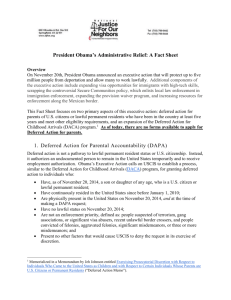

The Constitutionality of DAPA Part II: Faithfully Executing the Law

advertisement