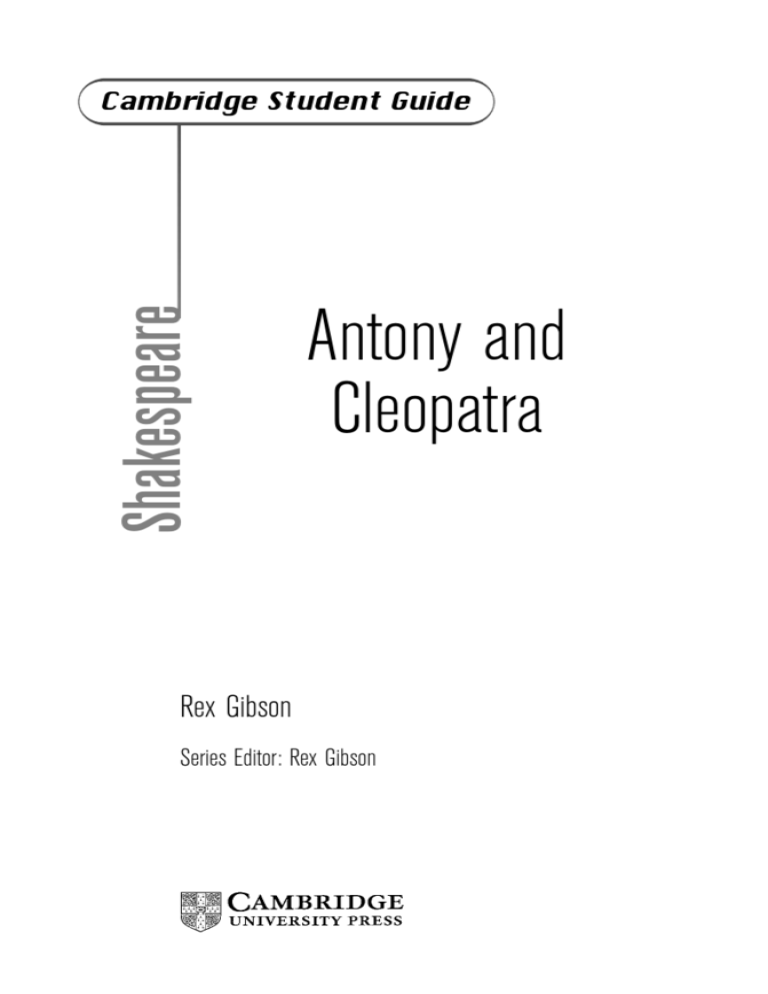

Antony and Cleopatra - Cambridge University Press

advertisement

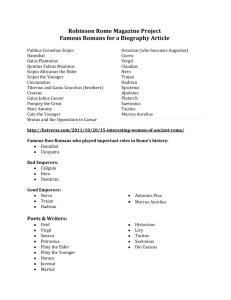

Shakespeare Cambridge Student Guide Antony and Cleopatra Rex Gibson Series Editor: Rex Gibson PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011–4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcón 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org © Cambridge University Press 2004 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2004 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface 9.5/12pt Scala System QuarkXPress® A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0 521 53858 0 paperback Cover image: © Getty Images/PhotoDisc Contents Introduction Before the play begins Commentary Contexts What did Shakespeare write? What did Shakespeare read? What was Shakespeare’s England like? Queen Elizabeth I King James I King Christian IV Rome and Egypt Changing ideas of honour Shakespeare’s own life Language Imagery Antithesis Repetition Lists Verse and prose Critical approaches Traditional criticism Modern criticism Political criticism Feminist criticism Performance criticism Psychoanalytic criticism Postmodern criticism Organising your responses Writing about an extract Writing an essay Writing about character A note on examiners Resources Books Films and audio books Antony and Cleopatra on the Web 4 5 6 70 70 71 74 75 76 78 79 80 81 82 82 87 88 90 91 92 92 96 98 100 103 106 107 108 109 117 122 124 125 125 128 128 Contents 3 Commentary Act 1 Scene 1 Nay, but this dotage of our general’s O’erflows the measure. (lines 1–2) The scene is set in Cleopatra’s palace in Alexandria, and Philo’s first words condemn Antony’s infatuation with Cleopatra. Philo protests that Antony, once the model for all noble warriors, has lost all military qualities and has become merely ‘the bellows and the fan / To cool a gipsy’s lust’. It is significant that here Shakespeare provides a stage direction which is the visual equivalent of Philo’s words, having Cleopatra enter ‘with eunuchs fanning her’. And the word ‘gipsy’ contemptuously reveals Rome’s attitude to Egypt and her queen. Shakespeare uses the Roman Philo to open and close Scene 1 as a choric commentator. He exposes the vast gap in values and behaviour between Egypt and Rome. Philo invites Demetrius – and the audience – to witness Antony’s degeneration from a triumvir (one of the three political masters of the world) into the plaything of a whore: Look where they come. Take but good note, and you shall see in him The triple pillar of the world transformed Into a strumpet’s fool. Behold and see. (lines 10–13) Every director considers carefully how to stage the audience’s first sight of Antony and Cleopatra. Traditional productions often staged a ceremonial entrance of much grandeur and dignity, but most modern productions present the lovers playfully engaged with each other, locked in embrace or tugging at each other’s clothing. In the 2002 Royal Shakespeare Company production, the lovers were already on stage, with Cleopatra sensuously rubbing oil into Antony’s back. The dramatic intention was to give a context to their first exchange in which Cleopatra demands to know how much Antony loves her. Antony dismisses as worthless the value of love that can be calculated, and when Cleopatra claims she will set a limit (‘bourn’) on his love, he 6 Commentary responds in a style that will characterise the whole play, hyperbole (obviously exaggerated language): Then must thou needs find out new heaven, new earth. (line 17) The lovers’ playful talk is interrupted by a messenger from Rome. Antony, irritated, demands to hear the news in brief, but Cleopatra mocks him, saying it is perhaps about his wife Fulvia’s anger, or a peremptory command from young Caesar to conquer or liberate another kingdom. She continues to taunt him, claiming he blushes at the thought of being vassal (‘homager’) to Caesar or scolded by Fulvia. Cleopatra’s teasing prompts Antony to another hyperbolic outburst: Let Rome in Tiber melt and the wide arch Of the ranged empire fall! (lines 35–6) In the same extravagant style, Antony declares he cares only to be with Cleopatra, embracing or kissing her as he claims, ‘The nobleness of life / Is to do thus’. As if issuing a public proclamation, he calls on the world to recognise (‘weet’) that he and Cleopatra have no equals in love: ‘We stand up peerless’. But Cleopatra continues to tease, accusing him of outrageous lying, ‘Excellent falsehood!’, and reminding him she is no fool like him. Antony protests he is ‘stirred’ (sexually excited) only by her, and proposes pleasure rather than ‘conference harsh’. Looking forward to ‘sport’, he refuses to hear any message from Rome, praises Cleopatra, and declares that tonight they will wander the streets, observing the people of Alexandria. Shakespeare is using here a quotation from Plutarch (see page 71) which claimed that Antony and Cleopatra would sometimes disguise themselves as slaves to visit the city and watch and quarrel with its citizens. Antony dismisses the messenger and the stage empties, leaving only Philo and Demetrius to comment with dismay on what they have seen and heard. Both note how slightly Antony values Caesar and that he no longer displays the greatness he once possessed. It confirms what malicious gossips have been saying in Rome. Demetrius’ expression ‘approves the common liar’ (confirms what liars say is true) expresses another characteristic which will recur throughout the Act 1 Scene 1 7 play: paradox. Neither Philo nor Demetrius will appear in the play again, but they have served their dramatic function to draw attention to: ● the vast difference between Egypt and Rome; ● Antony’s change from noble soldier to infatuated lover; ● potential antagonism between Antony and Caesar. Act 1 Scene 2 The first 70 lines of Scene 2 reveal the frivolous, pleasure-seeking, sexually obsessed nature of Cleopatra’s court. Charmian and Iras, ladies-in-waiting to the queen, joke together as their fortunes are told by the Soothsayer. His formally spoken prophecies contain ominous meanings, but the two women refuse to see any menace in his words. Both women’s chatter is full of sexual innuendo: ‘figs’ were thought to look like vaginas; ‘an oily palm’ was believed to signify sensuality; Iras’ claim that she would prefer an inch ‘Not in my husband’s nose’ is obviously a phallic joke; and both women tease Alexas unmercifully about his future as a cuckold (deceived husband). Their banter is interrupted by Cleopatra, who is evidently concerned about a change in Antony: He was disposed to mirth, but on the sudden A Roman thought hath struck him. (lines 77–8) Antony is seen approaching, but Cleopatra determines not to speak with him, and the entire court exits with her, leaving only Antony and the messenger on stage. It is an abrupt mood change, as the relaxed atmosphere of Egypt gives way to Antony’s ‘Roman thought’: reminders of duty, discipline and military affairs. The world of politics is forcing itself into the scene, opposing the preoccupation with love and idle pleasure the play has so far presented. Antony hears the news that the armies of his wife and brother have fought against each other, but then united to fight Octavius Caesar, who has defeated them and driven them out of Italy. The messenger has even worse news, but is afraid to tell it because it might cause him to be punished. Antony’s order that he should report it reveals the stoical and fearless nature of his character (and is in marked contrast with how Cleopatra will treat a messenger who brings bad news in Act 2 Scene 5): 8 Commentary Things that are past are done, with me. ’Tis thus: Who tells me true, though in his tale lie death, I hear him as he flattered. (lines 93–5) The messenger reports that the victorious Parthians have occupied Roman provinces from Syria to the shores of Asia (modern Turkey). Antony knows that what the messenger is still afraid to report is that such Roman defeats are due to his (Antony’s) neglect of his military obligations. He also knows that everyone in Rome is blaming his infatuation with Cleopatra for his dereliction of duty, and he demands that the messenger scold him just as Fulvia would. But he dismisses the messenger and, as he waits for further news, determines to abandon his life of lust and ease with Cleopatra and return to his political and military responsibilities as a Roman: These strong Egyptian fetters I must break, Or lose myself in dotage. (lines 112–13) As he makes his resolve, yet another messenger brings news of Fulvia’s death. Antony is moved to regret. Although he had often wished his wife dead, he now wishes her alive again. The thought prompts him again to reflect on his own state, and he feels the ‘present pleasure’ of Egypt losing its attraction. He resolves again to leave Cleopatra, ‘I must from this enchanting queen break off’, and tells Enobarbus his decision. Enobarbus makes a joke of it, saying Cleopatra will react passionately to his departure. He puns on ‘dies’ and ‘dying’, which Shakespeare’s audiences knew could mean ‘reach sexual orgasm’. Antony, seemingly preoccupied, merely responds, ‘She is cunning past man’s thought.’ His words prompt Enobarbus to describe Cleopatra in what will be seen to be his typically sardonic style, as he ridicules Cleopatra’s extreme feelings: Alack, sir, no, her passions are made of nothing but the finest part of pure love. We cannot call her winds and waters sighs and tears; they are greater storms and tempests than almanacs can report. (lines 142–5) Enobarbus similarly mocks Antony’s fervent wish, ‘Would I had never seen her!’ On hearing of Fulvia’s death, Enobarbus offers consolation Act 1 Scene 2 9