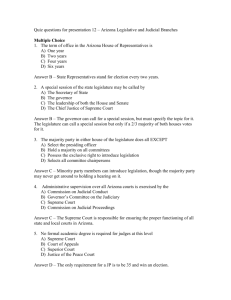

The Arizona Legislature

advertisement

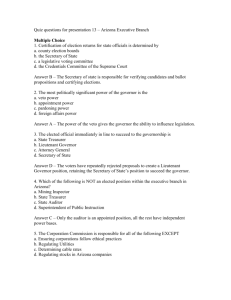

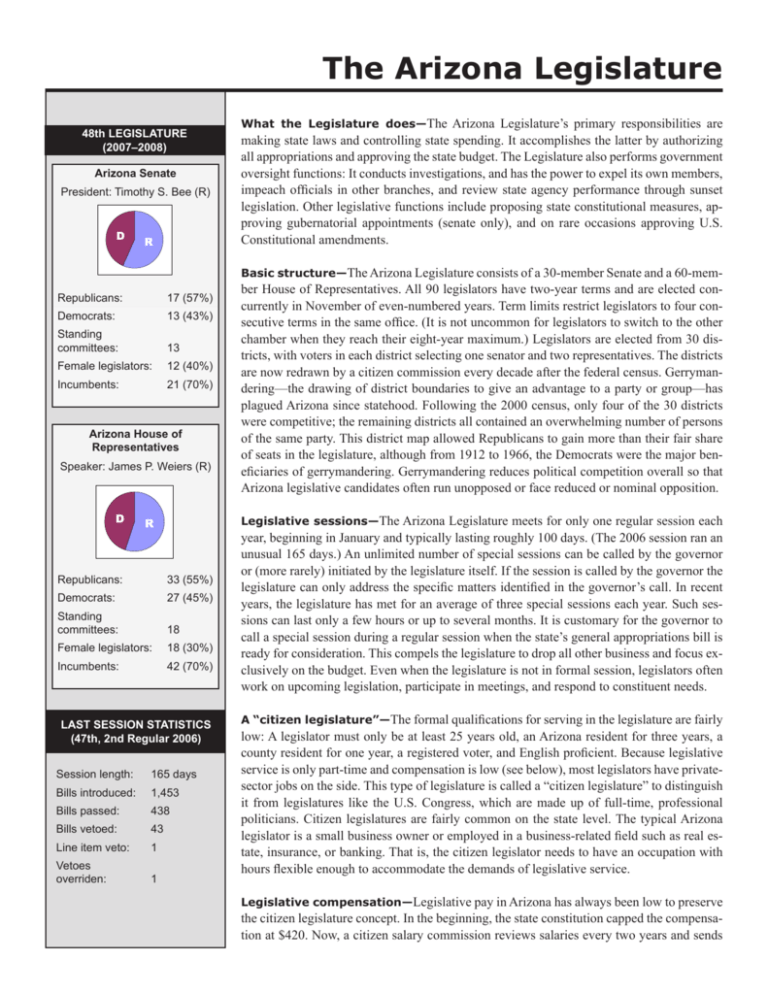

The Arizona Legislature 48th LEGISLATURE (2007–2008) Arizona Senate President: Timothy S. Bee (R) D R What the Legislature does—The Arizona Legislature’s primary responsibilities are making state laws and controlling state spending. It accomplishes the latter by authorizing all appropriations and approving the state budget. The Legislature also performs government oversight functions: It conducts investigations, and has the power to expel its own members, impeach officials in other branches, and review state agency performance through sunset legislation. Other legislative functions include proposing state constitutional measures, approving gubernatorial appointments (senate only), and on rare occasions approving U.S. Constitutional amendments. Basic structure—The Arizona Legislature consists of a 30-member Senate and a 60-mem- Republicans: 17 (57%) Democrats: 13 (43%) Standing committees: 13 Female legislators: 12 (40%) Incumbents: 21 (70%) Arizona House of Representatives Speaker: James P. Weiers (R) D ber House of Representatives. All 90 legislators have two-year terms and are elected concurrently in November of even-numbered years. Term limits restrict legislators to four consecutive terms in the same office. (It is not uncommon for legislators to switch to the other chamber when they reach their eight-year maximum.) Legislators are elected from 30 districts, with voters in each district selecting one senator and two representatives. The districts are now redrawn by a citizen commission every decade after the federal census. Gerrymandering—the drawing of district boundaries to give an advantage to a party or group—has plagued Arizona since statehood. Following the 2000 census, only four of the 30 districts were competitive; the remaining districts all contained an overwhelming number of persons of the same party. This district map allowed Republicans to gain more than their fair share of seats in the legislature, although from 1912 to 1966, the Democrats were the major beneficiaries of gerrymandering. Gerrymandering reduces political competition overall so that Arizona legislative candidates often run unopposed or face reduced or nominal opposition. Legislative sessions—The Arizona Legislature meets for only one regular session each R Republicans: 33 (55%) Democrats: 27 (45%) Standing committees: 18 Female legislators: 18 (30%) Incumbents: 42 (70%) LAST SESSION STATISTICS (47th, 2nd Regular 2006) Session length: 165 days Bills introduced: 1,453 Bills passed: 438 Bills vetoed: 43 Line item veto: 1 Vetoes overriden: 1 year, beginning in January and typically lasting roughly 100 days. (The 2006 session ran an unusual 165 days.) An unlimited number of special sessions can be called by the governor or (more rarely) initiated by the legislature itself. If the session is called by the governor the legislature can only address the specific matters identified in the governor’s call. In recent years, the legislature has met for an average of three special sessions each year. Such sessions can last only a few hours or up to several months. It is customary for the governor to call a special session during a regular session when the state’s general appropriations bill is ready for consideration. This compels the legislature to drop all other business and focus exclusively on the budget. Even when the legislature is not in formal session, legislators often work on upcoming legislation, participate in meetings, and respond to constituent needs. A “citizen legislature”—The formal qualifications for serving in the legislature are fairly low: A legislator must only be at least 25 years old, an Arizona resident for three years, a county resident for one year, a registered voter, and English proficient. Because legislative service is only part-time and compensation is low (see below), most legislators have privatesector jobs on the side. This type of legislature is called a “citizen legislature” to distinguish it from legislatures like the U.S. Congress, which are made up of full-time, professional politicians. Citizen legislatures are fairly common on the state level. The typical Arizona legislator is a small business owner or employed in a business-related field such as real estate, insurance, or banking. That is, the citizen legislator needs to have an occupation with hours flexible enough to accommodate the demands of legislative service. Legislative compensation—Legislative pay in Arizona has always been low to preserve the citizen legislature concept. In the beginning, the state constitution capped the compensation at $420. Now, a citizen salary commission reviews salaries every two years and sends its recommendation to the voters as a ballot proposition. Since the system was instituted in 1972, the voters have rejected the Commission’s recommendation 16 out of 18 times. The Legislature currently receives an annual salary of $24,000 (approved in 1998). Frustrated with the low compensation, the Legislature has voted itself a controversial supplement in the form of a “per diem.” Legislators engaged in official business receive an extra $35 per day (Maricopa County legislators) or $60 per day (legislators outside of Maricopa County). Internal legislative organization—Leaders, parties, and standing committees play an important role in the day-to-day operation of the legislature. Each chamber chooses its leader by majority vote. (This is just a formality; in actual practice, the leaders are chosen by the majority party in a party caucus that precedes the opening session.) The Senate elects a President and the House elects a Speaker. The leaders preside over meetings of their respective chambers. They appoint other members to committees, choose the committees’ chairpersons, and remove members or chairs who are disloyal to the party’s agenda. The leaders also have significant powers over the passage of bills (discussed below) and they have various administrative powers (e.g., they hire staff, control the facilities, and approve per diem and other disbursements to members). Most legislative work is done in semi-permanent standing committees that are devoted to certain areas (e.g., education, health, transportation, appropriations). This allows legislators to develop expertise and handle legislative business more expeditiously. Members typically serve on two or more committees. Since the committees work on the principle of majority rule, the leaders carefully appoint members to committees to ensure that their party (i.e., the majority party) has a majority on every standing committee. This insures that the majority party can control all committee outcomes. How the lawmaking process works—Only a legislator can sponsor a bill although the impetus for most bills comes from other government officials, lobbyists for special interests, and citizens. The Legislature typically considers more than 1,000 bills during each regular session. Roughly two-thirds fail to make it through the process. Bills can begin in either chamber. The speaker/president assigns the bill to select standing committees in a process that can be manipulated to kill bills. The chair of the standing committee can also kill the bill by simply failing to schedule it for a public hearing. If a hearing occurs, committee members hear testimony on the bill and propose amendments. Only if a majority votes the bill out of committee does it proceed to its next committee for study. All bills ultimately go to the rules committee which determines whether the proposed law is in proper form and constitutional. Bills that successfully make it through the committee process (most don’t!) are debated in the Committee of the Whole (“COW”) where the bill’s language is finalized. If approved by COW the bill is scheduled for an official vote of the chamber (see sidebar for vote requirements). Bills that pass the first chamber go to the other for committee study in a similar but shortened process. Only if both houses pass the bill in identical form does it proceed to the governor. (If the second chamber passes the bill in a different form a conference committee, consisting of members of both chambers, may be created to craft a compromise. The compromise must be approved by each chamber before it can proceed to the governor.) If the governor vetoes the bill the Legislature can override the veto by a super majority (see sidebar) vote. Bills with emergency clauses, bills that appropriate money to keep government running, and new tax measures take effect immediately. All others sit for 90 days after the session ends to allow citizens to block the measure through the referendum process. If no referendum is perfected, the bills take effect. Prepared by Toni McClory toni.mcclory@gcmail.maricopa.edu Last updated: 12-10-06 IMPEACHMENT PRIMER Who can be impeached: Any state official other than a legislator. (Legislators are subject to expulsion by a 2/3 vote of their own chamber.) Grounds for impeachment: High crimes, misdemeanors, and malfeasance in office. Procedure: 1. House votes to impeach (simple majority vote). 2. Senate conducts trial and votes to convict (2/3 vote). Penalty: Removal from office. Under the Constitution’s “Dracula Clause” an official can also be barred from holding a public office in the state again. Who inherits the office: The governor typically appoints a replacement. If the governor is being impeached, the qualified constitutional successor (usually the secretary of state) inherits the office. VOTES NEEDED TO PASS BILLS Ordinary bills simple majority Appropriation bills simple majority Tax bills 2/3 Emergency bills 2/3 Veto overrides 2/3 or 3/4 depending upon the initial vote required to pass Constitutional referenda simple majority Statutory referenda simple majority Changes to voter-approved measures 3/4 ARIZONA LEGISLATURE: www.azleg.state.az.us Arizona’s Executive Branch ARIZONA’S CURRENT EXECUTIVE BRANCH Governor: Janet Napolitano (D) Secretary of State: Jan Brewer (R) Attorney General: Terry Goddard (D) Treasurer: Dean Martin (R) Superintendent. of Public Instruction: Tom Horne (R) State Mine Inspector: Joe Hart (R) Corporation Commission: Gary Pierce (R) Kristin Mayes (R) Jeff Hatch-Miller (R)* William Mundell (R)* Mike Gleason (R)* * seat up for election in 2008 A plural executive branch—Like most state governments Arizona has a “plural” execu- tive branch. Arizona elects eleven executive branch officials and has dozens of state agencies headed by independent multi-member boards. Under this arrangement no single official is in charge. This contrasts with the national government which has a single elective head (the president) and appointed subordinates. The elected members of the Arizona executive branch (in succession order) are: the governor, secretary of state, attorney general, treasurer, and superintendent of public instruction. In addition to the “big five,” Arizona elects a state mine inspector and a five-person corporation commission. Notably, Arizona has no lieutenant governor. Except for the corporation commissioners (who have staggered terms), the remaining officials are elected to four-year terms in off-presidential even-numbered years (e.g., 2006, 2010, 2014). This means that Arizona’s top officials are typically elected in low turnout elections. In the 2002 election, for example, only 30% of the voting age population voted. Term limits now restrict executive branch officials (other than mine inspector) to two consecutive terms. . The pros and cons of a plural executive branch—The drafters of Ari-zona’s consti- tution believed that having multiple elected officials would reduce corruption. (Territorial officials had been notorious for abusing power.) With a plural executive branch no single person has all the power, and multiple elected officials serve as watchdogs over each other. In addition, the voters have control over who heads sensitive departments such as utility regulation, mine safety, and the management of schools. To some degree this plural design has worked. In the past twenty years Arizona has weathered two major gubernatorial crises. Governor Evan Mecham was removed through the impeachment process in 1988 and Governor Fife Symington resigned following a criminal conviction in 1997. Having an independently-elected attorney general benefited the state in both instances. However, critics argue that a plural executive deprives the state of strong leadership. Friction and conflict can result when voters elect officials from different parties. Even officials from the same party do not always work well together—they may be political rivals or simply have different views. A plural branch also tends to reduce accountability because officials can blame each other for inaction or failures. Finally, the voters do not always elect officials with expertise (e.g., treasurers with financial backgrounds; school chiefs with educational experience.) The governor: first among equals—Arizonans expect their governor to be a forceful George W. P. Hunt was Arizona’s first governor. He was re-elected to office a record seven times. leader who can take charge of the bureaucracy and effectively manage the state’s needs. Although the state constitution gives the governor varied powers, nearly all are limited in significant ways. For example, the ability to hire and remove department heads is one way that chief executives control the bureaucracy. However, in Arizona some major departments are off limits because they are controlled by other elected officials (e.g., the department of education). And the governor cannot fire board members who head many important state agencies (e.g., the parole board and most occupational regulatory agencies). Similarly, the governor lacks the power to hire or fire most of the state’s workers who are civil servants. The governor plays a major role in the state’s budget process, but the legislature has the final say. The governor is the commander-in-chief of the state’s militia (National Guard), but the president can nationalize the Guard at any time. The governor can dictate the legislature’s agenda by calling it into a special session, but the legislature is not obligated to enact the legislation sought by the governor and can immediately adjourn. The governor has a veto power over legislation, including the more powerful line-item veto with respect to appropriation bills. However, the legislature can override the governor’s veto with a supermajority vote (although this is rarely done). The legislature can also bypass an anticipated veto by sending the measure to the people through the referendum process. (The governor has no veto over any citizen-initiated measures.) The governor has the power to appoint all appellate judges and most superior court judges. However, this is not comparable to the president’s power to appoint federal judges: Arizona’s governor is forced to appoint from a short list of candidates, state court judges do not serve for life, and state court judges must win periodic retention elections to remain in office. Finally, the governor’s clemency powers are also limited. Although the governor can grant reprieves (postponements in the carrying out of criminal sentences), commutations (reductions in sentences) and pardons (full forgiveness) the governor cannot act unless a state board approves clemency first. Additionally, the governor has no power over paroles (early release from prison) which are exclusively controlled by a state board. Historically, many Arizona governors have been overshadowed by powerful legislative leaders or attorney generals. However, Governor Bruce Babbitt (1978–86) demonstrated that strong political skills, an aggressive use of the veto power, and some luck, can make the governor the dominant person in state government even when the legislature is controlled by the opposing party. The advent of legislative term limits has also helped shift the balance of power from the legislature to the governor. Finally, governors can draw upon various informal powers. For example, the governor is the ceremonial “head of state” and usually attracts the most media coverage. The governor is usually the leader of his/her party. These informal powers can be used to build political support for the governor’s agenda. Other executive branch officials—The secretary of state is the chief elections official and maintains the state’s records and laws. This official is next-in-line of succession if something happens to the governor. (Since 1977, three secretary of states have inherited the top office through this means.) Wielding more real power is the attorney general, who serves as the state’s top legal advisor. Because the line between legal and policy advice is not clearcut, attorney generals can significantly influence the operation of state government. The attorney general represents the state in most non-criminal litigation and plays an important, but not exclusive, role in criminal law enforcement. (In Arizona most crimes are initially prosecuted by county attorneys, but the attorney general has supervisory powers and handles criminal appeals.) The treasurer is the top financial officer and collects, safeguards, and invests, and invests the state’s funds. The superintendent of public instruction manages the department of education which oversees the state’s K–12 schools and certifies its teachers. However, the superintendent’s authority is undercut by other officials and bodies that participate in school governance (e.g., the state board of education, locally elected school boards, school superintendents, and county superintendents). Arizona elects a state mine inspector because the constitution’s drafters feared that governors would appoint industryfriendly officials. The same rationale—mistrust of corporate influence—caused the framers to create an elected Corporation Commission. This body, (which recently expanded from three members to five), regulates public service corporations—the utility companies that provide gas, electricity, water, telephone and similar services. Because most of these businesses are monopolies, the commission determines the maximum rates they can charge and monitors the service that they provide. The corporation commission also licenses private corporations and securities issued in Arizona. Governor Janet Napolitano (D) 2003-present Largest State Agencies: Corrections (DOC) Economic Security (DES) Transportation (DOT) Health Services (DHS) AHCCCS Juvenile Corrections Revenue Administration (DOA) Attorney General Environmental Quality (DEQ) Major State Boards and Commissions: Accountancy Barbers Chiropractic Examiners Cosmetology Dental Examiners Education Executive Clemency Funeral Directors and Embalmers Industrial Commission Medical Examiners Nursing Opticians Parks Pharmacy School Facilities Regents (universities) Veterinary Medical Examiners Governor’s homepage: www.azgovernor.gov/ State of Arizona homepage: http://az.gov/webapp/portal/ Prepared by Toni McClory toni.mcclory@gcmail.maricopa.edu Last updated: 12-22-06 Arizona Judiciary ARIZONA’S APPELLATE COURTS Judicial Power: What Judges Do—The familiar role of judges as trial referees is only part of the story. Most people don’t realize that judges also make law and shape public policy. Appellate court judges do this when they interpret existing laws and constitutional provisions. Their interpretations become as binding as the original text. Arizona courts have shaped public policy in many important ways. In 1994 they declared the state’s method of funding public school improvements to be unconstitutional and ordered a more equitable system. In 1998 they struck down the citizen’s (first) Official English initiative, declaring that it violated free speech rights. When judges strike down laws on constitutional grounds they exercise a power known as judicial review. The Arizona Court System: an overview—Arizona’s state courts fall into two main Arizona Supreme Court 5 justices, 6-yr. terms Handles appeals from lower courts; special actions against state officials; suits between counties. Arizona Court of Appeals 22 judges, 6-yr. terms [Div.1 (Phx) = 16 judges; Div. 2 (Tuc) = 6 judges] Handles appeals from superior courts, the tax court, the Industrial Commission, and unemployment compensation cases. MAJOR TRIAL COURTS Superior Court 168 judges, 4-yr. terms [Maricopa= 93 judges] Handles serious criminal and civil cases (e.g., all felonies, private claims over $5,000, divorces, probate) and appeals from JP and municipal courts. LIMITED JURISDICTION COURTS Justice courts (JP) 85 judges, 4-yr. terms [Maricopa=23 precincts.] Mostly handles traffic cases, minor criminal cases (misdemeanors and petty offenses), private claims under $10,000; small claims division (cases under $2500); and conducts preliminary hearings in felony cases. Municipal (city) courts 129 judges, 4-yr. terms Mostly handles traffic cases, minor criminal cases (misdemeanors and petty offenses occurring within city limits) and violations of city ordinances. categories: general jurisdiction and limited jurisdiction courts. The former handle more serious cases covering a wider range. Limited jurisdiction courts mostly deal with traffic cases. Another way to classify courts is to distinguish between trial and appellate courts. Cases start out in trial courts. Typically, a single judge presides, witnesses give testimony, and physical evidence is presented. Either a jury or the judge decides the outcome. Appellate courts receive the case after trial is over. Their job is to determine whether the lower court proceedings were fair and proper. They do not hold trials or consider new evidence. Instead, a panel of judges listens to short arguments presented by the lawyers for each side. The court also reviews written briefs filed by the parties. After privately conferring, the appellate judges vote, with majority rule determining the outcome. The appellate court issues a formal written opinion setting forth the judges’ reasoning. These opinions are published and become part of the common law (judge-made law) of the state. Arizona’s Appellate Courts—Arizona has two appellate courts: the Arizona Supreme Court and the Arizona Court of Appeals. Most litigants have an automatic right to an appeal in the Court of Appeals. (When a criminal defendant is acquitted double jeopardy bars an appeal by the government.) Only death penalty cases have an automatic right to an appeal before the Supreme Court. The state’s highest court has discretionary jurisdiction and accepts only a small number of appeals each year. Appellate court justices serve for six-year terms and are chosen and retained by Merit Selection (see below). Superior Court—The superior court is the state’s major trial court. Each county has a su- perior court with multiple judges assigned to it. This court handles the most serious criminal and civil cases. All felonies are tried in superior court along with civil cases where more than $5,000 is at stake. Superior court also handles important family cases like dissolution of marriage and adoption, as well as probate (wills), and disputes over real property. Superior Court judges have four-year terms. Those in Pima and Maricopa County are chosen through Merit Selection. Superior Court judges in other counties are elected in non-partisan, contested elections. Limited Jurisdiction Courts—There a two limited jurisdiction courts: Justice (or “JP”) courts and municipal (city) courts. Together they handle the greatest volume of cases. City courts mostly deal with traffic cases, misdemeanors, and violations of city ordinances and codes. Most judges in these courts are appointed by city governments. Justice courts are organized by precincts within counties. Justice courts have similar criminal jurisdiction as city courts, but also handle private lawsuits where the amount in controversy is under $10,000. If less than $2500 is at stake the case can go to the small claims division of Justice court, where no lawyers are allowed. Litigating in small claims division is speedier and less costly. Justice courts also handle the preliminary hearings that proceed felony trials in superior court. Justices of the Peace are elected in contested elections and serve four-year terms. A persistent controversy surrounds the qualifications for JPs: Unlike like other courts, the judges do not have to be lawyers. Essentially, they need only be registered voters over the age of eighteen. Merit Selection—All Arizona general jurisdiction judges were originally elected in con- tested elections. In 1974 the system was revamped as a result of mounting criticism of judicial elections. Some reformers believed that ordinary citizens were not competent to choose the most qualified judges. Others were disturbed by the mounting costs of judicial campaigns. This meant that judges either had to be wealthy or successful fundraisers. Fundraising raised additional concerns because major contributors were typically big businesses and other special interests frequently involved in litigation. This put judicial integrity in issue, along with mudslinging campaigns that reduced respect for the entire judiciary. Accordingly, Arizona adopted Merit Selection (which in other parts of the country is known as the “Missouri Plan”). Merit Selection works as follows: Whenever there is judicial vacancy candidates apply to a judicial appointments commission. The commission screens applicants and sends at least three names to the governor. The state constitution prohibits all nominees from being from the same party and requires the commission to consider diversity as well as merit. The governor then appoints the judge from this short list. If the judge wants to remain on the bench, he/she must survive a retention election at the end of every term. In a retention election the judge’s name appears on the ballot and the voters are simply asked to vote “yes” or “no” as to whether the judge should be retained. If a majority vote no, a vacancy is created and the process begins anew with another appointment by the governor. Supporters of merit selection contend that it has increased the overall quality of judges, allowed younger, less affluent persons to serve, and has promoted judicial independence. Critics contend that Merit Selection has simply transferred the open politics of the electoral process to the manipulations of a narrower, less visible group of insiders who lobby the appointments commission. Retention elections—which require voters in Maricopa County to be knowledgeable about the performance of more than forty judges—are also problematic. Merit Selection currently applies to all appellate judges and to superior court judges in Maricopa and Pima counties. Jury Power in Arizona—The drafters of Arizona’s constitution did not trust government officials, including judges. Accordingly, they put several provisions in the constitution to ensure that jurors would always have the final say in tort cases (private injury lawsuits). For example, the Constitution prohibits the Legislature from passing any law that limits the amount of money that can be recovered in injury cases. It also recites that the jurors must decide whether defenses such as assumption of risk or contributory negligence should bar a person from recovering money. (In other states they are grounds for dismissal of the case.) These provisions have become controversial in modern times as some have argued for tort reform and restrictions on high jury verdicts. The voters have been asked to repeal these provisions on multiple occasions. To date, they have refused, reposing their trust in the common sense of the jury. COURT FILINGS BY COURT (2005) AZ Supreme Court 1,164 AZ Court of Appeals 3,871 Tax Court 1,019 Superior Court 205,516 JP Courts 856,153 Municipal courts 1,469,243 TOTAL 2,536,966 JURY TRIALS IN ARIZONA The Arizona Constitution gurantees the right to trial by jury, but the number of jurors required and the degree of agreement needed to reach a verdict varies: # Agreement needed Superior Court (felonies punishable by death or 30+ yrs) 12 unanimous Superior Court (other felonies) 8 unanimous Superior Court (civil cases) 8 6 JP & municipal courts (criminal) 6 unanimous JP (civil) 6 5 Prepared by Toni McClory toni.mcclory@gcmail.maricopa.edu Last updated: 12-22-06