Just Do It: How Nike Turned Disclosure into an Opportunity

advertisement

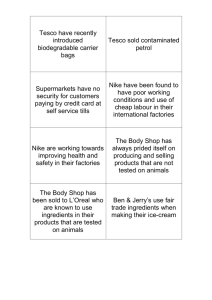

research insights Just Do It: How Nike Turned Disclosure into an Opportunity In April 2005, Nike surprised the business community by suddenly releasing its global database of nearly 750 factories worldwide. No laws presently require companies to transparently disclose the identity of its factories or suppliers within global supply chains. Yet, between the early 1990s and 2005, Nike had dramatically transformed. It went from denying responsibility for inhumane conditions in its factories to leading other companies in full disclosure — a strategic shift that illustrates how a firm can leverage increased transparency to mitigate risk and add value to the business. David Doorey (York University) conducted an indepth case study of this transformation, drawing on interviews with company executives, industry professionals experienced in managing supply chain labor practices, and representatives of unions and NGOs who were involved in the push for factory disclosure. In the early 1990s Nike executives began to see persistent reports of abusive labour conditions in their supplier factories as a risk to their brand image. Nike’s traditional line denying responsibility for conditions in these factories no longer satisfied a growing number of customers. On top of that, media images of children sewing Nike soccer balls and running shoes sent social activists, academics and journalists into a costly anti-Nike campaign. Nike leaders realized they needed a new strategy to deflect the growing criticism and improve their suppliers’ performance. Starting with the creation of a new labour practices department responsible for implementing and monitoring its code of conduct, Nike introduced a series of organizational changes designed to enable better monitoring of sources of risk associated with suppliers’ labour practices. These changes included: • Conduct a basic audit: Nike introduced the SHAPE internal monitoring system intended to provide it with an initial assessment of whether a proposed new factory was at least in the ballpark in terms of satisfying the code of conduct. Factories flagged as high risk would also undergo a more comprehensive “M-audit.” • Create a corporate responsibility and compliance division: Senior management created a new division that housed several departments to facilitate the integration of corporate responsibility issues throughout the business. This brought together sustainability and compliance employees working across product groups. • Assign field managers: Nike assigned field managers to the various regions. They were responsible for monitoring day-to-day compliance with labour laws and the Nike code. • • Establish a global database: Head office developed a comprehensive database to help track the global supply chain and access audits conducted in the field. Initiate external expert review: In 2004, Nike invited a panel of external experts to review a draft of its 2004 corporate responsibility report. The committee concluded that Nike would not receive the credit it craved from the NGO community unless it released the names and addresses of its entire factory database. “Companies should replace defensiveness with a proactive strategy that uses code monitoring and enforcement — and eventually full disclosure — to their advantage” These monitoring and enforcement systems created confidence internally, which was necessary before releasing the list externally in 2005. Nike turned this unprecedented move into a lucrative marketing opportunity that outweighed competitive risks associated with factory disclosure. It advertised its new transparency as evidence of its new commitment to labour practices. In fact, the company turned its full disclosure into a badge of honour among the apparel industry. Seeing the success that Nike enjoyed from this move, many of Nikes competitors disclosed their factory lists, including Levis, Timberland, Puma, Adidas and Reebok. What can you learn from Nike’s experience? 1. A systematic supply chain monitoring mechanism can help address the worst practices. Moreover, this mechanism is foundational prior to adopting greater transparency. If you don’t know about it, you can’t fix it. 2. A defensive strategy is not a realistic long-term approach. Companies have difficulty hiding from the media and should replace defensiveness with a proactive strategy that uses code monitoring and enforcement — and eventually full disclosure — to their advantage. Source: Doorey, David J. (2011) The Transparent Supply Chain: from Resistance to Implementation at Nike and Levi-Strauss. Journal of Business Ethics, 103, 587-603. Summary by: Bushra Tobah and the NBS team February 2012