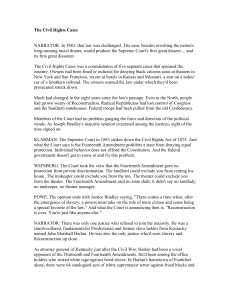

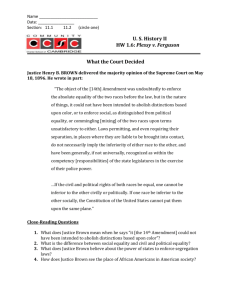

Reassessing the Disincorporation of the Bill of Rights

advertisement