GASB VERSUS FASB: USER PERCEPTIONS OF THE

advertisement

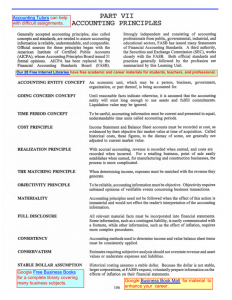

J. OF PUBLIC BUDGETING, ACCOUNTING & FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT, 9(2), 224-250 SUMMER 1997 GASB VERSUS FASB: USER PERCEPTIONS OF THE ALTERNATIVE FORMATS FOR PREPARING THE STATEMENT OF CASH FLOWS G. Robert Smith, Jr., Robert J. Freeman and Barry J. Bryan* ABSTRACT. This paper reports results of a survey that examines user perceptions of alternate formats of the Statement of Cash Flows (SCF) mandated by the Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB) and the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). The formats were compared using seven reporting issues. The findings indicate that users found the GASB SCF model to be superior to the FASB model for all issues. The study has implications for both standard-setting bodies. The GASB has already considered the results in developing a new reporting model for governmental entities. The FASB may at some point want to reconsider its SCF reporting requirements. INTRODUCTION There are two alternate formats for preparing the Statement of Cash Flows. One format is used in the private sector and is prescribed by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) in its Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 95, Statement of Cash Flows. The other is used in the public sector and is prescribed by the Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB) in its Statement No. 9, Reporting Cash Flows of Proprietary and Nonexpendable Trust Funds and Governmental Entities That Use Proprietary Fund Accounting. While the business sectors that use each statement are completely separate, the FASB model could be adapted for use in the public sector. ______________ *G. Robert Smith, Jr., Ph.D., CPA, and Barry J. Bryan, Ph.D., CPA, are Assistant Professors of Accounting at Auburn University; and Robert J. Freeman, Ph.D., CPA, is the Distinguished Professor of Accounting at Texas Tech University and, since 1990, a member of the Governmental Accounting Standards Board. Their teaching and research interests are in governmental accounting and auditing. Copyright © 1997 by PrAcademics Press GASB VERSUS FASB: USER PERCEPTIONS 225 Indeed, in the interim between the time the FASB issued its statement in 1987 and the GASB issued its statement in 1989, the FASB model was allowed in the public sector. The purpose of this study is to examine which model is superior for reporting cash flows in the public sector: the FASB model adapted for governmental reporting or the GASB model. A survey of users, preparers, and auditors was used to examine perceptions of the two models. As reported in the following sections, the respondents found the GASB model to be superior to the FASB model for reporting cash flows in the public sector. These findings may have major implications for both standard-setting bodies as they reexamine their respective financial reporting models. The article will consist of a brief review of the evolution of cash flow reporting standards, examine basic issues related to the FASB and GASB models, describe research design and findings, and finally present some conclusions about the two SCF models. LITERATURE REVIEW Cash flow reporting has been a Ahot topic@ for a number of years. Indeed, some form of cash flow or funds flow reporting has been in use since the 1860s. However, the debate has intensified in the last ten years as the two accounting standard setting bodiesCthe Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB) and the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB)Chave both issued accounting standards addressing cash flow reporting. The accounting standards at issue are: - Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 95, Statement of Cash Flows (FASBS 95), and - Statement No. 9 of the Governmental Accounting Standards Board, Reporting Cash Flows of Proprietary and Nonexpendable Trust Funds and Governmental Entities That Use Proprietary Fund Accounting (GASBS 9). Both these standards replaced Accounting Principles Board Opinion No. 19, Reporting Changes in Financial Position (APBO 19), issued in 1971. APBO 19 was the first accounting standard to require a funds flow statement in both the public and private sectors although there had been other attempts by in both the private sector (APBO 3, The Source and Application of Funds) and the public sector (National Committee on Governmental 226 SMITH, FREEMAN & BRYAN Accounting Bulletin No. 14, Municipal Accounting and Auditing and Governmental Accounting, Auditing, and Financial Reporting) to address cash flow and funds flow reporting. The Opinion required a Statement of Changes in Financial Position (SCFP) prepared on either a cash or working capital basis. FASBS 95 was extremely controversial when it was formulated and issued in 1987. There was considerable debate at the FASB over the requirements of statement of cash flows (SCF) standard. Arthur Wyatt resigned from the FASB because the Board elected to allow the use of the indirect method when preparing the SCF. Even when the standard was issued, it was only by a 4-to-3 vote. The dissenting Board members found fault with the classification of cash flows from interest and dividends received and interest paid as well as some format issues in the standard. These cash flow classifications are among the issues addressed in this study. The issuance of FASBS 95 left governmental reporting for business-type activities in a quandary. Should governments continue to use the SCFP as required by APBO 19? Or, should governments start presenting the FASBS 95 statement of cash flows? For a while, not even the GASB was sure. Initially, the Board stated that it would issue its own SCF standard, and that governments were to continue reporting using the SCFP requirements until the standard was issued. Then the GASB reversed its position, saying it would not issue a SCF standard, and instructed governments to follow the FASBS 95 requirements so long as the disclosure requirements of APBO 19 were met. Finally, the GASB decided to issue its own SCF standard. The GASB issued its SCF standard in 1989, after considerable discussion on whether the FASB model would be sufficient for governmental reporting. This standard did not have the unanimous support of the Board; it was issued by a 4-to-1 vote of the GASB members. Also, because the GASB model differs significantly from the FASB model in both form and content, many users questioned whether separate reporting models were needed for the public and private sectors. These differences are discussed later in this paper. The debate about the GASB model was acerbated further when the FASB issued Statement No. 117, Financial Statements for Not-for-Profit Organizations. Part of the debate then was whether these organizations should generally follow the private sector model or the public sector model. GASB VERSUS FASB: USER PERCEPTIONS 227 Ultimately, the FASB elected to use a SCF format similar to the one in FASBS 95. Prior to this research, no empirical study had examined whether users perceive a difference in the FASB and GASB SCF models for reporting cash flows. This article reports the results of research that examines user perceptions of these two models. RESEARCH ISSUES This study is based on the six pairs of issues that were directly related to differences between the two SCF models. This section summarizes these six issues and provides background on why the GASB and FASB SCF models are different. One other pair, #7, examines the recipient=s overall preference for one of the two models. Model Issue #1 This issue addresses reporting cash receipts for interest earned on investments and is one of the basic differences between the GASB and FASB models. The FASB model reports the cash receipts for interest earned on financial investments in the Operating Activities section. There was some discussion before the issuance of FASBS 95 on where this amount should be reported. In the Exposure Draft for the accounting standard the receipts were reported in the Operating Activities section. Some respondents stated that the receipts should more properly be reported in the Investing Activities section because the interest represents a return on those investments. (1) The FASB cites three principal reasons for maintaining the Operating Activities classification: - Almost all businesses classified cash receipts for interest as operating cash flows on the Statement of Changes in Financial Position (SCFP). - Interest received is commonly considered an operating cash flow by banks and other financial institutions. - The FASB perceived widespread support for the idea that the Operating Activities section should contain those items used to calculate net income to facilitate the reconciliation of net income to cash flows from operations (FASB, 1987). 228 SMITH, FREEMAN & BRYAN As noted earlier, this was one of the primary issues on which three of the FASB members dissented when the accounting standard was issued. The GASB model places the interest earned on investments in securities (equity and debt instruments that are not cash equivalents) in the Investing Activities section. The GASB also uses this section to report the purchase and sale of these investments. In the ABasis for Conclusions@ for GASBS 9, the Board stated: The nature of investing activity in the governmental environment is focused on the acquisition and disposition of debt and equity instruments of other entities rather than on the investment of ownership capital in capital assets. Therefore, it is more useful to reclassify investment earnings (interest and dividends) as inflows from investing rather than from operating activities. This presents a clearer picture of all the cash flows from investing activities and is consistent with the reclassification of interest expense discussed earlier. (GASB, 1989, paragraph 57) Thus, the GASB avoided some fundamental flaws found in the FASB=s support for placing interest earned in the Operating Activities section: 1. The FASB cited the widespread reporting of interest earned as operating cash flows on the SCFP. However, a review of SCFPs prepared from 1971 to 1987 revealed that very few were prepared using the Operating, Investing, and Financing sections allowed under APBO 19. Most SCFPs were limited to Sources and Uses of either cash or working capital, depending on the basis selected by the company. 2. The FASB stated that interest was an operating cash flow for banks and other financial institutions. This statement was true, but one must consider the nature of operations for a financial institution: to earn interest on investments. Corporations rarely report interest as operating revenue. Instead, a classified operating statement reports interest as an other or nonoperating revenue. An operating statement prepared for a government business-type activity also reports interest as nonoperating revenue. 3. The FASB supported its decision to report interest as an Operating Activity to facilitate the reconciliation of cash flows from operations to net income. The GASB avoided this problem by reconciling cash flows from operations to operating income rather than to net income. Model Issue #2 GASB VERSUS FASB: USER PERCEPTIONS 229 This issue addresses the problem of reporting the proceeds from debt issued to finance operating activities. The FASB SCF model reports all debt proceeds in the same section: Financing Activities. The FASB stated that this section includes A. . . obtaining resources from owners and providing them with a return on, and a return of, their investment; borrowing money and repaying the amounts borrowed, or otherwise settling the obligation; and obtaining and paying for other resources obtained from creditors on long-term credit@ (FASB, 1987, paragraph 18). The GASB made the decision to categorize debt proceeds in two sections depending on the purpose of the debt issue. For debt issued to support operations, the GASB model uses Noncapital Financing Activities. For debt issued to purchase capital assets, the GASB model uses Capital and Related Financing Activities. To support this classification, the GASB stated: Perhaps the most obvious difference [between public sector businesses and private sector businesses] is the absence of transactions with Aowners@ in governmental enterprises. Governmental enterprises do not sell stock, pay dividends, or engage in other transactions with owners; consequently, the significance of the Afinancing@ category as defined in [FASBS 95] is diminished. . . . Many governmental enterprise funds and public authorities finance their operations and manage their cash flow activities in a manner that makes a clear distinction between Aoperating@ and Acapital.@ Capital budgeting and long-range capital planning are common, and may even be required by law in some jurisdictions. Information about the cash inflows and outflows of a capital program is useful for identifying the level of capital spending and the nature and adequacy of the sources of funding for the projects. (GASB, 1989, paragraph 53) Hence, the GASB sought to distinguish between debt issued to support operations (Noncapital Financing Activities) and debt issued to acquire capital assets (Capital and Related Financing Activities). Model Issue #3 This issue addresses a government-unique problem of reporting transfer payments to governmental funds. Transfers between funds are not an issue in private sector financial reporting, so FASBS 95 did not discuss the issue. 230 SMITH, FREEMAN & BRYAN However, this analysis assumes that using the FASB model was an option, so reporting transfers is still an important consideration. Transfer payments between fundsCotherwise known as interfund transfersCcan represent significant cash flows. Interfund transfers also represent significant economic and political transactions for a government. Thus, the GASB recognizes two types of interfund transfers: operating transfers (the issue here) and residual equity transfers. In this survey, reporting an operating transfer from a proprietary fund is the analysis issue. The fund operating statement reports the transfers after revenues and expenses, but before net income. In theory, reporting transfers in the Operating Activities section is acceptable if one adopts the FASB criterion of including all elements used in the calculation of net income in that section. But since the GASB uses operating income as the reconciliation point for the Operating Activities section, reporting transfers between funds in the Noncapital Financing Activities section is more appropriate. The GASB includes these types of payments in this section by stating, ACash outflows for noncapital financing activities include ... cash paid to other funds, except for quasi-external operating transactions@ (GASB, 1989, paragraph 21, emphasis added).(2) Model Issue #4 The reporting of cash payments for long-term investments in marketable securities and capital acquisitions is the subject of this issue. As discussed previously in issue #1, the FASB model reports all long-term investments in financial securities and capital assets in the same section: Investing Activities. The FASB defined this section by stating, AInvesting activities include making and collecting loans and acquiring and disposing of debt or equity instruments and property, plant, and equipment and other productive assets, that is, assets held for or used in the production of goods or services by the enterprise (other than materials that are part of the enterprise=s inventory)@ (FASB, 1987, paragraph 15). There was no other discussion of this issue in FASBS 95. The discussion on issue #2 provided some support for the GASB decision to create separate sections for reporting financial investments and investments in capital assets. The GASB went on to state that, Athe Board believes an additional category for >capital and related financing= activities will provide useful information about the capital activities of governmental enterprises@ GASB VERSUS FASB: USER PERCEPTIONS 231 (GASB, 1989, paragraph 54). Therefore, this issue represents a principal difference between the two models. Model Issue #5 Issue #5 is very similar to Issue #1 in that it is a debt-related issue. This issue analyzes reporting cash paid for interest on debt. This issue is another fundamental difference between the GASB and FASB SCF models. In commenting on the responses received to the exposure draft for the SCF, the FASB stated: Some respondents to the Exposure Draft favored classifying interest paid as a cash flow for financing activities .... Those respondents generally said that interest paid, like dividends paid, is a direct consequence of a financing decision and thus should be classified as a cash outflow for financing activities. That is, both interest and dividends are returns on the capital provided by creditors and investors, and both should be classified with returns of those amounts because the distinction between returns of and returns on investment are largely irrelevant in the context of cash flows (FASB, 1987, paragraph 89). The FASB then provided the same three issues used to support the placement of interest and dividends received to support the placement interest paid. The GASB=s decision to separate noncapital financing transactions from capital and related financing transactions was discussed previously. The GASB provided further support for the distinction by stating: The financing category in [FASBS 95] includes cash inflows and outflows related to both capital and noncapital borrowing. Capital borrowing activity is another major element of the capital and related financing category. To show the complete picture of all cash inflows and outflows from financing, acquiring, and disposing of capital assets, it is necessary to include interest payments in this category rather than in the operating category. Similarly, interest on noncapital debt is classified as noncapital financing so that it is treated consistently with capital interest and gives a more complete picture of all inflows and outflows arising from noncapital debt transactions (GASB, 1989, paragraph 57, emphasis added). 232 SMITH, FREEMAN & BRYAN Also, as with interest revenue, the proprietary fund operating statement reported interest expense as a nonoperating item. Thus, the reconciliation of operating income to cash flows from operations provided further support for excluding interest payments from the Operating Activities section. Model Issue #6 This issue addressed reporting subsidies received to support proprietary fund operations. This type of subsidy was not discussed in FASBS 95 since private sector businesses do not have transactions of this type. Nonetheless, the FASB model could still be used in reporting this type of subsidy. Using the FASB model the reporting of these subsidies would be the same as those in issue #3; the payments would be reported in the Operating Activities section. NCGA Statement 1, Governmental Accounting and Financial Reporting Principles, which has been adopted by the GASB, states that proprietary funds were to be used, Ato account for a government=s ongoing organizations and activities that are similar to those often found in the private sector@ (NCGA, 1979, paragraph 26). Further, the Statement identifies two circumstances in which the use of a proprietary fund would be appropriate: ... to account for operations (a) that are financed and operated in a manner similar to private business enterprisesCwhere the intent of the governing body is that the costs ... of providing goods or services to the general public on a continuing basis be financed or recovered primarily through user charges; or (b) where the governing body has decided that periodic determination of revenues earned, expenses incurred, and/or net income is appropriate for capital maintenance, public policy, management control, accountability, or other purposes (NCGA, 1979, paragraph 26). Given the above criteria for proprietary funds in this issue, the GASB evidently did not intend for operating transfers to proprietary funds to be considered part of operations but rather as a nonoperating subsidy. Therefore, support for reporting subsidies as a Noncapital Financing Activity would be consistent with the intent of the GASB. Model Issue #7 This last issue is the defining issue for this section of the analysis and, thus, is the dependent variable for this study. The respondent was to indicate which SCF model was superior overall: the GASB SCF or the FASB SCF. GASB VERSUS FASB: USER PERCEPTIONS 233 This issue was to be used to divide the preceding issues for purposes of analysis. The issue is straightforward. The recipient was asked to select either the GASB model or the FASB model as superior overall, and then to rate the selection using the same scale used in the other evaluations. For this analysis this rating was dropped in order to make the dependent variable dichotomous and allow the use of logit regression analysis. RESEARCH DESIGN The Instrument An envelope, sent to each recipient, contained five separate items. The items included: - a cover letter from the researcher which explained the survey and what was expected from the recipient; - a letter from David R. Bean, the Director of Research for the GASB, encouraging the person to respond to the survey; - a Questionnaire Booklet, consisting of a three-part survey and the Respondent Demographic Data; - one of two Information Booklets used in the survey; and - a postage paid envelope to return the completed survey. The Questionnaire Booklet had three parts. Part I examined the usefulness of cash flow information in assessing the operations of a governmental entity. Part II compared the GASB and FASB models. Part III examined the direct method and indirect method of preparing the SCF. The focus for this study is Part II. The goal for this part of the survey was to answer two research questions: 1. Do the preparers and users recognize and understand the differences between the FASBS 95 and the GASBS 9 SCF models? 2. Do the preparers and users find one model superior to the other? To answer these questions, ten issues were posed to the recipients (see Appendix A). Of these ten, six related specifically to the differences between the FASB and GASB SCF models (Table 1). The respondents= answers to these questions should indicate whether they recognize and understand the differences in the two reporting models and provide some indication of which is perceived as the superior model. 234 SMITH, FREEMAN & BRYAN TABLE 1 Summary of SCF Model Issues. ______________________________________________________________ _ Issue Summary Responses # --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------1 Reporting interest received on investments Reporting debt issued to finance operations. Reporting subsidies paid to other funds. Reporting investments in longterm investments in marketable securities. a b a b a b a 5 Reporting interest paid on debt. 6 Reporting subsidies received from other funds a b a b 2 3 4 b FASBCoperating activity GASBCinvesting activity GASBCnoncapital financing activity FASBCfinancing activity GASBCnoncapital financing activity FASBCoperating activity FASBCinvesting activity (all long-term investments) GASBCinvesting activity restricted to noncapital investments FASBCoperating activity GASBCfinancing activity FASBCoperating activity GASBCnoncapital financing activity ______________________________________________________________ The survey recipients were to respond the issues addressing governmental financial reporting. The Questionnaire Booklet instructed the recipient to examine two SCFs presented in the Information Booklet (shown here in Appendices 2 and 3). All persons received the same SCFs. One SCF was presented using the model required by GASBS 9 while the other was prepared using the FASBS 95 model. The SCF models include government-unique items such as interfund transfers and loans and payments in lieu of taxes to highlight the differences in the two models. Both SCFs used the direct method and included the required reconciliation of operating income (or net income for the FASB model) to net cash provided by operating activities. The purpose of the dual display was to demonstrate how a government enterprise fund would report using each model. Private sector-unique items such as issuing stock or paying dividends were excluded. GASB VERSUS FASB: USER PERCEPTIONS 235 As noted earlier, this part of the survey contained ten pairs of issues for analysis of which six pairs specifically addressed issues related to the two SCF models. Three other issues addressed reporting issues related to the SCF but not restricted to it. The last issue asked the recipient to select the superior SCF model. The scoring system used was: 1 no preference; 2 little preference; 3 moderate preference; and 4 strong preference. When combined with the choice of model for each issue (GASB or FASB), the scoring system results in a seven-point Likert scale where: - 1 indicates a strong preference for the FASB model; - 4 indicates no preference between the models; and - 7 indicates a strong preference for the GASB model. Survey Population There were five groups of recipients in this survey: (1) finance directors from major cities and counties; (2) members of citizen advocacy groups, such as the League of Women Voters; (3) legislative officials from major cities and counties; (4) credit rating agencies and creditors selected from the membership of the National Federation of Municipal Analysts; and (5) independent auditors selected from independent public accounting firms and the fifty state auditor offices. One thousand five hundred surveys were mailed. The surveys were divided equally among the recipient groups identified above. The surveys sent to finance directors and legislators were further divided between city and county officials. Approximately 59 percent of the surveys were sent to city officials and 41 percent were sent to county officials. Table 2 reports the number of surveys sent and the number of responses received from each recipient group. The initial mailing for the survey was sent in June 1993, and contained all of the items identified above. A follow-up mailing was sent to all nonrespondents in early September 1993, containing the same materials as the initial mailing except the cover letter from the GASB. The cover letter 236 SMITH, FREEMAN & BRYAN included in the follow-up mailing mentioned the initial mailing and encouraged the recipients to respond. A follow-up postcard was sent in late September 1993. The postcard alerted or reminded the recipients of the survey and asked them to complete and return it as soon as possible. TABLE 2 Analysis of Surveys Sent, Undeliverable, and Completed ______________________________________________________________ _ Respondent Groups Surveys Undeliverable Adjusted # Responses Mailed Surveys of Surveys Received --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------City Finance Directors 176 4 172 67 City Council Members 176 0 176 23 County Finance Directors 124 1 123 59 County Commissioners 124 3 121 13 NFMA Members 300 10 290 60 Auditors 300 5 295 140 Citizen Groups 300 20 280 63 Totals 1,500 43 1,457 425 ______________________________________________________________ The Response Of the 1,500 surveys sent out, 43 surveys were undeliverable for various reasons, usually because the recipient was no longer at that address or the address was invalid. Of the remaining 1,457 surveys, 425 usable responses were receivedCa response rate of nearly 30 percent. As shown in Table 3, over 87 percent of the 425 usable responses received could be used in this analysis. The problem with most of the unusable responses was that respondents failed to answer all the questions. A few respondents indicated a preference for one statement but did not circle a number to indicate the degree of preference. Even fewer respondents circled the degree of preference without indicating which statement they preferred. Given the systematic nature of the erroneous responses, the analysis excluded all respondents who did not complete the survey correctly. Nonetheless, most of the responses were used. It can be noted immediately that the response groups in Table 3 are different from the recipient groups in Table 2. It was always the intention in GASB VERSUS FASB: USER PERCEPTIONS 237 this survey to combine the city finance directors and the county finance directors into a single analysis group. Combining the city council members and the county commissioners into a single legislator group was planned as well. These groups are shown separately in Table 2 solely to report the distribution of surveys between cities and counties. Further combination of the response groups was not intended. However, as shown in Table 2, the number of responses received from city council TABLE 3 Summary of Responses ______________________________________________________________ _ Respondent Groups Total Responses Responses Used in Received Statistical Analyses ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Finance Directors 126 42.7% 119 94.4% Citizens and Legislators 99 17.2% 74 74.7% Creditors 60 20.7% 49 81.7% Auditors 140 47.5% 128 91.4% Totals 425 29.2% 370 87.1% ______________________________________________________________ _ members and county commissioners was poor. Only 36 of 289 legislators (12.5 percent) responded. Since the numbers were so low, we were concerned that the small sample size could cause analysis problems. Therefore, the decision was made to combine the Legislators group with the Citizens group for analysis purposes. Statistical comparisons revealed no significant differences in the analysis of the Citizens group alone and the combined Citizens and Legislators group. RESEARCH ANALYSIS AND FINDINGS The research analysis in this study involves logit regression analysis. Logit regression is used because the dependent variable is dichotomous (Stone and Rasp, 1991). The dependent variable is a dummy variable with a value of one when a respondent selects the GASB method of reporting cash flows as preferable to the FASB method, as opposed to a value of zero when 238 SMITH, FREEMAN & BRYAN a respondent selects the FASB method of reporting cash flows as preferable to the GASB method. Maddala (1991) states that logit regression analysis is the appropriate procedure where disproportionate sampling from two populations (i.e., those indicating a preference for the GASB method and those indicating a preference for the FASB method) occurs. He notes that, AThe coefficients of the explanatory variables are not affected by the unequal sampling rates from the two groups. It is only the constant term that is affected@ (Maddala, 1991, p. 793). Correcting for the bias in the constant term is only important if the logit analysis is being used to obtain parameter estimates for purposes of developing a predictive model (Palepu, 1986). This study does not develop a predictive model of the choice of the GASB model as opposed to the FASB model, so bias in the constant term has no effect on the analysis and logit regression is appropriate for testing the hypotheses. The following logit regression model is used to test the relationship between preference for the GASB model as opposed to the FASB model and the relative degree of preference for the particular model chosen: CHOICEi = á + â1MI1 + â2MI2 + â3MI3 + â4MI4 + â5MI1 + â6MI7 + åi(1) where: CHOICE = a dummy variable with a value of one when a firm prefers the GASB method of reporting cash flows and a value of zero when a firm prefers the FASB method of reporting cash flows i = respondent 1 though 370 MI1 = the degree of preference for the method chosen based on reporting cash receipts for interest earned on investments MI2 = the degree of preference for the method chosen based on reporting the proceeds from debt issued to finance operating activities MI3 = the degree of preference for the method chosen based on the problem of reporting transfer payments to governmental funds GASB VERSUS FASB: USER PERCEPTIONS 239 MI4 = the degree of preference for the method chosen based on the reporting of cash payments for long-term investments in marketable securities and capital acquisitions MI5 = the degree of preference for the method chosen based on reporting cash paid for interest on debt MI7 = the degree of preference for the method chosen based on reporting subsidies received to support proprietary fund operations å = the residual If the respondents believe the GASB model is superior for reporting the above cash flows, the â values should have positive signs. The values should be negative if the respondents believe the FASB model is superior. Table 4 reports logit regression results for the model. MI2, MI3, and MI5 all show significance at the 0.01 level. Each of these issues shows a preference for the GASB model. In addition, MI4 shows significance at the 0.05 level and a preference for the GASB model. Finally, MI1 is significant only at the 0.1 level, but it demonstrates a surprising preference for the FASB model. Only MI7 did not prove to be statistically significant. These results are analyzed below. TABLE 4 Results of Logit Analysis ______________________________________________________________ _ Variable Coefficient p-value and Significance --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------M11 -0.1766 0.0583* M12 0.2518 0.0002*** M13 0.2746 0.0002*** M14 0.1968 0.0141** M15 0.1839 0.0087*** M17 0.0274 0.7178 ______________________________________________________________ Levels of significance: * 0.10 level ** 0.05 level 240 SMITH, FREEMAN & BRYAN *** 0.01 level The basic argument in this analysis is whether the FASB SCF model is superior (some might say sufficient) for reporting cash flows of government business-type operations or the GASB model is perceived to be a significantly better model. These results would seem to indicate that the differences in the two models are significant and that users and preparers believe the GASB model to be the superior one. In analyzing the results one should not be misled by the differences between the public and private sectors. What is important in these results is that the users and preparers of governmental reports believe that the GASB model is superior to the FASB model for reporting these types of governmental cash flows. Of the three variables significant at the 0.01 level, perhaps the most important is MI5. This issue defines a fundamental difference between the SCF models. As noted in the earlier discussion, the FASB made the decision to include interest payments in the Operating Activities section. Perhaps in response to the widespread criticism by users in the private sector, the GASB reported the cash flows in the financing sections. This variable indicates that users believe the GASB made the correct decision for reporting cash payments for interest on debt. The significance level of MI2 is somewhat less than MI5. Many users of governmental financial reports believe distinguishing between debt issued to support operations and debt issued to finance capital acquisitions is very important. The FASB model does not allow making distinctions between operating debt and capital debt. Thus, the GASB model provides better disclosures in this area for governmental reporting. Finally, the third highly significant variable is MI3. These cash transfers from business-type activities to the governmental funds typically are a means of providing financial support for general government operations. Since this function is not usually the reason for establishing a business-type activity within a government, these transfers should not be reported in the operating section of the SCF. Such reporting would be required in the FASB model, but is avoided in the GASB model through the use of the Noncapital Financing section. There are two surprising findings with MI1. First, it is only moderately significant in the model. Second and even more surprisingly, it has an opposite sign from the other statistically significant issues. Like MI5, this issue marks a fundamental difference in the GASB and FASB SCF models. Recall that in MI5, cash payments for interest are reported as operating cash GASB VERSUS FASB: USER PERCEPTIONS 241 flows in the FASB model but financing cash flows in the GASB model. MI1 represents the flip side of this issue, where cash receipts from interest and dividends are reported as operating cash flows in the FASB model, but are presented as investing cash flows in the GASB model. Also, there was strong opposition at the FASB against reporting cash receipts from interest and dividends in the Operating Activities section. Therefore, it was expected that both MI5 and MI1 would have the same sign and nearly the same level of significance. This difference may be explained by some users and preparers wanting to Aplus up@ the operating cash flows of the business-type activity while not decreasing these cash flows with interest payments (MI5). The result is certainly not consistent with the other findings. The remaining variableCMI7Cwas not statistically significant in the model. This issue represents the opposite side of MI3, and it was expected that it would have the same sign and degree of significance. Although the signs are the same, no conclusions can be drawn given the reported p-value. FINAL ANALYSIS The research questions posed earlier in this paper may now be answered: 1. Do the preparers and users recognize and understand the differences between the FASBS 95 and the GASBS 9 SCF models? The answer to this question must be YES, given the statistical significance of the variables tested above. While MI1 did not have the expected sign and MI7 was not significant, it is apparent that the respondents could distinguish between the two models. 2. Do the preparers and users find one model superior to the other? The answer to this question must be that preparers and users believe the GASB model is superior to the FASB model. This analysis leads one to believe that the GASB was correct in issuing a standard requiring a different format for the SCFCone more suitable for governmental reporting. This result also tends to support the GASB=s decision to continue to use this SCF model as part of the new reporting model currently being proposed. The results also prompt two additional research questions. First, is the GASB model more appropriate than the FASB model for reporting cash flows of private sector not-for-profit organizations (as was discussed when the 242 SMITH, FREEMAN & BRYAN FASB issued Statement No. 117)? Second, would the GASB model be preferred to the FASB model for reporting cash flows for businesses? Only additional research can answer these important questions. When the FASB tested its model, it had only its proposed model and the SCFP to use for comparison purposes. Perhaps the GASB model could prove useful in reporting cash flows in the private sector. NOTES 1. The FASB uses the investing section to report the acquisition and sale of all long-term investments, including both capital assets (property, plant, and equipment) and investments in securities. 2. Quasi-external operating transactions are the result of a transaction made between funds as part of the ordinary course of business for the funds involved. REFERENCES Accounting Principles Board (1963), Opinion No. 3, The Statement of Source and Application of Funds, New York: American Institute of Certified Public Accountants. Accounting Principles Board (1971), Opinion No. 19, Reporting Changes in Financial Position, New York: American Institute of Certified Public Accountants. Financial Accounting Standards Board (1987), Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 95, Statement of Cash Flows, Stamford, CT: Author. Financial Accounting Standards Board (1993), Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 117, Financial Statements of Not-for-Profit Organizations, Stamford, CT: Author. Governmental Accounting Standards Board (1989), Statement No. 9 of the Governmental Accounting Standards Board, Reporting Cash Flows of Proprietary and Nonexpendable Trust Funds and Governmental Entities That Use Proprietary Fund Accounting, Stamford, CT: Author. Maddala, G. S. (1991, October), AA Perspective on the Use of Limited-dependent and Qualitative Variables Models in Accounting Research,@ The Accounting Review, 66: 788-807. GASB VERSUS FASB: USER PERCEPTIONS 243 National Committee on Municipal Accounting (1951), National Committee on Governmental Accounting Bulletin No. 14, Municipal Accounting and Auditing, Chicago: Municipal Finance Officers Association. National Committee on Municipal Accounting (1968), Governmental Accounting, Auditing, and Financial Reporting, Chicago: Municipal Finance Officers Association. National Council on Governmental Accounting (1979), Statement No. 1, Governmental Accounting and Financial Reporting Principles, Chicago: Municipal Finance Officers Association. Palepu, K. (1986, March), APredicting Takeover Targets: A Methodological and Empirical Analysis,@ Journal of Accounting and Economics 8: 3-35. Stone, M., and Rasp, J. (1991, January), ATradeoffs in the Choice Between Logit and OLS for Accounting Choice Studies,@ The Accounting Review, 66, 170-187. 244 SMITH, FREEMAN & BRYAN APPENDIX A Survey Questions PART II Part II of the Information Booklet (pages 4 and 5) contains two Statements of Cash Flows prepared using the requirements of the GASB and the FASB. Please review these two Statements of Cash Flows. The statements are prepared for the same governmental entity. The SCF on page 4 is the GASB format; the statement on page 5 is the FASB format. Government-unique items, such as interfund transfers, are included in these examples to highlight the differences in format. Each issue addressed in this section pertains to the differences in the two SCF formats. In responding to the questions in this section, we are interested in your point of view, not the position of the GASB or the FASB. The following pairs of statements compare the organization and design of the Statement of Cash Flows prepared in accordance with GASB Statement No. 9 and FASB Statement No. 95. We are interested in your opinionCnot the position of the GASB or the FASBCconcerning each of the issues expressed below. For each pair of statements place a check (T) next to the one with which you most agree. Then, indicate how strongly you prefer the statement you chose by circling the corresponding number: (1) no preference, (2) little preference, (3) moderate preference, or (4) strong preference. Circle only one number for the statement selected. Example: _____ a. I would rather watch a college football game. or _____ b. I would rather watch a college basketball game. 1._____ a. I believe that cash receipts for interest earned on investments should be classified as a cash flow from "operating" activities. or _____ b. I believe that cash receipts for interest earned on investments should be classified as a cash flow from "investing" activities. Degree of Preference Strong None 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 GASB VERSUS FASB: USER PERCEPTIONS 245 Appendix A (continued) Survey Questions Part II (continued) 2._____ a. I believe that debt issued to finance operations should be reported in a separate section from debt issued to finance capital acquisitions. or _____ b. I believe that all debt issues should be reported in the same section. 3._____ a. I believe that payments made from an enterprise fund to support the operations of another government activity should be classified as a "noncapital financing" activity for the enterprise fund. or b.I believe that payments made from an enterprise fund to support the operations of another government activity should be classified as an "operating" activity for the enterprise fund. 4._____ a. I believe that cash paid for long-term investments in marketable securities and cash paid for capital acquisitions should be reported in the same section. or _____ b. I believe that cash paid for long-term investments should be reported in a separate section from cash paid for capital acquisitions. 5._____ a. I believe that cash paid for interest on debt should be reported as an "operating" activity. or _____ b. I believe that cash paid for interest on debt should be reported as a "financing" activity. Degree of Preference Strong None 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 246 SMITH, FREEMAN & BRYAN Appendix A (concluded) Survey Questions Part II (continued) 6._____ a. I believe that the reconciliation of net income or operating income to cash flows from operating activities is essential to understanding the SCF. or _____ b. I believe that the reconciliation of net income or operating income to cash flows from operating activities is redundant. 7._____ a. I believe that subsidies received to support the operations of an enterprise fund from other funds should be reported as an "operating" activity. or _____ b. I believe that subsidies received to support the operations of an enterprise fund from other funds should be reported as a "noncapital financing" activity. 8._____ a. I believe governmental fund financial statements should be different from the proprietary funds, including the SCF. or _____ b. I believe governmental fund and proprietary fund financial statements should be the same. 9._____ a. I believe that government enterprises should use the same financia l statements as private sector businesses. or _____ b. I believe that government enterprises should have unique financial statements. 10._____ a. I believe the GASB SCF format is superior overall to the FASB SCF format. or _____ b. I believe the FASB SCF format is superior overall to the GASB SCF format. Degree of Preference Strong None 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 GASB VERSUS FASB: USER PERCEPTIONS 247 APPENDIX B SCF Prepared According to GASB Statement 9 City of Local Government Enterprise Fund Statement of Cash Flows For the Year Ended June 30, 199X Cash Flows from Operating Activities Cash Received from Customers.................................................................. $6,350,000 Other Operating Revenues ..............................................................................120,000 Cash Paid to Employees.............................................................................(3,450,000) Cash Paid to Suppliers for Goods and Services ............................................(2,765,000) Payment in Lieu of Taxes to General Fund .................................................. (250,000) Net Cash Provided (Used) by Operating Activities $ 5,000 Cash Flows from Noncapital Financing Activities Residual Equity Transfer from General Fund ....................................................100,000 Proceeds from Bond Issue ..............................................................................600,000 Repayment of Bonds......................................................................................(50,000) Operating Transfer from Special Revenue Fund................................................. 45,000 Operating Transfer to General Fund................................................................(15,000) Advance from General Fund............................................................................. 10,000 Interest Paid on Bonds ...................................................................................(25,000) Net Cash Provided (Used) by Noncapital Financing Activities...........665,000 Cash Flows from Capital and Related Financing Activities Proceeds from Bond Issue ........................................................................... 1,200,000 Repayment of Bonds.................................................................................... (100,000) Proceeds from Sale of Equipment ..................................................................... 25,000 Acquisition of Capital Assets ........................................................................ (750,000) Residual Equity Transfer from Capital Projects Fund.......................................... 50,000 Interest Paid on Bonds ................................................................................. (100,000) Net Cash Provided (Used) by Capital and Related Financing Activities..........................................................................325,000 Cash Flows from Investing Activities Proceeds from Sale of Investments................................................................... 65,000 Purchase of Investments .............................................................................. (800,000) Interest on Investments ................................................................................. 97,500 Net Cash Provided (Used) by Investing Activities .......................... (637,500) Net Increase (Decrease) in Cash and Cash Equivalents ............................357,500 Cash and Cash Equivalents at the Beginning of the Year ......................... 527,000 Cash and Cash Equivalents at the End of the Year .................................$ 884,500 248 SMITH, FREEMAN & BRYAN APPENDIX B (Continued) Reconciliation of Operating Income to Net Cash Provided by Operating Activities Operating Income......................................................................................... $135,000 Adjustments to reconcile operating income to net cash provided by operating activities Depreciation ....................................................................................... 230,500 Changes in assets and liabilities (Increase) Decrease in Accounts Receivable ..................................(260,000) Increase (Decrease) in Allowance for Doubtful Accounts .....................5,000 (Increase) Decrease in Inventory of Materials and Supplies .............. (13,000) (Increase) Decrease in Prepaid Expenses...........................................10,000 Increase (Decrease) in Vouchers Payable ....................................... (41,500) Increase (Decrease) in Accrued Salaries and Wages Payable ........... (27,000) Increase (Decrease) in Compensated Absences....................................6,000 Increase (Decrease) in Other Accrued Liabilities ........................... (40,000) Net Cash Provided (Used) by Operating Activities ..................................$ 5,000 Noncash investing, capital, and financing activities: In 1992, long-term bonds were exchanged for land, $1,000,000. GASB VERSUS FASB: USER PERCEPTIONS 249 APPENDIX C SCF Prepared According to FASB Statement 95 City of Local Government Enterprise Fund Statement of Cash Flows For the Year Ended June 30, 199X Cash Flows from Operating Activities Cash Received from Customers.................................................................. $6,350,000 Interest on Investments .................................................................................... 97,500 Other Operating Revenues ..............................................................................120,000 Operating Transfer from Special Revenue Fund................................................. 45,000 Cash Paid for Purchases ............................................................................(1,765,000) Cash Paid for Operating Expenses..............................................................(4,450,000) Interest Paid on Bonds ................................................................................. (125,000) Taxes Paid .............................................................................................. (250,000) Operating Transfer to General Fund............................................................ (15,000) Net Cash Provided (Used) by Operating Activities ....................... 7,500 Cash Flows from Investing Activities Proceeds from Sale of Investments................................................................... 65,000 Purchase of Investments .............................................................................. (800,000) Proceeds from Sale of Capital Assets ............................................................... 25,000 Acquisition of Capital Assets ........................................................................ (750,000) Net Cash Provided (Used) by Investing Activities ........................(1,460,000) Cash Flows from Financing Activities Proceeds from Bond Issue ........................................................................... 1,800,000 Repayment of Bonds................................................................................... (150,000) Residual Equity Transfer from General Fund ....................................................100,000 Residual Equity Transfer from Capital Projects Fund.......................................... 50,000 Advance from General Fund......................................................................... 10,000 Net Cash Provided (Used) by Financing Activities.......................... 1,810,000 Net Increase (Decrease) in Cash and Cash Equivalents ............................357,500 Cash and Cash Equivalents at the Beginning of the Year ........................ 527,000 Cash and Cash Equivalents at the End of the Year ................................$ 884,500 250 SMITH, FREEMAN & BRYAN APPENDIX C (Continued Reconciliation of Operating Income to Net Cash Provided by Operating Activities Net Income.................................................................................................... $98,500 Adjustments to reconcile operating income to net cash provided by operating activities Depreciation........................................................................................... 230,500 Gain on Sale of Investments ................................................................... (15,000) Loss on Sale of Capital Assets...................................................................35,000 Changes in assets and liabilities (Increase) Decrease in Accounts Receivable ..................................(260,000) Increase (Decrease) in Allowance for Doubtful Accounts .....................5,000 (Increase) Decrease in Accrued Interest Receivable .............................1,500 (Increase) Decrease in Inventory of Materials and Supplies .............. (13,000) (Increase) Decrease in Prepaid Expenses...........................................10,000 Increase (Decrease) in Vouchers Payable ....................................... (41,500) Increase (Decrease) in Accrued Salaries and Wages Payable ........... (27,000) Increase (Decrease) in Accrued Interest Payable ...............................17,500 Increase (Decrease) in Compensated Absences....................................6,000 Increase (Decrease) in Other Accrued Liabilities ........................... (40,000) Net Cash Provided (Used) by Operating Activities ...............................$ 7,500 Noncash investing and financing activities: Long-term bonds were exchanged for land, $1,000,000.