Natural Gas in South Asia Pakistan and Bangladesh: current issues

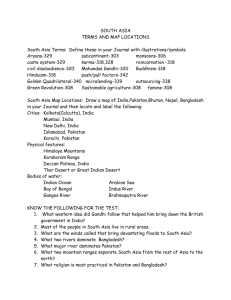

advertisement