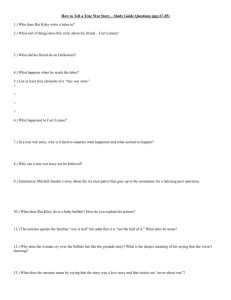

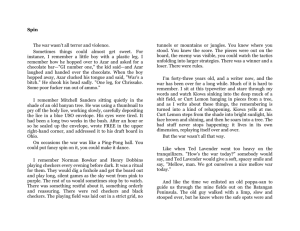

The Things They Carried

advertisement