the effects of eliminating the concept of fourth amendment standing

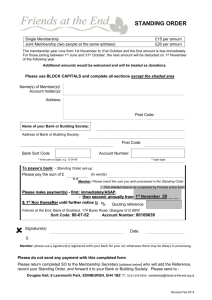

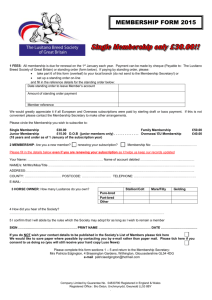

advertisement