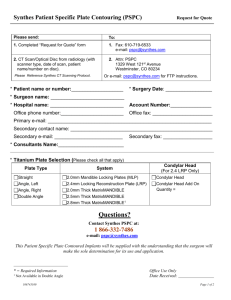

Synthes

advertisement