The Elasticity of Taxable Income: Estimates and

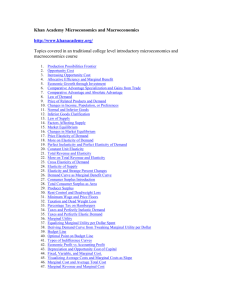

advertisement