Cultural encounters: Western scholarship and Fang

statuary from Equatorial Africa

Wilfried van Damme

In this inaugural address, delivered on the acceptance of an extraordinary professorship at

Tilburg University, Netherlands, in 2011, Wilfried van Damme examines three approaches

that have been characteristically applied within the Western anthropology of art during the

last half century. Illustrating these approaches with reference to the study of Fang statuary

from equatorial Africa, he discusses a stylistic approach, focusing on anatomical details and

proportions of Fang anthropomorphic sculptures; a culturalist approach, highlighting the

local meaning and values these sculptures express; and a postcolonial approach, dealing

with the Western appropriation and commodification of Fang statues.

Wilfried van Damme is a lecturer in world art studies at Leiden University and an

extraordinary professor of the anthropology of art and aesthetics at Tilburg University,

Netherlands. He is the author of Beauty in Context: Towards an Anthropological Approach to

Aesthetics (Leiden, 1996). Together with Kitty Zijlmans, he edited the seminal volume World

Art Studies: Exploring Concepts and Approach (Amsterdam, 2008). His present scholarly

interests include the intellectual history of Western studies of art and aesthetics outside the

West.

Journal of Art Historiography Number 11 December 2014

Cultural Encounters:

Western Scholarship

and Fang Statuary from

Equatorial Africa

Lecture, delivered on the official acceptance of the office of Extraordinary

Professor of “Ethno-Aesthetics: Tropical Art in an Intercultural and Interdisciplinary

Perspective” at Tilburg University on 4 February 2011 by Wilfried van Damme.

The extraordinary chair “Ethno-Aesthetics: Tropical Art in an Intercultural and Interdisciplinary Perspective”

is endowed by the Treub Foundation for Scientific Research in the Tropics.

Western Scholarship and Fang Statuary from Equatorial Africa 1

© Tilburg University, The Netherlands, 2011

ISBN: 978-94-61670-13-7

All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission must be obtained from the

publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction, storage in a retrieval system, or transmission in any form or by

any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise.

www.tilburguniversity.edu

Mijnheer De Rector Magnificus,

Leden van het Bestuur van de Maatschappij voor Wetenschappelijk

Onderzoek in de Tropen (Treub Maatschappij),

Zeer gewaardeerde toehoorders

In his book Pathfinders: A Global History of Exploration, the world historian Felipe

Fernández-Armesto suggests dividing the history of humanity into two parts: divergence

and convergence. Divergence refers to the gradual drifting apart of human populations,

after our species, Homo sapiens, had arisen in Africa some 200,000 years ago. Human

dispersal became especially marked when, more than 100,000 years later, people left

the continent eventually to colonize the rest of the habitable world. The process of divergence takes up by far the largest part of human history. Convergence, as discussed by

Fernández-Armesto, is a much more recent phenomenon, and refers to the reconnecting

of human populations over ever larger distances. Initiating this coming together again

of groups of humans, it is stressed, are voyages of exploration, prompted by a spirit of

adventure and commerce.1

As befits a world historian, Fernández-Armesto considers the process of gradual convergence from a multifocal point of view, discussing the geographical explorations of,

say, Chinese, Europeans, and Meso-Americans alike. Convergence not only issues from

various places and dates in recent human history, but can be seen to operate on various

geographical scales. When it comes to convergence on a global scale, the beginnings

of this process are to be found in Europe around 1500. It is here and then that indigenous seafarers started not only to intensify contacts with Africa, India, and China, but to

connect the “Old World” with the Americas and later Australia and the island worlds of

the Pacific. Human populations that had diverged sometimes tens of millennia ago were

slowly beginning to be incorporated into global networks, albeit not always to their own

consent, eventually leading to the degree of interconnectedness that characterizes our

world today – again, not to everyone’s satisfaction.

The reconnaissance of ever larger parts of the globe, wherever it was instigated, led

to a substantial extension of geographical and maritime knowledge, as described by

Fernández-Armesto. However, extension of knowledge also occurred on other planes. The

increased spatial interconnections engendered by exploration led to a growing awareness

of the existence of other peoples and their cultural traditions. This in turn prompted the

slow accumulation of knowledge about these other human populations, their customs,

beliefs, and cultural products. This is a process that again occurred in various places

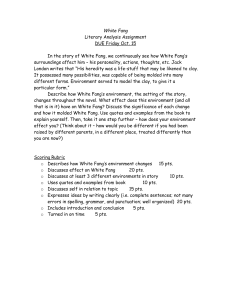

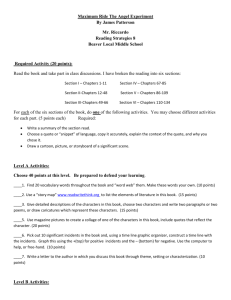

Western Scholarship and Fang Statuary from Equatorial Africa 3

around the globe, as attested, for example, in the Islamic world, Europe, China, and Japan

(Fig. 1). In some cases, the interest in other peoples and their cultures would eventually

lead to asking questions about the human condition more generally. This quest for what

it means to be human, which should arguably be at the forefront of the humanities today,

would also profit from taking into account current insights into humans’ shared bioevolutionary history. Indeed, no “understanding society,” Tilburg University’s motto, without

understanding the human animals that make it up.

Fig. 1 Dutch woman and man ( from: Nishikawa Joken, Zoho Kaitsu Shoko. Kyoto: Kakuyo Shorin, 1708;

photograph: World Imaging, Wikimedia Commons)

There does not yet exist a global history that documents and examines the ways in which

disparate traditions around the world have gone about describing, analyzing, and interpreting what from their perspective is culturally alien or unfamiliar. 2 It will not come as a

surprise, then, that we are also lacking a comprehensive study discussing how different

cultural traditions have dealt with the visual art forms of other traditions, specifically in a

manner that might be called scholarly in the broadest of terms.3 Yet analyses of such intercultural or transcultural art studies would be most welcome today, now that the examination of art is developing a global perspective under the banner of “world art studies,”

4 Western Scholarship and Fang Statuary from Equatorial Africa

especially. It then becomes pertinent to ask how scholarship in various traditions worldwide has gathered knowledge on art forms from what to them are foreign cultures, in

order also that intercultural learning today might profit from examining previous endeavors in studying art across cultural boundaries. 4

The question of how students of the arts around the world have engaged with the visual

culture of traditions other than their own, leads to a whole series of subquestions. For

example, what motivated these students’ scholarly dealings with foreign art forms? In

what intellectual and sociocultural environment did they carry out their examinations?

What were their assumptions, what questions did they ask, and why? What were the

sources on which they based their analyses and what methods did they use? What did

they achieve and how have others received their results?

In this lecture, I will broach the history and intellectual contexts of one particular case of

intercultural art studies. My example concerns Western scholarly engagements with the

statuary sculpture of the Fang from equatorial Africa. How have North Atlantic scholars

approached this type of visual culture from tropical Africa? What aspects of the sculptures did they focus on? What were their frameworks of analysis and what are the intellectual roots of the perspectives they applied? I will discuss three different approaches

or paradigms in the Western study of Fang sculpture in the last half-century or so. The

term paradigm I use in a fairly loose sense of referring to a particular mental framework

that guides the scholarly approach of a given subject matter, including the conceptualization of this subject matter, the questions that are asked of it, and the methods applied to

answer these questions. The three paradigms in the study of Fang statuary I will consider

may be summarized as (i) the stylistic approach, focusing on the objects themselves and

aimed at a quantitative analysis; (ii) the culturalist approach, based on a qualitative understanding and aspiring to comprehend the sculptures in their local context of meaning and

value; and (iii) the postcolonial approach, marked by reflexivity and a shift of attention

away from the Fang to the Western appropriation of their objects. My consideration of

these three paradigms will be far from exhaustive. Rather, by briefly discussing the application of these approaches to Fang sculpture, it is my aim to introduce you to a varied

field of study that is little known in academia. Concerned as it is with the examination of

art in those cultures that have traditionally been studied by Western anthropologists, this

is a field that has been commonly known for the last three decades as the anthropology

of art.5

Western Scholarship and Fang Statuary from Equatorial Africa 5

The Fang of

Western Equatorial Africa

In western equatorial Africa today live some

one million people speaking mutually intelligible dialects of a Bantu language known as

Fang. In the anthropological literature these Fang speakers are usually divided into various subgroups, or what the older literature calls subtribes. There is no scholarly consensus about this subdivision, and some anthropologists question its relevance. Suffice it

here to say that the ways of life of more northern groups are frequently considered different enough not to include them in discussions of Fang culture generally.

Fang speakers can be found in three modern African states: in southern Cameroon,

Equatorial Guinea, and northwestern Gabon. They arrived in these parts of West Central

Africa fairly recently. According to their oral traditions, Fang groups originate in a savannah area to the northeast of their present habitat. Migrations from that area appear to

have started in the eighteenth century or earlier. These migrations may have been triggered by the military invasions and slave hunts of Fulani nomads, forcing Fang speaking

groups to seek refuge in the tropical rainforest. Practising slash and burn agriculture, Fang

lineages gradually expanded in a southwestern direction. They would reach the shores of

the Atlantic Ocean only in the early twentieth century. By that time, the Atlantic coast had

already attracted substantial numbers of Europeans and Americans for decades – traders,

hunters, explorers, abolitionists, missionaries, and finally colonialists.

Fig. 2 Fang villagers ( from: Harry Alis, “Au pays des M’Fans,” Le tour du monde LX, 1888)

The Fang make their appearance in Western writings in the second half of the nineteenth

century, when travellers ventured into the equatorial rainforest from the coast and reported on their meetings with Fang people (Fig. 2). 6 Rumoured to be cannibals by coastal

Africans, and with a reputation of fearsome warriors, the Fang nevertheless made a positive impression on some Westerners. For example, Mary H. Kingsley (1862-1900), in her

widely-read Travels in West Africa (1897), reported on having developed a special liking of

the Fang: fierce, but intelligent, courageous, and handsome.

6 Western Scholarship and Fang Statuary from Equatorial Africa

It was in the last decades of the nineteenth century also that statues, masks, and other

objects of the Fang first made their way into Europe, especially France. In the early twentieth century, Fang masks, anthropomorphic figures, and sculpted heads would attract the

attention of French artists now considered to belong to the modernist avant-garde. Thus,

in a well-known example, the Parisian painter Maurice de Vlaminck bought a Fang mask

from one of his father’s friends in 1905.7 Shortly afterwards he sold it to his colleague

André Derain, who had insisted on buying it, and who showed it to his friends Picasso

and Matisse. This now famous mask is held to have influenced the work of all four artists.

Derain later also bought other Fang sculptures, including a female figure and a carved

head. Fang masks, and especially heads and full figures became prized objects in the

private collections of a growing number of African art enthousiasts in both France and

abroad. One such figure made a huge impression when it was first exhibited in Paris in

1930 and became known as “the Black Venus.”

Western Scholarship and Fang Statuary from Equatorial Africa 7

Avant-garde artists, while inspired by the formal qualities of African sculptures, and sometimes their “magical aura,” seem to have cared little about either the meaning and role

of these objects in their original settings or indeed about their African colleagues who

created them. Although the sociocultural context of Fang masks remains understudied to

this day, already in the early twentieth century it was known that the carved heads and figures of the Fang served within the context of an ancestor cult. This is related, for example,

in the work of the German ethnographer Günter Tessmann, who lived among the Fang

for several years between 1904 and 1909. 8 In brief, the male and female statues of the

Fang, called beyima bieri, figures of the ancestor cult (sing. eyima bieri), were used to protect ancestral skulls and bones that were kept in cylindrical barrels made of bark (nsuk)

(Fig. 3). The figures are therefore also known as reliquary guardians. Anthropomorphic

heads inserted into the top of the bark barrel served the same purpose. The reliquary, to

which full figures were attached by means of a back post or projection, was placed in a

corner of the house of the leader of the ancestor cult.

Proportions and Anatomical Detail:

A Stylistic Approach to Fang Statuary

Fang statues would

become the subject of a life-long study by the French anthropologist Louis Perrois. It was

the famous prehistorian and anthropologist André Leroi-Gourhan who suggested in 1964

that his student Perrois work on the topic of Fang figures, considered “one of the mythical

gems of ‘Negro art’.”9 The idea was to first study examples of Fang sculpture available in

European collections and in publications. This would allow a close focus on the objects

themselves, which Perrois was requested to carefully look at, draw, and, if possible, touch

(Fig. 4). The second stage of the research would involve going to Gabon and study both

the creators of these statues and the figures’ place in the socioreligious life of the Fang.10

Such local and contextual art research in Africa had been pioneered by a few scholars in

the 1930s,11 and in the postwar years the prospect of gaining knowledge and insight by

doing “fieldwork” was generally perceived as the most exciting development in the study

of African art. In 1965 Perrois indeed set off for Gabon, where he would work among the

Fang and Kota, especially. He found, however, that due to the success of various religious

reform movements from the 1930s onward, the practice of producing and using Fang statues had virtually died out.12 This may explain in part why Perrois would eventually hold

on to a formal or visual analysis of the statues themselves, although he augmented his

research by what he was able to learn on site.

Fig. 3 Fang reliquaries, taken outside to be photographed, c. 1913 ( from: Karl Zimmermann, Die Grenzgebiete

Fig. 4 Fang statue, eyima bieri (Afrika Museum, Berg en Dal, Netherlands, inv. nr. 43-42;

Kameruns im Süden und im Osten. Berlin: Mittler und Sohn, 1914; photograph: Hans Gehne)

photograph: Ferry Herrebrugh)

8 Western Scholarship and Fang Statuary from Equatorial Africa

Western Scholarship and Fang Statuary from Equatorial Africa 9

This brings us to the first paradigm in the study of Fang anthropomorphic sculpture, an

approach variously known as morphological or stylistic analysis. This method implies

studying both the formal components of works of art and the combination or arrangement of these components into a visual whole. When constituent elements assume regular shape, and especially when their combination adheres to certain rules or recurring

principles of organization, one may speak of a style. Perrois follows Henri Focillion in

defining style as “un ensemble cohérent de formes,”13 a coherent or consistent assemblage of forms.

In the study of African figurative sculpture, stylistic analysis had been pioneered by the

Belgian scholar Frans Olbrechts, a Professor at Ghent University. In the late 1930s, he

had applied this type of analysis to statues from the then Belgian Congo, resulting in the

delineation of a handful of “style areas” in Central Africa, each made up of several substyles, most of them “tribal.”14 His students, including Albert Maesen, as well as other

Africanist art historians, would later refine this classification, discerning ever more styles

and clusters of styles.15 It was Maesen also who tutored Perrois in the application of stylistic analysis at the Royal Museum of Central Africa in Tervuren, near Brussels.16 Following

Olbrechts and Maesen, Perrois would concentrate in his examination of Fang sculpture

on both the proportions of figures, especially the relationships between head, torso, and

legs, and on the design of anatomical details such as eyes, ears, and mouths.

In 1972, Perrois published the results of his stylistic analysis of a corpus of some 270

statues ascribed to the Fang, most of them found in Western collections or publications

and frequently with only scant information as to their exact geographic provenance. The

majority of these objects had arrived in Europe in the decades around 1900, and Perrois

established the late nineteenth century as the time frame for his examination. The overall

aim of his analysis was to contribute in an “objective” manner – some would say a “positivistic” manner – to the nascent study of African art. Perrois conceived of this new field

of study as pertaining specifically to Africa’s bewildering variety of sculptural styles, which

he felt had hitherto been dealt with in too superficial and exploratory a manner. Detailed,

in-depth studies of the style characteristics of a given African art form, here Fang figurative sculpture, would mark the beginning of what he saw as a truly scientific approach to

African art.17

Perrois proposed that there are two stylistic regions among the Fang, a northern one,

made up of elongated figures (longiform) and showing highly stylized anatomical details,

and a southern one, consisting of more stocky statues (breviform) and a tendency to more

naturalism in the rendering of body parts. These two style areas he then divided further

10 Western Scholarship and Fang Statuary from Equatorial Africa

into substyles, two for the northern region and four for the southern one.18 These substyles, he suggested, coincide with “subtribal” divisions among the Fang (Ntumu, Okak,

Betsi, etc.).

Perrois’s proposals have been severely criticized by the anthropologist James Fernandez

and his wife Renate, who worked among the Fang at the end of the 1950s.19 The

Fernandezes argue, among many other things, that Perrois seriously underestimates the

intergroup mobility of individuals among the Fang, making it hard to pinpoint the “subethnic” identity of sculptors and their work. They also demonstrate that individual Fang

carvers produced statues in varying styles that on the basis of Perrois’s analysis would

have to be ascribed to disparate so-called subtribes.

Time does not allow me to delve much deeper into the characteristics and scholarly value

of the stylistic approach, or the style area paradigm in the study of so-called tribal art more

generally. 20 But let me briefly point to a few topics that need further elaboration in view of

this paradigm’s intellectual history. First, although Africanist art scholars like Perrois fail

to mention this, the morphological and style area approach had already been applied to

the art of New Guinea as early as the late nineteenth century. In the field of Melanesian

art studies, this approach would prove popular for almost a century. 21 Interestingly, the

first scholar to adopt a style area approach to New Guinea, Alfred C. Haddon, had trained

as a zoologist. 22 To his mind, he was applying to the realm of art the same taxonomical

approach he was used to in zoology. 23 The intellectual roots of stylistic classifications in

the study of the art of small-scale societies outside the West are thus not limited to the

field of art history, with which the examination of style is usually associated, 24 or archaeology, where stylistic and related typological analyses seem equally common.

Haddon’s taxonomical approach also leads us to another topic. It has been suggested

that, growing out of a more general nineteenth-century desire to provide “visual encyclopedic inventories” of the world, its peoples, and their products, the practice of classification became a tool for imperial and colonial ambitions, allowing for surveillance and control over subjected peoples. 25 Along the same lines, postcolonial analysis often considers

the subdivision of African and other populations into “tribes” or ethnic groups a colonial

invention facilitating administration and control. Being inherently classificatory, stylistic

analyses and especially style area approaches could then perhaps be construed as rooted

in a nineteenth-century Western tendency to map the world and to attempt to at least

symbolically master it, as one possible line of historical investigation among others. 26

Western Scholarship and Fang Statuary from Equatorial Africa 11

From a more pragmatic point of view, one may note, finally, that stylistic approaches seem

especially popular in cases where data other than the objects themselves are lacking or

sparse, because these data are no longer, or not yet, available. Be this as it may, in the

study of African art we see that the style paradigm becomes less prominent when, increasingly in the decades after the Second World War, anthropologists and art historians start

to carry out local research on African cultures and their visual arts. These scholars tended

to shift attention from style to studying the sociocultural contexts of these arts. Indeed,

although the Fang case discussed so far might suggest otherwise, these researchers more

often than not found indigenous art traditions alive and well, as some do up to this day,

allowing them to examine the creation, use, function, and meaning of art on site.

Form and Value:

A Culturalist Approach to Fang Statuary

One such

researcher is James Fernandez, who spent some eighteen months among the Fang

between 1958 and 1960. His main focus of attention was Bwiti, a syncretist cult combining African religious views and practices with elements of Christianity. 27 Fernandez also

showed great interest, however, in Fang art, artists, and aesthetics, devoting several studies to these topics, especially in the early years of his publishing career. Whereas Perrois

opts for a quantitative approach to Fang sculpture, Fernandez elaborates a qualitative perspective. His emphasis is on understanding how the Fang experience their statues and

other forms of expressive culture against the background of the Fang value system.

Fernandez is a student of the American anthropologist Melville Herskovits. Herskovits

himself was trained by the German-born scholar Franz Boas, generally regarded as the

founder of American anthropology. Boas was greatly interested in art, and encouraged

his students to take into account artistic objects and their creators when doing on-site

research. Indeed, Boas was among those who in the early twentieth century promoted

so-called fieldwork as a methodological prerequisite in anthropological research. Through

this procedure, investigators would get to know a culture “from within.” The ideal was to

describe a given culture in and on its own terms, to elucidate the “native’s point of view.”

In the Boasian tradition that developed in the USA, emphasis was placed on a culture’s

myths, beliefs, and values, rather than, say, its kinship system or economy, even though a

neat division between these domains does not seem possible. In addition, these ideational dimensions of culture were held to be reflected in a culture’s art forms. 28 The “world

view” that these art forms were understood to express, moreover, was seen as unique to

given culture, a distinctive product resulting from local historical processes, like the rest

of culture. It is this historical particularism, and especially the resulting stance known as

cultural relativism, that Boas and his school became best known for.

12 Western Scholarship and Fang Statuary from Equatorial Africa

Most of Boas’s students carried out research in Native American societies, but some

adopted his approach and thematic emphases in studying cultures in other parts of the

world. One such student was Herskovits. A champion of cultural relativism, Herskovits

would focus his attention on Africa, and the African diaspora, devoting a substantial part

of his research to the visual arts, among both the Fon in present-day Benin and the socalled Maroons of Suriname. 29 Although one has to be careful in drawing up intellectual

genealogies, against this background it does not come as a surprise that Herskovits’s student30 Fernandez was to pay considerable attention to the arts and their embeddedness in

the local universe of values among the Fang.31

In an early publication, Fernandez addresses the question of what counts as aesthetically pleasing among the Fang.32 Interestingly, in dealing with this question he considers

a whole range of phenomena in Fang life, including village layout, notions of personhood,

and even social organization. He begins his analysis, however, with Fang aesthetic evaluations of their anthropomorphic statues. Indeed, Fernandez found both practising sculptors and audiences still in touch with the creation, use, and function of reliquary guardians. When asked to assess the visual qualities of these sculptures, Fang critics talked

about the balance that a figure should display. Specifically, they stated that there had to be

an equilibrium between the left and the right parts of the statue, whether arms, legs, eyes,

breasts, or shoulders. Without this balance between opposite body members, they said,

the figure would lack vitality. And it is this vitality that the Fang appreciate aesthetically,

argues Fernandez, whether in sculpture, music, dance, or various other cultural phenomena.

One question that arises is: How can the balance between opposite body members,

meaning their symmetrical rendering, generate the desired quality of vitality in a statue?33

In order to answer this question, we have to consider the way in which the Fang, according to Fernandez, conceptualize the idea of vitality.34 For that purpose, we have to go

beyond Fernandez’s essay on aesthetics and take into account his other work on the Fang,

especially his extensive Bwiti, a study of more than 600 pages that may be considered

Fernandez’s ethnography of the Fang.35

Vitality is Fernandez’s translation of the Fang concept ening. This concept, he says, can

also be interpreted as “life” or “the capacity and determination to survive.” It is the quality

that is strived for in all areas of Fang life, including Bwiti. The traditional Fang emphasis

on vitality can be understood in light of both the hardships of their migratory history and

the subsequent turmoil caused by colonization and missionary activities. Now ening or

vitality is thought to arise when two complementary opposites are brought together into a

Western Scholarship and Fang Statuary from Equatorial Africa 13

balanced relationship. This balance or equilibrium the Fang refer to as bipwé. The contrastive yet complementary elements that need to be balanced are essentially those of maleness and femaleness, and of qualities associated herewith. Male qualities include activity,

willfulness, and determination, whereas female qualities comprise reflection, deliberation,

and thoughtfulness. Although these qualities are gendered, they do not exclusively belong

to males or females, respectively. Moreover, they can also be found in phenomena other

than human beings, for example social life in the village or the Bwiti cult. Male qualities may be summed up by the term elulua, meaning appropriate activity or pleasurable

animation; female qualities are encapsulated by the term mvwaa, tranquility and evenhandedness.

ated with the female qualities of reflection and thoughtful direction. In human beings, it

is hoped that these contrastive but complementary forces work together harmoniously

in order to produce proper action. Now in statues we usually see a muscular torso that,

together with the posture of the arms, suggests strength and determination. Contrasting

this, the face often appears to expresses composure and reflection. It is as if the female

qualities of calmness and thoughtfulness control and direct the potentially unbridled and

destructive male energy that seems about to be released. In this manner, too, statues

seem to balance male and female qualities, thus giving them vitality (Fig. 5).38

The Fang value both male and female qualities, with some contexts requiring so-called

female modes of behaving, whereas others call for male types of action. The generation

of vitality, however, requires the balanced presence of both. Moreover, such an equilibrated relationship ensures that neither male nor female qualities take excessive and hence

undesirable forms. Indeed, the Fang recognize both excess of activity and excess of tranquility. Thus, people or situations can progress from elulua into the state of ebiran, where

over-active behavior leads to destruction and social disorder. Similarly, from mvwaa one

may depart into the condition of atek, docility, laziness, or lethargy. In an equilibrated relationship between male and female qualities, in contrast, such excesses are avoided, since

one set of values counterbalances the other, thus preventing it from going to extremes.

With male and female qualities thus preserved in pristine form, their equilibrated relationship at the same time creates the conditions for the emergence of vitality.

Against this background we may return to the Fang evaluation of statues and the idea that

vitality is brought about by the balance of opposite body members. Now the symmetrical

rendering of a human body creates an equilibrium of spatial opposites. Vitality, however,

is said to arise from the balance of contradictory yet complementary oppositions. The

mere formal or visual opposition of body members thus does not seem to suffice to produce ening. It therefore needs pointing out that in other contexts Fernandez observes that

for the Fang the left side of the human body (efa meyal) counts as female, whereas the

right side (efa meyom) is regarded as male.36 A symmetrical statue may thus indeed be

said to balance opposing yet complementary qualities, and to generate vitality as a result.

Fang statues, moreover, seem to unite male and female qualities also in another way.37

In this respect it needs observing that the Fang regard the torso of a human body as

the repository of energy and power. The torso may therefore be associated with the male

qualities of activity and vigour. The head, on the other hand, is considered the body part

that controls and directs the power residing in the torso. The head may thus be associ14 Western Scholarship and Fang Statuary from Equatorial Africa

Fig. 5 Fang statue, eyima bieri (Afrika Museum, Berg en Dal, Netherlands, inv. nr. 13-45;

photograph: Ferry Herrebrugh)

In the type of analysis presented just now, Fang aesthetic preference in sculpture is

explained entirely with reference to the Fang universe of values, seen as the unique product of Fang culture and its history. Such an approach where culture is explained exclusively in terms of culture is sometimes referred to as culturalist. In its most extreme form,

it is an approach that presupposes that human beings are born with a blank slate, a tabula

rasa that enculturation will inscribe with culturally relevant and indeed relative meaning. In anthropological practice, it is then up to outside scholars to delve deeply into a

given culture in order to gain an intersubjective understanding of that culture, albeit it

one based on as many empirical data as possible. When trying to account for a particular

cultural phenomenon, such as aesthetic preference, attention is drawn to other cultural

phenomena, such as the local value system. In Boasian as well as many other forms of

Western Scholarship and Fang Statuary from Equatorial Africa 15

anthropology, this culturalist and to some extent hermeneutic approach is so much taken

for granted that it seems hardly to require a label.

The culturalist paradigm, however, does not provide the only approach to understanding

cultural phenomena. It also does not offer the only explanatory approach to aesthetic

preference. In view of the latter, it may have occurred to you that the Fang preference for

symmetry in sculpture, when stripped off its cultural associations, is not all that exotic or

remarkable. Indeed, intercultural comparative analyses suggest that symmetry is an aesthetic universal. If all human beings appreciate visual symmetry, then it becomes tempting to explore the possibilities of applying not a culturalist but a naturalist approach to

this preference. Such a naturalist approach draws attention to the biological heritage of

human beings, who are conceived, like all other living organisms, as products of bioevolutionary processes. It is an approach that assumes that humans are born with innate

tendencies and indeed preferences. One such well-documented preference concerns the

symmetry of the human body. It is argued that there are good evolutionary reasons why

this preference has become innate, reasons having to do with symmetry of the body being

an index of health and thus an important factor in mate choice. 39 The perceptual bias for

bodily symmetry, as it is called, can then be easily seen at work in the evaluation of carved

human bodies as well.

One other explanatory option, finally, concerns an approach that, while basically naturalist, might be situated in between a purely culturalist and a purely naturalist perspective. I

am referring to the so-called embodied cognition approach. Briefly, in an embodied cognition approach it is argued that our ways of thinking and making sense of the world are

fundamentally based on our bodily experiences. These experiences are thus held to structure on a basic level the way we conceptualize the world and give meaning to it. One such

experience is the sensation of bodily balance, a sensori-motor equilibrium that we learn

to achieve early in life and which we foster ever after. 40 Applied to the Fang case, one may

then ask: Could it be that the fundamental and positive experience of bodily equilibrium

forms the basis of a system of meaning and value that is founded on this very experience

of balance, now used metaphorically to articulate a desired state of being? Put differently,

might we be dealing with a world view that, while taking into account a variety of contextual factors, is a mental elaboration that ultimately stems from a fundamental bodily

experience?

These interdisciplinary musings, inspired by fairly recent developments in evolutionary

theory and cognitive science, are far removed from the world of African art studies, which

is thoroughly culturalist, or if you like, social-constructivist. This holds not only for the

16 Western Scholarship and Fang Statuary from Equatorial Africa

anthropologists involved in this field, but also for art historians specializing in African art.

Most of them have adopted the methods and interpretive procedures of anthropologists,

especially those of Boasian anthropologists like Fernandez. The “semantic contextualism”

that these anthropologists propound in fact chimes well with the iconological approach

developed by the art historian Erwin Panofsky, an approach on which many Africanist art

scholars in the second half of the twentieth century are likely to have been fed. Like the

Boasians, and equally influenced by the tradition of German Idealism, it seems, Panofsky

suggested to contextualize works of art, in his case European art, against the background

of a culture or period’s systems of thought and value. 41

Appropriation and Value Creation:

A Postcolonial Approach to Fang Statuary

One art historian who has applied this Boasian and Panofskian approach to the study of African art

is the American scholar Susan Vogel. Specifically, she has used this approach in studying

the sculpture of the Baule of Côte d’Ivoire. In a way similar to Fernandez, Vogel argues

that Baule aesthetic preferences in sculpture can be explained by reference to the sociocultural values of this people. 42 Here I will not dwell on Vogel’s research among the Baule,

but will be concerned instead with one of her later projects, one that provides the third

and final approach to Fang sculpture to be discussed this afternoon.

In the late 1990s, after a distinguished career as a researcher, curator, and museum director, Vogel went back to school and trained as a filmmaker at New York University. For

her graduate film she wrote and directed Fang: An Epic Journey. The film, which mixes

documentary and fiction techniques, was produced in 2001 and released the following

year. 43 In this speedy, eight-minute production, Vogel narrates the fictional “life history”

of a Fang statue, after it had left its original context of use in Africa in the early twentieth

century. 44 The intellectual framework of Vogel’s production can be characterized as that of

postcolonial reflexivity, enhanced by various other postmodern themes. Before elucidating this context somewhat more, let me first sketch the contents of the film.

The opening scenes bring the viewer to New York in 1970. A scholar is sitting in his study,

with a statue identifiable as Fang standing on his desk. The Fang figure appears to be in

the possession of a woman who has lent the statue to the scholar for the purposes of a

book he is writing. She requests him in a letter to return the figure, now that his book is

about to be finished, for she has agreed to lend the sculpture to an exhibition that will tour

various European cities.

Western Scholarship and Fang Statuary from Equatorial Africa 17

A flashback then transports us to Cameroon in 1904. A figure in colonial dress, based on

the ethnographer Tessmann, is sitting at a table adding an inventory number to a Fang

statue in front of him. The colonial authorities, we are informed, have recently confiscated

both the “idol,” as the object is called, and its bark barrel, violently destroying in the process the shrine in which the reliquary had been placed. The Tessmann-like character says

he is still looking for evidence of cannibalism among the Fang, and complains that the

natives are cunningly hiding everything.

In the next scene, the feathered figure, now referred to as a “cannibal doll,” is offered for

sale to a shopkeeper in Paris, together with its bark barrel. The shopkeeper agrees to buy

the statue but not the barrel. This character, inspired by the young Paul Guillaume, who

would later become a famous dealer of African sculpture, refers to the object as a “fertility god.” We remain in Paris, it is now 1907, and we see an artist at work in a room that

reminds one of the studio of the Cubist painter Georges Braque, as shown in a photograph of 1911. The artist is struggling to make sense of the visual composition of the Fang

statue, which he unsuccessfully tries to render on canvas. He calls the statue a “fetish.”

Ten years later the Fang sculpture surfaces at a sales exhibition in Paris. It is labelled

“Primitive idol (19th cent.)” and is offered to buyers for 500 francs. Visual cues in the film

suggest that African sculpture is in ever-larger circles no longer seen as an exotic curiosity

but as a form of art, one that anticipated the avant-garde art produced in Europe at the

time. We then see someone tampering with the Fang figure, apparently in order to accommodate it to the prevailing taste of Western collectors. The statue’s penis is removed, 45

as are the metal rings around its neck. The figure, which has long since lost its feathers,

is thus made to look more like a “pure sculpture,” as appreciated by modern art lovers.

Moreover, the light-colored statue is blackened by what seems to be shoe polish. Thus

transformed, it is again put up for sale. Now called “African sculpture (13th century),” its

price has risen to 300,000 francs.

The scene then shifts to Berlin in 1933. We see a depressed German scholar hanging in

his chair. A student of African kinship systems, he had bought the Fang figure some time

before because he felt it testified well to the shared humanity among the world’s peoples.

The anthropologist calls the figure an “ancestor statue.” He remembers the day the surrealist photographer Man Ray had visited him and taken pictures of the sculpture. A new

age of intercultural understanding seemed to have dawned. But how different things look

today. He fears that the Nazis will confiscate both the book manuscript he is working on

and his collection of “African art,” as he calls it. The anthropologist, in whom we recognize Julius Lips, 46 has therefore decided to take drastic measures to save his favorite

sculpture. He saws it in half47 and sends the two pieces separately to friends abroad.

18 Western Scholarship and Fang Statuary from Equatorial Africa

New York, 1948. A posh-looking woman living in an elegant apartment has inherited the

top half of the Fang sculpture. She begins a correspondence with Dr. Locke, the African art

specialist whom the viewer has met in the opening scenes. It soon becomes clear to her

that the Fang figure is incomplete and she starts a search for the missing half. One day a

package arrives containing a lamp whose base consists of the lower half of the statue. The

figure now complete again, it will later feature in Dr. Locke’s book.

According to the booklet accompanying the film, the Dr. Locke character is based on the

African-American philosopher and patron of the arts Alain Locke (1885-1965). The female

owner of the Fang figure, who has apparently stayed in touch with Locke ever since her

first request for information, is said to be inspired on the socialite and political activist

Nancy Cunard (1891-1965). 48 Towards the end of the film, we see her host the official presentation of Dr. Locke’s book, whose discussion of African creativity she feels will contribute to solving the “race problem in America.” The film ends by suggesting that the Fang

figure, having made its European tour, will be donated to a New York art museum, seen as

its “final home.”

Asked to comment on this production prior to its release, Africanist art historian Jean

Borgatti sighed that the film addresses in eight minutes what would take her two lectures to cover. 49 Vogel’s film indeed takes up a host of subjects, most of them topical.

Specifically, the film considers a range of object-related issues that became the focus of

much attention in the social sciences and humanities at the end of the twentieth century, issues that are still with us today. Central among these in the present context is

the so-called social life of things, or the life histories of objects, a theme initiated by a

volume edited by Arjun Appadurai in 1986.50 It is argued that throughout its existence an

object changes contexts, and that each change of context is accompanied by shifts in the

meaning and value ascribed to the object. It was soon realized that this line of reasoning

could profitably be applied to the “cultural biographies” of objects that had arrived in

Europe and America from colonized areas outside the West. Much attention focused on

the acquisition itself of objects within the context of Western colonialism. In the second

half of the 1990s and the early years of the twenty-first century, this led, for example, to

a whole series of edited volumes on the topic of colonial collecting. 51 One key concept in

this connection has since become a household term in critical scholarship: appropriation,

or making one’s own, usually employed with negative overtones of illegitimacy and indeed

moral disapproval.

Western Scholarship and Fang Statuary from Equatorial Africa 19

Once they had arrived in the West, objects, especially figurative objects, were variously

categorized, as Vogel’s film illustrates. They were labelled idols or fetishes, and eventually

sculptures and works of art. If the collecting and subsequent ownership of these objects

could be called “material appropriation” – admittedly a rather thin characterization that

leaves out symbolic dimensions – then this labelling of objects against the background

of Western analytical categories might count as “conceptual appropriation.” A third type

of appropriation addressed in Vogel’s film is “artistic appropriation,” as evidenced by

the allusions to Cubist painters and the work of the photographer Man Ray, inspired by

or incorporating African works of art. Finally, there are suggestions of “scholarly” and

“museological” appropriation, since the Fang statue in the film ends up featuring in both

a learned book and a museum. Issues of appropriation in turn evoke the much-discussed

topics of power and authority, exercised by those involved in the various types of appropriation mentioned.

The booklet edited by Vogel and published together with the film is titled Idol Becomes Art!

This suggests that for Vogel the changes in the statue’s classificatory meaning and the

accompanying shifts in value, including monetary value, are themes central to the film.

This corresponds well with a Marxist-inspired postmodern emphasis on commodification

and value creation. Indeed, objects arriving and journeying in the West are frequently analyzed as items that have exchange value within the international market systems in which

they tend to circulate, notably art markets. This framework of analysis also lends itself

well to raise yet another favorite topic of recent scholarship, namely authenticity, seen as

a mere social construction, not an essential quality. 52 In Vogel’s film the topic of authenticity is addressed in a rather straightforward manner by reference to the removal of the

bark barrel, feathers, metal rings, and other accoutrements of the statue. These material

changes, also including the blackening of the object, are in turn related to processes of

value creation in the art market.

The Western elite taste that the art market caters for is one of several other topics that

Vogel’s film broaches. The film might also be interpreted as raising such issues as unequal

power relations in colonial situations, cultural property, the ethics of representation, restitution, and more. In sum, it is easy to symphatize with Borgatti’s sigh.

Yet, at the same time, one may also wonder how many lectures it would take to properly

introduce all the dimensions of Fang sculpture that the film does not address. For, however much all the film’s varied topics have been foregrounded as of critical value to postmodern and postcolonial analysis, and however much these topics continue to demand

scholars’ attention,53 their discussion appears to have almost completely replaced any

20 Western Scholarship and Fang Statuary from Equatorial Africa

consideration or even interest in the beliefs, values, and assessments of the people who

produced and used these objects in the first place. Thus, of the creation, deployment,

function, or evaluation of Fang statues in their original cultural setting we learn nothing in

Vogel’s film.54 Indeed, there must be a whole generation of scholars by now who think that

the anthropology of art is basically about colonial appropriation, representation of the

Other, and the role of artistic objects as commodities in globalized art markets.

Envoy Ladies and gentlemen, taking the Fang as my case study, in this lecture I have

tried to give you some idea of the varied ways in which Western scholars in the last halfcentury have approached the visual art of small-scale cultures outside the West. I have

also briefly suggested how disciplines outside the humanities might provide us with fresh

perspectives on the empirical data that scholars have gathered on art and aesthetics in

these cultures. My survey of approaches is not nearly complete and could be extended further back in time, taking into account evolutionist, diffusionist, and functionalist perspectives on art, as developed by anthropologists and art scholars between, say, the 1880s

and the 1950s. Indeed, it is my intention as holder of this extraordinary chair to further the

research into the history of the Western scholarly reception of the art of small-scale societies from outside Europe. Specifically, I intend to focus on the late nineteenth century,

the period when the art forms of these cultures were first systematically incorporated into

Western scholarship. It is hoped that a focus on the early days of studying these arts will

shed light on later developments as well, if only since later efforts tend to respond to former endeavors. Apart from the logically inspired desire to start at the beginning, another

source of inspiration for these plans consists of an interesting body of scholarly work that

has recently come to my attention through a form of serendipity.55 I have learned from

this work that the end of the nineteenth century holds quite a few surprises for someone

like myself who was brought up academically to view this period in the study of the art of

small-scale societies as hopelessly marred by racism, colonialism, and sociocultural evolutionism. Although the influence of these -isms is at times indeed discernible to varying

extents, they do not all appear as dominant in the contemporary literature as most later

commentators would have us believe. Specifically, these commentators ignore the cosmopolitan approaches of scholars who were eager to consider the art of the whole world in

examining the artistic and aesthetic dimensions of being human. Some revisionism of this

intellectually exciting period thus seems in order. I am therefore glad to announce that I

have been able to team up with my new Tilburg colleague Kathryn Brown in organizing a

conference that will include attention to nineteenth-century Western dealings with artistic

objects from around the world.

Western Scholarship and Fang Statuary from Equatorial Africa 21

To the Treub Foundation for Scientific Research in the Tropics I express my sincere gratitude for their willingness to establish an extraordinary chair devoted to the examination

of art forms that Western academia tends to neglect. In considering this neglect, we need

not only take into account that these art forms were produced in cultures outside the

European tradition; we also have to consider that they originate in regions of the world

that, unlike some other regions outside the West, presently cannot usually afford the

establishment of university chairs to promote the research of their artistic heritage. My

thanks therefore extends to Tilburg University’s Faculty of Humanities, whose Dean Arie

de Ruijter, an anthropologist, showed no hesitation in giving this new chair an institutional home. Behind the scenes, my good colleague Raymond Corbey has been instrumental

in bringing all parties together. Ray, I can only hope that I will prove worthy of the trust

that you, the Treub Foundation, and Tilburg University have put in me.

Ik heb gezegd.

Notes

22 Western Scholarship and Fang Statuary from Equatorial Africa

Western Scholarship and Fang Statuary from Equatorial Africa 23

1

Felipe Fernández-Armesto, Pathfinders: A Global History of Exploration (New York: W. W.

Norton, 2006).

8

Günter Tessmann, Die Pangwe: Völkerkundliche Monographie eines westafrikanischen

Negerstammes (Berlin: Ernst Wasmuth, 1913; reprinted by Johnson Reprint Corporation, New York,

1972, with a new “Geleitwort des Verfassers zu seiner Pangwe-Monographie”), I: 275; II: 116ff.

2

But see Siep Stuurman, De uitvinding van de mensheid. Korte wereldgeschiedenis van het denken

over gelijkheid en cultuurverschil (Amsterdam: Bert Bakker, 2009), a study that focuses on how vari-

9

ous traditions of thought around the world (especially Judaism, Christianity, Islam, and Greek and

statuaire faη, Gabon (Paris: ORSTOM, 1972), p. 9, n. 2.

Louis Perrois, Visions of Africa: Fang (Milan: 5 Continents Press, 2006), p. 7. See also Perrois, La

Chinese philosophy) have dealt with people outside their own circles in terms of their “humanity.”

10

3

Perrois, Visions of Africa: Fang, p. 8.

To be clear, I am not having in mind the influence that distinct visual art traditions have exer-

cised on the art forms of other traditions, although this “artistic convergence,” if you like, is to

11

Hans Himmelheber, Marcel Griaule, P. Jan Vandenhoute, and Albert Maesen, among others.

varying degrees often part of the encounter between cultures. Indeed, my Leiden colleague Kitty

Zijlmans and I are promoting examinations of this phenomenon under the heading of “intercultur-

12

alization in art,” conceived as one major subject of analysis within the new field of world art stud-

l’art faη est un art disparu, ou plutôt mort ….” (Perrois, La statuaire faη, p. 9; see also p. 12, and

ies. See World Art Studies: Exploring Concepts and Approaches ed. Kitty Zijlmans and Wilfried van

Visions of Africa: Fang, p. 9). For a recent discussion of the reasons for the demise of Fang anthro-

Damme (Amsterdam: Valiz, 2008).

pomorphic sculpture, see Jessica Levin Martinez, “Ephemeral Fang Reliquaries: A Post-History,”

“les ‘byéri’ faη ne sont presque plus utilisés de nos jours, on ne les trouve que dans les musées;

African Arts 43.1 (2010), pp. 32-33. The main argument of Martinez’s essay, for that matter, is that

4

For more on this topic, see Wilfried van Damme, “‘Good to Think’: The Historiography of

the memory of Fang statues lives on in various ways in Gabon to this day.

Intercultural Art Studies,” World Art 1.1 (2011): 53-69.

13

Perrois, La statuaire faη, pp. 7-8.

5 For a more extensive analysis of the history of the label “anthropology of art,” and its various interpretations, see Wilfried van Damme, “Anthropologies of Art,” International Journal

14

of Anthropology 18.4 (2003): 231-44; reprinted in adapted form as “Anthropologies of Art: Three

manuscript of this book was finished in 1940, but the Second World War delayed its publication. A

See Frans M. Olbrechts, Plastiek van Kongo (Antwerpen: Standaard Boekhandel, 1945). The

Approaches,” in Exploring World Art, ed. Eric Venbrux, Pamela Rossi, and Robert L. Welsh, pp.

French edition was published in 1959 (Les arts plastiques du Congo belge (Brussels: Erasme; transla-

69-81 (Long Grove: Waveland Press, 2006). See also, for example, The Anthropology of Art, ed.

tion A Gillès de Pélichy). For summaries and discussions of Olbrechts’s morphological and style

Howard Morphy and Morgan Perkins (London: Blackwell, 2006).

area approach, see Daniel Crowley, “Stylistic Analysis of African Art: A Reassessment of Olbrechts’

‘Belgian Method’,” African Arts 9.2 (1976): 43-49, and Constantine Petridis, “Olbrechts and the

6

For more elaborate discussions of these “first contact” situations, see James W. Fernandez,

Bwiti: An Ethnography of the Religious Imagination in Africa (Princeton: Princeton University Press,

Morphological Approach to African Sculptural Art,” in Frans M. Olbrechts: In Search of Art in Africa,

ed. Constantine Petridis, pp. 119-40 (Antwerp: Etnografisch Museum, 2001).

1982), pp. 29ff., and Xavier Cadet, Histoire des Fang, peuple gabonais. Les Tropiques entre mythe

et réalité (Paris: L’Harmattan, 2009). Louis Perrois describes the Western acquaintance with and

15

collecting of objects in western equatorial Africa from the 1850s to the 1930s in “The Western

“‘A Remarkable Exhibition in the City Festival Hall’: Congolese Art in Antwerp (1937-38),” in Frans

Historiography of African Reliquary Sculpture,” in Eternal Ancestors: The Art of Central African

M. Olbrechts: In Search of Art in Africa, pp. 177ff.

See Petridis, “Olbrechts and the Morphological Approach to African Sculptural Art,” and idem

Reliquary, ed. Alissa LaGamma, pp. 63-77 (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art / New Haven:

Yale University Press, 2007).

16

Perrois, Visions of Africa: Fang, p. 8. Perrois also notes that his mentor Leroi-Gourhan was him-

self pursuing stylistic analysis at this time, focusing on Paleolithic cave paintings in Europe.

7

See, for example, Ben-Ami Scharfstein, Art Without Borders: A Philosophical Exploration of Art

and Humanity (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), p. 279.

24 Western Scholarship and Fang Statuary from Equatorial Africa

17

Perrois, La statuaire faη, pp. 7-8.

Western Scholarship and Fang Statuary from Equatorial Africa 25

18

Although he has since made a few modifications, Perrois, having by now extended his corpus to

25

Raymond Corbey, “Natuurlijke historie als exploratie en exploitatie,” in De exotische mens.

some 1000 works, basically retains his classification of Fang statuary (see Perrois, Visions of Africa:

Andere culturen als amusement, ed. Patrick Allegaert and Bert Sliggers, pp. 67-75 (Tielt: Lannoo,

Fang).

2009).

19

26

James W. Fernandez and Renate L. Fernandez, “Fang Reliquary Art: Its Quantities and

From what I know, and perhaps not surprisingly, no scholar involved in style area approaches

Qualities,” Cahiers d’Etudes africaines 25.4 (1975): 723-46. Sydney Kasfir, “One Tribe, One Style?

mentions this as a motivation for their efforts (as anthropologists might say, their emic motivations

Paradigms in the Historiography of African Art,” History in Africa 11 (1984): 163-93, has criticized

do not correspond to the incentives suggested by etic analyses). Rather, one usually states as one’s

the tendency among Africanist art scholars to equate “styles” with “tribes” more generally, point-

aim the attribution of previously nonclassified objects in space, and possibly time, thus also intro-

ing, for example, to the ahistorical character of this approach.

ducing attempts at reconstructing cultural history through objects as one possible goal of stylistic

analyses in scholarship; for the latter, see, for example, Carl A. Schmitz, “Style Provinces and Style

20

For a reappraisal of style studies in the anthropology of art, see Pieter ter Keurs, “The Return

Elements: A Study in Method,” Mankind 5.3 (1956): 107-16.

of Style Analysis: A New Exploration of an Old Subject,” in Framing Indonesian Realities: Essays in

Symbolic Anthropology in Honour of Reimar Schefold, ed. Peter J.M. Nas, Gerard A. Persoon, and

27

See Fernandez, Bwiti.

Rivke Jaffe, pp. 161-76 (Leiden: KITLV Press, 2003).

28

21

The most extensive example is Reimar Schefold, Versuch einer Stilanalyse der Aufhängehaken

vom Mittleren Sepik in Neu Guinea (Basel: Pharon Verlag, 1966).

For Boas and his school, as Paula Girshick has suggested, art was seen as “an expression of the

deepest cultural values” (“Envisioning Art Worlds: New Directions in the Anthropology of Art,” in

World Art Studies: Exploring Concepts and Approaches, p. 219). The idea that the visual arts reflect

or embody a culture’s mind-set had already been suggested by various eighteenth- and nineteenth-

22

Alfred C. Haddon, The Decorative Art of British New Guinea (Dublin: Royal Irish Academy,

century scholars in Germany and elsewhere, including not only Herder and Hegel but also Boas’s

1894). See also his Evolution in Art, As Illustrated by the Life-Histories of Designs (London: Walter

mentor in anthropology, Adolf Bastian, who regarded artistic objects as the “incarnations of folk

Scott, 1895). Another early study is Konrad T. Preuss, “Künstlerische Darstellungen aus Kaiser-

ideas,” and even the “sole imprints” of a people’s “folk spirit” (as cited by Paola Ivanov, “‘… to

Wilhelmsland in ihrer Bedeutung für die Ethnologie,” Zeitschrift für Ethnologie 29 (1897): 77-139.

observe fresh life and save ethnic imprints of it.’ Bastian and Collecting Activities in Africa During

the 19th and Early 20th Centuries,” in Adolf Bastian and the Universal Archive of Humanity: The

23

This is in itself in accordance with the scientific rather than scholarly approach that the first

two generations of anthropologists in the second half of the nineteenth century followed in their

Origins of German Anthropology, ed. Manuela Fischer, Peter Bolz, and Susan Kamel, pp. 238, 239

(Hildesheim: Georg Holms Verlag, 2007)).

studies of extra-European societies, including their material culture and art. Indeed, anthropology being to a large extent a museum-based science in those early years, its practitioners often

29

focused on objects, seen as the hard, scientific evidence on which to base the analysis of culture.

17 (1930): 25-37, 48-49, dealing with the arts of the Maroons, descendants of enslaved Africans in

See, for example, Frances Larson, “Anthropology as Comparative Anatomy? Reflecting on the Study

Suriname. For a survey and analysis of Herkovits’s writings on the arts of the Fon, see Suzanne P.

of Material Culture During the Late 1880s and the Late 1900s,” Journal of Material Culture 12.1

Blier, “Melville J. Herskovits and the Arts of Ancient Dahomey,” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 16

(2007): 89-112, for British anthropology, and H. Glenn Penny, Objects of Culture: Ethnology and

(1988): 125-42.

See, for example, Melville J. Herkovits and Frances S. Herskovits, “Bush-Negro Art,” The Arts

Ethnographic Museums in Imperial Germany (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002)

for German anthropology.

30

Many of Herkovits’s students would devote attention to visual art and artists in African cul-

tures, including William Bascom, Justine M. Cordwell, Daniel J. Crowley, Warren L. d’Azevedo,

24

As an interesting aside, it has been suggested that the emphasis on style in African art stud-

John C. Messenger, Simon Ottenberg, and James H. Vaughan. With the exception of Cordwell and

ies has until the 1960s served as a way of making African sculpture acceptable as a subject for

Ottenberg, all these scholars, also including Fernandez, contributed to the volume The Traditional

the discipline of art history, characterized at the time by stylistic analysis, under the influence in

Artist in African Societies, ed. Warren L. d’Azevedo (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1973;

part of modernist formalism. See Marie-Jeanne Adams, “African Visual Arts from an Art Historical

reprint 1989, with a new Preface). The volume, which is still the most comprehensive of its kind

Perspective,” African Studies Review 32.2 (1989), p. 56.

26 Western Scholarship and Fang Statuary from Equatorial Africa

Western Scholarship and Fang Statuary from Equatorial Africa 27

today, is dedicated to Herskovits “for whom individual creativity was the essence of humanity, and

recognized by the Fang as a source of a statue’s quality. For more details, see Fernandez, “Principles

who persistently urged his students and colleagues to discover the art in culture.”

of Opposition and Vitality,” p. 59 (reprint pp. 365-66).

31

39

Fernandez (1982: xx) relates that it was Herskovits “who focused my African interests on reli-

See, for example, Wilfried van Damme, “World Aesthetics: Biology, Culture, and Reflection,”

gion and it was he, out of his … pronounced relativism, who initiated my interest in the ‘creation of

in Compression vs. Expression: Containing and Explaining the World’s Art, ed. John Onians

cultural realities’.” Fernandez also mentions that “To me the best work in anthropology has been

(Williamstown: Clark Art Institute, 2006), pp. 164, 168-69.

done, to speak only of a generation or age grade now passed on, by Malinowski, Ruth Benedict, E.E.

Evans Pritchard, Marcel Griaule, and Clyde Kluckhohn” – not so much because of the theoretical

40

perspectives their works propound but because of “their embeddedness in the local idiom, their

and Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), esp. pp. 163-64, referring to Mark

See, for example, Edward Slingerland, What Science Offers the Humanities: Integrating Body

skillful presentations of local points of view ….” For more on Fernandez’s approach to culture,

Johnson’s The Body in Mind: The Bodily Basis of Meaning, Imagination and Reason (Chicago:

albeit with an emphasis on his later work, see Jerry D. Moore, Visions of Culture: An Introduction to

University of Chicago Press, 1987).

Anthropological Theories and Theorists (Walnut Creek: Altamira Press, 1997), chap. 21.

41

32

See, for example, Erwin Panosky, Meaning in the Visual Arts (Garden City: Doubleday, 1955).

James W. Fernandez, “Principles of Opposition and Vitality among the Fang, Journal of Aesthetics

and Art Criticism 25.1 (1966): 53-64; reprinted in Art and Aesthetics in Primitive Societies, ed. Carol F.

42

Jopling, pp. 356-73 (New York: Dutton, 1971). On Fang sculpture and its creators, see also his “The

Institute for the Study of Human Issues, 1980).

Susan M. Vogel, Beauty in the Eyes of the Baule: Aesthetics and Cultural Values (Philadelphia:

Exposition and Imposition of Order: Artistic Expression in Fang Culture,” in The Traditional Artist in

African Societies, pp. 194-220.

43

Fang: An Epic Journey. Written and directed by Susan M. Vogel (Prince Street Pictures Inc. [New

York], 2002).

33

Indeed, the symmetrical character of the figures would seem to Western eyes to give them a

static rather than dynamic character, cf. Frank Willet, African Art (London: Thames and Hudson,

44

1971), p. 220.

based on real events ….” In the booklet accompanying the film, Vogel is careful to qualify this state-

At the beginning of the film, a caption reads: “This is a work of fiction – but everything in it is

ment by adding that “No single object followed this entire path, but many different African objects

34

I am not aware of any other scholar (Western, Fang, or otherwise) discussing this concept.

followed parts of it” (note the adjective African rather than Fang), “The History Behind the Film,” in

Incidentally, Fang visual art and aesthetics seem not to have been examined by scholars of Fang

Idol Becomes Art! Notes and a Roundtable Discussion, ed. Susan M. Vogel (Prince Street Productions

descent.

[New York], 2002), p. 1. The scholarship on which the film is based could be subjected to further

analysis.

35

Cf. Alan Barnard, History and Theory in Anthropology (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,

1999), p. 172.

45

At least, this is what is suggested in Vogel, “The History Behind the Film,” p. 1; it is not all that

clear in the film itself.

36

Fernandez, Bwiti, pp. 390, 578.

46

37

Fernandez, “Principles of Opposition and Vitality,” p. 55 (reprint pp. 360-61).

Julius E. Lips (1895-1950) was Director of the the Rautenstrauch Joest Museum, Cologne’s

ethnographic museum. Having been hounded from his post by the Nazis, he fled to the USA in

1934, where he would teach at various universities. In 1937 he published The Savage Hits Back, Or

38

It is not quite clear whether the second part of this additional analysis can be supported by

the White Man Through Native Eyes (New Haven: Yale Universiy Press), a study of the ways in which

overt Fang views, but the interpretation is consistent with what we know about Fang conceptu-

Europeans had been depicted in sculptures from outside the West. As Lips describes in his chill-

alizations. Fernandez discusses yet another type of balanced opposition in statues, namely

ing Preface to The Savage Hits Back, it was his collection of photos for this book that infuriated the

between references to infants and intimations of old age, an opposition that is said to be explicitly

Nazis, who desperately tried to get their hands on what they considered insults to the “Aryan race.”

Lips returned to (East) Germany in 1948 to teach at the University of Leipzig.

28 Western Scholarship and Fang Statuary from Equatorial Africa

Western Scholarship and Fang Statuary from Equatorial Africa 29

47

“This is the only event in the film not based on a known case” (Vogel, “The History Behind the

Film,” p. 5).

54

In the roundtable discussion on the film that is reported in Idol Becomes Art!, Alissa LaGamma,

curator of African art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, comments: “One thing that

is lacking here is the complete [life] history [of the statue] – the original Fang context in which it

48

Vogel, “The History Behind the Film,” pp. 5-6.

served. The film does not take into account the original source of inspiration for carving the sculpture, the world of ideas and beliefs that were part of its reason of being.” To which Enid Schildkrout,

49

Blurb text of Fang: An Epic Journey.

curator of anthropology at the American Museum of Natural History, New York, replies: “The film

is not about Africa and doesn’t try to be. …. The problem is for people who are concerned with

50

The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, ed. Arjun Appadurai (Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 1986). Most influential have been Appadurai’s “Introduction:

Africa … because they care about that. .… the life history of the piece in the Western art world … is

what the film is actually about” (p. 10).

Commodities and the Politics of Value” and Igor Kopytoff’s contribution “The Cultural Biography of

Things: Commoditization as Process.”

55

Indulging my old love, “the anthropology of aesthetics,” I searched the worldwide web for

Ethnologie+Ästhetik in early 2009 and found a reference to an 1891 essay written by Ernst Grosse,

51

See, for example, The Scramble for Art in Central Africa, ed. Enid Schildkrout and Curtis A.

titled “Ethnologie und Aesthetik” (Vierteljahrsschrift für wissenschaftliche Philosophie 15.4: 392-417).

Keim (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998); Collecting Colonialism: Material Cultural

Researching this programmatic essay and its intellectual context led me to consider the global

and Colonial Change, ed. Chris Gosden and Chantal Knowles (Oxford: Berg, 2001); Hunting the

examination of art in the work of several late-nineteenth-century scholars. See also Wilfried van

Gatherers: Ethnographic Collectors, Agents, and Agency in Melanesia, 1870s-1930s, ed. Michael

Damme, “Ernst Grosse and the ‘Ethnological Method’ in Art Theory,” Philosophy and Literature

O’Hanlon and Robert L. Welsch (Oxford: Berghan Books, 2001); Treasure Hunting? Collectors and

34.2 (2010): 302-312.

Collections of Indonesian Artefacts, ed. Reimar Schefold and Han F. Vermeulen (Leiden: CNWS

Publications, 2002); Colonial Collections Revisited, ed. Pieter ter Keurs (Leiden: CNWS Publications,

2007). An early study is Douglas Cole, Captured Heritage: The Scramble for Northwest Coast Artifacts

(Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1985; reprint 1995). See also, for example, Colonialism and

the Object: Empire, Material Culture and the Museum, ed. Tim Barringer and Tom Flynn (London:

Routledge, 1998), Sensible Objects: Colonialism, Museums and Material Culture, ed. Elisabeth

Edwards, Chris Gosden, and Ruth Phillips (Oxford: Berg, 2001).

52

On trade, collectors, the international art market, and the notion of authenticity, see, for exam-

ple, Christopher B. Steiner, African Art in Transit (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994);

Unpacking Culture: Art and Commodity in Colonial and Postcolonial Worlds, ed. Ruth B. Phillips and

Christopher B. Steiner (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999); Raymond Corbey, Tribal Art

Traffic: A Chronicle of Taste, Trade and Desire in Colonial and Post-Colonial Times (Amsterdam: KIT

Publishers, 2000).

53

See, for example, Exploring World Art, Christraud M. Geary and Stephanie Xatart, Material

Journeys: Collecting African and Oceanic Art, 1945-2000 (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 2007),

Girshick, “Envisioning Art Worlds.” Also, for example, the Fifteenth Triennial Symposium of African

Art, UCLA, May 2011, has as its theme “Africa and Its Diasporas in the Market Place: Cultural

Resources and the Global Economy.”

30 Western Scholarship and Fang Statuary from Equatorial Africa

Western Scholarship and Fang Statuary from Equatorial Africa 31