More Chinese Women Engaged in Physics Women graduate

More Chinese Women Engaged in Physics

Women graduate students in china’s top research institution for physics suddenly boost up to over 30 percent. Will this improve the presentation of women in physics in

China?

Physics is traditionally an arena for men; this is particularly true for a country as China having a history of Feudalism over thousands of years. Unlike elsewhere in the world that the well-established women scientists generally are honored with the appellation ‘Madame’, in

China they are rather preferably labeled with ‘Xiansheng’, a Chinese word that once referred to teacher of both genders, but nowadays is simply the equivalent of Mister in English. The implication is quite clearly: A woman scientist who is successful in career might have manifested certain masculine characters ― in dressing herself and/or in addressing her colleagues.

The under-representation of women in physics is a long-lasting problem that worries

Chinese academic circles. In the CAS Institute of Physics at Beijing, the top institution for physics research in the country, only 6 out of its 108 senior researchers are women, roughly at the same level as in the major scientific powers such as Germany and Japan. But at the topmost levels, the situation is perhaps more acute: Up to now, less than ten women physicists in China have ever been baptized as ‘Xiansheng’.

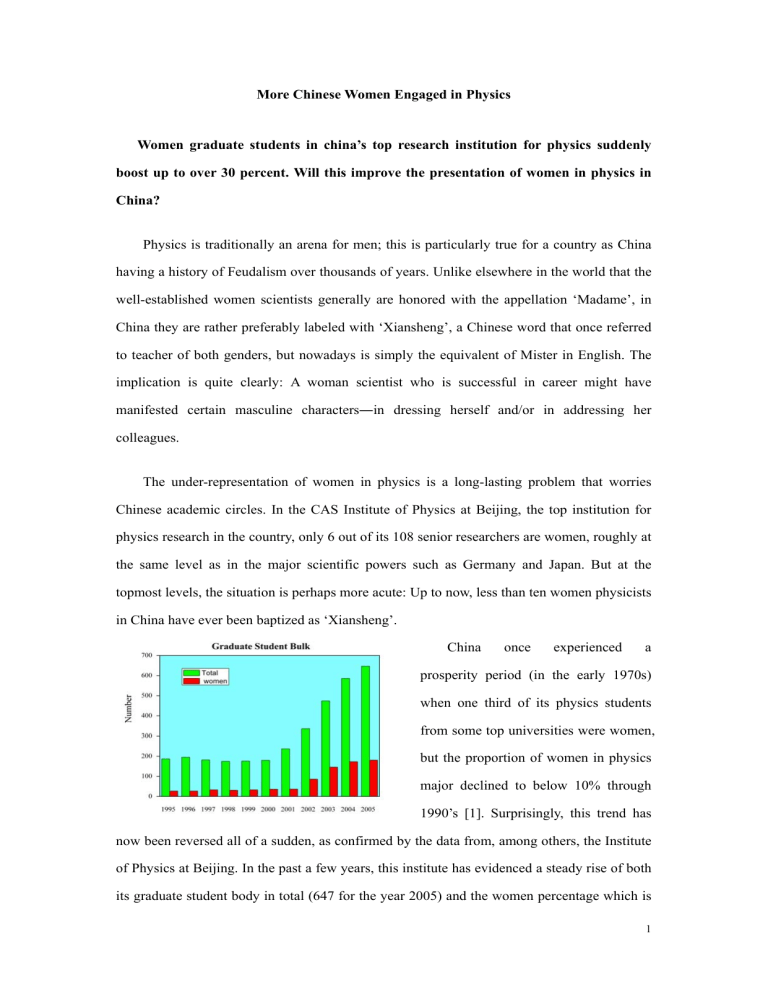

China once experienced a prosperity period (in the early 1970s) when one third of its physics students from some top universities were women, but the proportion of women in physics major declined to below 10% through

1990’s [1]. Surprisingly, this trend has now been reversed all of a sudden, as confirmed by the data from, among others, the Institute of Physics at Beijing. In the past a few years, this institute has evidenced a steady rise of both its graduate student body in total (647 for the year 2005) and the women percentage which is

1

now stabilized at ~30 per cent. At the same period, girl students of the CAS graduate school also make up over 25 percent of its student volume.

The pouring of girls into physics this time is no more driven by “the desire to assert their equality in China’s new society by breaking into fields traditionally closed to them” as before

1970s [1]. Today, Chinese women have equal rights and opportunities in every field as their male counterparts; we can assert with confidence that these girl graduates choose physics at their own will. Admittedly, many of them even cherish the dream to take up physics to a height as the late Madame Chien-Shiung Wu, a native Chinese lady who paved the way to

Nobel prize for C.N. Yang and T. D. Lee with an elegant experiment confirming the parity nonconservation. In the seminars and conferences held at this institute, the audience is often dominated by girls showing a more zealous countenance than their male comrades. Will this then improve the representation of women in physics in China tomorrow? A positive answer to this query at now seems still too optimistic.

Women physics majors suffer a continuing straggle from the main group at later stages of career. Often the gender discrimination is blamed for the consequent women under-representation in physics, but the actual rationale may be much complicated ― there are many other distressing

China’s Madame Wu of tomorrow.

At the institute of physics at Beijing, often girls are in a majority of seminar audience. snags on the career path of women physicists [2].

“I don’t think there is any discrimination against us women”, cited Professor Jin Kuijuan, one of the few women senior-researchers of the Institute of Physics at Beijing, “under-representation of women in physics is rather a problem of physics itself, and lies in the distinctions between men and women. Physics becomes a highly competitive field today. For everybody, man or woman, an interruption in career for a while may imply retreating from the research frontier forever. But the early- and mid-career periods

(roughly up to 35 years old) overlap the golden times for a woman who has to finish the transition from a young girl to a responsible, caring mother. How can we expect girls in love

2

and young women in pregnancy or holding a small baby in arms to equally concentrate on physics as their male colleagues do? Even after giving birth, a woman has to devote more time to the family, which unavoidably disadvantages her competition for senior position.

Many promising women are then steered out of physics.”

Women participation profits science in various aspects: They not only provide more intuitions into the problems with their precious brains of other nature and contribute to laboratory works that require extraordinary dexterity and patience, but simply a healthy working environment of mixed genders is also beneficial. In order to sustain a reasonable women percentage in science, Jin continued, “The wise choice is to face the particular problems that impede the career path of women.” Some balance mechanisms have to be introduced so as to encourage the girl graduates to take up physics as their life’s work. The

Chinese government, granting agencies, research institutions and universities should immediately take some applicable measures, concerning from fund distribution to child-care service, to boost the career of women physicists.

It is rejoicing that some practical measures are under consideration now in China for the promotion of women physicists. Accordingly, the National Natural Science Foundation of

China promises more funds and special programs for women researchers, especially the beginners. Moreover, the lady-first-principle in recruiting staffs into the fields that suffer crucial gender imbalance also becomes a topic of serious discussion in the research institutions and universities. These are clearly good news for both the women physicists and the physics itself in China. Will we see a blooming of China’s physics with the participation of more women, as its performance in the Olympiad in the last two decades? Let’s wait and see.

( Professor Cao Zexian is at the Institute of Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences,

Beijing 100080, China.

)

References

[1] Science 295, 263 (2002).

[2] Nature 437, 296 (2005).

3