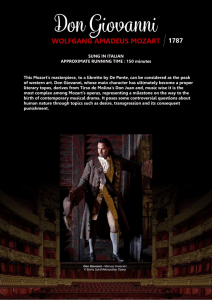

Don Giovanni Blocking

advertisement