Administrative Law Outline

Administrative Law Outline

Introduction

Administrative law is the branch of law which deals with the administration of governmental agencies.

Governmental agencies are created to effect the interests of the particular government which created it. Be that the

Federal government. Or a State government or an arm thereof.

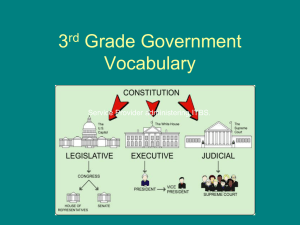

An agency is in essence a micro version of the Federal government. It has a legislative function to create rules and regulations. It has an executive function to carry out the affairs and purposes for which it was created. And it has a judicial function to adjudicate disputes between the agency and those to whom the rules and regulations are applicable. These agency functions are referred to as being quasi-legislative, quasi-executive, and quasi-judicial.

However an agency is not a government unto itself. Besides being limited by the statutory language which created it, agencies are subject to and must conform themselves to the Constitution of the United States. As such, administrative law is rift with Constitutional issues, as are other branches of law which impose duties upon, grant benefits to, and protect the freedoms of the people.

README.TXT

1) As applied to administrative law attach little significance to words like hearing, trial, decisionmaker, judge, justices, et al, in reading your cases, outlines, legal treaties, et al. Theses words are thrown around in the literature like interchangeable frisbees. And if you attach any sigificance to them in a 'per se' kind of way in your mind, you will wind up all balled up. (There are some better ways to accurately express all balled up. But they are known as

"bad words".)

So What To Do?

1. Ad judication refers to something going on or gone on by an Ad mininstrative agency.

Judicial, judication, judiciary refers to something going on, gone on, by the same ol' Federal and State court systems we have previously learned about in

Torts, Contracts, CrimLaw, etc.

2) Look to see what is the End Result which is trying to be achieved. Then look to see who is doing it. Start there.

Then you'll know where you are, what the process is that is going on. Then you'll know who is doing it. Then you'll know which rules you should be applying.

3) The processes in Administrative law are: i) The process of deciding whether to make a rule and what that rule should be. ii) The process of the agency Decisionmaker saying, "Yup, we're gonna promulgate this rule." iii) The process of a rule being applied to a party where it is the agency Decisionmaker who decides the outcome. iv) The process of an Adjudication where an agency's own Administrative Law Judge decides the outcome. v) The process where the Decisionmaker overrules the Administrative Judge's decision. (yup...kinda makes ya think, "so what's the point?") vi) The process where a regular 'ol Federal or State court judge decides the outcome, ie, makes a Judicial decision in a Judiciary proceeding. (end of game, so to speak, for the agency. Judges rule!) From there it can go up that whole regular court system chain of trial, appeal, and so on, that we learned about in CivilPro, Criminal Procedure and ConLaw.

4) A "Due Process" right can apply to the right to an agency Adjudication and the right to a Federal/State Judiciary process. Just because a party has a right to due process does not mean the party has a right to immediately hop right over to a state or Federal court. Just because a due process right is being decided upon does not automatically mean the proceeding is a judicial one. It could be an agency adjudication. Look closely at the facts to determine where you are. Who is doing it? Then apply the appropriate rules.

5) The terms 'informal', 'hybrid', and 'formal' only refer to administrative law agency processes. You ever learned

about an informal trial in Torts or CrimLaw? Don't apply these terms, nor their rules, to regular Federal and State judicial court systems. Only agency stuff. Same with the ex parte communications rules in the administrative law

'informal', 'hybrid', and 'formal' agency processess. Only apply them in the agency related specific processes.

6) Keep the agency adjudicative system separate in your mind from the Federal and state judicative court system.

For example: The adjudicative rules of evidence stay in the adjudicative process. When a case decided on in the adjudicative process, using the adjudicative rules of evidence, is brought into the Federal and state court system those admin rules of evidence do not hop over with the case just because it originated as an agency administrative law case. The rules we learned in Evidence, the Federal and California rules of evidence, apply in judicial cases, regardless that it started out as an admin agency case.

Now we can charge along smartly into Admin Law.

The outline is organized in the same order as the processes listed above after an initial treatment of the ConLaw issues :

1) ConLaw issues

2) Rulemaking and Application of the Rules by the agency Decisionmaker (processes i, ii, and iii, above)

3) Adjudicatory processes, iv and v

4) Judicial Review, process vi.

GOVERNMENTAL CONTROL OF AGENCY ACTION

Delegation of Governmental Power

Non-delegation Doctrine

All legislative power is vested in the Congress of the United States. (Article I of the Constitution)

Congress itself must make all critical policy decisions. (Industrial Union Dept, AFL/CIO v American Petroleum,

1980 The Benzene Case)

A delegation of legislative authority is constrained by the separation of powers doctrine and the language of the statutory mandate. (Boreali v Axelrod, 1987)

Intelligible Principle

A delegation of legislative power does not violate the non-delegation doctrine if there is an intelligible principle to which the agency must conform itself. (Amalgamated Meat Cutters and Butcher Workmen v Connally, 1971)

Intelligible standards or guidelines must accompany legislative delegations of power. To be valid, a legislative delegation should include the persons and activities subject to regulation, the harm sought to be prevented, and the general means available to the administrator to prevent the harm. (Thygesen v Callahan, 1979)

Separation of Powers

Historical Note:

The term "separation of powers" is not found in the Constitution. It came from the writing of a Frenchman, Baron

De Montesquieu. The Englishman, John Locke, proposed in his own writing that a government should have two separate branches, the executive and legislative. Taking Locke's theory, Baron De Montesquieu expanded it to include a judicial branch. And in his writing, the Baron coined the term, "separation of powers". The Baron's concept is shown by application in our Constitution when our Founding Fathers separated the powers of each of the 3 branches with their own separate Article: Article I denotes the powers of Congress, Article II denotes the

Executive powers, and Article III the powers of the Judiciary. Thus implying and effectuating the "separation of powers" without actually using that term within the Constitution.

Officers of the United States who are appointed by the President with the advice and consent of the Senate, and are subject to congressional removal only by impeachment, may engage in the enforcement of federal law without violating separation of powers. (Federal Trade Commission v National Cellular, Inc., 1987)

Examples of Permissive Delegation of Legislative Power to Agencies within the Executive and Judicial Branches

Congress may delegate limited jurisdiction in non-Article III courts over a narrow class of common law claims when the delegation does not create a substantial threat to the separation of powers. (Commodity Futures Trading

Commission v Schor, 1986)

Congress may delegate to a judicial branch agency nonadjudicatory, quasi-legislative, functions that are appropriate to facilitating the central mission of the judiciary, which is to preside over cases and controversies under Article II of the Constitution, without violating the separation of powers. (Mistretta v United States, 1989)

The exercise of rulemaking by an agency within the judicial branch does not violate the separation of powers if the exercise of rulemaking has been delegated by Congress. (Mistretta v United States, 1989)

A state agency located in the executive branch is not an 'inferior court' within the meaning of Article III of

Constitution. If it were, this would be a violation of the separation of powers. Therefore it's decisions are not directly reviewable by the state supreme court by certification. (Mulhearn v Federal Shipbuilding & Dry Dock

Co., 1949)

Impermissive Legislative Delegation

Congress may not delegate unto itself, or to legislative appointees, the powers reserved to the Judicial and

Executive branches.

Examples of Impermissive Legislative Delegation

The Legislative Veto By circumventing Article I's requirement that all legislation must pass through both houses of Congress and receive the president's signature in order to become law, a legislative veto without presentment denies the president his constitutional right to participate in the lawmaking process, and thus violates the separation of powers doctrine. (Immigration and Naturalization Servie v Chadha, 1983)

Congress, by deciding the merits of an individual case, has assumed a judicial function in violation of the separation of powers doctrine. (Immigration and Naturalization Service v Chadha, 1983)

It is a violation of the separation of powers doctrine for Congress to grant executive powers to a legislative official.

By placing executive responsibility in the hands of an officer who is subject to removal only by the legislature,

Congress has retained control over the execution of legislation, unconstitutionally intruding into the executive function. (Bowsher v Synar, 1986)

Delegation of Legislative Powers

When delegating legislative authority, Congress must also provide the limits to that authority. (A.L.A. Schechter

Poultry Corp. v United States, 1935)

Congress may delegate to an agency the power to administer a law. Under such a delegated power, an agency has the power to make such rules as necessary to administer a law, but have no power to say what the law shall be.

(State ex rel. Railroad & Warehouse Comm. v Chigago, M & St P Ry., 1988)

Congress may not exercise its fundamental power to formulate national policy by delegating that power to one of its two houses, to a legislative committee, or to an individual agent of the Congress. (Bowsher v Synar, 1986)

The constitutionality of a legislative delegation rests upon the scope of the power granted and the specificity of the standards governing its exercise. (Synar v United States, 1986)

A standard of in the "public interest" is sufficiently definite to guide an agency's investigations and decisions.

(Reid v Engen, 1985)

Delegation of Adjudicative Powers

Congress may vest traditional judicial decisionmaking authority in administrative agencies. (Thomas v Union

Carbide Agricultural Products Co, 1985)

An agency may not create criminal codes. Where Congress has made the violation of a properly enacted agency regulation unlawful, criminal penalties may be imposed for such a volation. The power to penalize belongs to

Congress, not the agency. (United States v Grimaud, 1911)

Congress may establish administrative tribunals to decide disputes between the government and private parties.

(Crowell v Benson, 1932)

When Congress has created a statutory cause of action closely integrated into a public regulatory scheme, the adjudication of such "public rights" may be delegated to non-Article III tribunals, and the 7th Amendment guarantee of a jury trial would not apply. A non-Article III tribunal may adjudicate cases involving "public rights" only if the federal government is a party to the proceeding. (Granfinancieroa S,A. v Nordberg, 1989)

Congress may grant an agency the power to make factual determinations in disputes between private partites.

(Crowell v Benson, 1932)

The state legislature may grant an agency the power to impose discretionary civil penalties, including monetary ones, where this power is necessary to accomplish the agency's goals. (Waukegan v Pollution Control Board,

1974)

Since only officers of the United States who have been appointed as per the Appointments Clause have the power to execute law, Congress cannot enact a law that vests in itself the power to to appoint those who will execute and administer a statute, nor may congressional appointees administer or enforce the law. (Buckley v Valeo, 1975)

Other Legislative Controls over Administrative Action

A statute need not expressly state the standards limiting an agency's delegated powers, but the procedure established must furnish adequate safeguards to those affected by the state administrative action. (Warren v

Marion County, 1960)

The legislature must provide strict standards to prevent an abuse of the delegated power when delegating power to an administrative board made up of interested members of an industry. (Allen v California Board of Berber

Examiners, 1972)

A legislative effort to balance the composition of an appointed board by selecting partisan members does not inherently violate adjudicatory impartiality. But the appointment of an adjudicator who has a distinct financial or personal stake in the outcome would be a constitutionally prohibited violation of impartiality. (United Farm

Workers v Agricultural Employment Relations Board, 1984)

Executive Controls over Administrative Action

Appointment Powers

Under the Appointments Clause of the Constitution the power to appoint 'inferior officers' is vested solely in the

President, the Courts of Law, and the Heads of Departments. (Freytag v Comissioner of Internal Revenue, 1991)

Since Article II of the Constitution vests general executive power in the president alone, the decision to remove an important executive official must lie completely within the presidents discretion to insure the uniform execution of the laws contemplated by the Constitution. (Myers v United States, 1926)

The President's ability to appoint and remove federal judges to an agency within the judicial branch does not threaten judicial independence because such power cannot diminish the judges' central Article III authority.

(Mistretta v United States, 1989)

Removal Powers

Congress may restrict the president's power to remove government officials except where the removal restrictions impede the president's ability to perform his constitutional duty. (Morrison v Olson, 1988)

Limitations on Executive Control of Agencies

The executive branch has no authority to use its regulatory review to delay promulgation of administrative regulations beyond the date of a statutory deadline. (Environmental Defense Fund v Thomas, 1986)

Independent Agencies

As with other agencies the President holds the power to appoint the members, with consent by the Senate, of the

Board or Commission which oversees the activities and functions of the agency. However, normally there are statutory provisions limiting the President's authority to remove commissioners, typically for incapacity, neglect of duty, malfeasance, or other good cause. If the agency has enforcement powers, Congress may not remove agency officials. Typically the Board or Commission members serve for a fixed term, by a staggered plan of replacement.

Congress may restrict the president's removal power over officials who occupy no place in the executive department and exercise no part of the executive power vested by the Constitution, that is, those acting in a quasilegislative or quasi-judicial capacity, as opposed to purely executive officers. (Humphrey's Executor v United

States, 1935)

If authorized by Congress the President may appoint and remove judges within an independent agency located within the judicial branch without violating the separation of powers. (Mistretta v United States, 1989)

Where an agency's function is wholly adjudicative, the president has no power to remove it's administrative officials, even if the enabling statute does not explicitly limit the president's discretion. (Weiner v United States,

1958)

Judicial Control over Agencies

Ultra Vires Review

Judicial control over an agency is limited to an ultra vires review. The purpose of ultra vires review is to determine if the particular agency is acting within the bounds of its jurisdiction as defined by its enabling statute and, generally, to curb the expansion of administrative powers into unauthorized areas. 'It's jurisdiction' refers to both the types and amount of authority an agency has been delegated, and also the subject matter the agency is authorized to oversee.

Subsequent Control of Delegated Power

A court will narrowly construe all delegated powers that curtail or dilute activities that are natural and often necessary to the well-being of an American citizen. (Kent v Dulles, 1958)

Administrative adjudications must be subject to de novo judicial review by the courts because the courts possess complete authority to insure the proper application of the law. (Crowell v Benson, 1932)

Sources of Administrative Law

Rules and Orders

Rules and Regulations are made through an agency's quasi-legislative powers. Their purpose is to set out and bring into effect the policies of the agency, as per the agency's enabling statute. Orders are issued through an agency's quasi-judicial power. Their purpose is to enforce the agency's policies.

Traditionally, rulemaking was the means an agency used of promulgating it's generally applicable policies, and rules were considered to be prospective in effect. Orders issued by the adjudication process were the enforcement of those policies as applied to a particular individual, or a particular segment of the public to whom the rules were generally applicable. Orders were considered to be retroactive in effect.

Just as in the resolution of disputes within the court system results in new laws, ie, case made law, so too in an agency's adjudicative process, as a result of resolving disputes between individuals and the agency, can new rules come into being and be given effect. These new rules themselves may, in effect, promulgate, change, or amend agency policies.

A rule is any agency statement about how it proposes to administer a statutory provision. (State Board of

Equalization v Sierra Pacific Power Co, 1981)

A rule is an agency internal policy, which is a fixed, general policy applied without regard to the facts or circumstances of a given case. (Cordero v Corbisiero, 1992)

Federal Agency Supremacy

A state agency is subject to the rules and regulations promulgated by a Federal agency when it is operating under a proper delegation of such rulemaking power by Congress. (In re Permanent Surface Mining Regulation

Litigation, 1981)

Policy Formation

Agency Discretion

T he delegation of legislative power may properly involve the exercise of judgment by the agency on matters of policy. Such a delegation of discretionary power is constitutional provided sufficient standards are present to guide the agency's actions in accordance with the underlying congressional intent. (Mistretta v United States,

1989)

Congress is permitted to transfer essential legislative functions when accompanied by defining standards to prevent unhindered discretion. (Panama Refining Co v Ryan, 1935)

Rulemaking versus Adjudication

An agency's order in an adjudicatory hearing must be based upon the relevant and proper standards, regardless of whether those standards had been previously articulated in a general rule or regulation. (SEC v Chenery Corp. I,

1947)

An agency may use its discretion to determine whether to proceed by rulemaking or adjudication. Agencies alone can determine the best method for enforcement of regulations; courts may not preclude agencies from using caseby-case adjudication rather than rulemaking. (SEC v Chenery Corp. II, 1947)

Unless expressly provided by statute, an adjudicatory hearing is not required during rulemaking procedures.

(Anaconda Co v Ruckelshaus, 1973)

If a new agency standard or principle is being applied for the first time by an adjudicative proceeding it will not be overturned unless the agency abused its discretion or rulemaking is expressly required by statute. (National Labor

Review Board v Bell Aerospace Co, Division of Textron, Inc, 1974)

When the legislature explicitly provides an agency with rulemaking powers, the agency should clarify vague legislative commands through rulemaking rather than ad hoc adjuciation. (Megdal v Oregon State Board of Dental

Examiners, 1980)

An agency may not replace the statutory rulemaking provisions with a procedure of its own invention. Adjudicated cases may announce agency policies and serve as precedents, but need not be obeyed as generally applicable rules without further legal actions. (National Labor Relations Board v Wyman-Gordon Co, 1969)

An agency may promulgate prospective rules through adjudication, as well as rulemaking. To require otherwise would force the agency to determine the temporal effect of its holding prior to the adjudication/rulemaking decision. (National Labor Relations Board v Wyman-Gordon Co, 1969)

An agency may not make ad hoc decisions, distinguishing among applicants, based upon a rule that has not been promulgated in accordance with the formal rulemaking procedures of the Administrative Procedure Act. (Morton v

Ruiz, 1974)

An order in an adjudicatory hearing must be based upon the relevant and proper standards, regardless of whether

those standards previously had been articulated in a gerneral rule or regulation. (SEC v Chenery Corp. I, 1947)

An agency must choose to develop a set of standards, either through rulemaking or adjudication, with which to decide cases. However, if the agency decides to proceed through adjudication, the decisionmaker must clearly articulate the reasons behind each determination in a manner susceptible to judicial review. (Allison v Block,

1983)

When an agency interprets a statute as an incident of its adjudicatory function, it may apply a new interpretation of the statute in the preceding before it. A reviewing court should consider the following factors in determining whether such "retroactive" application of the new rule should be permitted include: 1) whether the case before the agency was one of first impression, 2) whether the new rule represents an abrupt departure from well established practice, 3) the extent to which the party against whom the new rule is being applied relied on the former rule, 4) the burden which a retroactive order imposes on a party, and 5) the statutory interest in applying a new rule despite the parties' reliance on the old standard. (Clark-Cowlitz Joint Operating Agency v Federal Energy Regulatory

Commission, 1987)

Legislative versus Adjudicative Facts

"Legislative" facts primarily involve determinations of broad policies or principles of general application, e.g., whether every tract of land in a large city has been under-assessed for property tax purposes. "Adjudicative" facts pertain to a particular person or small group of persons, e.g. where the tract of land owned by a particular person or tracts by a small group of persons, has been under-assessed for property tax purposes.

Prospective versus Retroactive Effect

An agency's pronouncement in an adjudication can have both a prospective and retroactive effect. Although an agency may possess rulemaking powers, it may often be forced to formulate new standards of conduct through adjudication. (SEC v Chenery Corp. I, 1947)

Limits on Agency Discretion

Duty to Explain Policy Departures

While agencies may change previously announced policies, ignore its prior holdings, and fashion exceptions and qualifications, they must explain departures from agency policies or rules apparently dispositive of a case.

(Brennan v Gilles & Cotting, Inc, 1974)

Retroactive Rule Promulgation

An agency may not promulgate retroactive rules even if substantial justification is present unless that power is expressly conveyed by Congress. (Bowen v Georgetown University Hospital, 1988)

Sources of Rulemaking Procedures

The sources of rulemaking procedures are Federal and state Administrative Procedure Acts, legislative, public participation, and judicially through case made law.

Rulemaking Procedures

Agencies are free to devise their own rulemaking procedures as long as agency procedures are constitutionally and statutorily sufficient, and extremely compelling circumstances do not exist. (Vermont Yankee Nuclear Power corp

v Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc, 1978)

In the interests of efficiency, a statute may permit an agency to limit the cross-examination, oral testimony, and other hearing rights, of interested parties. (Harry and Bryant Co v Federal Trade Commission, 1984)

All documents used in a rulemaking procedure must be disclosed, even those received under a pledge of confidentiality. Failure to disclose invalidates the rulemaking process. (Wirtz v Baldor Electric Co, 1964)

Informal Rulemaking

Informal rulemaking procedure requires notice and an opportunity to comment on a proposed rule, publication of

the final rule, a ban on most ex parte communication, as discussed below. The is no requirement for an informal hearing when the subject matter of a proposed rule is related to military or foreign affairs, internal agency matters and personnel, and propriety matters (public property, loans, grants, benefits and contracts.)

"Arbitrary and Capricious"

In the absense of a written record, a court must presume that a state of facts exists to justify the agency action, unless the opposing party can prove the agency action was arbitrary and capricious. (Pacific States Box & Basket

Co v White, 1935)

The use of undisclosed relevant data prevents interested parties from making comments, the agency decision was then not based on all relevant factors, and must be set aside as 'arbitrary or capricious'. (National Black Media

Coalition v Federal Communications Commission, 1986)

A rule which results from a forecast of possible future events, when based upon an agency's expertise, is not arbitrary and capricious. (Federal Communications Commission v National Citizens Committee for Broadcasting,

1978)

Disclosure

An agency must disclose data used in informal rulemaking when it's omission would impede the presentation of relevant comment and prevent compilation of an adequate record of the proceedings. (United States v Nova Scotia

Fodd Products Corp, 1977)

Hybrid Rulemaking Proceedings

A hybrid proceedings is in most ways the same as an informal hearing with two exceptions: a hybrid hearing, called a "Paper Hearing", will produce a written record sufficient for judicial review of the proceeding, and some ex parte communications are permissible in a limited form, as discussed below.

Formal Rulemaking

As with informal and hybrid hearings a formal hearing requires notice, an unbiased decisionmaker, and publication of the final rule. It's distinguishing characteristics are, 1) a formal hearing is required if the enabling statute requires a decision to be "on the record after an opportunity to be heard", (but the mere mention of a 'hearing' is not sufficient to trigger the formal hearing requirement), 2) a full written transcript of the proceedings, 3) oral proceedings with opportunities for interested parties to submit evidence and cross-examine witnesses, unless the agency or ALJ decides parties will not be prejudiced by limiting the proceedings to written submissions only, and

4) a strict ban on ex parte communications.

Formal rulemaking proceedings must be held if an agency action would have the effect of a decision requiring a formal rulemaking hearing. (Moss v Civil Aeornautic Board, 1970)

Formal rulemaking proceedings are required where expressly mandated by statute, and is quasi-adjudicatory, rather than quasi-legislative, in nature. (American Airlines v Civil Aeronautics Board, 1966)

Procedural Differences in Rulemaking

Notice and comment

Federal Register

1) A rule which must be published and is not has no force of law. Even if the party affected by the rule had actual notice of the rule. No publication, no power to enforce.

2) Publication of a rule gives the populace constructive notice of the rule.

3) Publication of a rule is insufficient notice when a party's liberty or property rights are at stake. The party is due actual notice.

4) Agencies which must maintain secrecy in the interests of national security are exempt from the publication requirement.

A new opportunity to comment upon a proposed rule must be afforded whenever significant information is added

to or altered in the agency's final published explanation of an adopted rule, unless it is a logical outgrowth of the preceding notice and comment proceedings. (Weyhauser Co v Costle, 1978)

Sufficient Notice

A notice is sufficient if it describes the issues with clarity and specificity, such that interested parties may participate in a meaningful and informed manner. That the final rule is different in form and substance form the original proposal does not in and of itself demonstrate interested parties were not adequately informed of the issues under consideration. (American Medical Association v United States, 1989)

Exemptions

Notice and comment procedures exemptions: 1) when issuing interpretive rules to explain ambiguous terms in legislative enactments, 2) when issuing general policy statements to announce their tentative intentions for the future without binding themselves, 3) when issuing rules of agency organization, procedure or practice, to organize their internal operations. (American Hospital Association v Bowen, 1987)

Rules of "agency organization, procedure or practice"

It does not turn on what label an agency chooses to give a rule, if a rule substantially alters the rights of regulated parties, it must be proceeded by notice and comment. (Air Transport Assn of America v Department of

Transportation, 1990)

Benefits to Recipients

An agency rule which provides benefits to recipients is exempt from the APA's requirement of notice and comment. (Humana of South Carolina v Califano, 1978)

Procedural Rules

A rule which is primarily procedural will not be exempt from providing notice and comment as allowed under the

APA if it departs from existing practices of the agency and will have a substantial impact upon the rights of those affected by the rule. (United States Dept of Labor v Kast Metals Corp, 1984)

Policy Statements

A general policy statement is one that does not impose any rights or obligations, may not have a present effect, and must leave the agency and its decisionmakers free to exercise discretion. (Community Nutrition Institute v Young,

1987)

A general statement of policy is exempt from the notice and comment requirement of an informal rulemaking. A statement of policy is one which is prospectively only and must not be binding or determinative but leaves the agency official free to consider the individual facts of the various cases that arise. (Mada-Luna v Fitzpatrick,

1987)

Interpretive rules

A rule that the agency intends to be no more than an expression of its construction of a statute or rule is interpretive, and exempt from the notice and comment requirements of informal rulemaking. (Chamber of

Commerce v OSHA, 1980)

Prerequisites

An agency may through rulemaking create threshold standards that must be met before an applicant can qualify for a statutorily required hearing. (Federal Power Commission v Texaco, 1964)

Standard of bias

If there is clear and convincing showing that an agency member has an unalterably closed mind on critical matters in the rulemaking disposition, he must recuse himself from informal and hybrid proceedings. (Association of

National Advertisers v Federal Trade Commission, 1879)

Publication

A rule with criminal sanctions can become effective prior to the APA's requirement of a 30 day notice if there is a

good cause showing, that the necessity for immediate implementation outweighs any considerations of fundamental fairness. (United Staes v Gavrilovic, 1977)

Written, published standards equally applicable to all applicants must be established by an agency when it has received and operates under a broad delegation of power given it by the legislature. (Sun Ray Drive-In Dairy, Inc

v Oregon Liquor Control Commission, 1973)

Regulatory Analysis

A statement of basis upon which a rule was created must show the factual, legal, and policy foundations for the action take, that the order is supported by the agency's materials, and that it is reasonably related to the appropriate statute. (California Hotel & Motel Association v Industrial Welfare Commission, 1979)

An agency must demonstrate its consideration of the comments received and explain how the policy choices embodied in a rule fulfill the relevant statutory objectives, when promulgating a rule following notice and comment proceedings. (Independent U.S. Tanker Owners Committee v Dole, 1987)

Feasibility - Cost-Benefit Analysis

A cost-benefit analysis is not determinative, nor must one be made, in determining the feasibility of a proposed rule. (American Textile Manufacturers Institute v Donovan (The Cotton Dust Case), 1981)

Ex parte Communications

Informal Hearing

Ex parte communications made before issuance of a notice of proposed rulemaking do not have to be made public, unless it forms the basis for agency actions. Those occurring after the issuance of a formal notice must be disclosed so interested parties may respond. (Home Box Office, Inc v Federal Communications Commission, 1977)

Ex parte communications will only invalidate a rule made by an informal rulemaking proceeding when of the resolution of conflicting private claims to a valuable privilege. (Action for Children's Television v Federal

Communications Commission, 1977)

Hybrid Proceedings

Ex parte communications are permissible between agency members, staff advocates, and outside consultants, unless prohibited by statute. (United Steelworkers of America, AFL-CIO-CLC v Marshall, 1981)

Formal Hearing

No ex parte communications are allowed once notice of the proceedings has been issued. Any violation must be disclosed on the record. The decisionmaker may excuse the violation if the violator can show cause as to why his interest should not be adversely affected. Interested parties can include family, friends and neighbors.

Voiding Factors

Formal proceedings are voidable when blemished by improper ex parte communications that irrevocably taint an agency's decision. In determining such the court should consider: the gravity, the influence that resulted, if the party benefited, whether the offender disclosed the ex parte communication, and whether voiding the agency action would be useful. (Professional Air Traffic Controllers Org. v Federal Labor Relations Authority, 1982)

ADMINISTRATIVE ADJUDICATION

An administrative agency may constitutionally hold hearings, determine facts, apply the law to those facts, and order relief, so long as: 1) such activities are authorized by statute or legislation and are reasonably necessary to effectuate the agency's primary, legitimate regulatory purposes, and 2) the "essential" judicial power, (ie, the power to make enforceable, binding judgments) remains ultimately in the courts through review of agency determinations.

A jury trial in not required if these substantive constitutional limitations are observed. (McHugh v Santa Monica

Rent Control Board, 1989)

Types

Administrative adjudications are of two types, and occur in this order: 1) Institutional, where a member of the agency is the Decisionmaker. Hearings may be formal or informal. 2) Judicial, conducted by an administrative law judge These occur when a party appeals the outcome of a case where the Decisionmaker was a member of the agency. Basically it is an appellant type of process.

Exhaustion Rule (more rules under 'Timing of Review' below)

The filing of a complaint by an agency is a threshold determination, not an agency final action, and is not reviewable by an administrative law judge or the court system until all administrative remedies have been exhausted. (Federal Trade Commission v Standard Oil of California, 1981) (more exhaustion rules below)

Stare Decisis

Agencies are not bound by stare decisis, needing only to furnish an adequate explanation of a new interpertation.

(International Union, United Automobile Workers V NLRB, 1986)

Sources of the Right to a Formal Administrative Adjudication

The right to a formal administrative adjudication can be based upon a Federal or state statute, the Constitution or the Administrative Procedure Act

.

A party must be granted a formal hearing when the enabling statute requires the proceeding to be 'on the record'

(APA), Congress has clearly intended that a formal adjudication be held (Federal statute), or due process requires it (Constitution). (City of West Chicago v United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission, 1983)

APA Application

The APA strictures on administrative adjudications apply whenever an agency hearing is compelled by statute or by the Constitution. (Wong Yang Sung v McGrath, 1950)

Strict adherence

An agency must abide by its own rules and regulations in adjudicating a case, without regard to the fairness or equities of applying them to the case before it. (Reuters Ltd v Federal Communication Commission, 1986)

Impositions of penalties

Generally courts have protected liberty interests, proscribing infringing penalities by agencies, while granting agencies the right to impose monetary fines, ie property interests.

Criminal convictions

The adjudication of traffic violation may be transferred to an administrative agency, provided that conviction can result only in the imposition of fines with no imprisonment. (Rosenthal v Hartnett, 1975)

Felony offenses

The legislature may not delegate the right to define felony offenses to administrative bodies or department heads.

(State v Broom, 1983)

Money damages

A legislative grant of authority to award money damages is not an unlawful delegation of judical power to an administrative agency, provided such damage awards are reasonable and ultimately reviewable in court. (Vainio v

Brookshire, 1993)

Contempt

An administrative agency may not impose punishment for contempt absent constitutional provisions expressly granting such power. (In re Investigation of Lauricella, 1989)

Administrative arrest re: detention/deportation

Statutes authorizing administrative arrest to achieve detention pending deportation proceedings have been used

throughout the nation's history and thus they are constitutional. (Abel v United States, 1960) (under this argument we would still have slavery and a host of historically shameful ills.)

Avoiding a Formal Administrative Adjudication

Rules of general applicability

A formal hearing is not required for the pulmagation of a rule whose effect is of an adjudication if the rule is generic, affecting only the interests of a class, as opposed to affecting the interests of an individual person.

(Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewage District v Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, 1985)

"Jawboning" "Raised Eyebrows"

Agency members may influence the actions of private citizens in informal meetings between the citizens and the agency in order to effect a resolution and avoid a formal hearing. (Writers Guild of America, West, Inc v

American Broadcasting Cos, 1980)

Morgan I a) The one who decides must hear. No full hearing has been afforded unless the person who ultimately decides the issues has presided over the hearing. b) The officer who makes the determinations must consider and appraise the evidence which justifies the determinations, but need not have personally heard the witnesses give testimony, that evidence having been collected by another member of the agency. (Morgan v United States, Morgan I, 1936)

Morgan II

Prior to a formal hearing, affected parties must be given enough information such that they may pose meaningful counter-arguments. ( Morgan v United States, Morgan II, 1938)

Methods

Infirmities in agency methodology are not important provided the ultimate result cannot be said to be unjust and unreasonable. (Boston Electric v FERC, 1989)

Conflict of Laws

Circuit court supremacy/precedent

An agency may not willfully disregard a circuit court's decision; it may appeal the issue to the Supreme Court or seek a legislative remedy from Congress. (Stieberger v Heckler, 1985)

Administrative Sanctions

Where Congress has entrusted an administrative agency with the responsibility of selecting the means of achieving a statutory policy, a reviewing court may not overturn an administrative sanction designed to further that policy unless the agency's action is unwarranted in law or without justification in fact. An agency's inconsistent application of a sanction does not, standing alone, render the sanction chosen in a particular case unwarranted in law. (Butz v Glover Livestock Commission, 1973)

Investigation and discovery

Investigation

An agency action is investigatory when authorized by law other than the APA, relevant to the agency's general purpose, and not unduly burdensome. The party opposing the law under which the investigation is authorized must overcome presumptions that the action is neither unreasonable nor burdensome. (Appeal of FTC Line of Business

Report Litigation, 1978)

Discovery

An agency must produce evidence that the documents it requests go to a material issue or fact. (FTC v American

Tobacco Co, 1924)

Administrative Warrant

An administrative warrant must be supported by probable cause and a warrant, except in industries subject to a regulatory scheme containing detailed standards limiting the time, place and scope of administrative inspection.

(People v Scott, 1992)

Criminal cases

The use of an administrative warrant in a criminal case to circumvent the procedural protections of the

Constitution is prohibited. (Abel v United States, 1960)

Warrantless Inspections

A warrantless search of a business is permissible if the industry is heavily regulated, for a substantial government interest, necessary to further a regulatory scheme and the scheme must provide a constitutionally adequate substitute for a warrant in terms of certainty and regularity of it's application. (New York v Burger, 1987)

A warrantless administrative search of a business is permissible when a warrant would impede a regulatory scheme and regulation of the industry is pervasive. Commercial businesses are held to a lower standard and the 4th

Amendment does not automatically apply to them. (Donovan v Dewey, 1981)

A statute authorizing warrantless administrative searches is not invalidated by the fact that a police officer may locate evidence to be used in a criminal trial. (New York v Burger, 1987)

The 4th Amendment prohibits warrantless administrative searches except in heavily regulated businesses.

(Marshall v Barlow's Inc, 1978)

Subpoenas

To authorize subpoenas, an agency must show the investigation is properly authorized by Congress, is seeking relevant documents and the subpoena is reasonable in its specificity of time, place, and manner. There need not be a complaint pending. (Oklahoma Press Publishing v Walling, 1946)

An agency may define the scope of and issue subpoenas without first receiving judicial approval if the enabling statute directs the agency to conduct investigations of violations of law. (Endicott Johnson v Perkins, 1943)

The proper scope of an agency subpoena is: the records sought may reasonable relate to matters that are properly the subject of agency actions, reasonably relevant within the agency's authority, not unreasonably burdensome, and sufficiently definite. (Belle Fourche Pipeline v United States, 1983)

Defenses to subpoenas

Lack of jurisdiction

A jurisdictional inquiry in a subpoena enforcement proceeding is appropriate only if the lack of jurisdiction is so clear that to enforce the subpoena would result in an abuse of power. (EEOC v Kloster Cruise, 1991)

A Federal court does not have subject matter jurisdiction over a pre-enforcement challenge to an administrative subpoena as until the agency has filed for enforcement of the subpoena the issue is not ripe for review. (Texas

Lawyers Insurance Exchange v Resolution Trust Corp, 1993)

Procedural irregularity

Unreasonably broad

Privileged information

Record keeping

To allow reviewing courts to judge whether agency action was arbitrary, capricious or otherwise illegal, a statement of findings and reasons must be given and must explain why allowable exemptions were inapplicable to a case. (Matlovich v Secretary of the Air Force, 1978)

An agency need not provide an independent statement if it specifically adopts an administrative law judges' opinion that sets forth adequate findings and reasoning. (Armstrong v Commodity Futures Trading Commission,

1993)

5th Amendment defense

A corporation has no 5th Amendment defense and must comply with a subpoena duces tecum, even if the records being produced may be incriminating to persons named within the documents nor can they resist the subpoena on a

5th Amendment claim. (Braswell v United States, 1988)

Evidence

Evidentiary Hearing

An evidentiary hearing must be held, despite the absence of issues of fact, when the agency action seems to run counter to the public interest. (Office of Communication of the United Church of Christ v Federal

Communications Commission, Church of Christ I, 1966)

Multiple Agency Use

The evidence collected by one agency may be used by another agency in making it's own determination of the same issue. Here, determination by one agency of malpractice and a disciplinary hearing by another agency for that malpractice. (Guerrero v New Jersey, 1981)

Facts not in evidence

An agency may not make adjudicative decisions based on facts not in evidence except if the agency reveals those facts and gives the parties an opportunity to rebut. (United States v Abilene & Southern Railroad, 1924) (same rule for predictions, under Ohio Bell v PUC, 1937) Market Street Railroad v Railroad Commission, 1945 narrows this to prejudicial facts which were relied on by the agency.

Hearsay

The nature of hearsay affects its weight, but not its admissibility in an administrative hearing. (Reguero v Teacher

Standards Commission, 1990)

Residuum Rule

Hearsay evidence is admissible but findings of fact cannot be based exclusively on hearsay, they must be supported by a residuum of legal evidence competent in a court of law. (Wagstaff v Department of Employment Security,

1992)

Where a substantial right is at stake, there must be at least a residumm of evidence that would be admissible in civil court to uphold an agency decision. (Trujillo v Employment Security Commission, 1980)

Substantial inadmissible evidence

Federal agencies may make decisions solely on evidence not admissible in civil court if it is substantial and if admissible evidence was available yet not properly requested by opposing parties. (Richardson v Perales, 1971)

Agency decisionmakers may disregard testimony and evidence before them as the see fit. (Market Street Railroad

v Railroad Commission, 1945)

Official notice--assume facts not in evidence

When an agency takes official notice of legislative and factual issues in an adjudication, due process requires the agency to notify the parties and provide opportunity for rebuttal, unless the significance of underlying facts is within lay comprehension. (Franz v Board of Medical Quality Assurance, 1982)

Official notice of a material fact is permitted subject to opportunity to dispute the fact's accuracy by interested parties. (Boston Edison v FERC, 1989)

Material fact must be of a type appropriate for official notice. (Union Electric v FERC, 1990)

An agency should take notice of an adjudicative fact whenever it knows of information that would be useful in making a decision. The agency has reviewable discretion to take notice and to allow rebuttal evidence. However, the agency's discretion must be exercised in such a way as to be fair in the circumstances. (Castillo-Villagra v INS,

1992)

Exclusionary Rule

Evidence gotten in violation of the 4th Amendment, subject to the Exclusionary Rule, is admissible in an administrative proceeding if the social benefit of its admission outweighs the costs of excluding it. (Powell v

Secretary of State, 1992)

Evidence gotten in violation of the agency's own rule, but not in violation of the Constitution nor of a statute, is admissible in a subsequent criminal court proceeding. (United States v Caceres, 1979)

Judge as witness

An administrative law judge may only use information gained from the record and in the capacity of a judge, not as a witness, nor from information gained outside the proceeding. (Banegas v Heckler, 1984)

Expert testimony

A professional review board, possessed of appropriate expertise and capable of drawing its own conclusion and inference may disregard expert testimony, relying on their own expertise in reaching factual findings. (In re

Griffith, 1991)

Decision on partial testimony permissible

An administrative decisionmaker need not read nor hear all of the testimony on which their decision is based.

(New England Telephone & Telegraph Co v Public Utilities Commission, 1982)

Impermissible reliance on summation

An administrative tribunal may not rely upon a hearing officer's rendition or summary, written or oral, of testimony, but must make findings of fact based upon their own independent review of the evidence. (Stoffel v

Department of Economic Security, 1989)

New evidence

An administrative law judge may not admit newly discovered evidence but may remand the case to the agency for its consideration. (Eads v Secretary of Health and Human Services, 1993)

Preponderance of the evidence

APA requires preponderance of the evidence as the standard of proof with the burden on the claimant, rejecting the

"true doubt" rule. (Maher Terminals v Director, Office of Worker's Compensation Programs, 1993)

Preclusion

When a state agency properly resolves disputed issues of fact in an adjudication, federal courts must give the agency decision preclusive effect, unless Congress intended otherwise. (University of Tennessee v Elliott, 1986)

Collateral Estoppel

Re-litigation by the government of the same issue already litigated against the same party involving virtually identical facts is precluded under the Doctrine of Mutual Defensive Collateral Estoppel. (United States v Stauffer

Chemical Co, 1984)

Offensive Estoppel

Although in state of flux, generally, claims based on a theory of estoppel, against the Federal or a state government, are precluded.

Decisonmakers & Administrative Law Judges

Administrative law judges preside in Article I courts. Appointments do not require approval of the Senate. Just as the President has the right to appoint Article III judges, the heads of agencies in their quasi-executive capacity appoint the administrative law judges. However, a President cannot overrule the decision of an Article III justice, while the head of an agency can overrule the decision of an administrative law judge. The amount of authority an administrative law judge may exercise varies state to state. The hearing at which an administrative judge presides is equivalent to a bench trial in the Federal and state court system.

The term "decisionmaker" applies to both administrative law judges and the member of an agency who performs in the role of a decisionmaker in the affairs of the agency.

Agencies may overrule administrative law judges if upon a preponderance of the evidence the agency determines the decision was incorrect. (Federal Communications Commission v Allentown Broadcasting Corp, 1955)

Decisionmaker Qualifications

Legal training for a decisionmaker is unnecessary where knowledge of the law is not crucial to the decision making process. A decisionmaker must be unbiased, but not necessarily government appointed. (Schweidker v McClure,

1982)

Decisional independence

The APA vests ALJs with a limited right of decisional independence and freedom from interference in their decisionmaking. An ALJ has standing to sue for infringement of this right under a theory that an ALJ has a personal interest in their right to non-interference in their decisionmaking. (Nash v Califano, 1980)

Presumption of integrity of a Decisionmaker

To overcome the presumption of the agency decisionmakers integrity there must be evidence that the risk of unfairness is intolerably high by the member of the agency conducting both investigations and the adjudication.

(Withrow v Larkin, 1975) of an Agency

If the presumption of agency integrity is overcome, an agency may be disqualified from adjudicating an issue it investigated. (Ash Brove Cement Co v Federal Trade Commission, 1978)

'Good Cause' Removal

An ALJ is subject to performance-based standards. Failure to adhere to agency policy, governing law, and the frequency of reversals based on such failures, can establish a good cause for removal. (Social Security

Administration, Office of Hearing and Appeals v Anyel, 1993)

Prejudgment and prior exposure

Prejudgment of the precise facts requires disqualification of an administrative adjudicator. Prejudgment of the law or the agency's policies is not grounds to disqualify. Nor is it that the adjudicator was exposed to or investigated the facts at issue prior to the proceeding. (Central Platte Natural Resources District v Wyoming, 1994)

Administrative adjudicators must disqualify themselves if a disinterested observer could conclude the agency has in some measure adjudged the facts as well as the law of a particular case in advance of hearing. (Cinderella

Career and Finishing Schools, Inc v Federal Trade Commission, 1970)

Bias

Closed Mind

If there is clear and convincing showing that an agency member has an unalterably closed mind on critical matters in the rulemaking disposition, he must recuse himself from informal and hybrid proceedings. (Association of

National Advertisers v Federal Trade Commission, 1879)

Commonality

The mere existence of a cultural, racial,or sexual commonality between a decisionmaker and a party does not establish bias. (Andrews v Agricultural Labor Relations Board, 1981)

Pecuniary Interest

Any adjudicator with a pecuniary interest in the outcome of the adjudication must be disqualified due to bias.

(Gibson v Berryhill, 1973)

Will to win

A decisionmaker is precluded if he is involved in the case, or in a factually related case, has ex parte information, or has developed a 'will to win' regarding the case. (Grolier, Inc v Federal Trade Commission, 1980)

Ex parte communications

Ex parte communication are prohibited when the agency action resembles a judicial action. Ex parte meetings between an agency and White House officials will not invalidate an agency action unless the agency is one

'independent' of the executive branch. Such meetings between an agency and congressional officials are improper if there was congressional pressure that the agency consider factors not made relevant by the applicable statute and the agency was affected by the pressure. (Sierra Club v Costle, 1981)

Voiding Factors

Formal proceedings are voidable when blemished by improper ex parte communications that irrevocably taint an agency's decision. In determining such the court should consider: the gravity, the influence that resulted, if the party benefited, whether the offender disclosed the ex parte communication, and whether voiding the agency action would be useful. (Professional Air Traffic Controllers Org. v Federal Labor Relations Authority, 1982)

Rule of Necessity

A judge who would otherwise be disqualified, or who must recuse themselves, may conduct a proceeding if necessary because there is no other qualified judge available.

Public Participation

Petitions

An agency can be forced to institute rulemaking proceedings when a significant factual reason that previously had been given to deny a petition to institute rulemaking procedures has been removed, or when required to do so by law. (WWHT, Inc, et al v Federal Communications Commission, 1981)

If a petition for reconsideration of a previous proceeding, on the grounds of 'material error', is denied, the order denying the rehearing is not itself reviewable. (ICC v Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers, 1987)

If a private party makes a complaint to an agency, with allegations against a 3rd party outside of the agency, the

3rd party is entitled to a clear statement on the theory on which the agency will proceed and an opportunity to present a defense. (Yellow Freight System v Martin, 1922)

Intervention

An intervener need only show a legitimate interest distinct from the public at large. A legitmate interest includes but is not limited to one of an economic nature. (Office of Communication of the United Church of Christ v

Federal Communications Commission, Church of Christ I, 1966)

Negotiation

Transcripts

The administrative agency need not provide transcripts of a previous proceeding to an appellant court. A party who requests transcripts, is entitled to them, at their own expense. (Gearan v Department of Health and Human

Services, 1988)

JUDICIAL REVIEW BY FEDERAL OR STATE COURTS

Restraints on the court

Specific standards for enforcement impermissible

A court may not require an agency to follow a specific standard in enforcing its statutory obligations, not mandated by statute. An agency was wide discretion in how it is to enforce its obligations. (Federal Communications

Commission v WNCN Listeners Guild, 1982)

Bad faith requirement

Courts may not require administrators to testify about their rulemaking decisions without a strong preliminary showing of bad faith. (National Nutritional Foods Association v Food & Drug Administration, 1974)

De Minimus -- court created exception

A court should not create a 'de minimis' exception to a statute if it thwarts the statutory command; it must be interpreted with a view to implementing the legislative design. Notwithstanding the plain meaning of a statute, a court must look beyond the words to the purpose of the Act, where its literal terms lead to absurd or futile results.

(Public Citizen v Young, 1987)

Deference

"Judge Knows Best"

Questions of law

Independent judgment

Few specific fact situations

De Novo review

Unfair and Inadequate

A reviewing court may remand a case where the administrative judge failed to develop the administrative record fully and fairly, even though no one error, standing alone, would suffice to set aside the administrative determination as a matter of law. (Rosa v Bowen, 1988)

"Agency is the Expert"

Questions of fact

Substantial evidence

Clearly erroneous standard

Agency discretion: application of law to facts

Interpretation Deference

When reviewing the application of law to facts, a court must determine whether the statute entrusts interpretation of the law to agency discretion. If the agency is responsible for defining a broad term, then judicial review will be deferential. If not, then the court may substitute its judgment. (McPherson v Employment Division, 1979)

Delegated discretion

An agency's discretion to interpret a statute is limited by its congressionally delegated authority. (Addison v Holly

Hill Fruit Products, 1944)

Judicial overview of agency conduct

Where an agency's findings meet the statutory requirement for initiating formal agency action, a court may review the findings and direct the agency to being the administrative process requested. Courts will defer to the agency's fact findings, but will ensure that the standards used to make decisions conform to the legislative purpose and are uniformly applied. (EDF v Ruckelshaus, 1971)

Statutory modification

When a statute permits an agency to 'modify' certain aspects of a regulatory regime it has authority to change it moderately or in minor fashion. Statutory language granting the power to 'modify' does not include the authority to make basic and fundamental changes in the statutory scheme. (MCI v AT&T, 1994)

Appointed Administrator

Absent an agency with statutory jurisdiction, an appointed administrator's guidelines on a subject are useful to the court but not controlling. (Skidmore v Swift, 1944)

Hard look Doctrine

Hard-Look Doctrine is a principle of Administrative law that says a court should carefully review an administrative-agency decision to ensure that the agencies have genuinely engaged in reasoned decision making. A

court is required to intervene if it “becomes aware, especially from a combination of danger signals, that the agency has not really taken a ‘hard look’ at the salient problems.” The Administrative Procedure Act instructs federal courts to invalidate agency decisions that are “arbitrary” or “capricious.” Close judicial scrutiny helps to discipline agency decisions and to constrain the illegitimate exercise of discretion.\

Balancing factors

Where an agency has considered all relevant factors and the challenged findings are supported in the record, a court has no power to substitute its judgment for the agency's result, even if the court would have balanced the factors in a different fashion and achieved a different result. (Scenic Hudson Preservation Conf v FPC, II, 1971)

Mandatory hearing deadlines

Federal courts may not issue injunctions imposing mandatory deadlines for agency hearings, since Congress has expressly rejected this. (Heckler v Day, 1984)

Order modification

Absent abuse of discretion, a reviewing court may not modify a valid administrative order. (Moog Industries v

FTC, 1958)

Interests

Protected versus Privilege

A protected right is commonly known as an interest or protected interest. Traditionally, property rights were limited to property that could be actually owned. Abstract interests were privileges, not rights. Until Goldberg.

The distinction between privilege and right is abolished. (Goldberg v Kelly, 1970)

Constitutional due process interests versus statutorily created interests

Due process interests are derived from the Constitution. States and the Federal government may also created protected interests by statute. Protected interests can fall into 2 categories, those requiring a pre-termination hearing, and those in which a post-termination hearing is sufficent.

Hearing Rights

A hearing must occur before termination of benefits and need only provide the recipient an opportunity to present oral arguments and evidence on questions of fact, confront or cross-examine witnesses, counter opposing evidence, and retain an attorney before an impartial decisionmaker who must produce a record of his reasons behind his determination. (Goldberg v Kelly, 1970)

All protected rights, even those created by the state, require notice and an opportunity to be heard, as well as a

Mathews analysis. Procedural aspects of a state law will be analyzed separately from the substantive right created.

(Cleveland Board of Education v Loudermill, 1985)

Substantive versus Procedural Rights

Where legislation creating a protected interest concentrates on procedural measures, the substantive right may not be considered separately. (Arnett v Kennedy, 1974)

Mathews

The determination of whether an evidentiary hearing is required before the final determination of benefits depends on the weight of 3 factors: 1) how the private interest will be affected, including degree of loss and length of loss,

2) the risk of an erroneous decision, including necessity of oral presentations, the rate of reversal after judicial review, and possible alternatives to the present procedure, 3) how the governmental interest will be affected, including the incremental costs of pre-determination hearings, and the burden on scarce fiscal and administrative resources. (Mathews v Eldridge, 1976)

Public interest imposed limitations

All private property and privileges are held subject to limitations that may reasonable be imposed upon them in the public interest. (Air Line Pilots Association v Quesada, 1960)

Protected Interests

Constitutionally protected behavior

The government may not terminate or refuse to renew employment on the basis of an employee's constitutionally protected behavior. (Perry v Sindermann, 1972)

Liberty

Prisoner Rights-Solitary Confinement

Where the law uses mandatory language, and requires specific pre-conditions before imposing solitary confinement, a liberty interest is created.

Property

Welfare

The recipient of welfare entitlements has a protected property interest in the continued receipt of those benefits and, thus, is entitled to an evidentiary hearing before benefits are terminated. (Goldberg v Kelly, 1970)

Trade Secrets

Trade secrets are protected property interests.

(Ruckelshaus v Monsanto, 1984)

Employment Contracts

A state employment contract does not constitute a constitutionally protected interest; thus, due process need not be afforded prior to its termination. (Board of Regents of State Colleges v Roth, 1972)

When a government employee may not be terminated without "cause", state law has created a property interest in freedom from unlawful termination. (Cleveland Board of Education v Loudermill, 1985)

Diminished Expectation of privacy--required recordkeeping

No 4th Amendment 'privacy' claim may be asserted against an administrative subpoena duces tecum for records required to be maintained by law and subject to agency inspection, because there is a diminished expectation of privacy in these types of records. (Craib v Bulmash, 1989)

Not Protected

Privileges

Indirect Benefits

Prisoner Rights

As long as conditions do not violate constitutional norms, the Court will not reviw whether an inmate's treatment violates the Due Process Clause. (Hewitt v Helms, 1983)

Required Records

Records statutorily required to be kept cannot be withheld under a 5th Amendment claim of self-incrimination, when the recordkeeping is intended to promote a legitimate regulatory aim, is not directed at activities or person inherently 'criminal', and only requires minimal disclosure of information of a kind customarily kept in the ordinary course of business. (Craib v Bulmash, 1989)

5th Amendment Eminent Domain

A taking of property in violation of the 5th Amendment by agency action can be any interference with reasonable investment-backed expectations, also based on the character of the action and it's economic impact. (Ruckelshaus

v Monsanto, 1984)

Public Use

An agency 'taking' occurs for public use, requiring just compensation, where Congress has determined that the action is beneficial to the public good. (Ruckelshaus v Monsanto, 1984)

Due Process Hearing Rights

Minimum Process

There must be notice and an opportunity to be heard before any property interest may be taken by administrative action. (Southern Railroad v Virginia, 1933)

Adjudicative exclusivity

Although a proposed rule may affect due process interests, due process requirements of a trial type hearing apply only to a agency's adjudicative, rather than legislative or rulemaking, functions.

Legislative vs Adjudicative Test

A rule which affects private, due process, interests must meet to two tests to be legislative rather than adjudicative:

1) must not be directed at a single person or corporation, and 2) must not be dependent upon a determination of contested facts. (Anaconda v Ruckelshaus, 1972)

Evidentiary hearing

The lack of providing for a private party to an action an evidentiary proceeding at the administrative level is not a denial of due process providing there is an opportunity for the party to obtain a de novo judicial review of the agency's decision. (Haskell v Department of Agriculture, 1991)

Oral testimony

The due process clause does not require that oral testimony be heard in every administrative proceeding in which it is tendered. (FDIC v Mallen, 1988)

Mathews analysis requirement

A Mathew analysis is required in every case involving protected rights. The first factor (the private interest) should include an analysis of historical limitations of the interest. (Ingraham v Wright, 1977)

'Meaningful Explanation'

A claimant with a property interest in continued receipt of government benefits must at least receive information regarding the original decision, a reasonable time and opportunity to present evidence supporting that claimant's position and, after the hearing, a 'meaningful explanation' of the final decision. (Gray Panthers v Schweiker I,

1980)

Livelihood procedural rights

Because the pursuit of a livelihood may require the continuous possession of a driver's license, prior to it's suspension there must be notice and opportunity for a hearing about the issues appropriate to the nature of the case.

A driver's license is a property interest. (Bell v Burson, 1971)

Delayed Post-deprivation hearing--factors affecting Constitutional deficiency

In the determination whether a delayed post-deprivation hearing was constitutionally deficient, the court must consider 1) the importance of the interest 2) the harm to the interest occasioned by the delay 3) the government's justification offered and it's relation to the underlying governmental interest 4) the likelihood the interim decisions may have been mistaken. (FDIC v Mallen, 1988)

Revocation by referendum

Due process rights cannot be revoked by a referendum (ie, by ballot in an election). (Brookpark Entertainment v

Taft, 1991)

Prejudgment attachment of property

Where a statute authorizes a private party to seek the state's assistance in attaching the property of another prior to judgment, the requirements of due process must be satisfied. A plaintiff's good faith belief in the merits of his case does nothing to protect the property owner's significant interest from unwarranted attachment, and thus good faith alone fails to satisfy constitutional due process concerns. A reviewing court must consider 1) the private interest that will be affected 2) the risk of erroneous deprivation and 3) the interest of the party seeking the prejudgment remedy. (Connecticut v Koehr, 1991)

Hearing 'before' a judge

Where a statute requires a hearing to be conducted 'before' an administrative judge, it must be in his actual physical presence. (Purba v INS, 1989)

Irrebuttable presumptions

It is forbidden by the Due Process Clause to use an irrebuttable presumption when the presumption is not necessarily or universally true in fact, and when the State has reasonable alternative means of making the crucial determination. (Stanley v Illinois)

Exceptions

Generally applicable rules

Where all concerned are treated equally by a statute, due process does not require an opportunity to be heard. (Bi-

Metallic Inv v State Board of Equalization, 1915)

Benefit Levels

The due process clause of the 14th Amendment creates no property interest in a constant level of benefits and does not require Congress to maintain current levels of entitlements. (Atkins v Parker, 1985)

Emergencies

If not destroying the property may in itself constitute a nuisance, that property may be summarily destroyed without violating due process. (Northern American Cold Storage v Chicago, 1908) (putrid chicken rotting in warehouse case)

Waiver

The right of an opportunity to be heard at a hearing may be expressly waived, or impliedly by the lapse of time, such as by a limitation put on the time in which one can make a request for a hearing and then the failure to do so within the permitted time span. (National Independent Coal Operator's Association v Kleppe, 1976)

Business Relations

There is no protected property interest in having continued business relations with the government beyond that of being treated fairly by the government. (Gonzalez v Freeman, 1964)

Obtaining Judicial Review

Jurisdiction of the court

A party can obtain judicial review by the agency enabling statute, general jurisdiction statutes, if a federal question is at issue, or by a writ of mandamus.

Presumptively reviewable

Agency actions are presumptively reviewable. Review is only precluded expressly by statute or when an action is

"committed to agency discretion" and there is no law to apply. (Citizens to Preserve Overton Park v Volpe, 1971)

Private petitions

Refusal by an agency to initiate rulemaking proceedings upon request by a private petition must be accompanied by a public explanation to provide a means for a court to review the basis of an agency's decision not to institute rulemaking. (American Horse Protection Assn v Lyng, 1987) by Certiorari not permitted

A writ of certiorari may only be issued to review the decisions of inferior courts. Any attempt to use the writ for the purpose of reviewing an administrative order would be an invasion of the executive branch and cannot be permitted. Certiorari as a nonstatutory remedy has been eliminated. (Degge v Hitchcock, 1913 ) by APA, no

The federal APA does not, expressly or impliedly, confer an independent grant of subject matter jurisdiction for the federal courts to review agency actions. (Califano v Sanders, 1977)

Collateral Attack -- Mendoza-Lopez

A collateral challenge to the use of an agency deportation proceeding as an element of a criminal offense must be permitted where the agency proceeding effectively eliminates an alien's right to judicial review. (United States v

Mendoz-Lopez, 1987) (this was brought up in the case they argued last week, party had the right to attack collaterally and use of writ of mandamus, and had done neither...Justices mentioned this case a few times. week of

Oct 10, 2011)

Sovereign Immunity

The Board of Claims Act waives constitutional immunity for state governments, but retains the common law sovereign immunity traditionally granted to local governments in the performance of their general public obligations. (Commonwealth of Kentucky, Dept of Banking and Securities v Brown, 1980)

Government Immunity

A government agency, or an agency acting as a corporation, is not subject to the Doctrine of Estoppel nor is it vicariously liable for an unintentional misrepresentation by an agent of the agency. Even when conducting business in the same manner as a private enterprise. "Men must turn square corners when they deal with the government."

(Federal Crop Insurance Corp v Merrill, 1947)

Damage Action

Federal and state officials have only a qualified immunity from damages liability. Federal officials involved in adjudication are absolutely immune from liability. (Butz v Economou, 1978)

'Outer perimeter' liability test

All federal employees are absolutely immune from common law tort liability for acts performed "within the outer perimeter" of their line of duty. (Barr v Matteo, 1959)

Discretionary functions exemptions - FTCA

Discretionary acts in the performance of government functions, including policy-making and implementation by subordinate federal officials, are exempt from liability by the FTCA. (Dalehite v United States, 1953)

Discretionary functions liability

Government officials performing discretionary functions are shielded from liability for civil damages as long as their conduct does not violate clearly established statutory or constitutional rights of which a reasonable person would have known. (Harlow v Fitzgerald, 1982)

Acting beyond scope

Judicial relief is available to a party injured by a government officer acting beyond the scope of his express or implied statutory authority. (American School of Magnetic Healing v McAnnulty, 1902 )

Judicial Review Preclusion

Clean and convincing evidence standard

A showing of 'clear and convincing evidence' that Congress intended to preclude judicial review is necessary to overcome the strong presumption that agency action is reviewable. (Bowen v Michigan Academy of Family

Physicians, 1986)

Preclusion ineffectual

Judicial review may be available in the fact of explicit statutory language to the contrary where the constitutional right of the party is implicated or the agency has acted illegally, unconstitutionally , or in excess of its jurisdiction.

(DEP v Civil Service Commission, 1991)

Applicable rules precluded

Statutes precluding judicial review of claims adjudications also preclude review of agency rules applicable in those adjudications. (Gott v Walteres, 1985)

Intent to make final