Who Prefers to Work with Whom? Trait Activation in Classroom Teams

advertisement

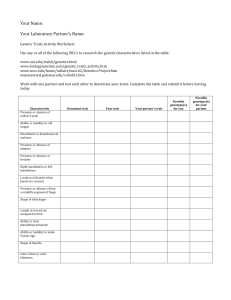

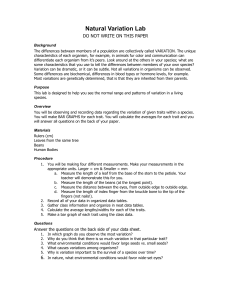

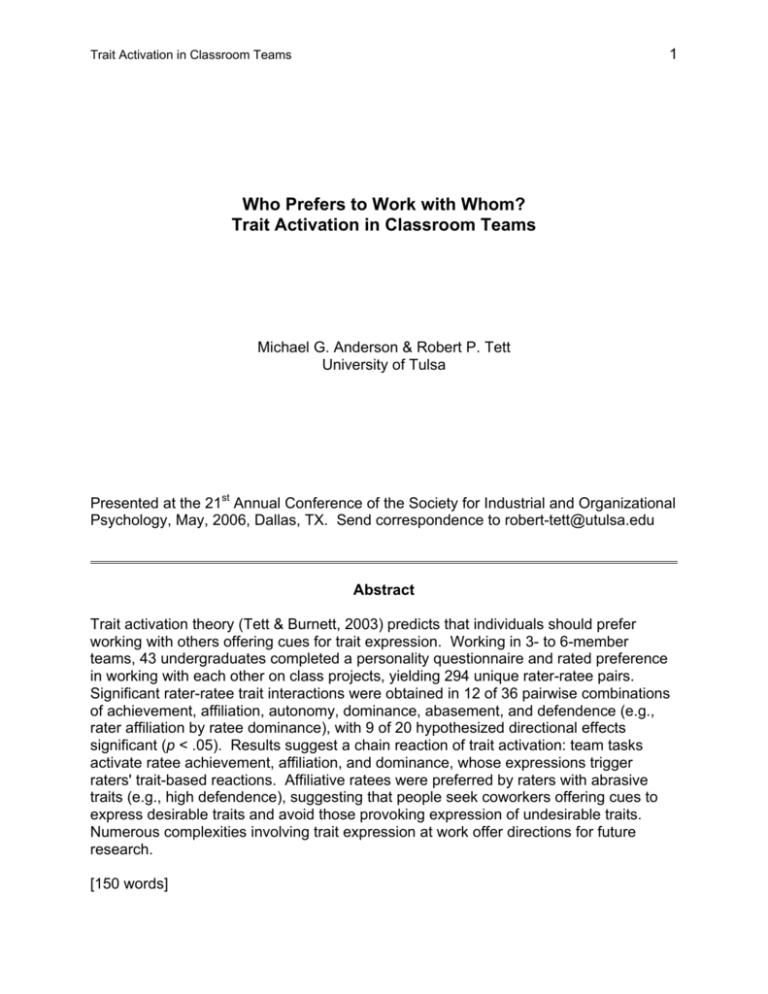

1 Trait Activation in Classroom Teams Who Prefers to Work with Whom? Trait Activation in Classroom Teams Michael G. Anderson & Robert P. Tett University of Tulsa Presented at the 21st Annual Conference of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, May, 2006, Dallas, TX. Send correspondence to robert-tett@utulsa.edu Abstract Trait activation theory (Tett & Burnett, 2003) predicts that individuals should prefer working with others offering cues for trait expression. Working in 3- to 6-member teams, 43 undergraduates completed a personality questionnaire and rated preference in working with each other on class projects, yielding 294 unique rater-ratee pairs. Significant rater-ratee trait interactions were obtained in 12 of 36 pairwise combinations of achievement, affiliation, autonomy, dominance, abasement, and defendence (e.g., rater affiliation by ratee dominance), with 9 of 20 hypothesized directional effects significant (p < .05). Results suggest a chain reaction of trait activation: team tasks activate ratee achievement, affiliation, and dominance, whose expressions trigger raters' trait-based reactions. Affiliative ratees were preferred by raters with abrasive traits (e.g., high defendence), suggesting that people seek coworkers offering cues to express desirable traits and avoid those provoking expression of undesirable traits. Numerous complexities involving trait expression at work offer directions for future research. [150 words] Trait Activation in Classroom Teams 2 Who Prefers to Work With Whom? Trait Activation in Classroom Teams Organizations are increasingly relying on work teams to perform critical operations (Devine, Clayton, Philips, Dunford, & Melner, 1999; Morgan, Salas, & Glickman, 2001), making team building and group dynamics important targets of research. Personality offers one approach to studying interpersonal processes within teams. Team members’ traits (e.g., Extraversion), for example, have been found to influence team outcomes through the task and socioemotional inputs of individual members (Barry & Stewart, 1997). In addition, team composition regarding Conscientiousness, Agreeableness, Extraversion, and Emotional Stability has been reported to influence team performance and viability (Barrick, Stewart, Neubert, & Mount, 1998). Personality is clearly involved in team functioning, but the precise mechanisms are far from clear. Kichuk and Wiesner (1998) identified three ways that personality can contribute to team success: (1) identification of individuals who can work as a part of a team, (2) prediction of team members’ success in particular team roles, and (3) optimization in the compatibility of team members’ personalities. Drawing from trait activation theory (Tett & Burnett, 2003; Tett & Guterman, 2000; Tett & Murphy, 2002), the current study targeted the third, and most ambitious, of these possibilities. Specifically, we sought to clarify how team members’ personality traits interact to influence coworker preference. Personality and Workplace Outcomes Decades of research support linkages between personality and important workplace criteria. Meta-analyses diverse in method and scope converge in their overall support for personality-job performance linkages (e.g., Barrick & Mount, 1991; Hogan & Holland, 2003; Hough, Eaton, & Dunnette, 1990; Huffcutt, Conway, Roth, & Stone, 2001; Tett, Jackson, & Rothstein, 1991; Tett, Jackson, Rothstein, & Reddon, 1999). Meta-analysis has also demonstrated notable relationships between four of the Big Five traits (Neuroticism, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness) and job satisfaction (estimated true correlations = -.29, .25, .17, and .26; respectively). Absenteeism has been reported to be positively related to Extraversion (e.g., Furnham & Miller, 1997; Judge, Martocchio, & Thoresen, 1997) and negatively to Conscientiousness (e.g., Hattrup, O’Connell, & Wingate, 1998; Judge et al., 1997). Collectively, these findings suggest that personality effects on individual-level workplace outcomes are quite broad in scope. Personality is also related to group cohesion (e.g., Barrick et al., 1998; Dryer & Horowitz, 1997; Dyce & O’Connor, 1992; Morse & Caldwell, 1979), which is important because cohesion is positively related to group performance (Evans & Dion, 1991; Mullen & Cooper, 1994), organizational citizenship (Kidwell, Mossholder, & Bennett, 1997), and organizational commitment (Yoon, Ko, & Baker, 1994); and it is negatively related to role uncertainty and absenteeism (Zaccaro, 1991). How personality relates to cohesion, however, has varied. Morse and Caldwell (1979) argued that similarity in personality traits increases individuals’ satisfaction with their work group. Dyce and O’Connor (1992) and Dryer and Horowitz (1997), on the other hand, found that Trait Activation in Classroom Teams 3 personality dissimilarity increased cohesion among coworkers. Observing such complexity within a single study, Barrick et al. (1998) reported that cohesiveness was positively linked to team member similarity on Extraversion but negatively to similarity on Agreeableness. The reasons for such discrepancies are unclear. Moreover, given the diversity of personality traits relevant to work teams, the possibilities for interactions among team members with respect to personality far exceed those considered in simple similarity hypotheses targeting only single traits. The current study was undertaken to assess interpersonal interactions in work groups more broadly, subsuming same-trait as well as different-trait effects. The theoretical framework connecting all our expectations was that of personality trait activation, a topic to which we now turn. A Trait Activation Model of Job Performance Building on classic trait-situation interactionist ideas (e.g., Murray's concept of situational press), Tett and Burnett’s (2003) trait activation model clarifies the mechanisms through which personality is linked to job performance and explains why personality trait measures show situational specificity in predictive validity (e.g., Barrick & Mount, 1991, Tett, et al., 1991; Hough, Ones, & Viswesvaran, 1998). Trait activation holds that personality traits are expressed in response to trait-relevant situational cues (Haaland & Christiansen, 2002; Tett & Guterman, 2000) operating at the task (e.g., dayto-day tasks and duties), social (e.g., coworker expectations, team functions, norms), and organizational (e.g., climate, culture) levels. Job performance is conceived as trait expression that meets work demands at each level. Workers gain intrinsic reward through trait expression per se, and extrinsic reward when trait expressions are valued positively by others. Thus, fit is highest when the work situation (in terms of tasks, coworkers, and the organization as a whole) offers cues for positively valued trait expression. Trait activation theory is compatible with more established models of personenvironment fit. Operating primarily at the task level, Holland's (1985) RIASEC model holds that personality and jobs can be classified into six categories (i.e., Realistic, Investigative, Artistic, Social, Enterprising, and Conventional), and that pairing individuals with appropriate work environments leads to predictable outcomes (e.g., satisfaction, turnover, behavior, performance). Essentially, when individuals’ personalities are properly aligned with the requirements of their work, good things happen. The RIASEC model is perhaps the most widely used model of vocational interests (Holland, 1996), and is supported by a large body of empirical research (Rounds & Tracey, 1993; Tracey & Rounds, 1993). Operating at the organizational level, Schneider’s (1987) attraction-selection-attrition (ASA) model posits that individuals are attracted to, selected by, and remain in organizations with characteristics similar to their own. As with RIASEC, the ASA model has received considerable empirical support (e.g., Bretz, Ash, & Dreher, 1989; Cable & Judge, 1996; Kristof, 1996; Kristoff-Brown, 2000). Trait activation offers a basis for integrating RIASEC and ASA models. RIASEC works because jobs in each category provide opportunities for the expression of specific Trait Activation in Classroom Teams 4 personality traits, such that, when those traits are expressed, job demands are met, yielding high performance, satisfaction, and other positive outcomes. With respect to organizations at the broadest level, ASA works because climates and cultures specific to a given organization offer opportunities for the expression of certain traits. People who have those traits are especially attracted to the organization, are selected into it because expression of the targeted traits is positively valued, and are rejected if valued traits are not expressed. The current investigation targeted trait activation processes operating at the social level, that is, in a team context. More specifically, we tested whether trait activation is related to coworker preference. The main idea here is that one worker’s trait expression offers cues for others to express their traits. If trait expression is intrinsically rewarding, coworkers ought to prefer one another to the degree that each offers opportunities for the other to express his or her traits. Cohesion, in this light, results from mutual trait activation. Below, the distinction between supplementary and complementary fit is reviewed, as well as previous trait activation research, as foundations for testable hypotheses in the current undertaking. Supplementary Versus Complementary Fit Muchinsky and Monohan (1987) identified two types of person-environment congruence. Supplementary fit occurs when individuals “possess characteristics similar to others in the environment” (p. 269), and complementary fit occurs when an individual's traits “complement the characteristics of an environment” (p.271). In terms of trait activation, supplementary fit arises from similarity in personality characteristics and complementary fit arises from dissimilar personality traits that fulfill mutual needs. Personality can thus enhance interpersonal attraction through either or both types of fit. The distinction may help explain why interpersonal attraction has been linked in some cases to personality similarity and in other cases to dissimilarity. The supplementary/complementary distinction is a key part of circumplex models of personality, which, like trait activation theory, hold that individuals have an inherent desire to express their personality traits (Bakan, 1966, Wiggins & Trobst, 1997). In circumplex models, the two most basic drives are for agency (e.g., status, power) and communion (e.g., love, companionship; Bakan, 1966). Interpersonal traits are mapped onto a circle with a horizontal communion axis and a vertical agency axis. Similarity congruency is expected along the communion axis, and complementary congruence along the agency axis (Carson, 1969; Kiesler, 1983). Thus, two people will be compatible if similar on a communion trait, and/or where one is high and the other low on an agentic trait. Research has offered some support for circumplex models, but the mechanisms underlying expectations of supplementary versus complementary compatibility are vague. Trait activation offers a common link. Specifically, in both cases, one person's trait expression offers cues for the other person to express his or her traits. In the case of communion traits, one person's friendliness (e.g., as an expression of affiliation) is an Trait Activation in Classroom Teams 5 invitation for a similar other to respond in kind. In the case of agency traits, one person's dominance, for example, is an invitation for someone low on autonomy to express his or her submissiveness, which, in turn, invites dominance. The principle of mutual trait activation extends beyond circumplex notions, however, encouraging consideration of compatibility involving diverse trait combinations. Results from previous studies of trait activation offer some examples, as discussed below. Previous Trait Activation Research Tett and Guterman (2000) introduced trait activation theory by showing how trait expression as behavioral intentions relates to trait-relevant situational cues. Participants completed a personality inventory and were asked how they would respond to each of 50 scenarios varying in trait-relevance (10 scenarios for each of 5 traits). Results showed that trait-intention correlations were stronger in scenarios judged independently to offer greater opportunity for trait expression. Moreover, crosssituational consistency in intentions was higher when situations were jointly high in traitrelevance. Tett and Murphy (2002) applied trait activation theory to a study of coworker preference based on "paper people." Participants completed a personality inventory and were provided with a set of coworker descriptions in the context of a hypothetical job of research assistant. The coworkers were described as either high or low on 1 of 5 targeted personality traits, and participants judged preference for each coworker in terms of likeability and productivity under assumptions of working together versus apart and with the coworker versus the participant in charge. Overall, results supported the expectation that participants would prefer coworkers who allowed trait expression, and effects were stronger, overall, when participants expected to work closely with their coworkers and when preference targeted likeability versus productivity. Circumplex-based predictions involving both communion and agency were supported. Thus, affiliative participants preferred similar others, and participants low on autonomy preferred dominant coworkers (especially when the latter were in charge). Other findings supported trait activation more broadly. For example, dominant participants avoided defendant coworkers, which, in trait activation terms, may be attributed to the former expecting the latter to not take directions well (thereby constraining expression of dominance). Low-abasement (i.e., arrogant) participants preferred affiliative coworkers because, in trait activation terms, the latter were expected to offer greater acceptance of arrogant expressions. Where defendence falls on the circumplex relative to dominance and where affiliation falls relative to abasement distracts from the more parsimonious idea that people prefer those offering greater opportunity for trait expression. This principle was the primary target of investigation in the current undertaking, building on previous research by examining coworker preference in actual teams. 6 Trait Activation in Classroom Teams Hypotheses Our hypotheses generally follow those proposed in previous research on trait activation, stemming in part from circumplex models. They go beyond the communionbased similarity and agency-based complementarity expectations, however, offering bases for compatibility in terms specific to each combination of traits in keeping with the broader principle of trait activation. Targeted traits were achievement, affiliation, autonomy, dominance, abasement, and defendence. Descriptions of high and low scorers are provided in Table 1. Of the 36 possible interactions, 20 were judged to allow theory-based directional hypotheses. Expectations with brief rationales are offered below, under intra-trait and inter-trait effects. All similarity effects are limited to intra-trait interactions. Some intra-trait interactions, however, may be complementary in that someone high on a given trait may prefer someone low on the same trait (and vice versa). All inter-trait effects are complementary, taking either high-high or high-low forms. Such effects may have multiple causes. For example, a high-low complementary interaction may be driven by (a) raters high on trait A preferring coworkers low on trait B, (b) raters high on trait A seeking to avoid others high on trait B, (c) raters low on trait A preferring others high on trait B, or (d) raters low on trait A seeking to avoid others low on trait B. Our rationales reflect what we consider to be the most plausible bases for the hypothesized interactions. Other rationales may also be viable. Of the 17 inter-trait hypotheses, 12 are 6 pairs of reciprocal expectations (e.g., high Trait A prefers low Trait B, and low Trait B prefers high Trait A). Such cases are identified to allow direct comparison of rationales. Finally, several hypotheses (i.e., 4, 8, 19, and 20) identify a special role for affiliation in teamwork. Affiliative individuals prefer teamwork and are motivated to promote team viability (i.e., the ability to work together again in the future; Barrick et al., 1998). One mechanism by which this may play out is that affiliative individuals, because of their desire to establish and maintain social relationships, are more tolerant of abrasive trait expression by others. Of the 6 traits under consideration here, one end of each of 4 may be seen by others as abrasive: high achievement ("task master"), high dominance, low abasement (i.e., arrogance), and high defendence. Individuals with such traits are expected to prefer affiliative coworkers. Intra-trait Hypotheses 1. Raters high on affiliation should prefer similar others because expressing affiliation offers cues for other affiliative group members to respond in kind (similarity). 2. Raters high on autonomy should prefer similar others, as those who value their independence will appreciate those who allow them to work independently (similarity). Trait Activation in Classroom Teams 3. 7 Raters high on dominance should prefer others low on dominance, as those seeking to lead should find it easier to do so among others lacking that aspiration (high-low complementarity). Reciprocal (Paired) Inter-trait Hypotheses Achievement-Affiliation 4. Raters high on achievement should prefer affiliative coworkers, as the greater involvement of the latter in group engagements increases opportunities to express achievement (high-high complementarity). In addition, because achievement strivers can be seen as “task masters,” they may especially appreciate the acceptance offered by affiliative group members. 5. Raters high on affiliation should prefer others high on achievement because the latter will be especially engaged in the task, thereby increasing opportunity for the expression of affiliation (high-high complementarity). Autonomy-Affiliation 6. Raters low on autonomy should prefer coworkers high on affiliation, as seeking guidance and support will be welcomed more by affiliative than by non-affiliative group members (high-low complementarity). 7. Raters high on affiliation should prefer coworkers low on autonomy, as those seeking guidance and support offer greater opportunity to be affiliative (high-low complementarity). Dominance-Affiliation 8. Raters high on dominance should prefer others high on affiliation, as expressing affiliation in group engagements increases opportunities to express dominance (high-high complementarity). In addition, because dominant individuals can be seen as domineering, they may especially appreciate the acceptance offered by affiliative group members. 9. Raters high on affiliation should prefer others high on dominance, as expressing dominance in group engagements increases opportunities to express affiliation (high-high complementarity). Autonomy-Dominance 10. Raters high on autonomy should seek to avoid those high on dominance because the latter will seek to impose directions incompatible with a sense of independence in task completion (high-low complementarity). Trait Activation in Classroom Teams 8 11. Raters high on dominance should prefer those low on autonomy because the latter will more willingly accept direction (high-low complementarity). Achievement-Defendence 12. Raters high on achievement should seek to avoid those high on defendence because defensive reactions can dampen the climate for achievement initiatives (high-low complementarity). 13. Raters high on defendence should seek to avoid those high on achievement because the latter are likely to have low tolerance for defensiveness, reducing opportunity to express defendence (high-low complementarity). Dominance-Defendence 14. Raters high on dominance should seek to avoid those high on defendence because the latter are likely to react negatively to direction, dampening the climate for dominance expression (high-low complementarity). 15. Raters high on defendence should seek to avoid those high on dominance because the latter are likely to have low tolerance for defensiveness, reducing opportunity to express defendence (high-low complementarity). Non-reciprocal (Unpaired) Inter-trait Hypotheses 16. Raters high on autonomy should prefer others high on achievement because task focus, as an expression of achievement striving, clarifies what autonomous individuals can be autonomous about (high-high complementarity). 17. Raters high on abasement should prefer coworkers high on achievement because task focus, as an expression of achievement striving, enhances opportunities to express humility (e.g., due to perceived unmet objectives; high-high complementarity). 18. Raters high on abasement should prefer coworkers high on dominance because receiving directions from dominant others offers greater opportunity to express humility (high-high complementarity). 19. Raters low on abasement (i.e., arrogant raters) should prefer coworkers high on affiliation because the former will especially appreciate the acceptance offered by affiliative group members (high-low complementarity). 20. Raters high on defendence should prefer coworkers high on affiliation because the former will especially appreciate the acceptance offered by affiliative group members (high-high complementarity). 9 Trait Activation in Classroom Teams Method College students enrolled in two introductory I/O psychology classes (in different years) completed the Personality Research Form (PRF; Jackson, 1989) and were randomly assigned during the semester to 3 different groups, each with 3 to 6 members such that no student had the same coworker in more than one group. Each group collaborated on 3 to 5 team exercises, at least one of which required meetings in and out of class. For example, in one exercise, each group developed a behaviorally anchored rating scale for the job of police officer using critical incidents derived from watching TV cop shows. Group and individual performance did not contribute to course grades, but groups shared the products of their efforts in class for pedagogical purposes. At the end of each group's tenure, participants rated one another on coworker preference using an 18-item scale (alpha = .96). Sample items include, "I enjoyed working with this person on the team tasks" and "In general, I would like to work with this person in a real job." In all, 43 raters judged 4 to 12 different team members, generating 332 unique rater-ratee pairs. Cases were dropped if PRF Infrequency scores exceeded 3, suggesting nonpurposeful responding, and if raters failed to distinguish among ratees on coworker preference within a given group. Useable N was 294 rater-ratee pairs. In order to control for rater differences in leniency/severity on the preferences measure, ratings were standardized per item within raters. Thus, for a rater with 9 ratees (e,g, 3 in each of 3 4-member groups), the mean and standard deviation across those 9 ratees on a given item were calculated for that rater as a basis for converting each raw rating into a rater-specific standard score. The result is that all transformed item ratings capture variance across ratees within raters, centered on a value of 0. The total score per rater-ratee pair was taken as the mean of the 18 standardized preference items. Although our primary focus was interactions between rater and ratee traits, we also assessed corresponding main effects. Correlations between ratee traits and preference ratings would address whether certain traits in coworkers are more desirable than others. One might expect, for example, that affiliative ratees would be judged more favorably. To assess ratee main effects, we averaged the standardized preference ratings within ratees over all raters who judged a given ratee. N for these correlations was 43 ratees. (Correlations using means of raw preference ratings were similar to those obtained using mean standard scores and are not reported here.) Correlations between rater traits and preference ratings would speak to whether rater personality influences the rating process independently of ratees' traits. To assess rater main effects, we averaged preference ratings within raters over all ratees judged by the given rater, based on raw scores to allow rater differences to emerge. N for these correlations was 37 raters. 10 Trait Activation in Classroom Teams Interactions were assessed using rater-ratee pairs (N = 294) by regressing raters’ coworker preferences onto rater and ratee personality (step 1) and their products (step 2, after centering on the basis of standard scores) in 36 analyses formed by pairing all 6 traits to each other (e.g., rater Abasement by ratee Dominance, rater Dominance by ratee Abasement). Significant interactions were interpreted by examining plots of (standardized) preference total score means based on participants scoring in the upper and lower thirds of the sample on each trait involved in the given interaction (N range = 25 to 71). Results Main effect correlations for both ratees and raters are reported in Table 2. Notably, none of the 6 correlations involving ratee traits is significant, suggesting that coworker preference is not strongly tied solely to particular ratee traits in this sample. Three of the 6 correlations involving rater traits, however, are significant. Results suggest that raters high on affiliation, high on abasement, or low on defendence were more lenient in judging coworker preference than those at the opposite ends of those dimensions. Changes in R square with the addition of the rater-trait-by-ratee-trait interaction term are shown in Table 3. Significant effects are evident in 12 of the 36 cases (33%). Of the 20 hypothesized effects, 10 (50%) are significant, with all but one operating in the expected direction. The exception, rater-Dominance-by-ratee-Dominance (H3), supported a high-high similarity interaction rather than the expected high-low complementarity. Notably, this is the only significant similarity effect observed out of the 6 possibilities. Of the 6 pairs of reciprocal hypotheses, only the Dominance-Affiliation pair was supported in both cases, such that dominant raters preferred affiliative coworkers (H8) and vice versa (H9). For the remaining 5 pairs of reciprocal hypotheses, 2 received support for one half of the pair: affiliative raters preferred high achievement coworkers (H5) and defendant raters avoided them (H13), but the reverse was not supported significantly in either case (H4 and H12, respectively). All 5 of the non-reciprocal hypotheses were supported, such that autonomous raters preferred high achievement coworkers (H16), low abasement (i.e., arrogant) raters avoided high achievement coworkers (H17), high abasement raters preferred dominant coworkers (H18), and both low abasement (i.e., arrogant) and high defendant raters preferred affiliative coworkers (H19 and H20, respectively). Both remaining significant interactions were unexpected (2 of 16 = 12.5%): nonautonomous raters preferred high abasement coworkers and non-affiliative raters avoided defendant coworkers. The latter reciprocates the hypothesized rater defendence by ratee affiliation interaction, adding to the significant expected dominance-affiliation reciprocation. Significant hypothesized interactions are depicted in Figures 1, 2, and 3, respectively, for ratee achievement, ratee affiliation, and ratee dominance. 11 Trait Activation in Classroom Teams Discussion Our goal was to assess whether coworker preference in student teams can be explained in terms of personality trait activation. Results were mixed, with under half of the expected interactions statistically significant, and significant effects yielding overall modest effect sizes (range = 1% to 3% unique variance explained). Of the 6 pairs of expected reciprocal effects, only 1 (high DOM-high AFF) was supported both ways. An additional reciprocation emerged for the AFF-DEF combination, only one direction of which was expected (H20: rater high DEF-ratee high AFF). Reciprocated preferences seem ideal for cohesion, and current results thus support such effects for 2 of the 6 traits. Interpersonal attraction working in just one direction may be beneficial nonetheless, and 4 of the 5 predicted non-reciprocal effects (H16 to H19) were supported. The meager support for reciprocal effects led us to examine the pattern of results differently. Notably, 10 of the 12 significant interactions involve just 3 of the 6 ratee traits: achievement, affiliation, and dominance. High achievement ratees were preferred by affiliative, autonomous, high abasement, and low defendant raters (see Figure 1), affiliative ratees were preferred by dominant, low abasement, and high defendant raters (Figure 2), and dominant ratees were preferred by affiliative, dominant, and high abasement raters (Figure 3). The predominance of these 3 ratee traits may be tied to the nature of the tasks, with achievement activated by task demands, and affiliation and dominance by the social nature of the tasks. The interactions reveal trait-based rater reactions to ratee trait expressions, suggesting a chain reaction of trait activation effects: team tasks activate traits directly related to such tasks (achievement, affiliation, dominance), and then raters, as a function of their own traits, react to ratees’ responses to team-task cues, as expressed in differential coworker preference. That some traits are activated directly by the team tasks and other traits by team members’ trait expressions is consistent with trait activation theory’s separation of cues at the task and social levels (Tett & Burnett, 2003), and shows how the theory can help model the complexities of person-job fit based on personality traits. Further research into which traits interact under which conditions relating to tasks, norms, and group composition, we believe, will facilitate personality-oriented team building, leading to better management of team cohesion and performance. Interestingly, rater achievement was involved in none of the significant rater-ratee interactions (see ACH column results in Table 3). This may be due in part to achievement being a task-related variable and, accordingly, less sensitive to the effects of coworkers' traits. Our results are somewhat surprising, nonetheless, as others' traits were expected to affect achievement expression (e.g., as per H4 and H12). One possible explanation is that task objectives and methods in the current study were clear enough to negate coworker trait effects. Rater achievement might be more likely to interact with ratee traits if conditions for success are more ambiguous, creating opportunity for conflict regarding goals and paths. Further research is needed to assess the conditions under which achievement expression is affected by coworker traits. Trait Activation in Classroom Teams 12 Our results also revealed no significant interactions involving ratee autonomy (see upper middle row of Table 3). Thus, in terms of trait activation, ratee autonomy did not affect expression of targeted coworker traits. This was unexpected, especially in the case of rater dominance (H11), which previous research, in keeping with circumplexbased expectations, has been found to interact with autonomy (e.g., Tett & Murphy). A possible reason for the noted null results is that the tasks in the current undertaking were unstructured with respect to authority, creating no obvious demand for leadership or followership. Ratee autonomy may be more likely to affect expression of rater's traits — especially dominance — when command hierarchies are more salient, for example, by assignment of leader and follower roles. Special Roles for Affiliation in Team Work We reasoned that affiliative group members would be preferred by members with abrasive traits identified here as high achievement (i.e., "task master"), high dominance (i.e., domineering), low abasement (i.e., arrogance), and high defendence (i.e., defensiveness). Three of the 4 hypothesized cases were significant: raters high on dominance (H8), low on abasement (H19), and/or high on defendence (H20) especially preferred affiliative coworkers. The interaction involving rater achievement (H4) was not significant, but the expected pattern was clearly evident in the plot of preference means for that effect. Our results are consistent with previous research showing that group member affiliation contributes to group cohesion (Barrick et al., 1998; van Vianen & De Dreu, 2001). In terms of trait activation, one reason for this may be that affiliative members tolerate abrasive trait expression, accepting members with such traits for who they are. A second possibility, not raised earlier, is that affiliative behavior deactivates abrasive traits. These two rationales are not mutually exclusive, and both fall within a refined trait activation framework. The first explanation (i.e., acceptance of abrasive reactions) bears on extrinsic motivation, deriving from the value others place on one’s trait expressions. The second (i.e., deactivation) bears more on trait activation per se, but calls for refinement of the underlying principle, one that takes into account the desirability of the given trait. Greater opportunity for trait expression should be appreciated when the trait is desirable. For traits whose expression the individual finds undesirable (perhaps from the negative reactions of others in past experience), greater appreciation may be given to those who limit provocation of such negative traits (e.g., by being friendly). Current results offer no basis for distinguishing between these two mechanisms, calling for more detailed investigation into why affiliative coworkers are especially preferred by those with abrasive traits. Untold Complexities Trait activation offers a parsimonious basis for understanding both supplementary and complementary fit among team members and for integrating fit at the social level, task level (e.g., RIASEC), and organizational level (e.g., ASA). The broad scope of trait Trait Activation in Classroom Teams 13 activation belies complexities that challenge the predictability of personality-based person-job fit. One such complexity, noted above, is that traits activated at the task level may differ from those activated at the social level. We suggest in the current study, for example, that achievement-related responses to the tasks became fodder for positive reactions by autonomous team members because, as per the rationale in H16, achievement behaviors clarify what team members can be autonomous about. Thus, trait activation operating at the social level can be driven by task features, and predictions of trait-based coworker preference need to take account of factors operating at both levels (i.e., in terms of interactions among rater traits, ratee traits, and task variables, e.g., who is in charge; Tett & Murphy, 2002). A second set of complexities arises from consideration of interactions among traits within individuals. For example, the way others react to a dominant team member will likely depend on whether that member’s dominance is combined with high versus low emotional stability, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and open-mindedness. Stronger interactions among team members leading to differential coworker preference may be evident using personality profiles. Current results, offering modest support for the effects of individual trait activation, likely underestimate the impact of personality trait configurations on coworker preference. Following from the previous point, current results suggest that coworker preference need not rely on mutual trait activation. Preference was a two-way street for dominance-affiliation, defendence-affiliation, and dominance-dominance, but 7 of 12 significant interactions were non-reciprocal. This raises the interesting question of whether interpersonal compatibility (or incompatibility) can result from one-way trait activation involving different pairs of traits. For example, person A, who is high on defendence and high on dominance might be compatible with person B, who is low on achievement and high on abasement because the high rater DEF-low ratee ACH complementarity will lead A to prefer B, and the high rater ABA-high ratee DOM complementarity will lead B to prefer A. Such possibilities may be managed in part using personality profiles, as discussed above, but they may require consideration at the level of specific traits. A fourth complexity stems from the observation that team cohesion is not strongly tied to team performance. Evans and Dion (1991) reported a corrected meta-analytic mean correlation of just .42, suggesting that there may be an optimal level of cohesion beyond which performance suffers. Those seeking to take personality into account when building teams need to consider that connecting personality to performance requires both trait activation and evaluation of trait-expressive behaviors (Tett & Burnett, 2003). Finding people who prefer one another in team settings may or may not be productive. Looking at it the other way around, more productive teams may be composed of members who are not entirely mutually preferred. Identifying the conditions under which high versus moderate (and perhaps even low) cohesion yields the best team performance is an important target for future research. Trait Activation in Classroom Teams 14 Further complexities challenging personality-based predictions in teams can be expected from a variety of other sources, including team size, team member roles and their interdependence, group norms, individuals’ unique skills and abilities (and the lack thereof), and organizational culture. Personality operates in such a rich nexus of factors that sorting out all the important main and interaction effects can be expected to occupy researchers' attention for some time to come. No one approach is likely to account for all the noted complexities, and trait activation theory is no exception. However, that people are motivated to express positively valued traits and, hence, to seek situations where they can express those traits and be accepted for who they are offers a parsimonious framework for addressing the noted complexities toward making better use of personality data in the workplace. Summary and Conclusions 1. Of 20 hypothesized directional interactions between rater and ratee traits, 9 were significant (45%), effects ranging from 1% to 3% explained variance in coworker preference. Two pairs of reciprocal complementarity effects were observed, one of which was unpredicted. Significant results are consistent, nonetheless, with trait activation principles. 2. That 10 of the 12 significant interactions involved just 3 of the 6 ratee traits relevant to the team tasks suggests a chain reaction of trait activation effects: the tasks activated achievement, affiliation, and dominance, then raters reacted to those trait expressions based on their own traits. Research on personality-based coworker preference needs to account for trait activation operating at both the task and social levels. 3. Affiliative team members were preferred by those with abrasive traits of high dominance, high defendence, and low abasement (high achievement yielded a similar but non-significant pattern). Whether ratee affiliation confers acceptance or deactivation of abrasive trait expression (or both) is a matter for further inquiry. 4. Trait activation theory warrants refinement by taking account of trait desirability. Specifically, individuals can be expected to seek conditions offering cues to express desirable traits and avoid those offering cues to express undesirable traits. 5. Personality operates in a veritable sea of potential moderators. Current findings encourage further research into associated complexities using trait activation theory as a relatively parsimonious integrative framework. 15 Trait Activation in Classroom Teams References Bakan, D. (1966). The duality of human existence: Isolation and communion in Western man. Boston: Beacon. Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1991). The big five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 44, 1-26. Barrick, M. R., Stewart, G. L., Neubert, M. J., & Mount, M. K. (1998). Relating member ability and personality to work-team processes and team effectiveness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 377-391. Barry, B., & Stewart, G. L. (1997). Composition, process, and performance in selfmanaged groups: The role of personality. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 6278. Bretz, R. D., Jr., Ash, R. A., & Dreher, G. F. (1989). Do people make the place? An examination of the attraction-selection-attrition hypothesis. Personnel Psychology, 42, 561-581. Cable, D. M., & Judge, T. A. (1996). Person-organization fit, job choice decisions, and organizational entry. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 67, 294-311. Carson, R. C. (1969). Interaction Concepts of Personality. Chicago: Aldine. Devine, D. J., Clayton, L. D., Philips, J. L., Dunford, B. B., & Melner, S. B. (1999). Teams in organizations: Prevalence, characteristics, and effectiveness. Small Group Research, 30, 687-711. Dryer, D. C., & Horowitz, L. M. (1997). When do opposites attract? Interpersonal complementarity versus similarity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72(3), 592-603. Dyce, J., & O’Conner, B. P. (1992). Personality complementarity as a determinant of cohesion in bar bands. Small Group Research, 23(2), 185-198. Evans, C. R., & Dion, K. L. (1991). Group cohesion and performance: A meta-analysis. Small Group Research, 22(2), 175-186. Furnham, A., & Miller, T. (1997). Personality, absenteeism and productivity. Personality and Individual Differences, 23(4), 705-707. Haaland, S., & Christiansen, N. D. (2002). Implications of trait-activation theory for evaluating the construct validity of assessment center ratings. Personnel Psychology, 55, 137-163. Hattrup, K., O’Connell, M. S., & Wingate, P. H. (1998). Prediction of multidimensional criteria: Distinguishing task and contextual performance. Human Performance, 11(4), 305-319. Hogan, J. & Holland, B. (2003). Using theory to evaluate personality and jobperformance relations: A socioanalytic perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 100-112. Trait Activation in Classroom Teams 16 Holland, J. L. (1985). Making vocational choices: A theory of vocational personalities and work environments (2nd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Holland, J. L. (1996). Exploring careers with a typology, American Psychologist, 51, 397406. Hough, L. M., Eaton, N. K., & Dunnette, M. D. (1990). Criterion-related validities of personality constructs and the effect of response distortion on those validities. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75, 581-595. Huffcutt, A. I., Conway, J. M., Roth, P. L., & Stone, N. J. (2001). Identification and metaanalytic assessment of psychological constructs measured in employment interviews. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 897-913. Jackson, D. N., (1989). Personality Research Form manual. Port Huron, MI: Sigma Assessment Systems. Kichuk, S. L., & Wiesner, W. H. (1998). Work team: Selecting members for optimal performance. Canadian Psychology, 39, 23-32. Kidwell, R. E., Jr., Mossholder, K. W., & Bennett, N. (1997). Cohesiveness and organizational citizenship behavior: A multilevel analysis using work groups and individuals. Journal of Management, 23(6), 775-793. Kiesler, D. J. (1983). The 1982 interpersonal circle: A taxonomy for complementarity in human transactions. Psychological Review, 90, 185-214. Kristof, A. L. (1996). Person-organization fit: An integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurement, and implications. Personnel Psychology, 49, 149. Kristof-Brown, A. L. (2000). Perceived applicant fit: Distinguishing between recruiters’ perceptions of person-job and person-organization fit. Personnel Psychology, 53, 643-671. Hough, L. M., Ones, D. S., & Viswesvaran, C. (1998, April). Personality correlates of managerial performance constructs. Paper presented in R. C. Page (Chair) Personality Determinants of Managerial Potential Performance, Progression and Ascendancy. Symposium conducted at the 13th annual conference of the Society for Industrial Organizational Psychology, Dallas. Jackson, D. N. (1989). Personality Research Form manual. Port Huron, MI: Sigma Assessment Systems. Judge, T. A., Martocchio, J. J., & Thoresen, C. J. (1997). Five-Factor Model of personality and employee abuse. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 745-755. Morgan, B. B., Jr., Salas, E., & Glickman, A. S. (2001). An analysis of team evolution and maturation. The Journal of General Psychology, 120, 277-291. Morse, J. J., & Caldwell, D. F. (1979). Effects of personality and perception of the environment on satisfaction with task group. The Journal of Psychology, 103, 183192. Trait Activation in Classroom Teams 17 Muchinsky, P.M., & Monahan, C.J. (1987). What is person-environment congruence? Supplementary versus complementary models of fit. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 31, 268-277. Mullen, B., & Cooper, C. (1994). The relation between group cohesiveness and performance: An integration. Psychological Bulletin, 115(2), 210-227. Rounds, J., & Tracey, T. J. (1993). Prediger’s dimensional representation of Holland’s circumplex. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 875-890. Schneider, B. (1987). The people make the place. Personnel Psychology, 40, 437-453. Tett, R. P., & Burnett, D. D. (2003). A personality trait-based interactionist model of job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 500-517. Tett, R. P., & Guterman, H. A. (2000). Situation trait relevance, trait expression, and cross-situational consistency: Testing a principle of trait activation. Journal of Research in Personality, 34, 397-423. Tett, R. P., Jackson, D. N., & Rothstein, M. (1991). Personality measures as predictors of job performance: A meta-analytic review. Personnel Psychology, 44, 703-742. Tett, R. P., Jackson, D. N., Rothstein, M., & Reddon, J. R. (1999). Meta-analysis of bidirectional relations in personality-job performance research, Human Performance, 12, 1-29. Tett, R. P., & Murphy, P. J. (2002). Personality and situations in coworker preference: Similarity and complementary in worker compatibility. Journal of Business and Psychology, 17, 223-241. Tracey, T. J., & Rounds, J. (1993). Evaluating Holland’s and Gati’s vocational-interest models: A structural meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 113, 229-246. van Vianen, A. E. M., & De Dreu, C. K. W. (2001). Personality in teams: Its relationship to social cohesion, task cohesion, and team performance. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 10, 97-120. Wiggins, J. S., & Trobst, K. K. (1997). When is a circumplex an “interpersonal circumplex”? The case of supportive actions. In R. Plutchik & H. R. Conte (Eds.), Circumplex models of personality and emotions (pp. 57-80). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Yoon, J., Ko, J., & Baker, M. R. (1994). Interpersonal attachment and organizational commitment: Subgroup hypothesis revisited. Human Relations, 47(3), 329-351. Zaccaro, S. J. (1991). Nonequivalent associations between forms of cohesiveness and group-related outcomes: Evidence for multidimensionality. Journal of Social Psychology, 131(3), 387-399. 18 Trait Activation in Classroom Teams Table 1 Descriptions of High and Low Scorers on Six Targeted Personality Traits. Trait Description of High Scorers Description of Low Scorers Achievement Aspires to accomplish difficult tasks; maintains high standards and is willing to work toward distant goals; responds positively to competition; willing to put forth effort to attain excellence. Tends not to set ambitious goals; prefers easy work over difficult challenges; doers not strive for excellence; may respond negatively to challenges and competition; overestimates or exaggerates obstacles. Affiliation Enjoys being with friends and people in general; accepts people readily; makes efforts to win friendships and maintain association with people. Satisfied being alone; does not actively seek out the company of others; has little urge to meet new people; does not initiate conversations; keeps people at an armÕs length. Autonomy Tries to break away from restraints, confinement, or restrictions of any kind; enjoys being unattached, free, and not tied to people, places, or obligations; may be rebellious when faced with restraints. Willingly accepts social obligations and attachments; prefers to follow rules imposed by people or by custom; listens to the advice and opinions of others, including superiors and leaders; is amenable to being easily led or influenced; is reliant on others for direction. Dominance Attempts to control environment, and to influence or direct other people; expresses opinions forcefully; enjoys the role of leader and may assume it spontaneously. Avoids positions of power, authority, and leadership; does not like to direct other people; prefers not to impose own opinions on others; rarely expresses opinions other than to agree. Abasement Shows a high degree of humility; accepts slams and criticisms even when not deserved; willing to accept an inferior position; tends to be selfeffacing. Refuses to take blame for others' mistakes; has a high self-opinion; does not experience guilt easily; does not allow others to take advantage of his or her good will; asserts own rights; avoids apologizing. Defendence Ready to defend self against real or imagined harm from other people; takes offense easily; does not accept criticism readily. Is willing to concede mistakes; willingly changes own opinions; is not angered or upset by criticism; is vulnerable to attack or question; is not easily offended; has "nothing to hide." Source: Personality Research Form Manual (Jackson, 1989). 19 Trait Activation in Classroom Teams Table 2 Correlations Between Coworker Preference and Ratee and Rater Trait Scores. Trait Rateea (N = 43) Raterb (N = 37) .00 .06 -.02 .11 -.07 -.15 -.04 .40 * .27 -.12 .36 * -.32 * Achievement Affiliation Autonomy Dominance Abasement Defendence a based on mean standardized coworker preference scores based on mean raw coworker preference scores *p<.05, two-tailed b Table 3 R2 Change for Rater-by-Ratee Trait Interactions in Predicting Mean Standardized Coworker Preference (N = 294 pairs). Rater trait Ratee trait ACH AFF AUT DOM ABA DEF Achievement Affiliation Autonomy Dominance Abasement Defendence .005 .005 .000 .004 .003 .005 .013 * .004 .000 .033 *** .004 .012 * .017 ** .001 .003 .002 .011 * .005 .005 .009 * .000 .009 * .002 .003 .021 *** .022 *** .002 .010 * .004 .003 .013 ** .026 *** .001 .006 .004 .000 *p < .05, **p < .025, ***p < .01, one-tailed 20 Trait Activation in Classroom Teams Figure 1 Rater-Ratee Trait Interactions Involving Ratee Achievement (ACH) .3 .2 .1 .0 -.1 -.2 -.3 High ACH Low ACH .3 .2 .1 .0 -.1 -.2 -.3 Low High Rater Affiliation .3 .2 .1 .0 -.1 -.2 -.3 Low ACH High ACH Low High Rater Defendence Low ACH High ACH Low High Rater Autonomy .3 .2 .1 .0 -.1 -.2 -.3 High ACH Low ACH Low High Rater Abasement 21 Trait Activation in Classroom Teams Figure 2 Rater-Ratee Trait Interactions Involving Ratee Affiliation (AFF) .3 .2 .1 .0 -.1 -.2 -.3 High AFF Low AFF .3 .2 .1 .0 -.1 -.2 -.3 Low High Rater Dominance Low AFF High AFF Low High Rater Abasement .3 .2 .1 .0 -.1 -.2 -.3 High AFF Low AFF Low Rater High 22 Trait Activation in Classroom Teams Figure 3 Rater-Ratee Trait Interactions Involving Ratee Dominance (DOM) .3 .2 .1 .0 -.1 -.2 -.3 High DOM Low DOM .3 .2 .1 .0 -.1 -.2 -.3 High DOM Low DOM Low High Rater Affiliation Low High Rater Dominance .3 .2 .1 .0 -.1 -.2 -.3 High DOM Low DOM Low High Rater Abasement