Penn's Self-Study - Office of the Provost

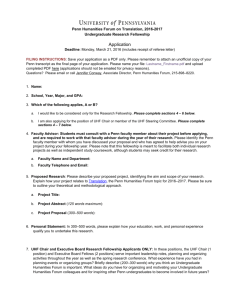

advertisement