Software engineering education (SEEd): is

advertisement

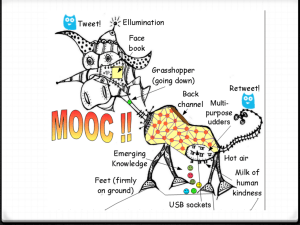

ACM SIGSOFT Software Engineering Notes Page 14 Software Engineering Education (SEEd) Mark A. Ardis School of Systems and Enterprises Stevens Institute of Technology Hoboken, NJ 07030 USA mark.ardis@stevens.edu Peter B. Henderson, Emeritus Department of Computer Science & Software Engineering Butler University Indianapolis, Indiana 46208 USA phenders@butler.edu DOI: 10.1145/2347696.2347720 http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/2347696.2347720 Is Software Engineering Ready for MOOCs? The latest rage in university education is Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs). These courses attract thousands of students for each offering. Students view lectures online and submit their quizzes and homework to automated grading systems. How well does this format fit software engineering? This column looks at some of the choices made by Armando Fox and David Patterson at the University of California, Berkeley in the creation of their course: Software Engineering for Software as a Service (SaaS). Some of those choices reveal advantages and disadvantages of adopting the MOOC approach. Fox and Patterson teach a longer version of their course on campus at Berkeley, CS 169: Software Engineering. The lectures from the first five weeks of the campus course were recorded for use in the online version. Although the online course covers only about a third of the material in the campus course, it provides a surprising amount of useful introductory material, and it gives students a chance to experience many of the key tasks and activities of software engineering. One of the choices made by Fox and Patterson in designing their campus course was to give students a quick introduction to their chosen software development process and tools at the start of the course. This enables students to start practicing software development after only a few hours of instruction. For example, in the second homework assignment students modify a web application and see how their changes result in new functionality for the user of the app. They use standard tools and methods just like real software developers. To be fair, students who take the campus course have already completed prerequisite programming courses. Online students without any programming background would probably find the September 2012 Volume 37 Number 5 homework assignments quite difficult. But students are able to accomplish quite a bit by writing a relatively small amount of code. This is the result of another choice of Fox and Patterson: selecting Ruby and Rails for the development environment. Ruby and Rails provide most of the infrastructure needed for creation of web applications and services. They also come with additional tools that enable effective software development practices. Students in the SaaS course practice behavior-driven development with Cucumber and RSpec. By describing tests in terms that are easily understood by customers, students learn to appreciate some of the difficulties that stakeholders have in describing their goals and intentions. They also learn to appreciate the value of testing early and often. Fox and Patterson made a good case for their approach in a recent CACM article [1]. Their survey of Berkeley alumni convinced them that they should include several modern software development techniques, including: version control, working in a team, software-as-a-service, design patterns, unit testing skills, Ruby on Rails, cloud computing, test-first development, user stories, low-fidelity user interface mockups, and measurement of progress in terms of velocity. All of these topics and techniques are included in their campus course, and many of them are also in the online version. Most of these techniques translate well to MOOCs, especially those involving individual programming tasks. Programming assignments can be assessed using automated systems fairly easily. Teamwork, however, is an unknown. There is nothing in principle that prevents students from working effectively in geographically distributed teams, but to my knowledge no one has tried it in the MOOC format yet. Not all software engineering is about software-as-a-service. Some software systems are created as embedded systems, some are shrink-wrapped products, some are the "glue" that hold other components together, to name just a few alternatives. And not all skills needed by software engineering are exercised by developing web applications. Requirements elicitation, review techniques, and effective presentation skills are also important. It is these more social skills that may be the most difficult to practice and assess in the MOOC format. Again, there is nothing in principle that prevents students from participating in any of these activities at a distance, but lack of co-location certainly make them more difficult. Also, it is hard to see how robotic grading can be applied to these exercises. Programs can be tested to see if they produce the correct results, but elicitation activities and reviews have no oracle. Perhaps this is an active research project somewhere. An interesting development in MOOCs that might help develop the more social side of software engineering is the spontaneous creation of study groups and self-appointed teaching assistants. Both of these have been very effective in the MOOC by Fox and Patterson. We look forward to seeing how other software engineering courses adapt to the MOOC format. References 1. Armando Fox and David Patterson, Crossing the Software Education Chasm: An Agile approach that exploits cloud computing, CACM 5(5), 44-49, May 2012.