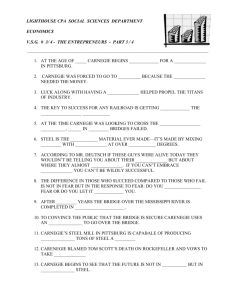

1 The 1892 Homestead Strike: A Story of Social Conflict in Industrial

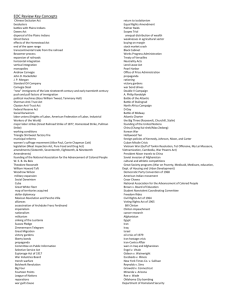

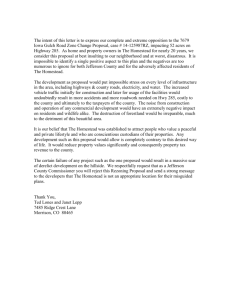

advertisement