Notes on Excess Burden (EB) Our goal is to calculate the excess

advertisement

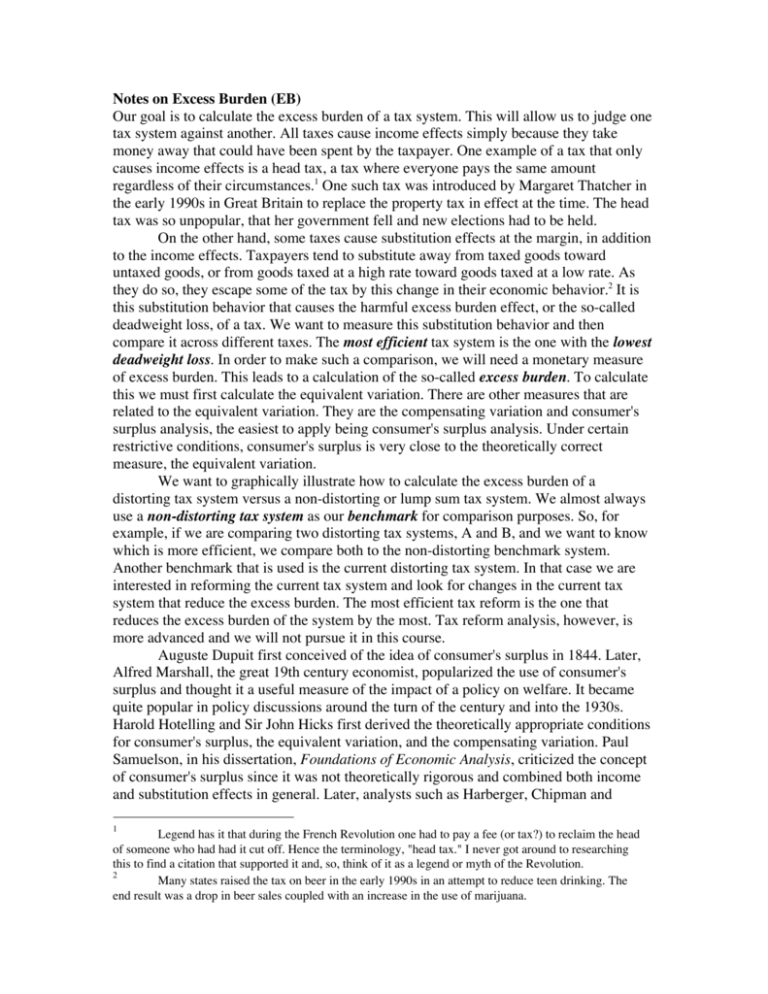

Notes on Excess Burden (EB) Our goal is to calculate the excess burden of a tax system. This will allow us to judge one tax system against another. All taxes cause income effects simply because they take money away that could have been spent by the taxpayer. One example of a tax that only causes income effects is a head tax, a tax where everyone pays the same amount regardless of their circumstances.1 One such tax was introduced by Margaret Thatcher in the early 1990s in Great Britain to replace the property tax in effect at the time. The head tax was so unpopular, that her government fell and new elections had to be held. On the other hand, some taxes cause substitution effects at the margin, in addition to the income effects. Taxpayers tend to substitute away from taxed goods toward untaxed goods, or from goods taxed at a high rate toward goods taxed at a low rate. As they do so, they escape some of the tax by this change in their economic behavior.2 It is this substitution behavior that causes the harmful excess burden effect, or the so-called deadweight loss, of a tax. We want to measure this substitution behavior and then compare it across different taxes. The most efficient tax system is the one with the lowest deadweight loss. In order to make such a comparison, we will need a monetary measure of excess burden. This leads to a calculation of the so-called excess burden. To calculate this we must first calculate the equivalent variation. There are other measures that are related to the equivalent variation. They are the compensating variation and consumer's surplus analysis, the easiest to apply being consumer's surplus analysis. Under certain restrictive conditions, consumer's surplus is very close to the theoretically correct measure, the equivalent variation. We want to graphically illustrate how to calculate the excess burden of a distorting tax system versus a non-distorting or lump sum tax system. We almost always use a non-distorting tax system as our benchmark for comparison purposes. So, for example, if we are comparing two distorting tax systems, A and B, and we want to know which is more efficient, we compare both to the non-distorting benchmark system. Another benchmark that is used is the current distorting tax system. In that case we are interested in reforming the current tax system and look for changes in the current tax system that reduce the excess burden. The most efficient tax reform is the one that reduces the excess burden of the system by the most. Tax reform analysis, however, is more advanced and we will not pursue it in this course. Auguste Dupuit first conceived of the idea of consumer's surplus in 1844. Later, Alfred Marshall, the great 19th century economist, popularized the use of consumer's surplus and thought it a useful measure of the impact of a policy on welfare. It became quite popular in policy discussions around the turn of the century and into the 1930s. Harold Hotelling and Sir John Hicks first derived the theoretically appropriate conditions for consumer's surplus, the equivalent variation, and the compensating variation. Paul Samuelson, in his dissertation, Foundations of Economic Analysis, criticized the concept of consumer's surplus since it was not theoretically rigorous and combined both income and substitution effects in general. Later, analysts such as Harberger, Chipman and 1 Legend has it that during the French Revolution one had to pay a fee (or tax?) to reclaim the head of someone who had had it cut off. Hence the terminology, "head tax." I never got around to researching this to find a citation that supported it and, so, think of it as a legend or myth of the Revolution. 2 Many states raised the tax on beer in the early 1990s in an attempt to reduce teen drinking. The end result was a drop in beer sales coupled with an increase in the use of marijuana. Moore, Diamond and Mcfadden, Diewert, Hausman, and Kay put the various concepts on a theoretically rigorous basis using advanced tools of microeconomics. We will present a simple graphical analysis in what follows. There are several steps in calculating the EB for an individual taxpayer. Suppose there are two goods, movies and everything else, and we impose a tax on movies. A tax on movies raises the consumer price of a movie and will cause the budget line to swivel in from A' to B', as depicted below because relative prices change when the tax is imposed. First step: everything else (E) A=B b 0 a U B' b A' movies (M) To see this note that the budget constraint before the tax is w = pM + qE, where w is labor income, p is the price per movie, M is the quantity of movies, q is the price of everything else, and E is a "good" called everything else. The two intercepts for this equation are the ordered pairs (w/p, 0) and (0, w/q). (When E = 0, we have w = pM, or M = w/p as the horizontal intercept, and similarly for the other intercept.) The budget constraint after the tax is w = (p + t)M + qE, where t is the tax rate on movies. The two intercepts are (w/(p+t), 0) and (0, w/q). Only the horizontal intercept is affected by the tax. So the budget line swivels in from A' to B'. Intuitively, the tax reduces income and causes the budget "triangle" given by A0A' to shrink to B0B'. For simplicity, assume q = 1. The consumer will move from point a to point b in the diagram as the tax on movies is imposed. Since she is still consuming some movies every month, the government will collect tax revenue from her in the amount tM, where M is the tax base. What are we to compare the distorting tax on movies to? Every tax causes an income effect since the taxpayer has less income after paying the tax. However, some taxes also cause a substitution effect and hence an excess burden. A non-distorting tax only causes an income effect. So if we compare the distorting tax to the non-distorting tax, we can isolate the substitution effect and measure the excess burden of the distorting tax on movies. A non-distorting tax does not alter relative prices but only causes an income effect. Therefore, it only causes the budget line to shift back in a parallel way. This is depicted as the shift from AA' to CC' below. If the non-distorting tax had been imposed the consumer would have chosen point c. Second step: everything else (E) w=A=B w-T=C a c U c C' A' movies (M) In the following diagram we have combined the previous two for comparison purposes. Since both budget lines BB' and CC' go through the same point, point b, they raise the same revenue at that point. Third step: everything else (E) w=A=B T w-T=C b a c c U b U B' D' C' A' movies (M) To prove this, note that the consumption bundle (M, E) is the same at point b for the two budget lines and hence the two taxes. Given this, consider the following. The taxpayer's budget under the distorting tax is w = (p +t) M + qE. The budget under the lump sum tax is w - T = pM + qE, where T is the lump sum tax. Subtract the second equation from the first, w - (w - T ) = (p + t) M + qE - (pM + qE), at point b, or, T = t . M. So the two tax systems raise the same tax revenue at point b. Point c is also on the non-distorting tax budget line and so raises the same revenue as the distorting tax at point b. In fact, every point on the CC' budget line raises the same amount of revenue. Also notice that as we move down the BB' budget line M increases and so the amount of tax revenue raised under the tax on movies increases. Finally, the distance between points A and C is the amount of the tax revenue collected. However, there is one difference. Notice that point c, where the individual pays the lump sum tax, is on a higher indifference curve than point b, where the individual pays the distorting tax, even though both taxes raise the same amount of tax revenue. The difference in utility, Uc - Ub, is the loss in welfare due to the distortion caused by the tax on movies, relative to the non-distorting tax. We want to calculate a monetary measure of the difference in utility, Uc - Ub. First, we must calculate the equivalent variation. To calculate the equivalent variation we start at point a and ask how much income we must take away to achieve the same utility at point b but at the original prices. This gives us point d and budget line DD'. Thus, the budgets BB' and DD' are equivalent in that they achieve the same level of utility so Ud = Ub. The equivalent variation (EV) of the distorting tax system is the vertical distance between A and D. Fourth step: everything else (E) A=B EV D b a U d B' c Ud D' A' movies (M) Next, we must subtract off the tax revenue collected from the EV. This is because the tax revenue collected has a positive value to society. Recall that the lump sum tax system collects the same amount of revenue as the distorting tax system. This is given by point C on the vertical axis. Thus, the distance between A and C is the tax revenue collected. Finally, the excess burden is defined as EB = EV - T Therefore, the excess burden is the distance between points C and D on the vertical axis. It is a dollar measure of the difference in utility between the distorting and non-distorting tax systems. (Also not that b and d are on the same indifference curve so utility is the same, Ub = Ud.) Fifth Step: everything else (E) A=B EV T EB C D b a c U d B' c Ud D' C' A' movies (M) Next, consider the case where preferences are 'L-shaped' so that there are no substitution possibilities. The tax on movies moves the taxpayer to point b as before. However, the lump sum tax that raises the same amount of revenue also moves the taxpayer to point b, where b = c. Now points b and c from the other diagrams coincide. There is no excess burden in this case. Why? Because there is no way the consumer can everything else (E) A=B a C b c B' D' C' A' movies (M) substitute away from movies and escape part of the tax. Note that both taxes cause the same income effects. This is because they raise the same amount of revenue. This is suggestive that the excess burden of a tax depends on substitution possibilities at the margin. Without such possibilities, there is no deadweight loss. The most efficient tax system is the one with the smallest deadweight loss for a given amount of tax revenue, all other things constant. We can calculate the excess burden for every tax system and then choose the system for which it is the smallest, yet raises enough revenue to meet the government's need. This would be the most efficient tax system. The idea is to calculate the excess burden for each tax system for an individual taxpayer. This gives us a dollar amount that is equivalent to the loss in utility from the distortions of the tax system for the individual taxpayer. The one with the lowest excess burden is the most efficient system for that taxpayer. Adding up across all taxpayers and choosing the system with the lowest total excess burden would presumably give us the most efficient tax system. There are several problems with this analysis, however. First, we require micro data on each taxpayer. Unfortunately, we will probably not have this sort of data for everyone. We will probably only have market data that aggregates across all people buying the taxed goods. Implicitly, when such data is used, it is assumed that we can add up across different individuals to calculate the equivalent variation of a tax. Second, even if we had data on individuals, can we really add the excess burden for one taxpayer to that of another? Doing so involves a value judgment because it presumes the two individuals are ranked in the same way by society. However, this kind of ranking cannot be done objectively. To simply add the numbers together assumes that the people are to be treated in the same way. In fact, society might feel differently about the two people. For example, if one is rich and the other poor, many would suggest weighting the poor person's deadweight loss greater than the rich person's loss when adding them up. So equity will always be an issue. Indeed, many goods that have low excess burden are also necessities and thus have a very low-income elasticity. This means that poor people buy more of these goods than rich people as a part of their budget, e.g., hamburger. Efficiency would have us impose high taxes on such goods because the excess burden is low. However, imposing high taxes on the poor might be viewed as inequitable. This is known as the equity - efficiency tradeoff. Finally, we can relate the previous diagrams to the standard deadweight loss or excess burden triangle. The following demand diagram matches up with the fifth step. Essentially, the consumer price rises by the tax rate t. Dw is the normal observable demand curve that holds income w constant and allows the price to change. Notice that as price increases and we move up this demand curve, the consumer is worse off in the sense that they are moving to lower indifference curves. So utility is changing along the usual demand curve. As price rises, utility falls, and as price falls, utility increases. On the other hand, Du is the utility constant demand curve that holds the utility level constant instead. Recall from the fifth step that points b and d are on the same indifference curve. However, the slope is steeper for b than d, reflecting the higher price of m due to the tax. These points correspond to the points b and d in the diagram below. The starting point is point a again. At point a we impose the tax on movies and the budget line swivels in as depicted in the previous diagrams and the price rises in the demand diagram below. We then observe the consumer moving from point a to point b in all the diagrams. We wish to calculate the excess burden using the demand curve below. If we use the usual demand curve that holds income constant, we would estimate the excess burden of the tax as the triangle abe. However, this would not match up with step 5 and the EB calculated there, which is correct since it compares points b and d. Instead, we should use the utility constant demand curve that goes through points b and d. The correct calculation of the excess burden is triangle bed. The consumer's surplus overestimates the excess burden of the tax in this case. Triangle bed coincides with our previous calculation of the EV and EB in step 5, i.e., distance CD is a dollar measure of the EB of the distorting tax and this coincides with the triangle bed below. p b t Revenue EB e a d D Du w M Recall that the excess burden of a tax or subsidy is caused by artificially changing relative prices. Whenever there is a change in relative prices two effects are created, a substitution effect and an income effect. When a price rises, people naturally substitute away from the good toward other commodities as much as possible. This is where the distortion comes from. And, when a price rises, there is less real income for buying everything else and the consumer's utility falls. When the price of a movie p rises, m falls because of the substitution effect and m falls because of the income effect if m is a normal good. What if m is an inferior good? The substitution effect still works in the direction of reducing m. However, m increases because of the income effect! If this latter effect is larger in magnitude than the substitution effect, we would observe m increasing as its price increased and demand would appear to slope upward! This is directly applicable to the case of goods in inelastic demand. Consider the case of an inelastic demand curve, say movies. The price rises by the tax rate on movies and observed demand doesn't change at all making the observed demand curve perfectly inelastic. As the price rises, we move from a to b in the two diagrams below. Does this mean there is no excess burden? No. What it means is the substitution effect and the income effect are perfectly offsetting one another and the good is an inferior good. As price increases, consumers substitute away from the good and m falls. However, since it is an inferior good and real income has fallen, they buy more of it because of the income effect. The two effects cancel one another so observed demand does not respond. The true excess burden is the gap in the dashed lines on the left and this coincides with the triangle bad on the right. The correct way to calculate the excess burden of a tax is to calculate the triangle under the utility constant demand curve, not the observed demand curve. p E a b EB t Revenue b c d a D d M Du w M (To see that this is an inferior good, notice that if we were at d in the left diagram and gave the consumer more income she would move to c and then to point a as income continued to increase. As income increases, she is consuming less M and more E.) Several remarks are in order. If distorting taxes are imposed on other goods as well, we can add up the EB for each tax for the individual consumer to get a total excess burden for the entire tax system for the individual consumer. Why? Because they are all measured in dollars. Second, it is an open question as to whether we can compare the EB for one consumer with that of another. If all individuals were identical we could. In that case it makes sense to add up the EB across all taxpayers to get a total EB. If all individuals only differ in their income we still could add up across taxpayers under certain conditions having to do with solving the so-called aggregation problem. This is beyond the scope of this class, however. Finally, the interpretation of our dollar measure of the EB is the following. Compare two tax systems, one that distorts economic decision-making at the margin and one that does not. The EB is the amount of income we would have to give the consumer so she is as well off confronting the distorting tax system as she would be if she paid the non-distorting tax instead. To calculate this, compute the excess burden triangle under the utility constant demand curve. An important application of this is to labor supply. Observed labor supply functions tend to be very price inelastic. This is because of offsetting income and substitution effects. When the wage rises, there is substitution toward work and away from leisure and consumption. And real income rises when the wage increases. If leisure is a normal good, leisure will increase and work will fall. So the two effects work in o opposite directions on labor supply. Recall our model of labor supply. Utility depends on leisure and consumption, U(L, C) and the budget constraint is given by A + 24w = wL + C, where the price of consumption is equal to one, A is asset income, and essentially the wage w is the opportunity cost of leisure. The time constraint is 24 = H + L where H is hours worked. This information is graphed below. Note that the observed supply of labor curve that holds income constant SI is perfectly inelastic at point a. The demand for labor is assumed to be perfectly elastic at the going wage w. Hit the market with a tax and the wage falls to w - t. The budget line swivels down through point b but labor supply appears to be unaffected by the drop in the net wage. Con A + 24w EB d a c Uc b A Ub 24 H L A lump sum tax that generates the same amount of revenue is given by the dashed line through points b and c. The gap between Uc and Ub is a measure of the deadweight loss or excess burden of the distorting labor income tax relative to the non-distorting tax. A dollar measure of this is given by the distance between the two dashed parallel lines on the vertical axis on the left, denoted EB. Notice that leisure is a normal good. If we start at point d and give the consumer more income, she will move from d to c to a, and we would observe leisure increasing and labor supply falling. The following diagram matches up with the previous one. The starting point is point a. Impose the tax and demand shifts down but we do not observe the agent changing her labor supply. The excess burden of the labor income tax is given by the triangle abd. Notice that the utility constant supply curve is upward sloping. This reflects the substitution effect.