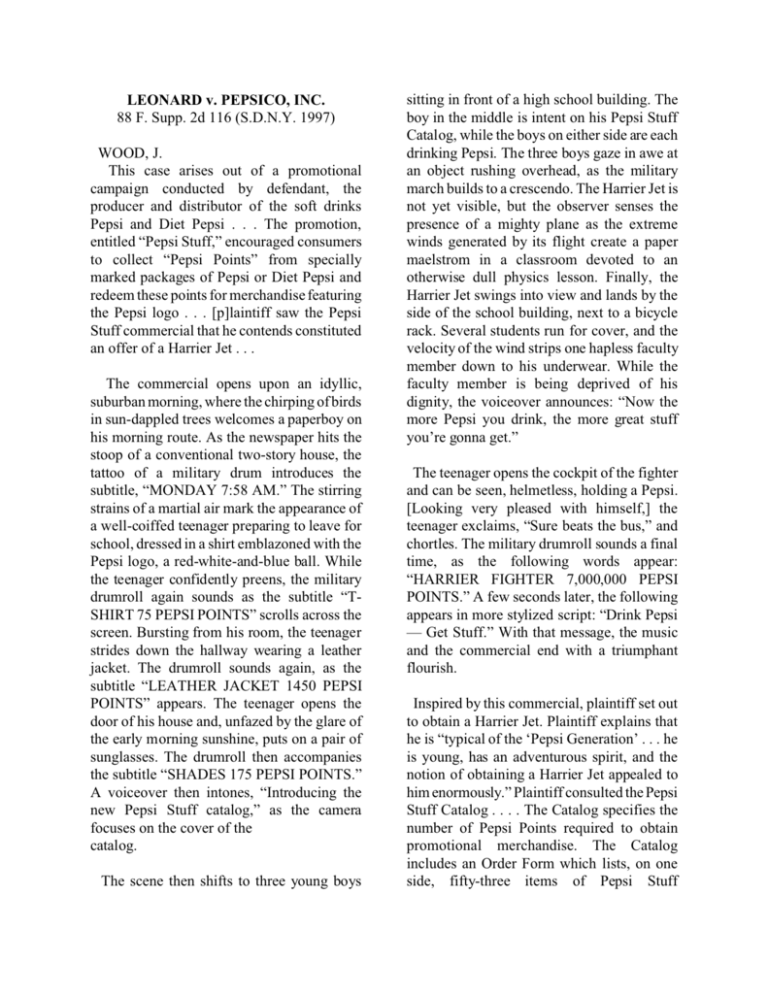

LEONARD v. PEPSICO, INC. 88 F. Supp. 2d 116 (S.D.N.Y. 1997

advertisement