Concept-Based Teaching: A Guide to Big Ideas in Education

Getting the Big Idea: Concept-Based Teaching and Learning

“Transforming Learning Environments through Global and STEM Education” August 13, 2013

What is concept-based instruction?

Concept-based instruction is driven by “big ideas” rather than subject-specific content.

By leading students to consider the context in which they will use their understanding, concept-based learning brings “real world” meaning to content knowledge and skills. Students become critical thinkers which is essential to their ability to creatively solve problems in the 21 st

century.

By introducing students to universal themes and engaging them in active learning, concept-based instruction: creates connections to students’ prior experience. brings relevance to student learning. facilitates deeper understanding of content knowledge. acts as a springboard for students to respond to their learning with action.

(Erickson 2008)

Why is it worth our time?

Concept-based instruction, by placing the learning process in the “big picture” context of a transdisciplinary theme, leads students to think about content and facts “at a much deeper level” and “as a practitioner would in that discipline” (Schill & Howell 2011). According to the International Baccalaureate Organization (IBO), teaching and learning that is driven by overarching concepts necessitates that students transfer their knowledge between personal experiences, learning from other disciplines, and the broader global community. Thus, concept-based instruction mandates more critical thinking at increasingly higher levels of Bloom’s taxonomy .

(Erickson 2012)

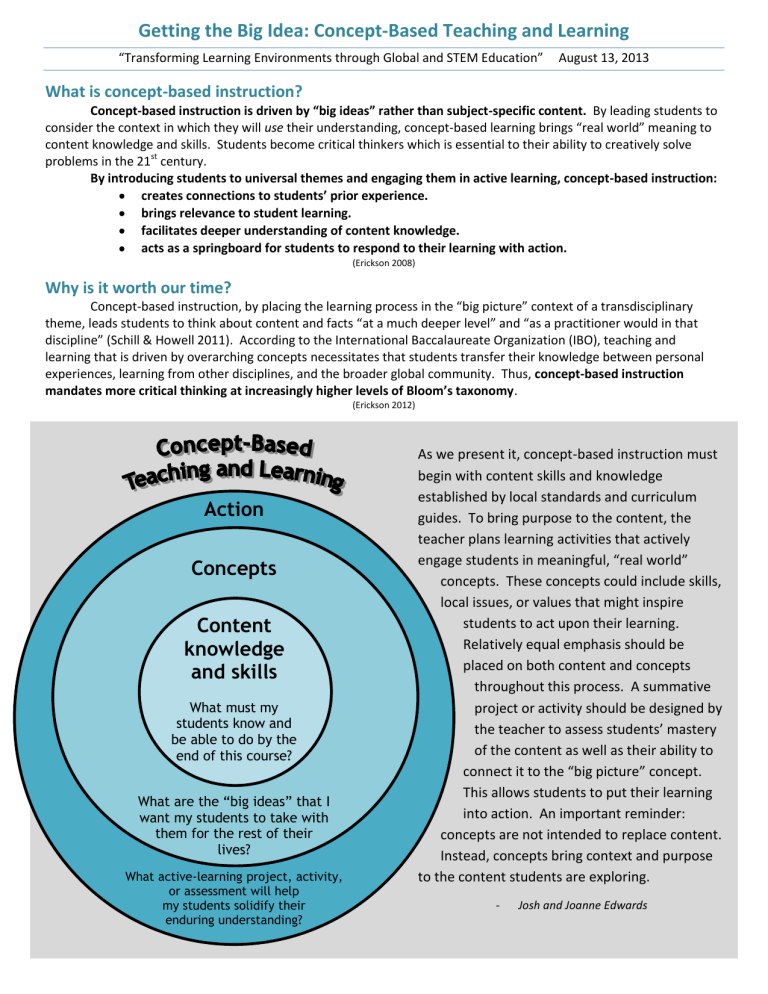

As we present it, concept-based instruction must

Action

begin with content skills and knowledge established by local standards and curriculum

Concepts

guides. To bring purpose to the content, the teacher plans learning activities that actively engage students in meaningful, “real world”

Content knowledge and skills

What must my students know and be able to do by the end of this course? concepts. These concepts could include skills, local issues, or values that might inspire students to act upon their learning.

Relatively equal emphasis should be placed on both content and concepts throughout this process. A summative project or activity should be designed by the teacher to assess students’ mastery

What are the “big ideas” that I want my students to take with them for the rest of their lives?

What active-learning project, activity, or assessment will help my students solidify their enduring understanding? of the content as well as their ability to connect it to the “big picture” concept.

This allows students to put their learning into action. An important reminder: concepts are not intended to replace content.

Instead, concepts bring context and purpose to the content students are exploring.

Josh and Joanne Edwards

What is a concept? (The concept-topic divide)

A common problem among teachers who want to bring concepts into their classroom is defining exactly what a concept is … and is not . An important distinction to note is the difference the topics that our curriculum mandates we include in our instruction, and the concepts that help connect that set of knowledge and skills to students’ lives.

According to Lynn Erickson, concepts are universal, timeless, abstract, and move students toward higher levels of thinking. Concepts are broad ideas that transcend the perspectives and limits of any specific subject-area. A concept is something that can be taught in any classroom, no matter what the content includes.

Topics Concepts Topics Concepts

The Human Body

Slavery

Author’s Purpose

Geometrical Translations

Verb Conjugation

Desktop Publishing

Systems

Oppression

Perspective

Change

Relationships

Communication

Surrealism

Percussive Rhythms

Stage Combat

Team Sports

Sewing

Horticulture

Symbolism

Pattern

Conflict

Communities

Aesthetics

Sustainability

(Bray 2012 and Erickson 2007, 2008, and 2011)

How do I choose concepts that are right for my teaching?

The concepts a teacher chooses to utilize will heavily depend on his or her content, the age, experiences, and diversity among the students, and personal goals and values for teaching. What is most important is that you, the teacher, are invested in helping students explore the “big ideas” you choose, and that the concepts you choose are relevant for your students.

There is also a variety of options you can consider in the kind of concepts you choose to use with your students.

For example, you might choose content-specific concepts (still broader than topics) that easily connect to the information students are learning. This might be a great place to start, especially if you feel this approach to instruction will require some “getting used to.” Or, you might choose a set of thinking or learning skills that you want your students to master by the time they leave your class, like “intercultural awareness” or “persisting.” Another approach could be choosing broad, universal concepts that transcend all subject-areas. These universal concepts often have complex social implications that can lead to critical and reflective thinking among your students. ( See the chart below for some specific examples .)

Whatever type of concepts you choose, consider ways that you can make them visible in your class’s physical space as well as the learning activities you plan.

Content-centric concepts

In a Social Studies classroom, use the Five Themes of

Geography as ongoing concepts that show up in each unit and get special attention in your teacher. Concepts would include Location, Place, Human-

Environmental Interaction,

Movement, and Region.

Skill-centric concepts

At the beginning of each week, introduce and discuss one of

Costa and Kallick’s 16 Habits of

Mind . Then, have your students reflect on how they utilized that

Habit at the end of the week.

The 16 Habits include Persisting,

Listening with Understanding and Empathy, Thinking about

Thinking, and Applying Past

Knowledge to New Situations, among others.

Universal concepts Course-long themes

In each unit, use one of IBO’s newly published 16 MYP Key concepts to consider the broader impacts of the content students are learning. Do this by starting class discussions and using media to prompt debates about the meaning of a specific conceptual term, its repercussions in the “real world,” and how students think it connects to the content they are learning. The Key concepts include Change, Form, Identity, and Global Interactions, among others.

Developing the long-term theme of Global issues , connect each unit’s content with a specific human rights issue around the world. Create a community service opportunity to give students the chance to act upon their discussions of these themes. You might choose to focus on any number of global or societal issues including access to sufficient drinkable water, human trafficking, labor conditions, and access to quality, affordable medical care.

How do I adapt my teaching strategies to include these concepts?

While each teacher will have a unique approach to implementing concept-based instruction, a 2011 article in

Science and Children magazine outlines five basic steps to help teachers actually do concept-based learning with their students. Use this template, outfitted with the five steps, to start planning your concept-based unit.

Teacher name:

Course title and grade level:

Dates for teaching this unit:

1.

“Choose a topic of study” : Start with the content your students need to learn. (Maybe choose a unit that you already want to change or re-develop?)

What content topic(s) will this unit include?

2.

“Decide on a concept”

Thinking about this unit, what is the most important idea that you want your students to remember when they leave your class?

Try to summarize this “big idea” in one word.

: Use the questions below to develop what might serve as a good concept for this unit.

IBO calls this the “ enduring understanding .”

Is this a concept , and not a topic ?

Is this a concept that you value for your students to explore?

Are there any other “big ideas” that fit this content well that you might also want your students to consider?

What concept(s) will this unit explore?

Did you find your “big idea” for this unit?

If not, try choosing a “macroconcept” from a pre-established list that we’ve suggested, or create a concept map of the topic you are teaching and look for “big ideas” that emerge.

3.

“Develop essential understandings” : What do want your students to know by the end of the unit, on the factual and conceptual levels? By specifically writing down what you hope your students will learn about the content and the concept, you will clarify what you want to accomplish (making planning learning activities much easier!).

Using “ I can ” statements , list the key learning objectives you have for your students during this unit. These should include content and concept.

I can…

I can…

I can…

(Schill & Howell 2011)

4.

“Use inquiry-based investigations” : Give your students the chance to use their prior knowledge to solve a problem or explore a new idea first. Often, the “big ideas” show up all on their own! Then, follow up by introducing the unit concept and the topic of study. Keep bringing class discussions back to this concept throughout the unit, where appropriate.

What learning experiences will you use to help students connect the content and the concept in this unit?

5.

Assess both content and concept : By the end of the unit, give the students a chance to show you what they’ve learned. Either add a special activity that asks students to demonstrate their learning related to the unit concept, or blend this into your assessment of their content knowledge and skills by asking them to connect the two together.

How will you assess student learning of the content, concept, and the connections between them?

“Unit Concepts”

Divide the course up into specific units and choose one specific concept that fits well with that block of content.

Plan lessons, activities, and class discussions that integrate this concept into students’ learning during this unit and find ways to connect the concept to assessment throughout this unit as well.

“Overarching Concept”

“Core Concepts”

Choose a core set of concepts that will be introduced early in the course and then addressed and readdressed throughout the rest of the course. These reoccurring concepts can show up on a weekly or quarterly basis or even on an activity-by-activity basis.

What will conceptbased instruction look like in my classroom?

How will my students and I use these concepts?

Blend these approaches!

Find ways to use more than one of these methods to get your students thinking in context (or even, “ in concept !”). Introduce your class’s core themes at the beginning of the course, then focus on one at a time during each major unit. As the unit concepts build, lead your students to a central, main concept that ties them all together at the

Choose an overarching concept that you and your students will develop over the entire course, continuing to explore, discuss, develop, and reflect on this “big idea” in every unit. Each unit might examine this single concept in a slightly different way, like from a different perspective, or by studying a different aspect of the larger idea. end of the course!