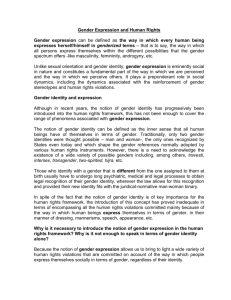

Gender Stereotypes: Masculinity and Femininity

advertisement