1. Sample and Survey Administration The sample consists of senior managers from three industries across five major metropolitan areas in China. To ensure respondents’ strategic decision-making roles, our field research assistants, via telephone, first qualified each respondent’s participation in his or her organization’s strategic decision-making process; they then checked on each respondent’s organizational position selected only those who held positions of general manager, vice general manger, and senior managers. Our field research assistants then visited each qualified respondent’s office and administered the survey through paper and pencil format. During the whole data collection process, we carefully monitored the distribution of respondents across regions, industries, and organizational size, among other contextual variables in order to lessen potential sampling biases. Within the data collection period of two months, we accumulated 353 useable surveys. We were able to obtain 270 respondents who had recently (in the past six months) experienced the influence of superstitions in their recent strategic decisions while 183 indicated that they had not experienced the influence of superstitions in their past decisions. All 353 respondents were 15 distributed across five regions (Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Xi’An, and Wenzhou) in a roughly even fashion. 112 of them work at manufacturing industry (31.7%), 74 at restaurant industry (21.0%), and 146 at professional service industries (41.4%). We have also had reasonable variety of respondents from state-owned enterprises (27.6%) to privately-invested companies (72.4%), from publicly-traded companies (16.4%) to privately-held ones (83.6%), from small to big companies in terms of their employee numbers, revenue, and assets (our sampled organizations’ size spread out as a normal distribution curve). In addition, we checked the positions / job titles of all respondents and found that all respondents held at least ―senior manager‖ or equivalent job titles in their organization, with almost half of them (48.4%) holding position of General Manager (CEO), thus composing a valid informant group for our study purpose. Respondents’ personal profiles also reflected the target population’s profile; their average age was 37.7 years old and more educated then general population (77.5% of them had some college education or higher). We also had slightly more male respondents (66.3%) than females (33.7%). 3.2 Measures Appendix provides the operationalization and descriptive statistics and reliability indices for the study’s constructs. The scales used to measure superstitious attitudes, general influence of superstition in strategic decision-making, and use of superstition in one specific decision-making were self-developed based on both the decision-making theory literature and extensive interviews with 25 CEOs from our pilot study prior to the main survey. The rest of scales were largely adopted from existing literature, with consideration of parsimony of number of items per construct given our sample respondents’ nature. While most items in the Appendix A are multiple items, one item in particular should be explained. Our operationalization of general 16 influence of superstition in strategic decision-making is a single item measure aimed at obtaining the respondent’s perceived overall influence of superstition in five types of strategic decisions in the organization, including decisions about major strategic moves, location and relocation decisions (e.g., office building’s orientation), timing (e.g., opening dates, opening ceremony dates), major investment decisions, recruitment of key senior managers, and other strategic decisions. These five major types of strategic decisions were selected based on our pilot interviews with 25 CEOs and they were most frequently mentioned as being influenced by superstitions. As Bagozzi and Heatherton(1994) suggest, when dealing with a large number of scales and items, large scales can be disaggregated into subscales and the composites of the subscales treated as indicators. Thus, we conceptualize senior managers’ Core Self Evaluation (CSE), composed of locus of control, emotional stability, self-esteem, and self-efficacy, as higher-order factors. Treating CSE as second order constructs is justifiable conceptually. First, this construct is super-ordinate concepts, meaning they are general concepts manifested by their subdimensions. Further, aggregating their sub-dimensions in our second-order model also matches their levels of abstraction with those of other concepts in the model (Edwards 2001). 4. RESULTS 4.1 Measurement Model Analysis Table 1 provides means and pairwise correlations of our main constructs and the reliability coefficients for multiple-item constructs. Measurement reliability and validity for our conceptual model one were assessed by estimating a confirmatory factor measurement model, where CSE as second-order construct, promotional orientation, attitude toward superstitions, general influence of superstition in strategic decisions, and other control variables such as religion and past 17 behavior of engaging in superstitious acts were included. In the model, each item was set to load only on its own factor, and the factors were allowed to correlate. All fit indices except the chisquare statistic (Chi-square with 42 degrees of freedom =173.52, p<.01) indicate support for the hypothesized model (CFI =.98, NFI=.97, IFI=.98, SRMR=.033; Bollen 1989). These results indicate the uni-dimensionality of the measures (Anderson and Gerbing 1988). Further, all factor loadings were statistically significant (p <.01) and the composite reliabilities of each construct all exceeded the usual .60 benchmark (Bagozzi and Yi 1988). Thus, these measures demonstrate adequate convergent validity and reliability. Moreover, all the cross-construct correlations were significantly smaller than |1.00| (p<.01), signifying the discriminant validity of these measures (Phillips 1981). Similarly, the measurement model of our conceptual model 2 was also assessed with the same confirmatory factor modeling procedure. In this measurement model, nine constructs including satisfaction with the decision, perceived effectiveness of the decision, use of superstitions, use of rationality, use of intuition, attitude toward superstitions, and perceived importance, uncertainty, and urgency of the decision were included. Again, all fit indices except the chi-square statistic (Chi-square with 360 degrees of freedom =750.45, p<.01) indicate support for the hypothesized model (CFI =.98, NFI=.97, IFI=.98, SRMR=.048; Bollen 1989). -------Insert Table 1 about here----4.2 Control Variables Besides the key variables of interest in our conceptual model, we took the precaution of controlling for possible effects caused by three categories of variables. These were variables to ascertain the respondent’s personal characteristics (e.g., age, gender, education), variables to establish the characteristics of the respondent organization (e.g., industry, ownership type, size, 18 private versus state-owned), and variables concerning the nature of one specific decision (e.g., types of decisions). See Appendix for the items used to measure these covariates. The covariates were chosen based on our extensive literature review and pretests with various organizations before the commencement of the main study. To control for the potential effects of respondents’ personal characteristics, we first regressed all items measuring attitude toward superstitions on respondents’ age, gender, and education levels, obtained the residuals (i.e., the items with covariate effects parceled out), and then used these residuals in testing our hypotheses. We also have controlled the potential impacts of organizational characteristics by regressing the general influence of superstitions in strategic decisions on organizational size, industry, organizational age, and ownership type. Further, we controlled the potential impacts of decision types and organizational characteristics by regressing satisfaction with the decisions, perceived effectiveness of the decision, use of superstition, use of rationality, and use of intuition on five covariates, including organizational size, industry, ownership type, organizational age, and decision types. Our examination of all regression results lead us to the conclusion that some covariates could have disguised the true relationships among our key constructs had they not been parceled out through our laborious regression analyses. The detailed impacts of these significant covariates on both dependent and independent variables are beyond the scope of our present theoretical essay, but are available upon request. 4.3 Common Method Bias and Non-Response Bias Assessments Because we collected information on dependent and independent variables from the same respondent, our study was potentially subject to common method bias. To assess any effects of common method variance on the results, we used procedures recommended by Williams and Anderson (1994) and Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, and Podsakoff (2003). We added a ―method‖ 19 factor where all indicators for all latent variables loaded on this factor, and on their respective latent variable in our measurement model. In our test for common method bias, two models were compared: one in which all the paths from the common factor were fixed at zero, and one in which the method factor was freed. Several indicators were found to load on the method factor, but the structural results were completely consistent with the results reported (given the large number of indicators). Detailed common method results are not presented here, but are available upon request. Further, Armstrong and Overton (1977) recommend that non-response bias be assessed by comparing the responses of early respondents with those of late respondents. Accordingly, a comparison of the first ten percent of the respondents with the last ten percent of respondents for all key constructs was conducted. The mean differences between these groups for each of the focal constructs are insignificant, providing evidence that non-response bias is not a concern. 4.4. Results 4.4.1 Testing Model 1 We derived the full structural model from our hypotheses (H1-H3) based on the conceptual model 1 presented in Figure1. Table 2 presents the standardized path coefficients for all relationships in the structural model. As shown in Table 2, our data support the proposed model ( =196.19, d.f.=48, p<.01; CFI=.97, IFI=.97, NNFI = .96, and SRMR=.052). The hypothesized 2 model explains 45% of the variance in the general influence of superstitions in strategic decisions, and 68.3% of respondents’ attitude toward superstitions. Note all three hypotheses were supported by our data. Specifically, Hypothesis 1 predicting managers’ CSE to be negatively related to their attitude toward superstitions. This hypothesis was supported (β=-.21, p <.05). Hypothesis 2, stating that managers with higher promotional orientations are more 20 negative toward superstitions, was not supported. Unexpectedly, the standardized path was positive and significant (β= .51, p <.001), suggesting that promotion-orientated managers are more positive towards superstition. Finally, Hypothesis 3, suggesting a positive relationship between managers’ attitude toward superstitions and general influence of superstitions in their strategic decision making, was supported (β=-.67, p <.001). ---Table 2 About Here--4.4.2 Testing Model 2 We derived the full structural model from our hypotheses H4-H9 based on the conceptual model 2 presented in Figure 1. To discriminate the nomological nature of use of superstitions from two recognized decision-making approaches in the previous literature —use of rationality and use of intuition, we have also added use of rationality and use of intuition to the model and added unhypothesized paths from three contextual variables of the decision (i.e., the perceived importance, uncertainty, and urgency) to these two decision approaches. We further added the links from these two approaches to both satisfaction with the decision and perceived effectiveness of the decision. These added paths were shown in dotted lines in the Figure. Table 2 presents the standardized path coefficients for all relationships in the structural model. As shown in Table 2, our data support the proposed model ( =609.86, d.f.=377, p<.01; CFI=.99, 2 IFI=.99, NNFI = .99, and SRMR=.067). The hypothesized model explains 53.7% of the variance in respondents’ satisfaction with their decisions, and 34.3% of respondents’ perceived effectiveness of the decision. Our model could also explain an impressive portion of respondents’ use of superstitions when making one specific strategic decision (65.9%). All our six hypotheses were supported by our data, as shown in Table 2. 21 4.4.3 Follow-up Analyses Recall that we have added ten paths to discriminate the nomological nature of use of superstitions from the use of rationality and intuition when analyzing the structural model 2. We found that these three decision-making approaches had different antecedent sets as well as different effect sizes of their impacts on decision outcomes as measured by satisfaction with the decision and the perceived effectiveness of the decision. Specifically, we found that managers tended to use more superstitions when a particular decision was important, urgent, and with a higher uncertainty. However, managers increased their use of rationally only when a particular decision was urgent. In terms of intuition, managers increased its use when a particular decision was urgent and with a higher uncertainty while no difference of use of intuition was found due to importance of the decision, echoing findings from previous research on managerial intuition (Agor 1986; Anderson 2000; Kuo 1998). We then conducted nested SEM models where the paths corresponding to the impacts of use of superstitions versus those of use of rationality and intuition were constrained to be equal sequentially. The resulting χ2 differences with 1 degree of freedom between each constrained model and its associated freely estimated model were then analyzed. We found that use of superstition had significantly weaker impact on satisfaction than use of rationality (βuseofsuperstition =.16 versus βuseofrationality =.39; ∆χ2=8.40, p=.003), but no difference from use of intuition (βuseofsuperstition =.16 versus βuseofintuition =.15; ∆χ2=.40, p>.10). However, we found no differential impacts of three decision approaches on perceived decision effectiveness. In sum, we found that use of superstitions had different set of antecedents from those of use of rationality and intuition and it has differential impact on decision satisfaction from use of rationality. Therefore, our follow-up analyses seemed to suggest the nomological difference of 22 use of superstitions from other two established decision approaches. In combination with the measurement discrimination of these three decision approaches, our follow-up analyses further support the discriminate validity of use of superstitions. 5. DISCUSSION There is a scarcity of empirical research on managers’ use of superstitions in their strategic decision-making even though the prevalence of superstitious behavior in contemporary organizational decision-making processes was widely acknowledged, especially in East Asian region (e.g., Tsang 2004). Our research sets to contribute to the decision-making literature by acknowledging a new approach of decision-making—use of superstitions—as a supplementary approach to the two established decision-making approaches (i.e., use of rationality or analytical approach, and use of intuition or intuitive approach) and by systematically studying the antecedents and impacts of the use of superstitions. We first conducted in-depth interviews with 25 CEOs to document the existence of influence of superstitions in five types of strategic decisions, including decisions about major strategic moves, location and relocation decisions (e.g., office building’s orientation), timing (e.g., opening dates, opening ceremony dates), major investment decisions, and recruitment of key senior managers. Besides empirically ―announcing‖ the existence of this new decision-making approach, we further developed conceptual model I to understand what kind of managers (WHO) tend to possess more positive attitude toward superstitions and how much impacts of such attitude on managers’ strategic decisions. Furthermore, we developed conceptual model II to explain and predict what kind of strategic decisions (WHEN) tend to motivate managers to use superstitions and HOW the use of superstitions influences managers’ satisfaction with the decision and perceived effectiveness of 23 the decision. Results from surveying with 353 senior managers in China largely supported our two conceptual models, leading to the following theoretical contributions to the decision-making literature. First, our research represents the first systematic exploration into antecedents and impacts of use of superstitions in strategic decision-making. Conceptualization of the use of superstitions in strategic decision making process enriches the current management literature not only for its newness, but also for its incremental contribution to building an integrative model of the strategic decision-making process. Our conceptual differentiation of three decision-making approaches was empirically supported. We found the complementary use of rationality, intuition, and superstitions in a single decision-making situation. The three decision-making approaches had different sets of antecedents and different impacts on the decision outcomes. Recall that we found that managers tended to use more superstitions when a particular decision was important, urgent, and with a higher uncertainty. However, managers increased their use of rationally only when a particular decision was urgent. In terms of intuition, managers increased its use when a particular decision was urgent and with a higher uncertainty while no difference of use of intuition was found due to importance of the decision. Secondly, our research achieved high explanatory power by linking managers’ two personal traits—promotional orientation and CSE—to their attitude toward superstitions. We found that managers with a lower CSE tend to be more superstitious than those with a higher CSE. Another interesting finding of our study was that we found mangers with promotion focus, rather than with prevention focus, tend to hold more positive attitude toward superstitions, which is in contrast to what existing literature would suggestion. We believe this surprising finding could be rooted in the different cultural attitude toward ambiguity. Decision-makers in Western 24 culture tend to seek for all of the facts and variables and view ambiguity as a threat to their decision-making process (e.g., Budner 1962). Therefore, they tend to use superstitions as a preventional approach. In Oriental cultures, mangers tend to make peace with ambiguity in their external environment, thus, might not have a strong need to resort to superstitions to avoid negative outcomes (Pascale 1978; Tse et al 1988). Instead, individuals with high tolerance for ambiguity, as our target respondents from Chinese culture, were found to frequently engage in promotional superstitions such as auction for lucky numbers for license plates (e.g., Woo et al 2008). Thirdly, our research also successfully predicted when managers resort to superstitions through our Conceptual Model II. Results of this conceptual model suggest that mangers’ personal attitude along with a decision’s contextual factors jointly encourage or discourage the use of superstitions in strategic decision making. More specifically, when a superstitious manager faces an important, uncertain, and urgent strategic decision, he would be more likely to use superstitions. Finally, our research provides an integrative view of the strategic decision-making process and its link with decision outcomes. By proposing the third decision-making approach, we offer a better understanding of strategic decision-making processes. Combining different perspectives of decision-making when investigating the strategic decision-making process has been advocated by several scholars (e.g., Bateman and Zeithaml 1989; Shneider and Meyer 1991). However, due to the Western dominant research contexts, use of superstitions has received little attention. Our survey with Chinese managers indicated a strong need for understanding this unique decision-making approach. Our results suggest that use of superstitions and use of intuition in strategic decision-making process had comparable impacts 25 on managers’ satisfaction with the decision and the perceived effectiveness of the decision. The use of superstitions and use of rationality also share comparable impacts on the perceived effectiveness of the decision. 6. LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH As do all studies, ours has limitations. First, we only administered surveys with managers from Mainland China. Even though our research design lessened the possible macro-cultural impacts on our hypothesized relationships should we have surveyed managers from different nations or regions, the external validity of our findings remain untested. Echoing several researchers on Chinese consumer superstitions, we naively believe that how superstitions affect managers’ decision making might not be unique to Chinese managers. As stated by Woo et al. 2007, p. 50), ―The Chinese, who are not born superstitious, are by no means unique.‖ However, until further research was conducted with mangers from different cultural and economic backgrounds, the boundary of our conceptual framework remains unknown. We encourage more applications of our framework to different samples. Second, we collected data from managers via single-informant self-reports of past incidents. Despite our rigorous efforts to carefully pre-screen respondents by checking their involvement and knowledge regarding strategic decision making, future studies certainly would benefit from soliciting information from multiple informants at each respondent organization as well as from different sources of information to assess the organizational outcome of use of superstitions. For instance, we measured decision effectiveness with the manager’s self-reported perception, thus subject to bias. In addition, we asked managers to recall past incident in the survey. The accuracy of past experience could be questioned. Other research approaches to this topic of inquiry might yield 26 interesting results. For example, experimental design and decision-making simulation would seem highly appropriate for examining this complex research topic. We thus encourage future efforts to examine this area from a variety of research methods. In closing, our results provide robust support for our proposed models, which fundamentally explains who, when, and how questions relate to use of superstitions in managers’ strategic decision-making. We hope that our inquiry inspires other researchers to investigate these domains and thereby enlarge the understanding of business use of superstitions. 27 Table 1 Correlations and Descriptive Statistics Variables Model I (N=353) 1.Promotional Orientation 2.Locus of Control 3.Emotional Stability 4. Self-Esteem 5. SelfEfficacy 6. General Business Use 7. Religion 8. Attitude toward Superstitions Model II (N=270) 9.Importance 10. Urgency 11. Uncertainty 12. Use of Superstitions 13. Use of Rationality 14. Use of Intuition 15. Satisfaction 16. Effectiveness M SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 0.80 0.95 11 12 13 14 15 16 0.67 0.33 0.91 0.39 0.84 0.52 0.67 0.40 0.95 0.68 0.73 0.44 0.51 0.89 0.39 0.42 0.58 0.43 0.39 0.87 0.36 0.34 0.41 0.16 0.47 0.29 0.86 0.39 0.41 0.52 0.40 0.41 0.68 0.41 0.86 0.43 0.48 0.47 0.38 0.36 0.64 0.36 0.64 0.85 4.60/4.99* 1.54/1.20* 4.75 1.57 4.84 1.46 4.95 1.43 4.52 1.57 5.28 1.10 4.59 1.34 5.42 1.03 5.20 1.15 0.75 0.59 0.87 0.61 0.75 0.87 0.70 0.75 0.84 0.90 0.77 0.69 0.70 0.82 0.87 0.24 0.22 0.19 0.22 0.20 0.27 0.27 0.25 0.24 0.21 0.59 0.39 0.33 0.31 0.36 0.36 0.64 5.59 1.25 5.39 1.25 5.31 1.19 5.60 1.16 5.77 1.11 3.49 1.89 4.60 1.54 * The first number of Mean and Stand Deviation of attitude toward superstitions was for the total 353 respondents and the second numbers were for the 270 respondents who had recently experienced the influence of superstitions in their strategic decision making. 28 Table 2 Results of Hypothesized Relationships in Model I & Model II Hypothesized Relationships Model I H1: CSEAttitude toward Superstitions H2: Promotional OrientationAttitude toward Superstitions H3: Attitude toward SuperstitionsGeneral Business Use Model II H4: Attitude toward SuperstitionsUse of Superstitions H5: Importance of decisionUse of Superstitions H6: Urgency of decisionUse of Superstitions H7: Uncertainty of decision Use of Superstitions H8: Use of SuperstitionsSatisfaction H9: Use of SuperstitionsEffectiveness Additional Paths ImportanceUse of Rationality UrgencyUse of Rationality UncertaintyUse of Rationality ImportanceUse of Intuition UrgencyUse of Intuition UncertaintyUse of Intuition Use of RationalitySatisfaction Use of IntuitionSatisfaction Use of RationalityEffectiveness Use of IntuitionEffectiveness *p<=.05; **p<.01; ns=not significant. 29 Standardized Path Coefficient Estimate TValue -.21* .51** -2.06 4.69 .67** 15.31 .35** 4.13 .61** .12* .22** .16** .23** 5.62 1.96 2.90 2.36 5.40 .11ns .34** .061ns .16ns .46** .24* .39** .15* .37** .24** 1.13 4.44 .065 1.62 5.91 2.55 6.26 2.47 5.58 5.40 Figure 1 Conceptual Models of Managers’ Use of Superstitions in Strategic Decision Making Self esteem Religions Self efficacy Core Self Evaluations H1 Attitude toward Superstitions Emotional Stability Locus of control H3 + General Business Use H2 Promotional Orientation Model I: Predicting Attitude toward & General Business Influence of Superstitions Attitude toward Superstitions H4 + H5 + Importance of Decision Use of Superstitions H8 + Satisfaction with Decision H6 + H7 + Use of Rationality Urgency of Decision Use of Intuition H9 + Perceived Effectiveness of Decision Uncertainty of Decision Model II: Predicting Use of Superstitions in Strategic Decision-Making 30 Appendix Construct and Source Items (Description)* Factor Loading Core Self- Evaluations (Second-order Construct) Locus of Control (Levenson 1974) Emotional Stability (Goldberg 1999) Self Esteem ( Bearden and Rose 1990) .81 1. I am pretty much determined what will happy in my life. 2. When I make plans, I am almost certain to make them work. 3. When I get what I want, it’s usually because I worked hard for it. .87 1. I seldom feel blue. 2. I feel comfortable with myself. 3. I readily overcome setbacks. 4. I am relaxed most of the time. .95 1. On the whole, I am satisfied with myself. 2. I feel that I have a number of good qualities. 3. I feel that I am a person of worth, at least on a equal plane with others. 4. I take a positive attitude toward myself. Self Efficacy (Sherer et al 1982) .87 1. I am confident in my ability to perform the functions of my job. 2. When I make plans, I am certain I can make them work. 3. When I can’t do a job first time, I keep trying until I can. Promotional Orientation (Lockwood, Jordan and Kunda 2002) 1. In general, I am focused on achieving positive outcomes in my life. 2. Overall, I am more oriented toward achieving success than preventing failure. .79 .76 Attitude Toward Superstitions (self-developed) 1. It won’t hurt to follow superstitious rituals. 2. I would rather trust superstitions than not for the risk of not trusting is simply too big. 3. Superstitious rituals / acts serve as a sort of “spiritual help.” .87 Religiousness (Torgler 2007) Would you describe yourself as 1.Extremely non-religious….7.Extremely religious General Business Influence of Superstitions (Self-developed) How would you rate the influence of superstitions on the following decision areas of your company (1 low….7 high) 1. Developmental directions (e.g., merger & acquisition, trade names) 2. Location decisions (e.g., Location of office buildings, facing direction of offices) 3. Timing decisions (e.g., opening dates, ceremony dates) 4. Investment & major purchase decisions (e.g., stock investment) 5. Recruitment of senior managerial personnel (e.g., hiring & promotions for senior positions) 6. others (please specify__________) Decision Importance (selfdeveloped) 1. How important was the decision you described above to your company performance? 2. How important was the decision you described above to your personal career. 1.not important at all…….7. extremely important Decision Uncertainty (Selfdeveloped) How would you rate the uncertainty of the decision in terms of … 1. actions to be taken. 2. general directions to go. 3. the information to be collected. 31 .83 .84 .90 .87 .86 .83 .81 Decision Urgency (selfdeveloped) 1. For the decision I described above, I was pushed to make a final decision as soon as possible. 2. The decision I described above was high on the agenda for my company. .92 .95 Use of Superstitions (selfdeveloped) 1. I have followed advices given by experts in superstitious rituals (e.g., Fengshu Master, Monks, Daosi, etc.) in my decision. 2. I have incorporated superstitious ideas in my decision. 3. Beliefs and ideas based on superstitions (e.g., Fengshui, Mianxiang, Oracle) have helped me a great deal in making my decision. .86 Use of Rationality (Sinclair, Ashkannasy, and Chattopadhyay 2010) 1. I evaluated systematically all key uncertainties. 2. I made the decision in a logical and systematic way. 3. I considered all consequences of my decision. 4. I considered carefully all alternatives. .68 .80 .83 .75 Use of Intuition (Sinclair, Ashkannasy, and Chattopadhyay 2010) 1. I based the decision on my inner feelings and reactions. 2. I relied on my instinct. 3. It was more important for me to feel that the decision is right than have a rational reason for it. .65 .90 .82 Decision Satisfaction (Oliver 1993) 1. I am satisfied with my decision. 2. I am sure my decision was the right one. 3. The decision was as good as I expected. .70 .83 .78 Decision Effectiveness (Dooley and Fryxell 1999) 1. The decision helps my organization achieve its objectives. 2. The decision makes sense in light of my organization’s current financial situaiton. 3. The decision contributes to the overall effectiveness of my organization. .60 .88 .87 *Unless indicated otherwise, all items were measured with 7-Point Likert scales. 32 .91 .90 REFERENCES Ajzen, Icek (1991), "Perceived Behavioral Control, Self-Efficacy, Locus of Control, and the Theory of Planned Behavior," Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32 (4), 665-683. Armitage, Christopher J. and Mark Conner (2001), "Efficacy of the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A Meta-Analytic Review," British Journal of Social Psychology, 40 471-499. Bagozzi, Richard P. and Todd F. Heatherton (1994), "A General Approach to Representing Multifaceted Personality Constructs: Application to State Self-Esteem.," Structural Equation Modeling, 1 (1), 35-67. Bateman TS, Zeithaml CP. 1989. The psychological context of strategic decisions: a model and convergent experimental findings. Strategic Management Journal 10(1): 59–74. Bateman, T.S. and C. P. Zeithaml (1989), "The psychological context of strategic decisions: a model and concergent experimental findings," Strategic Management Journal, 10 (1), 59-74. Bazerman, Max H. (2006), Judgment in managerial decision making. Hoboken, NJ: John Wile & Sons. Bleak, J. L. and C. M. Frederick (1998), "Superstitious behavior in sport: Levels of effectiveness and determinants of use in three collegiate sports," Journal of Sport Behavior, 21 1-15. Brettel, Malte, Andreas Engelen and Ludwig Voll (2010), "Letting go to grow--Empirical findings on a Hearsay," Journal of Small Business Management, 48 (4), 552-579. Budner, S. (1962), "Intolerance of Ambiguity as a Personality Variable," Journal of Personality, 30 29-50. Butler R. 2002. Decision making. In Organization, Sorge A. (ed). Thomson Learning: London; 224–251. Carlson, Brad D., John C. Mowen and Xiang Fang (2009), "Trait Superstition and Consumer Behavior: Re-Conceptualization, Measurement, and Initial Investigations," Psychology & Marketing, 26 (8), 689-713. Carver, C. S. and M. F. Scheier (1990), "Origins and functions of positive and negatie affect: A control-process view," Psychological Review, 97 19-35. Case, T. I., J. Fitness, D. R. Cairns and R. J. Stevenson (2004), "Coping with uncertainty: Superstitious strategies and secondary control," Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34 848871. Certo, S. Trevis, Brian L. Connelly and Laszlo Tihanyi (2008), "Managers and their not-so rational decisions," Business Horizons, 51 113-119. 33 Child J. 2002. Strategic choice. In Organization, Sorge A. (ed). Thomson Learning: London; 107–126. Daft RL, Lengel RH. 1986. Organizational information requirements, media richness and structural design. Management Science 32(5): 554–571. Damisch, L., Stoberock, B., and Mussweiler, T. 2010. Keep your fingers crossed! How superstition improves performance. Psychological Science, 21(7): 1014-1020. Dean JW, Sharfman MP. 1993. Procedural rationality in the strategic decision-making process. Journal of Management Studies 30(4): 587–610. Dean, J. W. and M. P. Sharfman (1996), "Does decision process matter? A study of strategic decision-making effectiveness " Academy of Management Journal, 39 (2), 368-396. Edland, A. 1994. Time pressure and the application of decision rules-Choices and judgments among mul-tiattribute alternatives. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 35: 281-291. Edwards, Jeffrey R. (2001), "Multidimensional Constructs in Organizational Behavior Research: An Integrative Analytical Framework," Organizational Research Methods, 4 144-192. Elbanna, Said and John Child (2007), "Influences on Strategic Decision Effectiveness: Development and Test of an Integrative Model," Strategic Management Journal, 28 431-453. Epstein, S. (1991), "Cognitive-experiential self theory: Implications for developmental psychology," in Minnesota Symposia on Child Psychology: Self-Processes and Development, 23, M. Gunnar and L. A. Stroufe, eds. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, 79-123. Epstein, S., R. Pacini, V. Denes Raj and H. Heier (1996), "Individual differences in intuitiveexperimential and analytical-rational thinking styles," journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71 390-405. Evan, J. S. B. T. (2003), "In two minds: Dual-process accounts of reasoning," Trends in Cognitive Science, 7 454-459. Fudenberg, Drew and David K. Levine (2006), "Superstition and Rational Learning," American Economic Review, 96(3): 630-651. Fudenberg, Drew and David K. Levine (2006), "Superstition and Rational Learning," Harvard Institute of Economic Research Discussion Paper, No. 2114 Hough JR, White MA. 2003. Environmental dynamism and strategic decision-making rationality: an examination at the decision level. Strategic Management Journal 24(5): 481–489. 34 Kahneman, Daniel (2003), "A perspective on judgment and choice," American Psychologist, 58 (9), 697-720. Kerstholt, J. H. 1994. The effect of time pressure on decision-making behavior in a dynamic task envi-ronment. Acta Psychologica, 86: 89-104. Khatri, N. and H. A. Ng (2000), "The role of intuition in strategic decision making," Human Relations, 53 (1), 57-86. Kolb, Robert W. and Ricardo J. Rodriguez (1987), "Friday the Thirteenth: "Part VII": A note," Journal of Finance, 42 (5), 1385-1387. Kramer, T. and Block, L. (2008), Conscious and nonconscious components of superstitious beliefs in judgment and decision making. Journal of Consumer Research, 34(6), 783-793. Lindeman, M. and K. Aarnio (2006), "Paranormal beliefs: Their dimensionality and correlates," European Journal of Personality, 20 585-602. Lucey, B.M. (2001). ―Friday the 13th: international evidence‖, Applied Economics Letters, 8, 577–579. Miller, C. C. and R.D. Ireland (2005), "Intuition in strategic decision making: Friend or foe in the fast-paced 21st century?," Academy of Management Executive, 19 (1), 19-30. Miller, D. and L. B. Cardinal (1994), "Strategic planning and film performance: a synthesis of two decades of research," Academy of Management Journal, 37 1649-1665. Neil, G. (1980), "The place of superstition in sport: The self-fulfilling prophecy," Coaching Review, 3 40-42. Pacini, R. and S. Epstein (1999), "The relation of rational and experiential information processing styles to personality, basic beliefs, and the ratio-bias phenomenon," Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76 972-987. Pascale, Richard T. (1978), "Zen and the art of management," Harvard Business Review, March/April 153-162. Payne, J. W., Bettman, J. R., & Luce, M. F. 1996. When time is money: Decision behavior under opportuni-ty-cost time pressure. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 66: 131-152. Perlow, Leslie A., Okhuysen, Gerardo A., and Repenning, Nelson P. 2002. The Speed Trap: Exploring the Relationship between Decision Making and Temporal Context. Academy of Management Journal, 45(5): 931-955. 35 Saucier, G. (1994), "Mini-markers: A brief version of Goldberg's unipolar big five markers," Journal of Personality Assessment, 63 506-516. Schneider, S.C. and De Meyer, A. D. (1991), "Interpreting and responding to strategic issues: the impact of national culture," Strategic Management Journal, 12 (4), 307-320. Skinner, B. F. (1948), ""Superstition" in the pigeon," Journal of Experimental Psychology, 38 168-172. Sloman, S. A. (1996), "The empirical case for two systems of reasoning," Psychological Bulletin, 119 3-22. Stanovich, K. E. and R. F. West (2000), "Individual differences in reasoning: Implications for the rationality debate?" Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 23 645-726. Tobacyk, J. and D. Shrader (1991), "Superstition and self-efficacy," Psychological Reports, 68 1387-1388. Tobacyk, J. and G. Milford (1983), "Belief in paranormal phenomena: Assessment instrument development and implications for personality functioning," journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44 1029-1037. Torgler, Benno (2007), "Determinants of superstiton," The Journal of Socio-Economics, 36 713733. Tsang, Eric W.K. (2004), "Superstition and Decision-making: Contradiction or Complement?" Academy of Management Executive, 18 (4), 92-104. Tse, David K., Kam-hon Lee, Ilan Vertinsky and Donald A. Wehrung (1988), "Does culture matter? a cross-cultural study of executives' choice, decisiveness, and risk adjustment in international marketing," Journal of Marketing, 52 81-95. Vasconcelos, Anselmo Ferreira (2009), "Intuition, prayer, and managerial decision-making processes: a religion-based framework," Management Decision, 47 (6), 930-949. Vyse, S. A. (1997), Believing in magic: The psychology of superstition. New York: Oxford University Press. Wagner, G. A. and E.K. Morris (1987), "‘Superstitious’ behavior in children," Psychological Record, 37 471-488. Williams, Kaylene C. and Rosann L. Spiro (1985), "Communication Style in the SalespersonCustomer Dyad," Journal of Marketing Research, 22 (4), 434-442. 36 Wiseman, R. and C. Watt (2004), "Measuring superstitious belief: Why lucky charms matter," Personality and Individual Differences, 37 1533-1541. Womack, M (1979), "Why athletes need ritual: As study of magic among professional athletes," in Sport and the Humanities: A Collection of Original Essays, W. J. Morgan, eds. Knoxville, TN: The Bureau of Educational Research and Service, The University of Tennessee, Woo, Chi-Keung, Ira Horowitz, Stephen Luk and Aaron Lai (2008), "Willingness to pay and nuanced cultural cues: evidence from Hong Kong's incense-plate auction market," Journal of Economic Psychology, 29 35-53. Zetlin, M. (1995), "Feng Shui: smart business or superstition? " Management Review, 84 (8), 2627. 37