Breakthrough in John Marin's graphic art

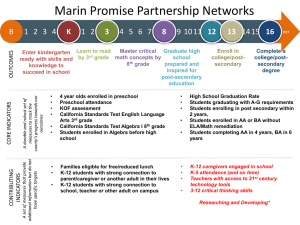

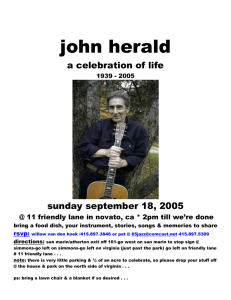

advertisement

(fig. 1) is a key turning point. The purpose of this article is to investigate whether Marin’s background as a practising architect and the influence from modern photography have affected his artistic development; these are areas which have only been sporadically studied hitherto. The reason for Marin’s background as an architect being relatively overlooked can partly be ascribed to his own neglect of this period of his life, and partly to a lack of documentation of his work as an architect. Marin’s artistic production is primarily watercolours and graphics, but he had a past as a practising architect before he became an artist. In 1886, encouraged by his father, he enrolled at a technical university, where he completed half a year’s study. Afterwards, he worked in different drawing offices until he worked as an independent architect between 1892 and 1897. It was not until a couple of years later, in 1899 at the age of 28, that he enrolled at the academy of arts in Philadelphia, where he continued until 1901.2 The meeting between three men – Seligmann, Stieglitz and Marin Brooklyn Bridge and the Urban Landscape – Breakthrough in John Marin’s graphic art by inger krog J ohn Marin (1870-1953) is considered to be a central figure among American modernists, honoured with comprehensive retrospectives at the most renowned American museums and besides singled out as an artist who paved the way for the later Abstract Expressionists.1 In 2004, the Department of Prints and Drawings at Statens Museum for Kunst received ten graphic sheets and seven watercolours by John Marin, thanks to a testamentary gift of Herbert J. Seligmann and his wife Lise Rueff Seligmann. John Marin’s graphic production depicting city architecture will be the crux of this 113 e n g l i s h v e r s i o n article. The graphic works demonstrate the artistic freedom which Marin’s art acquired in the years around 1910, when he returned home from his stay in Europe and settled down in New York. This liberation was abetted by Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946) and his support for modern art. His friendship with Stieglitz is a well-documented chapter in Marin’s artistic career, which this article will present and problematise by way of introduction. Thereafter, Marin’s graphics breakthrough will be exemplified with works from the pictorialistic and atmospheric, to the modernistic and dynamic, where a motif such as Brooklyn Bridge, No. 6 (Swaying) In 2004, Statens Museum for Kunst as mentioned above received as a donation Herbert J. Seligmann’s private art collection of prominent American artists from the beginning of the 20th century. Until this time, American Modernism had not been represented in the collection, but this changed when the museum received works by Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946), Georgia O’Keefe (1887-1986), Marsden Hartley (1877-1943), Arthur G. Dove (1880-1946), among others – and, of course, John Marin. The explanation for it being this particular group of artists Seligmann had collected lay in his personal acquaintance with Alfred Stieglitz and the contact that he acquired through him to these artists, who were shown in Stieglitz’ galleries in New York. The legacy of Seligmann and his wife contained 61 works all told, including paintings, graphics and photography. Over and above these works there was a large quantity of archival material that was donated to the museum, containing, among other things, Seligmann’s private photographs. He was a dedicated amateur photographer, as one can see in the two portraits showing respectively Stieglitz in a white overall (fig. 2) and Marin bowed forward with sunlight on his folded hands (fig. 3). In a corresponding portrait photograph, Stieglitz has captured a comparatively young Seligmann, presumably from the same period as the two preceding photographs (fig. 4). The personal friendship between Seligmann and Stieglitz was initiated by Seligmann’s visit to the gallery 291. Here he was fascinated by the charismatic Stieglitz, and he has later related vividly about Stieglitz’ ability to gather a group of artists and art lovers around him to discuss modern art and its conditions in contemporary America.3 Seligmann himself became a regular guest in the circle around Stieglitz, and at his request he edited Letters of John Marin (New York 1931), which is a collection of Marin’s private correspondence with Stieglitz. In the introduction to the book, Seligmann touches on the relationship between Marin and Stieglitz: ”During the progress of this long sustained laboratory of art and life, which may be said to have come to focus in Marin, he wrote a series of letters to the man, his friend, who made the entire evolution possible.”4 Seligmann hereby emphasises uncritically the decisive importance Stieglitz had for Marin’s artistic development. A mythologised friendship In the years between 1905 and 1910, Marin was in Paris again. According to what he said, and with his typical distance from any attempt to intellectualise himself, he played a lot of billiards with the other American artists who had travelled to the European art mecca.5 In this coterie he was introduced to Edward Steichen (1879-1973), who wrote enthusiastic letters home to New York, telling Stieglitz about Marin’s artistic abilities. Steichen, himself a painter and photographer, had helped Stieglitz open the gallery The Little Galleries of the PhotoSecession at 291, Fifth Avenue in New York in 1905. With the aid of Steichen as gobetween, the first exhibition on American soil of John Marin’s works was arranged here in spring, 1909.6 In the autumn of the same year, Stieglitz went to Paris and met Marin in person, which was to be the start of a lifelong friendship. This meeting and Stieglitz’ later importance for Marin’s artistic development can be followed in Stieglitz’ own memoirs and statements. Seligmann has immortalised these statements in the notes and observations he himself made during his innumerable visits to Stieglitz’ gallery. He wrote down the anecdotal happenings which took place here and industriously quoted Stieglitz; all this was later published in the book with the simple title, Alfred Stieglitz Talking (New Haven 1966).7 Here is the account of Stieglitz’ first meeting with Marin’s art at the gallery in New York in 1909, where Stieglitz remembers that his first impression of Marin’s etchings was James McNeill Whistler’s (1834-1903) influence on them, that is, a retrospective picturesque tradition. Later when he visited Marin in his studio in Paris, he saw quite different etchings from his hand. We do not know what etchings they may have been, but in all likelihood they were etchings in which Marin experimented with freer and more sharply drawn lines with the etching needle than the earlier, more delicately executed ones. In this connection, Marin refers to his art-dealers in the USA, who had advised him against experimenting with new etchings if he hoped to sell his work. Stieglitz’ reaction came immediately: ‘Well, if I were you and could do what you have done, (…) I’d tell the dealer and your father to go to hell.’8 From this point, Stieglitz assumed a father role for Marin.9 As early as in 1910, when Marin returned to the USA again, Stieglitz arranged his first one-man show at 291, and he continued to ensure that Marin had his works exhibited, even in the periods when Stieglitz did not have his own gallery.10 By virtue of his role as gallery owner and debater on art, Stieglitz fought for the recognition of contemporary American artists who were absorbed in developing a modernistic idiom. Seligmann emphasized that all galleries run by Stieglitz had the same purpose: ”Each of these centers was animated by the same motive: to bring about opportunity for the creative artist to work in America.”11 The concept ”creative” in this context must be seen in relation to Stieglitz’ view of art, which was influenced by a direct connection between creativity and freedom. This statement of values involved on the one hand a distancing from the academic tradition, and on the other emphasised the development of a more abstracted idiom; this involved, among other things, that the expressiveness of line became independent of the purely descriptive approach to the motif. How this value statement found its expression can be implicitly read in the story of Marin as the unfree artist, subjugated to commercial demands, who is liberated through the moral support of Stieglitz. There is a sort of myth describing the relationship between the two men, which has been strengthened through repetition, saying that Marin gained a better foundation for developing away from the picturesque and towards the more modernistic idiom, due to Stieglitz’ support.12 However, this story leaves the question unanswered as to whether Marin’s artistic liberation would not have taken place, seen in the light of his ongoing work with his ‘new’ etchings, when Stieglitz visited his studio. As Marin himself remembered this stage of his career: ”Some of the etchings I had been making before Stieglitz showed my work already had some freedom about them. I had already begun to let go some. After he began to show my work I let go more, of course. But, in the water colours I had been making, even before Stieglitz saw my work, I had already begun to let go in complete freedom.”13 This statement underlines the fact that Marin acknowledged Stieglitz’ importance as regards his artistic development, but also that he was already in the process of experimenting with his own mode of expression during his stay in Paris. Marin had clearly been influenced by what was going on around him in the art milieu. Despite him playing down the influence of French PostImpressionism and early Cubism, it is of course an unlikely thesis that he existed in an artistic vacuum.14 For Stieglitz, Marin became the personification of the American artist myth, in which the artist is described as a ”frontiersman” conquering new territory.15 Seligmann describes it like this in a more thoughtful essay: ”For Stieglitz, Marin, as he grew, became more and more a symbol. In himself, Marin was the true, joyous, and simple human being, whom it became a necessity to enable to live, as a flower is cared for, or a tree bearing fruit. He represented, too, all artists, purity of spirit and mastery itself, in America.”16 The mythologizing tale of Stieglitz’ importance for Marin’s breakthrough is therefore twofold. On the one hand, there is no doubt that the financial and moral support that Stieglitz gave Marin over a period of years was an inestimable help to his artistic career. On the e n g l i s h v e r s i o n 114 other hand Marin, as a free American artist, was living proof of Stieglitz’ decisive role as cultural innovator and patron of the arts. This finds clear expression in Seligmann’s record of Stieglitz’ words: ”Here (…) was Marin, who had been able to stay a pure and free spirit. If he, Stieglitz, had not been there, he wondered if that would have been possible.”17 Marin’s artistic liberation became an important point in Stieglitz’ great account of American Modernism, but, as the following presentation of selected graphic works by Marin will demonstrate, there are certain aspects that this account has overlooked. The pictorialistic point of departure Shortly before Marin travelled to Europe in 1905, he purchased a handbook on the technique of etching: Maxime Lalanne, Treatise on Etching (Boston 1880), and made his first experiments in Paris for the first time with an etching needle.18 From the very first year, the main thread of Marin’s work was the city and its architecture; he depicted in picturesque views the less monumental sides of the European cities he visited: an old house with peeling walls, a narrow alleyway or a bridge over a canal. He found the latter in Amsterdam, where he stayed in 1906. In his etching Bridge over Canal, Amsterdam, 1906 (fig. 5), Marin experimented with the artistic properties of the graphic medium. The grey tones of the etching have been produced by not completely wiping off the whole plate after an etched metal plate has been inked – only the light sections. In this way, the print gains the characteristics of a monotype, as the word itself denotes – a single print from a plate which is changed for each inking. Marin achieved a painterly effect from the ink, which not only manifests itself in the etched lines of the plate, but also disseminates itself like a sort of watercolour. The technique blurs the graphic line and gathers the motif in a central composition with the aid of the graduated tone, which darkens towards the edge of the picture. The composition is built up with the half-wall separating the pavement from the canal. The perspective of the half-wall accentuates it as a striking white area reaching inwards and continuing in the darkly accentuated curve of the bridge. The picture is thus divided into two-thirds given over to the tremor of the canal water, and a third to the pavement. Across the 115 e n g l i s h v e r s i o n bridge, a throng of unidentifiable figures can be seen, and the buildings in the background are only hinted at in faintly sketched contours. The motif is unusual for Marin’s early graphic work, in that it does not have the architectural space as its primary focus. Instead the atmosphere outside the architectonic space comes into its own by way of the reflections of light on the surface of the water. The influence of contemporary picturesque photography can have been a decisive factor in his choice of both technique and composition. Pictorialism arose within photography at the end of the 19th century, primarily in England and America as a reaction to the lack of recognition of the photographic medium as artistic expression. The discussion of the mechanical nature of photography contra its aesthetic qualities was at its highest, and photographers experimented with dark room manipulations of a very difficult nature, which were to accentuate the painterly qualities of the medium. The formal effects were compared to those of paintings, and the content should not be inferior to symbolism’s representation of a subjective metaphysical dimension. Edward Steichen was a strong exponent of the movement, who formed the PhotoSecession group with Arthur Stieglitz in 1902, inspired by artistic groups in Europe. With Stieglitz as a driving force, exhibitions were arranged, and the periodical Camera Work came out in the years between 1903 and 1917. Like other American pictorialists, Steichen’s works were inspired by his fellow countryman James McNeill Whistler and his tonal paintings from London, among others. With Whistler, light, colour and atmosphere were the real motif; the so-called nocturnal motifs from the 1870s with their night-time depictions of the Thames and its quiet water are well-known examples of this.19 Whistler’s influence can be traced in both Stieglitz and Steichen in their well-known photographs of the Flatiron skyscraper from 1902 and 1904 respectively, in which one of New York’s monumental landmarks fades into the background or is dematerialised in the evening light.20 Whistler, or maybe more the pictorialists’ interpretation of him, has had an importance which is especially obvious in Bridge over Canal, Amsterdam. The overtly painterly treatment of the motif differs from other etchings by Marin, particularly as regards the centralisation of the motif about the light areas and the atmospheric unity the grey tones create. The dark tone towards the edge of the picture gives the etching a nocturnal atmosphere. It is impossible to say how much Marin knew about pictorialist photography. It is reasonable to suppose, however, that Marin had had an opportunity to follow the publication of Camera Work through his American acquaintances in Paris, like Steichen, for example. In the first numbers of the periodical which was published quarterly, the pictorialist photographs of Steichen, Stieglitz and Alvin Langdon Coburn (1882-1966) were strongly represented. For example, the two photographs of Flatiron were published in this period as well as several motifs by Alvin Langdon Coburn, with bridges fading into the soft atmospheric light.21 One pictorialist photograph which should be called attention to because of its formal similarities with Marin’s etchings is Steichen’s photogravure Moonlight. The Pond from 1904, published in Camera Work in April, 1906 (fig. 6). Here one can see how the light and its reflections in the water become the central motif, gathering the composition in a dark-toned unity. The high horizontal line which leaves two thirds of the picture to the surface of the water is also similar to Marin’s characteristic form of composition, where tree trunks over the pond stand like silhouettes in the same way as Marin’s human figures hurrying across the bridge. A completely different side of Whistler’s influence on Marin’s graphic production is apparent in the more typical etchings by Marin of this period. Whistler made several graphic series of picturesque depictions of cities like London and Venice. His series The Thames Set from 1871 with motifs of life along the banks of the Thames became very popular, just like the series Etchings of Venice from 1880, which shows less wellknown sides of the dilapidated city. The etching Old House, Quai d’Ivry, 1906 (fig. 7), is an example of how Whistler’s influence affected Marin’s choice of motifs, which did not make him any different from other graphic artists of the time.22 The old house with its peeling walls and the boat in the foreground hints at the dilapidated and mundane, without it being spelled out into the banal. Marin’s vibrating line gives the house a special character, like a personification of an old friend. This is emphasised by the chosen point of view as a two-point perspective, accentuating the three-dimensionality of the house. This type of etching, which depicts personified architecture, can be seen as a form of replacement for the very rare portraits Marin made during his career. Instead of focusing on the depiction of the human psyche through studies of the facial features and postures of the persons portrayed, Marin reproduces windows, walls and volume, as can be clearly seen in this case, with a sense for the individuality and aging process of the building. The sensitive depiction of the decay of the architecture points to the nostalgic tones which are also visible in Whistler’s etching. The first expressive steps In 1908, Marin turned to depiction of architecture of a purely commercial nature. As a commission he produced a series of monumental sights in Paris, like the opera and Notre Dame, the Madeleine and Saint Sulpice churches.23 All these etchings were made on plates that were far larger than the small formats Marin was normally used to. Marin’s background as a practising architect must have been a great help in his approach to these more traditional renderings of building bodies, which have the appearance of elevations. As mentioned above, Marin worked as an architect from about 1892 to 1897. This is a period about which Marin has not been particularly forthcoming, but which may nevertheless have contributed to strengthening both his interest in architecture as a motif, as well as his ability to understand and thereby reproduce architectonic construction. As an artistic colleague Marsden Hartley expressed it, ”And it must not be forgotten that he began life as an architectural draughtsman, and that his earlier etchings of the Madeleine and like subjects in Paris show that (…) he (…) knows the meaning of architectural construction, and applies the principle to every wash he lays down.”24 Despite the traditional nature of the motifs as tourist souvenirs, Marin’s are different from other commercial etchings of the time because of his vigorous touch with the etching needle, denoting the movement of clouds above the church towers. The forceful lines are laid down rhythmically and show the first steps towards a freer approach to the medium. Thus one finds the beginnings of the expressive style in Marin’s etchings from 1909, which were later to be fully integrated in his treatment of the whole motif. New York and Brooklyn Bridge Revisited In the years directly after his return to New York, the stylistic breakthrough which had such decisive importance for Marin’s development as a graphic artist occurred. One of the reasons for the full-blown change of style that finally manifested itself can have been the meeting with the American metropolis. After several years in Europe, New York and its skyscrapers which so radically altered the silhouette of the city must have felt like travelling from the retrospective and traditionalist to the progressive and modern. From the old world to the new. Edifices like the Woolworth building from 1911-13 shot up with the ambition of being the tallest building in the world, with its 59 floors and in all 241 meters.25 And Brooklyn Bridge, opened in 1883, became a symbol of the new advances within construction technique, where iron became the crucial factor as a new building material. In 1911 and again in 1913, Marin executed a series of etchings with Brooklyn Bridge as the motif. It is here that the radical development in Marin’s graphic production is synthesised; this was incipient during the last years in Paris. Brooklyn Bridge, No. 6 (Swaying), 1913 (fig. 1). is one example of how Marin accomplishes the rhythmical measure, which can be compared to his written language and its stream-ofconsciousnessness, as can for example be found in his description of how the artist tunes into the frequence of modernity: ”The life of today so keyed up, so seen, so seeming unreal yet so real and the eye with so much to see and the ear to hear. Things happening most weirdly upside down, that it’s all – what is it? But the seeing eye and the hearing ear become attuned. Then comes expression: taut, taut loose and taut electric staccato.” The staccato rhythm of the language can be recognised in the sharply drawn lines leading out of Brooklyn Bridge with its characteristic Gothic pointed arches. The sloping lines are applied in a zigzag pattern along the left side and with the crosses on both sides of the bridge create a dynamism that activates the architecture of the bridge. The crosses denote the pull of the cables under tension, which are an important part of the bearing structure of the bridge. The highly foreshortened perspective seen from the left side of the bridge accentuates the movement of the curved lines disappearing through the pointed arches. The big city’s tempo and speed and the concomitant evanescence in the motif of traffic across the bridge is suggested through the open contour lines, as well as by a figure caught in rapid movement on its way across the bridge. The rendition of the tectonics of the bridge is seen from an architect’s perspective. It is, however, represented in a modernistically abstracted and strongly gesticulating idiom, which has a different fragmentary view of architecture than that of the large traditional pictures of façade elevations from Paris. As earlier mentioned, this can partly be explained by his meeting with the pulsating New York, but another important reason can have been the influence of the photographers whom Marin met after his return to New York. In a letter to Stieglitz dated New York, 11th October 1910, Marin wrote the following: ”As you have no doubt been told by Haviland, the skyscrapers struck a snag, for the present at least; so we had to push in a new direction. Haviland, Steichen and Carles saw the new direction, and may be a step forward. Let us hope so.”26 The Haviland Marin refers to is Paul B. Haviland (1880-1950), of whom he became a close friend. Haviland was a photographer and in April 1914 published two city pictures of New York in Camera Work, with the roofs of the city shown in a slanting bird’s eye view, accentuating the abstract pattern of the diagonal lines which the city streets cut through the mass of the architecture.27 The photographer’s approach to the city as motif prepared the way for Marin, as he describes it himself. This is not to say that it was a direct transfer from photography to Marin’s approach to the graphic medium, but rather a gradual acquisition of a new aesthetic. Haviland, Stieglitz and, last but by no means least, Paul Strand (1890-1976) played a decisive role, in this connection, in the development of modernistic photography characterised by diagonals and fragmented motifs. Strand’s photographs developed e n g l i s h v e r s i o n 116 particularly markedly in these years, with city pictures from New York characterised by a snapshot aesthetic, in which the abrupt cutting-off of passers-by in the city scene indicate the fleeting nature of the motif. The lines and shadows of the architecture are used compositionally to emphasise dynamism in the picture, which is especially apparent in his well-known photographs Wall Street, 1915, and From the Viaduct, 125th Street, New York, 1916.28 An article from 1922 reveals that Marin was deeply involved in the debate as to whether photography was an art form or not, and indicates that due to Stieglitz and his circle, he was of course fully au fait with development in modernistic photography. The article was entitled ”Can a Photograph Have the Significance of Art?”29 With his affirmative answer to this question, Marin refers quite generally to Stieglitz’ photographs. With his well-known photogravure The Steerage (fig. 8), from as early as 1907 and published in Camera Work in October 1911, Stieglitz had helped to develop what he later called ”pure photography”– a view of photography which emphasised unmanipulated ”pure” photography.30 In The Steerage, the formal characteristics are exemplified, which are similarly apparent in the approach of photographers to the city environment. The sharp cutting-off of the motif with the two passenger decks on an Atlantic liner gives the composition of the picture dynamism through two diagonals, which exert a pull in different directions: the funnel to the right and the ladder to the left. The gangway in the centre of the motif emphasises the fragmentariness in the picture and simultaneously gives depth to the composition. The dramatisation of the twodimensional picture plane that the lines create has a certain similarity with Marin’s experiments with the expressive power of line in his graphic works. Just like modernistic photography, Marin does not, however, lose his connection with perceived reality, despite the abstracted idiom. The urban landscape After Marin returned to the USA, New York and its skyscrapers became his preferred motif for etching the rest of his life. Here he found the urban landscape that acted as a response to the natural landscape which he depicted in his watercolours especially from 117 e n g l i s h v e r s i o n Maine. Watercolours were an important part of Marin’s production, in which he explored the expressive character of colour; this can be seen in Valley Landscape, 1918 (fig. 9), and Sailboat, 1923 (fig. 10). In contrast to the watercolours which Marin worked with whatever the locality, graphics of this period were exclusively employed to depict architecture.31 Whatever the motive, one can note today that there is a connection between the visual expression of the New York skyline and Marin’s use of etchings. The black/white medium was apparently more suited to depicting the silhouette of the city than the representation of the glowing colours of nature. The urban landscape is seen in the etching Lower Manhattan from the Bridge, 1913 (fig. 11), which is a typical example of Marin’s view of New York and its architecture. Then, two decades after his return from Europe, Marin depicted how the city had been affected by the leap in scale which architectonic development had occasioned. From the traditional low building along the Hudson River to rise sharply to the skyscrapers further in on Manhattan. The view from the bridge gives a slanting bird’s eye view of the cityscape, with its topography created by the infrastructure and tightpacked housing. From this distance, Marin’s typical depiction of the human swarm at street level disappears. As a sort of compensation for this life in human scale, the buildings in the foreground are animated. The closely-packed masses are emphasised through the frames which are reduplicated several times, but are unfinished. The skyscrapers rise against a neutralised background, drawn with a contrastingly slight contour line. The abrupt cutting-off of the motif both in the foreground and background gives a centralised composition, which helps to unify the motif. Marin did not only express his reading of the topography of the city in purely visual terms, but also described it in a short text for a one-man show at 291 in 1913: ”I see great forces at work; great movements; the large buildings and the small buildings; the warring of the great and the small; influences of one mass on another greater or smaller mass. Feelings are aroused which give me the desire to express the reaction of these ’pull forces’, those influences which play with one another; great masses pulling smaller masses, each subject in some degree to the other’s power. […] While these powers are at work pushing, pulling, sideways, downwards, upwards, I can hear the sound of their strife and there is great music being played. And so I try to express graphically what a great city is doing. Within the frames there must be a balance, a controlling of these warring, pushing, pulling forces. This is what I am trying to realize.”32 One can visualise the contrasts and tensions between volumes which he describes, in Lower Manhattan from the Bridge. The compositional construction of impact and warring forces can be an abstract visualisation of the music Marin seems to have heard on meeting the new architecture. The forces of this architecture push and drag to one side, up and down, and are translated into the violent movements made by Marin’s etching needle as it scratches contour lines. It is as if Marin’s physical movements express the dynamism he sees at play between the buildings’ masses. He mentions his views on architecture in the same quotation as above: ”Shall we consider the life of a great city as confined simply to the people and animals on its streets and in its buildings? Are the buildings themselves dead? We have been told somewhere that a work of art is a thing alive. You cannot create a work of art unless the things you behold respond to something within you. Therefore if these buildings move me they too must have life.”33 The affinity between John Marin’s use of his etching needle and his perception of animated architecture shows his strength as a modern graphic artist. He exploits the expressive potential of the medium to the utmost to depict the pulsating city life, which is most powerfully expressed in his chief work Brooklyn Bridge, No. 6 (Swaying). The work marks a liberation in Marin’s artistic production, which was both helped along by Stieglitz and 291, and also the formalistic experiments which were simultaneously taking place in photography. Marin’s graphic production from the softly toned etchings to the sharply drawn staccato rhythms in his urban landscapes can thus be seen in continuation of the development from pictorialistic atmospheric photography to contrast-filled modernistic photography. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 In 1936 Marin was honoured as the first American artist to be granted a retrospective exhibition at MoMa; see E. M. Benson et al., John Marin: Watercolors, Oil Paintings, Etchings, Museum of Modern Art, New York 1936. In 1950 he was well represented in the American pavilion at the 25th Venice Biennale together with Jackson Pollock, among others. After Marin’s death in 1853, several memorial exhibitions were arranged, for example in New York at the American Academy of Arts and Letters, see Thornton Wilder, John Marin: 1870-1953, American Academy of Arts and Letters, 1954. The critic Robert Rosenblum called attention to Marin in the same year as a forerunner of Abstract Expressionism: ”He [Marin] stands in full center of the major currents of American art … he parallels, even prophesies, abstract-expressionist trends … The formal analogies with, say de Kooning or Tomlin, are striking, and one is again pressed to pay homage to this master …”, see Robert Rosenblum, ‘Marin’s Dynamism’, Art Digest no. 28, 1954, p. 13. In 1969 a descriptive catalogue of Marin’s graphic art was published, followed by a comprehensive exhibition; see Carl Zigrosser, The Complete Etchings of John Marin, Philadelphia Museum of Art 1969. In the following decades, interest in John Marin was more muted, but finally in 1990, the National Gallery of Art in Washington arranged a large monographic exhibition of both graphic art, watercolours and paintings, occasioned by the donation by Marin’s son and daughter-in-law of more than 400 drawings and watercolours, see Ruth E. Fine, John Marin, National Gallery of Art, Washington 1990. The headline of a review of the exhibition John Marin: The 291 Years in Richard York Gallery, New York in 1998 indicates that Marin had been a comparatively forgotten artist for a period: Hilton Kramer, Reintroducing John Marin, Forgotten Modern Master, The New York Observer, December 14, 1998, p. 36. See Ruth E. Fine, John Marin, National Gallery of Art, Washington 1990, pp. 23-25 and 289 See Herbert J. Seligmann, ‘291: A Vision through Photography’ in America and Alfred Stieglitz, New York 1934, pp. 105-125. Herbert J. Seligmann (ed.) Letters of John Marin, New York, 1931, introduction unpaginated. Dorothy Norman (ed.), The Selected Writings of John Marin, New York 1949, introduction p. x. The exhibition introduced both Marin and Alfred Maurer (1868-1932), but Stieglitz’ allocation of hanging space is an early indication of his personal preference. Instead of dividing the space equally between the two artists, he chose to hang Marin’s watercolours on three walls, allowing Maurer the third only. See the exhibition catalogue: Watercolors by John Marin and Sketches in Oil by Alfred Maurer, 291, New York, March 30 – April 17, with 25 watercolours by Marin and 15 paintings by Maurer. See also Barbara Rose, John Marin, The 291 Years, New York 1998, p. 15. Herbert J. Seligmann, Alfred Stieglitz Talking, New Haven 1966. The book was published by Yale University Library, to which Seligmann had donated his private correspondence with Stieglitz in 1953, and where The Alfred Stieglitz Archive was established after a large donation by Georgia O’Keefe in 1949. Ibid. p. 1. When Marin wanted to establish himself as an artist, he was met with both scepticism and worry from his 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 father, which was probably also one of the decisive factors in the comparative lateness of Marin’s breakthrough as an artist. Their relationship was, however, not so strained that his father did not support him financially in all the years in Europe. After his return to the USA, Stieglitz, according to himself, fought stoutly for Marin’s artistic integrity. When his father suggested that Marin could do commercial etchings in the morning and wild watercolours in the afternoon, Stieglitz answered that the father could just as well ask newly-wed Mrs. Marin to be a prostitute in the morning and a virgin in the afternoon; see Ruth E. Fine, John Marin, National Gallery of Art, Washington 1990, p. 46. In 1917, 291 closed, but from 1925 to 1929, Stieglitz ran The Intimate Gallery, where he continued to arrange an annual one-man show for Marin. From 1930 until his death in 1946, Stieglitz continued to arrange yearly one-man shows with Marin at his last gallery An American Place. Herbert J. Seligmann (ed.) Letters of John Marin, New York 1931, introduction unpaginated. John Marin’s first biographer E. M. Benson emphasises as early as 1935 the decisive importance Stieglitz had for Marin’s artistic breakthrough, see E. M. Benson, John Marin, The Man and His Work, Washington 1935, p. 28. Quoted in Dorothy Normann (ed.), The Selected Writings of John Marin, New York 1949, p. xi. See e.g. E. M. Benson, John Marin, The Man and His Work, Washington 1935, pp. 16 and 31, as well as a discussion of Marin’s alleged seclusion from contemporary art in Ruth E. Fine, John Marin, National Gallery of Art, Washington 1990, pp. 77-79. According to Marin’s own view, as it finds expression in letters to Stieglitz, he was a family man, who loved shooting, fishing and nature, besides being an artist. He describes himself as a ”worker” and was called ”John Marin, Frontiersman”, which is the title of an article by Frederick Wright in the catalogue of the John Marin Memorial Exhibition, Los Angeles: Art Galleries, University of California, 1955. See also Barbara Rose, John Marin: The 291 Years, Richard York Gallery, New York 1998, pp. 26-27. Herbert J. Seligmann, ‘291: A Vision through Photography’ in America and Alfred Stieglitz, New York 1934, p. 115. Herbert J. Seligmann, Alfred Stieglitz Talking, New Haven 1966, p. 88. There were several practical circumstances surrounding his arrival in Paris, which helped Marin get started with the graphic medium. His stepbrother, Charles Bittinger (1879-1970), who was also an artist, had been living in Paris for a number of years at the time when Marin arrived there. He had experience with the graphic arts and helped Marin with the technical preparations by installing a printing press for him. Furthermore, Bittinger lived in the same house as the American graphic artist George C. Aid (1872-1938), to whom he introduced Marin. See e.g. Nocturne: Blue and Silver – Chelsea, 1871, Tate Britain, London. Published in Camera Work with Alfred Stieglitz, ‘The Flat-iron’ in October 1903 and Edward J. Steichen, The Flatiron – Evening in April 1906 respectively. Reproduced in Marianne Fulton Margolis, ‘Camera Work’. A Pictorial Guide, New York 1978, pp. 11 and 39. See Marianne Fulton Margolis, ‘Camera Work’. A Pictorial Guide, New York 1978, pp 14, 46. 22 Carl Zigrosser, The Complete Etchings of John Marin, Philadelphia Museum of Art 1969, p. 11:”It must be kept in mind that Whistler’s prestige in graphic art was at its peak in the decade in 1903. No young etcher could escape his pervasive authority. Marin did not copy slavishly to produce little Whistlers: he was merely speaking in the common idiom of the day.” 23 Ibid. pp. 12-13 and no. 79-82. 24 Marsden Hartley, in the exhibition brochure from Marin’s one-man show: Marin Exhibition, The Intimate Gallery, November-December, 1928, unpaginated. 25 Marin executed also a series of motifs of the Woolworth building in 1913, see Carl Zigrosser, The Complete Etchings of John Marin, Philadelphia Museum of Art 1969, nos. 113-116. 26 Dorothy Normann (ed.), The Selected Writings of John Marin, New York 1949, p.3. 27 Reproduced in Marianne Fulton Margolis, ‘Camera Work’. A Pictorial Guide, New York 1978, p. 131. 28 Ibid. pp. 134 and 139. 29 Ibid. pp. 86-88. 30 See Sarah Greenough and Juan Hamilton, Alfred Stieglitz. Photographs and Writings, National Gallery of Art. Washington 1983, p. 20, for a discussion of de Zayas’ definition of ”pre photography” and Stieglitz’ influence on de Zayas. 31 This holds true for the period right up to 1932, when Marin executed the first etchings with a different motif than architecture, namely a sailboat. 32 Written for the exhibition at 291 in 1913 and published in Camera Work nos. 42-43, April-July 1913. Quoted from Dorothy Normann (ed.), The Selected Writings of John Marin, New York 1949, pp. 4-5. 33 Ibid. p. 4. e n g l i s h v e r s i o n 118