A GUIDE TO NEW YORK STATE TAXES:

History, Issues and Concerns

Marilyn M. Rubin

February 2011

A GUIDE TO NEW YORK STATE TAXES:

HISTORY, ISSUES AND CONCERNS

Marilyn Marks Rubin

John Jay College

February 2011

Funded by the Peter J. Solomon Family Foundation

Marilyn Marks Rubin

Professor

John Jay College

City University of New York

445 W. 59th Street

New York City, NY 10019

(212) 237-8091

mrubin@jjay.cuny.edu

Peter J. Solomon

Chairman

Peter J. Solomon Company

520 Madison Avenue

New York City, NY 10022

(212) 508-1600

pjsolomon@pjsolomon.com

http://www.pjsolomon.com

Preface

The Guide to New York State Taxes is a companion to the Guide to New York City Taxes published in

December 2010. The origin of the City Guide is a report on NYC taxes prepared for me by Dr.

Marilyn Rubin, a consultant to my office when I was Deputy Mayor for Economic Policy and

Development under Mayor Edward I. Koch.

In the late 1970s, New York City and State were in the midst of a fiscal crisis – much like today.

Decisions on taxes were then and are now essential to the vitality of the State and City, yet those making

policies and opining on them often do not have sufficient knowledge. We hope that this Guide, clearly

defining the history of NYS taxes, their rates and bases, who pays them and the issues associated with

each will allow more informed tax policy decisions and a better understanding of the effect of changes.

Dr. Rubin prepared the 2011 NYS Guide and its companion NYC Guide with a grant from the Peter J.

Solomon Family Foundation under the auspices of John Jay College where she is a Professor of Public

Administration and Economics and Director of the MPA Program. Dr. Rubin is an expert on state and

local taxes and is an elected fellow of the National Academy of Public Administration (NAPA), chartered

by the U.S. Congress to help government leaders build accountable, efficient and transparent

organizations. I am indebted to Dr. Rubin for her thorough and thoughtful analysis. Her colleague, Dr.

Catherine Collins at George Washington Institute of Public Policy, provided extensive input into the

report. Adjunct faculty members at John Jay College, Caroline McMahon and Michael Walker, assisted in

data collection and in the preparation of the Guide as did Annemarie Eimicke and Dov Horwitz, former

students in the College’s MPA Program.

Dr. Rubin and I are grateful to the many professionals who have read and commented on the State Guide

including several experts in NYS agencies dealing with State taxes. We thank Stephen Solomon and

Kenneth Moore of Hutton & Solomon, LLP, for their input on some of the more technical aspects of the

State’s taxes and the many associations and companies that have provided comments on sections of the

Guide and data used in its exhibits.

In closing, the work is ours and, while we have received many helpful suggestions from the persons listed

above, we bear full responsibility for its accuracy and completeness. We welcome comments.

Peter J. Solomon

Chairman, Peter J. Solomon Company, L.P.

February 2011

CONTENTS

Executive Summary ………………………………………………………………………

i

Personal Income Tax ……………………………………………………………………..

1-1

Sales/Use Tax …………………………………………………………………………….

2-1

Cigarette/Tobacco Products Tax ………………………………………………………..

3-1

Alcoholic Beverage Tax ………………………………………………………………….

4-1

Motor Fuel Tax …………………………………………………………………………..

5-1

Highway Use Tax…………………………………………………………………………

6-1

Auto Rental Tax ………………………………………………………………………….

7-1

Corporation Franchise Tax ………………………...……………………………………

8-1

Corporation and Utility Tax …………………………………………………………….

9-1

Insurance Tax …………………………………………………………………………….

10-1

Bank Franchise Tax …………………..………………………………………………….

11-1

Petroleum Business Tax ………………………………………………………………….

12-1

Real Estate Transfer Tax ………………………………………………………………...

13-1

Estate Tax …………………………………………………………………………………

14-1

Executive Summary

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Introduction

The purpose of the Guide to New York State

Taxes is to provide information on State taxes to

a wide range of readers in a format that is broad

in scope and non-technical in presentation.

The State has several websites that present

information on NYS taxes including the annual

Handbook on New York State and Local Taxes

and the Economic and Revenue Outlook that

accompanies the annual Executive Budget. Both

describe the NYS tax structure, but neither

provides a broad non-technical picture of State

taxes, showing their structural elements as well

as other relevant details – how they have

evolved over time, how much revenue they

generate, how they compare to similar taxes

imposed in other states and whether local

governments impose a similar tax.

NYS levies 14 major taxes including the

Personal Income Tax, the Sales/Use Tax, five

business taxes, five excise taxes, and two

transfer taxes. Exhibit 1 at the end of this section

shows the revenues from each tax.

Personal Income Tax. The Personal Income

Tax (PIT) is the primary NYS tax source,

accounting for 60.1% of State tax revenues and

27.4% of total State revenues in FY2010 (see

Figure 2). The tax is imposed on NYS residents

and on non-residents with income attributable to

NYS sources. Non-residents generate more than

15% of State PIT revenues.2

The Guide presents this information for the

State’s major taxes as of Fiscal Year 2010.1 It

also discusses issues and concerns that must be

addressed if NYS is to maintain its competitive

position as a place to conduct business and its

reputation as a desirable place to live.

Taxes and Other NYS Revenue Sources

Taxes are the main source of NYS revenues. In

FY2010, of the $126.9 billion in total State

revenues, 45.5% was attributable to taxes (see

Figure 1).

Sole proprietors, partnership members and S

Corporation owners/shareholders are subject to

the PIT rather than to a NYS business tax. For

sole proprietors, the PIT is imposed on business

net earnings. For partnership members, the tax is

imposed on their distributive share of partnership income. Limited Liability Companies

(LLCs) are taxed as partnerships under NYS Tax

Law unless they choose to be treated as

corporations. For S Corporations, income passed

through to individual owners/shareholders is

subject to the PIT.

Mobility Tax. Effective 2009, NYS imposed the

Metropolitan Commuter Transportation Mobility

Tax, a payroll tax on most employers3 and selfemployed individuals conducting business in

i NYC and the other 7 counties in the MCTD:

Dutchess, Nassau, Orange, Putnam, Rockland,

Suffolk and Westchester. NYS distributes all

proceeds from the Mobility Tax to the MTA.

Personal Income taxes, such as the State

PIT, are always paid by individuals. Payroll

taxes may either be withheld from employee

wages or paid from the employer's own

funds. For the Mobility Tax, employers are

prohibited by law from deducting any

portion of the tax from employee wages or

compensation.

The Mobility Tax rate is 0.34%. For individuals,

the tax is imposed on net earnings from selfemployment allocated to the MCTD.4 Partners –

including members of LLCs treated as

partnerships for purposes of the Federal Income

Tax – are subject to the tax on net earnings

allocated to the MCTD. Corporations, including

S Corporations, pay the tax on the payroll of

workers employed in the MCTD. Distributions

to S Corporation owners/shareholders are not

subject to the Mobility Tax.

Sales/Use Tax. The second largest source of

NYS tax revenues is the Sales/Use Tax. It

generated $10.5 billion in FY2010, accounting

for 18.2% of NYS tax revenues and 8.3% of

total State revenues. The Sales Tax is imposed

on the sale of most goods purchased in NYS and

on enumerated services provided in the State.

The Compensating Use Tax is imposed on

purchases made outside of the State and brought

into it for use.

0.34% Mobility Tax on the payroll of workers

employed in the MCTD.5

Excise Taxes. NYS levies excise taxes on

selective commodities or transactions – cigarettes, alcoholic beverages, motor fuels,

highway use, and auto rentals. In FY2010, the

State’s five excise taxes generated $2.3 billion in

revenues, accounting for 4.0% of NYS taxes and

1.8% of total revenues.

Transfer Taxes. The two other major taxes

imposed by the State are the Real Estate

Transfer Tax (RETT) and the Estate Tax. In

FY2010, the RETT generated $493 million,

accounting for 0.9% of tax revenues and 0.4% of

total State revenues. The Estate Tax produced

$866 million, accounting for 1.5% of tax

revenues and 0.7% of total State revenues.

Trends in NYS Tax Revenues

NYS collected close to $58 billion from all taxes

in FY2010, an increase of 37% over FY2000.

These revenues are, however, in current or

nominal dollars that do not take inflation into

account. Constant dollar revenues are adjusted

for inflation and show real tax changes over

time. FY2010 constant dollar revenues were 7%

above those in FY2000 but 9% below the peak

reached in 2008 (see Figure 3).

Business Taxes. The third largest source of

NYS tax revenues comes from business taxes

imposed on general corporations, banking

corporations, insurance companies, utilities and

petroleum companies. In FY2010, the five taxes

generated $7.5 billion, accounting for 12.9% of

NYS taxes and 5.9% of total State revenues.

Business tax revenues include receipts from the

temporary 17% surcharge imposed in 1982 on

corporate taxpayers conducting business in the

MCTD. As discussed above, corporations doing

business in the MCTD are also subject to the

Because of the predominance in the NYS tax

base of the PIT and other economically sensitive

taxes, constant dollar tax revenues closely track

economic conditions in the State6 (see Figure 4).

ii Local Government Taxes

State taxes must be considered in conjunction

with local government taxes to determine the

total tax burden in NYS. More than half of total

taxes paid in NYS are collected by local

governments.7

The Real Property Tax (RPT) is the primary

source of local government revenues. In

FY2009, it accounted for 78% of local

government tax revenues and 41% of total local

government revenues, with the exception of

NYC (see Figure 5). NYC is excluded because

its revenue structure differs significantly from

that of all other jurisdictions in the State.

In addition to the Real Property Tax, NYC is the

one local government in NYS authorized to levy

a personal income tax, business income taxes

and several other taxes.8 The City of Yonkers

also levies an individual income tax. Certain

other local governments including cities,

counties, and school districts are authorized to

impose sales/use taxes, taxes on hotels and motels, real estate transfer taxes, mortgage recording taxes and utility taxes.

Real Property Tax. The Real Property Tax

(RPT) is levied in more than 4,700 taxing

jurisdictions in NYS based on the value of

residential and non-residential real properties

with certain exceptions.9 Reliance on the RPT

varies by type of government. In FY2009,

counties received 23% of their revenue from the

RPT, cities 25%, towns/villages 53% and school

districts 53%.10

Included in the school districts’ RPT share are

payments received from the NYS School Tax

Relief (STAR) fund, one of the State’s several

Special Revenue Funds discussed later in this

section. STAR is supported by a portion of NYS

Personal Income Tax receipts. Excluding STAR

payments, the RPT accounted for 46% of school

district revenues in FY2009.

The State and the RPT. Although NYS does

not levy a State real property tax, it has a major

role in determining the structure and administration of local property taxes. Some of the

State’s regulations allow local governments

discretion in their adoption. Other regulations

are mandatory, either constitutionally or

statutorily.

The expansive role of the State in local property

taxation and in all other taxes is explained by

what is known as Dillon’s Rule. Established in

1872 in a treatise on municipal corporations

authored by Iowa Supreme Court Judge John F.

Dillon, the Rule dictates that municipalities are

limited to powers explicitly given to them by the

state. The creature of the state principle remains

the legal doctrine governing current state-city

relationships throughout the U.S., as modified

by individual state laws permitting home rule.

Most states, including New York, have modified

Dillon’s Rule by providing home-rule powers to

certain or all local governments, either under

their constitutions or by statute. Home-rule

iii municipalities are taken out from under Dillon’s

Rule and permitted to operate under their own

charter which establishes local governance and

administrative practices. In general, however,

home-rule authority does not extend to

autonomy over the power to tax.

Other than setting annual Real Property Tax

rates – and even this action is taken within NYS

constitutional and statutory constraints – local

government actions related to the RPT and to

other taxes are subject to initiation or approval

by the Governor and State Legislature with the

exception of the assessing function. The State

provides guidance for assessment but cannot tell

local assessors what an assessment should be.

Only the courts or a locally appointed appeals

body may do so.

Dedicated Tax Revenues

Unlike most private sector entities that keep a single

set of accounts for all transactions, governments

generally divide their financial resources into

separate accounting entities called funds. Receipts

that flow into these funds are derived from several

sources including state taxes.

General Fund. The majority of NYS tax

revenues are deposited in the State’s General

Fund, the primary operating fund of the State.

The revenues in the General Fund are available

to pay for most purposes that the State is legally

empowered to pursue.

Budgetary shortfalls always refer to the gap

between revenues and expenditures in the

General Fund.

Other Funds. NYS revenues also flow into

other funds which are available for certain

operations but have statutory restrictions on their

use.11

Special Revenue Funds. Special revenue funds

are earmarked for specific purposes and are

supported by dedicated taxes and other revenue

sources. An example of a special revenue fund is

the NYS School Tax Relief Fund (STAR).

STAR provides Property Tax relief for State

residents with incomes below a certain level

by exempting a portion of the taxable value

of their primary residence from local school

district property taxes.

NYC residents – both owners and renters –

with annual incomes below a certain level

are also eligible for a refundable STAR

credit against City PIT liability.

STAR is financed by a dedicated portion of

NYS Personal Income Tax collections that

are used (1) to reimburse school districts for

forgone Property Taxes resulting from

STAR reductions to the taxable value of

taxpayer properties; and (2) to reimburse

NYC for forgone revenues resulting from

the STAR credit taken by taxpayers against

their City PIT liability.

Debt Service Funds. Debt service funds are

established to cover interest and repayment of

principal on the State’s general obligation debt,

special obligation debt, lease purchases, and

contractual obligations. An example of a debt

service fund is the Local Government Assistance

Tax Fund (LGATF).

To eliminate annual cash flow borrowing in

the first quarter of each fiscal year, 1990

legislation authorized the Local Government

Assistance Corporation (LGAC) to issue

bonds to finance payments to local

governments previously funded by the State.

By 1995, the Corporation had issued its

entire authorization. LGATF revenues are

dedicated to the payment of debt service on

outstanding LGAC bonds.12

LGATF is financed by a dedicated portion

of NYS Sales/Use Tax receipts. All revenue

in excess of the aggregate amount required

for debt service payments must be deposited

in the General Fund.

Capital Projects Funds. Capital projects funds

finance the acquisition and construction of State

facilities and projects and provide financial

assistance to local governments and public

authorities. An example of a capital projects

fund is the Dedicated Highway and Bridge Trust

Fund (DHBTF).

The Dedicated Highway and Bridge Trust

Fund supports transportation projects such

as the reconstruction and preservation of

iv

NYS and local roads. The Fund is also used

to pay debt service on State-supported

Dedicated Highway and Bridge Trust Fund

Bonds.

The DHBTF is financed by dedicated

receipts from the Motor Fuel Tax, Highway

Use Tax, Auto Rental Tax, Petroleum

Business Tax, a portion of the Corporation

and Utility Tax, and by motor vehicle fees.

Exhibit 2 provides information concerning the

NYS taxes dedicated to the Special Revenue,

Debt Service, and Capital Projects Funds.

Although fund revenues are meant to be used

solely for purposes described in their authorizing

legislation, special language may allow for

transfer of funds, particularly to the General

Fund.

Tax Expenditures

Tax expenditures can be defined as government

spending through the tax system. They result in

revenue losses to government attributable to tax

law provisions that permit taxpayers to reduce

their taxes by subtracting exclusions,

exemptions and deductions from their gross

income, applying tax credits against their tax

liability, taking tax deferrals and using

preferential tax rates.

Exclusions, exemptions and deductions

reduce taxable income. For example, Bank

Taxpayers are allowed a net operating loss

deduction (NOLD) – subject to certain

restrictions – that reduces their taxable

income.

Credits are subtracted dollar-for-dollar from

tax liability thus reducing tax payments. For

example, taxpayers are permitted to take a

credit for college tuition paid against their

PIT liability. Certain credits are refundable

which means that if the value of the credit

exceeds tax liability, the excess is refunded

to the taxpayer.

Tax deferrals result from delayed

recognition of income. For example, money

placed into certain retirement accounts is not

taxed until withdrawn.

Preferential tax rates apply lower tax rates to

part or all of a taxpayer's income. For

example, some small businesses and certain

manufacturing and emerging technology

companies pay a 9A Corporation Franchise

Tax rate of 6.5% on their net income rather

than the 7.1% paid by most other

corporations.

Estimated forgone revenues to NYS resulting

from each of its tax expenditures ranges from

under a million dollars to more than a billion

dollars per year.13 Tax expenditures with an

estimated revenue impact of more than a billion

dollars in FY2010 include:

The exclusion of interest, dividends and

capital gains from Subsidiary Capital on the

9A Corporation Franchise Tax

The interest deduction on the Personal

Income Tax

The exemption of certain foods from the

Sales/Use Tax.

Comparisons with Other States

States differ with respect to the taxes they

impose, their tax structure and rates, and the

authority given to local governments to levy

their own taxes. Differences among states are

significant and contribute to their competitive

position for businesses and residents.

Several measures are used to compare taxes

among the states; individual state rankings

depend on which measure is applied. Table 1

shows how NYS ranks relative to four

neighboring states applying the two most

commonly used measures: (1) Per Capita State

Taxes and (2) State Taxes as a Percent of

Personal Income. Both measures are based on

data collected and published by the U.S. Bureau

of the Census.

Per capita state taxes measures tax

collections relative to the size of the

population served by government.

State taxes as a percent of personal income

relates tax payments to an indicator of state

economic performance.

As seen in Table 1, NYS ranks higher, i.e., has a

greater tax burden, than its four neighboring

states with one exception. Among all 50 states,

New York ranks 7th and 15th, indicating that

several states have greater tax burdens based on

the two measures.

v Table 1:NYS and Four Neighboring States: State Tax

Burden Rankings, 2009*

Measure

NY

NJ

PA

CT

MA

Per Capita

7

10

22

5

11

State Taxes

State Taxes as

15

28

29

19

31

% of Personal

Income

*Possible values range from 1 to 50. The lower the

ranking, the higher the tax burden.

Source: Federation of Tax Administrators based on U.S.

Census State and Local Government Finances

When local taxes are added, Table 2 shows that

NYS does not fare as well. According to the Tax

Foundation, a Washington D.C. research

organization, NYS has a heavier state/local tax

burden than all states with the exception of New

Jersey, and a less competitive business tax

climate than all other 49 states.14

Table 2: NYS and Four Neighboring States:

State/Local Tax Burden Rankings

Measure

NY

NJ PA

CT

MA

State/Local

2

1

11

3

23

Tax Burden

2008*

Business Tax

50

48

26

47

32

Climate

2011**

*Possible values range from 1 to 50. The lower the

ranking, the greater the tax burden.

**A larger number indicates a more unfavorable business

tax climate with 50 the lowest possible ranking.

Source: The Tax Foundation

Common Issues and Concerns

The Guide to New York State Taxes describes

the structural elements of each major NYS tax as

well as other relevant details about the tax – how

it has evolved over time, how much revenue it

generates, and how it compares to similar taxes

in other states.

Although the taxes differ, several issues and

concerns are common among them. They are

discussed briefly below and explained more

fully in the descriptions of the individual taxes

in the Guide. Exhibit 3 shows which of the

State’s major taxes are affected by the common

issue and concern.

High Taxes. As discussed above, NYS has the

least favorable business tax climate of all 50

states and the highest state/local tax burden of

all states with the exception of New Jersey. The

many taxes levied by NYC and other local

governments on top of those imposed by NYS

are a major factor contributing to the State’s

unfavorable tax burden rankings.

Combined NYS/NYC Taxes. NYS levies many

taxes on the same base as NYC. Of the 19 taxes

imposed by the City, 11 are also levied by

NYS.15 Comparative tax burden studies always

show NYC with the highest or close to the

highest combined city/state burden in the nation.

The City has the highest combined

state/local personal income tax rate and the

highest combined state/local corporate

income tax rate in the U.S.

The combined NYS/NYC Real Property

Transfer Taxes and Mortgage Recording

Taxes give NYC the highest real estate

closing costs in the U.S.

Taxes on Utilities. Variation among the states in

electricity, telecommunications and other utility

costs is primarily attributable to state and local

taxes. In NYS, taxes imposed on utilities include

the State Gross Receipts and 9A Corporation

Franchise Taxes, local business income/gross

receipts taxes, State/local sales taxes and local

property taxes. Surcharges also contribute to

high utility costs in NYS.

NYS and local government taxes/fees paid

by utilities are passed along to customers in

their bills, with few exceptions. For

example, for an average residential customer

living in NYC, taxes/fees represent almost

half of their electricity delivery bill.

NYS ranks second to Hawaii in the price of

electricity paid by most consumers; it ranks

fourth highest among all states in taxes

imposed on mobile telecommunications

providers.

Property Taxes. Residential property taxes in

many NYS jurisdictions are among the highest

in the nation. In 2009, of 10 counties in the U.S.

with the highest ratio of median real estate taxes

to median home values, 9 were located in NYS:

Monroe, Niagara, Wayne, Chemung, Chauvi tauqua, Erie, Onondaga, Steuben and Madison.

Property Taxes as a percent of median home

values in these counties ranged from 2.43% to

2.89%; the U.S. average was 1.04%.16

Electronic Commerce. The growth in ecommerce is a new challenge, with rapidly

changing communications technologies making

geographic borders less relevant for many taxes.

The increase in e-commerce sales and the failure

of most taxpayers to remit taxes on their

purchases has negatively impacted the State’s

Sales/Use Tax collections and those of local

governments that impose similar taxes. The loss

in 2009 of NYS/NYC Sales and Use Tax

revenues resulting from untaxed e-commerce

sales is estimated at $655 million.17 Cigarette

Tax revenues are also adversely affected by

Internet sales.

The growing use and reliability of

telecommunications technology also means that

more business can be conducted electronically

with physical location no longer a necessity.

This, too, has an adverse impact on NYS and

NYC tax revenues as businesses act to reduce

their tax liabilities through increased use of the

Internet and emerging technologies.

Government Regulatory Reforms. Passage of

the Federal Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA)

in 1999 removed the regulatory demarcation

between banks, securities firms, and other

financial institutions including insurance

companies. Currently, banks are taxed under

the NYS Bank Tax; other financial services

institutions under the 9A Corporation Franchise

Tax. NYS is considering a single tax structure

for financial institutions. A proposal prepared

by the State has been forwarded to members of

the industry for review and comment. The

recently enacted Federal Dodd-Frank Wall

Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act has

changed the regulatory environment for

financial institutions, reinforcing the importance

of restructuring the State’s taxation of banks

and other financial institutions.

The Insurance Industry. GLBA confirmed the

intent of Congress that insurance companies

continue to be regulated by the 50 states. The

Dodd–Frank law, however, is giving the Federal

government an increasing role in the industry. It

provides for the creation of the first office in the

Federal government focused on insurance. One

of the functions of the office is to monitor the

insurance industry for systematic risk purposes.

Utilities. Many issues pertaining to utility

taxation relate to deregulation, particularly of

companies supplying electricity, natural gas and

telecommunications services. Deregulation has

changed the marketplace so that regulated

utility companies now compete with other

companies in providing electricity, natural gas

and telephone services.

Deregulation makes the distinction between the

taxation of NYS’s 9A Corporation Franchise

Taxpayers and Utility Taxpayers difficult to

rationalize. Most NYS corporations pay taxes

based on net income. Regulated utilites

companies are taxed on net income and gross

receipts.

Transparency. One of the standards of a good

tax and a good tax system is that they be

transparent to taxpayers. The meaning of the

different tax law provisions ought to be

straightforward and the mechanics of calculating

the tax should not be a mystery. The complexity

of several NYS taxes makes them opaque. The

94-page instruction booklet issued to taxpayers

with PIT tax forms illustrates the complexity of

the State’s major source of tax revenues. The

booklet contains instructions for three tax forms,

several tables explaining how to calculate tax

liability and advice to taxpayers for claiming

credits and deductions.

Tax Expenditures. The multi-billion dollar

revenue impact on NYS of tax expenditures

includes refunds to taxpayers by the State for

refundable credits.

For refundable credits, if the value of the

credit exceeds tax liability, the excess is

refunded to the taxpayer. For example, in

2006, the State refunded $208 million to 9A

Corporation Franchise Taxpayers of which

$41million was for Brownfield Credits.18

Some of these credits were for remediation

of Brownfield sites; some for redevelopment

vii

of the remediated sites. Brownfield credits

taken against the PIT are also refundable.

Non-refundable credits are credits that allow

the taxpayer to reduce tax liability to zero.

The taxpayer is permitted to carry forward

many unused non-refundable credits to

reduce taxes in future years. For example,

in 2006, the unused carry forward

component of the Investment Tax Credit

(ITC) taken against the 9A Corporation

Franchise Tax was $1.3 billion.19

The annual tax expenditure report issued by the

State provides information concerning NYS

credits and other tax expenditures. No evaluation

of the effectiveness of refundable credits or any

other tax expenditures is included in the report.

Conclusions

NYS imposes a wide variety of taxes on its

residents, businesses and visitors. Most of the

State’s taxes were enacted more than 50 years

ago, long before dramatic technological

advances, new economic structures and

deregulation changed the environment in which

taxes are imposed. The information presented in

the Guide can provide a baseline for efforts

undertaken to improve and modernize the

State’s tax structure.

Endnotes

1

The NYS Fiscal Year runs from April 1 to March

31; the NYC Fiscal Year from July 1 to June 30.

2

NYS Division of the Budget. 2007 is the latest year

for which these data are available.

3

The only employers exempt from the tax are

agencies/instrumentalities of the U.S., the United

Nations, or an interstate agency or public corporation

created under an agreement or compact with another

state or Canada. Public school districts have their

mobility tax payments fully reimbursed by NYS in

the fiscal year following payment.

4

The tax does not apply if the individual’s allocated

net earnings from self employment are $10,000 or

less for the tax year.

5

The employer’s payroll expense must be greater than

$2,500 in a calendar quarter before the tax applies.

6

Economic conditions are measured by the NYS Index

of Coincident Economic Indicators developed by the

Federal Reserve Bank of New York. The Index

combines indicators of economic activity, including

employment, to measure overall changes in economic

conditions in NYS.

http://www.ny.frb.org/research/regional_ economy/

coincident_nystate.html.

7

2008 is the latest year for which composite local

government tax data are available from the U.S.

Census of Government Finances, the only published

source for such data.

8

Among the taxes levied by NYC are: the General

Corporation Tax, Bank Tax, Utilities Tax,

Unincorporated Business Tax, Commercial Rent Tax

and the Hotel Tax.

9

NYS law mandates that property owned by

government entities and certain not-for-profit

organizations be fully exempt from the RPT. Other

properties are partially exempt under various

programs.

10

NYS Office of the Comptroller (2009 data for fire

districts are not available). http://www.osc.state.ny.

us/ localgov/datanstat/findata/index_choice.htm.

11

Government funds not included here are Proprietary

Funds and Fiduciary Funds.

12

There has been no NYS intra-year short-term

borrowing since FY1994. Currently, any State intrayear short-term borrowing requires a declaration of

emergency by the Governor and legislative leaders

and must be paid down within four years following

such a declaration.

13

Estimated FY2010 revenue impacts of all NYS tax

expenditures can be found in the 20th NYS Annual

Report on Tax Expenditures

http://www.budget.state.ny.us/pubs/archive/fy0910ar

chive/eBudget0910/fy0910ter/TaxExpenditure0910.pdf.

14

Tax Foundation http://www.taxfoundation.org/news/show/335.html

and

http://www.taxfoundation.org/publications/show/226

61.html.

15

The 19 taxes include the tax on Off-Track Betting

administered by the NYC Off-Track Betting

Corporation (OTB) which was closed as of December

2010.

16

Tax Foundation http://www.taxfoundation.org/

taxdata/show/1888.html

17

Bruce et al. State and Local Government Sales Tax

Revenue Losses from Electronic Commerce.

http://cber.bus.utk.edu/ecomm/ecom0409.pdf .

18

2006 latest data available in NYS Annual Report on

Tax Expenditures. As a result of tax law provisions

enacted in the 2010 NYS budget, participants in the

Brownfield Program with cumulative tax credits in

excess of $2 million must defer them.The deferral

will apply to credits that could otherwise have been

claimed in tax years 2010, 2011 and 2012.

19

Ibid.

viii Exhibit 1: NYS General Fund and All Funds Revenues, FY2010 ($ in Millions)

General Fund

All Funds1

% of

% of

Total

% of Total

Total

% of Total

NYS

NYS

NYS

NYS

Revenues

Taxes

Revenues

Revenues

Taxes

Revenues

Total Revenues

$52,556

$126,748

All Taxes

36,997

100.0

70.4

57,668

100.0

45.5

Personal Income Tax

22,654

61.2

43.1

34,751

60.1

27.4

Sales and Excise Taxes

8,087

21.9

15.4

12,852

22.2

10.1

Sales/Use Tax

7,405

20.0

14.1

10,527

18.2

8.3

Excise Taxes

682

1.8

1.3

2,312

4.0

1.8

Cigarette and Tobacco Products

456

1.2

0.9

1,366

2.4

1.1

Alcoholic Beverage

226

0.6

0.4

226

0.4

0.2

Motor Fuel

507

0.9

0.4

Highway Use

137

0.2

0.1

Auto Rental

76

0.1

0.1

Business Taxes

5,371

14.5

10.2

7,459

12.9

5.9

General Corporation Tax (9A)

2,145

5.8

4.1

2,511

4.3

2.0

Bank Tax

1,173

3.2

2.2

1,399

2.4

1.1

Insurance

1,331

3.6

2.5

1,491

2.6

1.2

Petroleum Business Taxes

1,104

1.9

0.9

Corporation & Utility Taxes

722

2.0

1.4

954

1.7

0.8

Transfer Taxes

866

2.3

1.6

1,359

2.4

1.1

Real Estate Transfer Tax

493

0.9

0.4

Estate and Gift Taxes

866

2.3

1.6

866

1.5

0.7

Other Taxes2

19

*

*

1,247

2.2

1.0

Miscellaneous Receipts

3,888

7.4

23,557

18.6

Federal Grants

71

0.1

45,523

35.9

Transfers

11,600

22.1

1

Includes General Fund, Special Revenue Funds, Debt Service Funds and Capital Projects Funds.

2

Includes the Pari-Mutuel Tax, the Racing Admissions Tax, the Boxing/ Wrestling Exhibitions Tax. Receipts from the Mobility Tax

imposed in the Metropolitan Commuter Transportation District are included in All Funds revenues.

*Less than 0.1%

Source: All Funds Revenues reported as receipts for 2009-2010. NYS Mid-Year Financial Plan Update 2010-11 through 2013-14,

November 1, 2010, pp. 46-58.

ix Exhibit 2: Dedicated Fund Tax Receipts (Millions of $), 2009-2010

FUND

Value

Total Tax Receipts: Dedicated Funds*

$22,416

Special Revenue Funds

8,805

School Tax Relief Fund (STAR)

3,420

Personal Income Tax

3,420

Dedicated Mass Transportation Trust Fund

655

Petroleum Business Tax

363

Motor Fuel Tax

105

Motor Vehicle Fees

187

MTA Financial Assistance Fund

1,545

MCTD Payroll Tax

1,384

Motor Vehicle Fees

121

Auto Rental Tax

26

Taxicab Surcharge

14

Mass Trans. Operating Assistance Fund

1,796

Corporate Surcharges

926

Corporation Franchise Tax

461

Corporation and Utilities Tax

139

Insurance Tax

133

Bank Tax

193

Other

870

Sales and Use Tax

662

Petroleum Business Tax

135

Corporation and Utilities Tax– Sections 183 & 184

73

HCRA Resources Fund

1,348

Cigarette Tax

898

Syrup Excise Tax

450

Other Special Revenue Funds

41

Motor Vehicle Fees

41

Debt Service Funds

11,563

Revenue Bond Tax Fund

8,806

Personal Income Tax

8,806

Clean Water/Clean Air Fund

256

Real Estate Transfer Tax

256

Local Government Assistance Tax Fund

2,501

Sales and Use Tax

2,501

Capital Projects Funds

2,048

Dedicated Highway and Bridge Trust Funds

1,849

Petroleum Business Taxes

621

Motor Fuel Tax

396

Motor Vehicle Fees

621

Highway Use Tax

140

Transmission Tax

18

Auto Rental Tax

53

Environmental Protection Fund

199

Real Estate Transfer Tax

199

*Total does not include proprietary funds or fiduciary funds.

Source: Estimates as reported in 2010-2011 Executive Budget, Economic and Revenue Outlook, p. 384.

x Exhibit 3: Common Issues and Concerns Related to Major NYS Taxes

Electronic

Commerce

Regulatory

Reforms

Tax

High Taxes

Personal Income

Sales/Use

Cigarette

Alcoholic

Beverage

Motor Fuels

Highway Use

Auto Rental

9A Corporation

Franchise

Utilities

Insurance

Bank

Petroleum

Real Property

Transfer

Estate

Does not include taxes that account for less than 0.1% of NYS tax revenues.

Lack of

Transparency

NYS Taxing Same

Base as Local

Government

Tax Expenditures

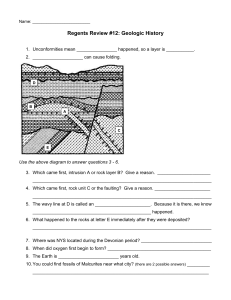

xi Personal Income Tax

1.0 PERSONAL INCOME TAX

1.1 Overview

New York State adopted the Personal Income

Tax (PIT) in 1919 under Article 22 of the State

Tax Law. In FY 2010, the PIT generated $34.8

billion, accounting for 60.3% of NYS tax

revenues and 27.4% of all State revenues. Of the

$34.8 billion, 65.3% was deposited in the State

General Fund, 9.7% in the School Tax Relief

Fund (STAR) and 25.0% in the Revenue Bond

Tax Fund (RBTF).1

Taxable Income Sources. Residents are taxed

on all sources of income; non-residents are taxed

on income attributable to NYS sources. Income

sources for residents and non-residents include

wages, salaries, divided income and income

from business entities in which the taxpayer

performs services or holds an interest.

1.2 The NYS Personal Income Taxpayer

The State PIT is imposed on the taxable income

of NYS resident or non-resident individuals,

estates and trusts.

Non-residents accounted for 10.2% of State

PIT tax returns and 15.5% of PIT liability in

2007. 2

Tax payments from high-income filers represent

a substantial portion of total PIT revenues. In

FY2010, an estimated 33% of PIT liability was

attributable to taxpayers with NYS Adjusted

Gross Income of $1,000,000 and above and 20%

to taxpayers with NYAGI of $200,000 up to

$1,000,000. As shown in Table 1.1, of total tax

returns, 0.4% and 2.6% were filed by these two

groups of taxpayers, respectively.

Table 1.1: NYS Personal Income Taxes, 2010

Percent of Total

Income

Tax

Tax

Liability Returns

$0-$50,000

4.6%

61.0%

50,000-100,000

23.3

26.4

100,000-200,000

18.6

9.7

200,000-1,000,000

20.2

2.6

1,000,000 & above

33.3

0.4

NYS

AGI

17.5%

28.5

18.6

14.7

20.7

Note: Percentages may not add to 100% due to rounding.

Source: Estimates by NYS Division of the Budget in 2010-2012

Executive Budget, Economic and Revenue Outlook, p. 192.

For taxpayers who are sole proprietors, the

PIT is imposed on business net earnings.

For taxpayers who are members of a

partnership, the PIT is imposed on their

distributive share of partnership income.

Partnerships, including limited liability

companies treated as partnerships, with

NYS-source gross income of $1 million or

more must pay a filing fee ranging from $25

to $4,500.

Limited Liability Companies are classified

and taxed as partnerships for purposes of the

New York State PIT unless they elect to be

taxed as a corporation.

S Corporation income is passed through to

individual shareholders and subject to the

PIT.

Filing Status. The State has 5 filing statuses,

e.g., married filing jointly with 7 tax brackets for

tax years 2009-2011 – 5 brackets are in the

permanent tax structure. The two temporary

brackets were added at the top end of the income

range with the highest rate set at 8.97% on

taxable income in excess of $500,000 for all

filers (see Exhibit 1.1).

The Mobility Tax. Effective 2009, NYS has

imposed the Metropolitan Commuter

Transportation Mobility Tax, a $0.34/$100 payroll tax on most employers and self-employed

individuals doing business in NYC and the other

7 counties in the MCTD: Dutchess, Nassau,

Orange, Putnam, Rockland, Suffolk and

Westchester. NYS distributes the mobility tax

revenues to the MTA.

1-­‐1 For individuals, the tax is imposed on net

earnings from self-employment allocated to the

MCTD for the tax year.3 Partners – including

members of LLCs treated as partnerships for

purposes of the Federal Income Tax – are

subject to the 0.34% tax on net earnings

allocated to the MCTD. For S Corporations, the

tax is imposed on the payroll of workers who are

employed in the MCTD; distributions to

owners/shareholders are not subject to the

Mobility Tax.

1.3 The NYS Personal Income Tax Base

The NYS Personal Income Tax base is derived

from the taxable income of residents and nonresidents with State-source income. As shown in

Figure 1.1, the starting point for computing NYS

Personal Income Tax liability is Federal

Adjusted Gross Income (FAGI) as reported on

Federal individual income tax returns. FAGI is

then adjusted to arrive at NYS Adjusted AGI

(NYAGI).

Once NYAGI is determined, taxpayers subtract

NYS deductions and exemptions from this value

to determine NYS taxable income – the base for

calculating NYS tax liability.

Deductions. New York State PIT filers may

deduct either the NYS-defined standard

deduction or State-defined itemized deductions

from their NYAGI. Taxpayers taking the

standard deduction for Federal purposes must

use the NYS standard deduction in calculating

their taxable income for State PIT purposes. The

standard deduction is $7,500 for single filers and

$15,000 for joint filers. Figure 1.1: Calculating NYS Personal

Income Tax Liability

Federal Adjusted Gross Income

Plus

New York State Add-ons

Minus

New York State Subtractions

Equals

New York State Adjusted Gross Income

Minus

NYS Deductions and Exemptions

Equals

New York State Taxable Income

Multiplied by

NYS Tax Rates

Equals

NYS PIT Liability Before Credits

Minus

NYS Tax Credits

Equals

Certain income items not taxed by the Federal

government are taxed by NYS; these are added

back to Federal AGI to calculate NYAGI. Other

items subject to Federal taxation are not taxed

by NYS; these are subtracted from Federal AGI

to calculate NYAGI.

Add-backs to FAGI include state, local and

foreign income taxes deducted for Federal

income tax purposes, interest on bonds

issued by other states and their localities,

and certain retirement and flexible benefits

paid to NYC and NYS employees. Other

add-backs result from NYS decoupling from

the Federal tax code, e.g., depreciation

allowances. 4

Subtractions from FAGI include interest

income on U.S. government bonds, taxable

social security payments, all Federal, NYS

and local government pension income,

qualifying private pension and annuity

income up to $20,000. NYS residents are

also permitted to subtract their contributions

of up to $5,000 ($10,000 for joint filers) per

year to the NYS College Choice Tuition

Savings Program.

NYS PIT Liability Deductions for taxpayers who itemize are the

same as those allowed for Federal income tax

purposes with certain modifications. These

include adding back State income taxes which

are deductible for Federal but not for State tax

purposes. Additional modifications are applied

to higher income filers.

For single NYS PIT filers with NYAGI over

$100,000, and for married filers with

NYAGI over $200,000, deductions are

1-­‐2

limited to 75% of their modified Federal

itemized deductions.

For all filers with NYAGI greater than

$525,000 up to $1 million, deductions are

limited to 50% of their modified Federal

itemized deductions.

For all filers with NYAGI over $1 million,

itemized deductions are limited to 50%

percent of the charitable deductions taken

on the Federal return.

In Tax Years 2010 to 2012, for all filers with

NYAGI over $10 million, itemized

deductions are limited to 25% of charitable

contributions taken on their Federal return.

Exemptions. An exemption of $1,000 per

dependent is provided for purposes of

determining State PIT taxable income. Unlike

the Federal government, the State does not

permit an exemption for the taxpayer or spouse.

Tax Liability. As shown in Figure 1.1, State PIT

liability is calculated by (1) multiplying NYS

taxable income by the appropriate tax rates and

(2) subtracting the dollar value of tax credits

allowable by NYS, where applicable.

Credits reduce tax liability by an amount equal

to the value of the credit in contrast to

exemptions and deductions which reduce taxable

income, i.e. the base upon which tax liability is

determined.

Table 1.2: Highest Value Credits Taken Against NYS

Personal Income Tax Liability, Estimated FY2010

Percent of

FY2010 PIT

Credit

Value in Millions Revenues

Earned Income

$825

2.3%

Credit

Empire State

655

1.9

Child Credit

Brownfield*

465

1.3

Child and

300

0.9

Dependent Care

Credit

College Tuition

224

0.6

Credit

Qualified Empire

170

0.5

Zone Credits**

*Credit taken by sole proprietors, partners in partnerships, including

LLCs and shareholders in State S Corporations

**Effective 7/1/10, Empire Zone Credits have been replaced by

credits under the NYS Excelsior Jobs Program.

Source: Estimates from 20th Annual NYS Tax Expenditure Report,

pp. 28-30.

1.4

Trends in NYS Personal Income Tax

Revenues

The FY2010 revenues pictured in Figure 1.2

were 50% above FY2000 revenues in current

dollars. In constant dollars they were 17% above

FY2000 but 8% below the FY2008 peak year

level.

New York State provides credits to achieve three

different policy objectives. They are:

To reduce the tax burden for taxpayers with

incomes below a certain level.

To promote certain taxpayer behavior.

To encourage economic development/capital

investment. These credits are provided to

sole proprietors, partnership members and

other business owners who are subject to the

PIT rather than one of the NYS business

income taxes.

Certain PIT credits are refundable which means

that if the value of the credit exceeds tax

liability, the excess is refunded to the taxpayer.

The values of the most expensive PIT tax

expenditures in FY 2010 are shown in Table 1.2.

All PIT credits are listed in Exhibit 1.3.

Figure 1.3 shows that PIT revenues are sensitive

to changing economic conditions. The increase

in PIT rates to offset declining tax collections

prevented even larger revenue fluctuations than

those that actually occurred in several years

including 2010.

1-­‐3

The combined NYC/NYS top PIT tax rate is

the highest in any jurisdiction in the U.S.

(see Exhibits 1.1 and 1.2)

Yonkers. Yonkers levies an income tax on

residents at a rate of 10% of their NYS tax

liability after accounting for non-refundable

credits. It imposes an earnings tax on nonresidents at a rate of 0.5% of wages/selfemployment earnings in Yonkers, after an

exclusion of $3,000 that phases out when

earnings exceed $30,000.

1.5 History of the NYS Personal Income Tax

In 1919, NYS became the 7th state to enact some

type of personal income tax. In 1959, the State

PIT law was adopted defining NY income

according to Federal law. Structural reforms that

change the definition of Federal taxable income

(e.g., deductions) have a direct impact on the

NYS definition of taxable income unless the

State makes modifications to its tax. Changes to

Federal tax rates, however, do not directly

impact the State since its own tax structure is

used to calculate NYS tax liability (see Figure

1.1, p. 2). Major legislative changes to the PIT

since 1980 are summarized in Exhibit 1.5.

1.6 The Personal Income Tax in NYS Local

Jurisdictions

NYC and Yonkers are the only local governments

in NYS with statutory authority to levy a Personal

Income Tax. Both taxes are administered by the

NYS Department of Taxation and Finance and

reported by taxpayers in a separate section of their

State Personal Income Tax returns.

New York City. The New York City PIT is

imposed on the taxable income of resident

individuals, estates, and trusts. No City PIT is

imposed on non-residents with the exception of

certain employees of the NYC government who

are required to pay an amount equivalent to the

PIT they would pay if they were City residents. 1.7 The Personal Income Tax in Other States

Forty-one states plus the District of Columbia

impose some type of broad-based income tax

(see Exhibit 1.4); in two states tax imposed

solely on dividends and interest income. Among

the 41 states imposing the tax, 15 give all or

certain local governments the option to impose a

similar tax. Philadelphia is the only local

government with a higher tax rate than NYC –

but it has a lower combined city/state rate.

1.8 Issues and Concerns

High Tax Rates. The two new marginal PIT

rates imposed by the State for tax years 20092011 bring the combined NYC/NYS top

marginal rate to 12.62%. This is the highest

combined state/city tax rate imposed in any

jurisdiction in the nation and provides an

incentive for high income earners living in NYC

to relocate especially to nearby states with lower

taxes.

Tax Expenditures. In FY2010, the total revenue loss to NYS associated with tax

expenditures related to the PIT was $10.8

billion.5 The loss resulted from:

exclusions taken by taxpayers in modifying

Federal AGI to arrive at NYAGI;

deductions and exemptions subtracted from

NYAGI to arrive at NYS taxable income

(the base for calculating tax liability); and

subtraction of the dollar value of credits

from tax liability to determine the amount of

taxes owed to NYS. The estimated value of

tax expenditures associated with credits

1-­‐4

against the PIT in FY2010 was $3.0 billion

– 8.8% of FY2010 PIT revenues. All PIT

credits are listed in Exhibit 1.3.

Many PIT credits are refundable which

means that if the value of the credit exceeds

tax liability, the excess is refunded to the

taxpayer by NYS. In FY2010, the estimated

value of refunded credits was $2.8 billion.

Transparency. The 94-page instruction booklet

issued to taxpayers with the PIT tax form

demonstrates how complicated the tax is. Its

complexity results in a lack of transparency, an

important indicator of a good tax.6 The booklet

contains instructions for three tax forms, several

tables to assist the taxpayer in calculating tax

liability and instructions for claiming tax credits

and deductions.

Several components of the PIT contribute to its

complexity. These include the many add-backs

and subtractions from Federal Adjusted Gross

Income to determine NYS Adjusted Gross

Income and the close to 40 credits that can be

used by taxpayers to reduce tax liability –

assuming taxpayers understand their eligibility

for them. Special rules that apply to high income

taxpayers also contribute to the complexity of

the PIT.

Endnotes

1

Based on estimates for 2010 published in 2010-11

NYS Executive Budget. Economic and Revenue

Outlook, p. 177. http://publications.budget.state.

ny.us/eBudget1011/economicRevenueOutlook/econo

mic RevenueOutlook.pdf

2

2007 is the latest year for which these data are

available. Generally, non-residents can claim a credit

against income tax liability in their home state for

NYS taxes paid.

3

The tax does not apply if the individual’s allocated

net earnings from self employment are $10,000 or

less for the tax year.

4

Because the calculation of NYAGI starts with FAGI,

modification of FAGI will impact NYAGI. NYS

must pass legislation if it does not want the Federal

provisions to apply to NYS/NYC tax calculations.

This legislative action is referred to as decoupling.

5

NYS 20th Annual Report on Tax Expenditures

http://publications.budget.state.ny.us/eBudget1011/fy

1011ter/TaxExpenditure10-11.pdf p. 29.

6

American Institute of Certified Public Accountants

Guiding Principles for Tax Law Transparency.

Special instructions for taxpayers with annual

incomes in excess of $100,000 are provided in

the PIT instruction booklet. They require most

taxpayers in this income bracket to multiply

taxable income by a flat tax rate rather than

applying the progressive rate structure used by

other taxpayers.

1-­‐5 Exhibit 1.1: NYS Personal Income Tax Rates by Filing Status, Tax Year 2010

Rates

4%

4.5%

5.25%

5.9%

6.85%

7.85%*

8.97%*

Single/Married

Filing

Separately

$8,000 or less

Over $8,000 to $11,000

Over $11,000 to $13,000

Over $13,000 to $20,000

Over $20,000 to $200,000

Over $200,000 to $500,000

Over $500,000

New York State Taxable Income

Head of Household Filer

Married Filing Jointly**

$11,000 or less

Over $11,000 to $15,000

Over $15,000 to $17,000

Over $17,000 to $30,00

Over $30,000 to $250,000

Over $250,000 to $500,000

Over $500,000

$16,000 or less

Over $16,000 to $22,000

Over $22,000 to $26,000

Over $26,000 to $40,000

Over $40,000 to $300,000

Over $300,000 to $500,000

Over $500,000

*Two top rates are temporary for tax years 2009-2011. ** Same rates apply to qualified surviving spouse filers.

Source: New York State Personal Income Tax Return IT150/2010

Exhibit 1.2: NYC Personal Income Tax Rates by Filing Status, Tax Year 2010*

New York City Taxable Income

Rates

Head-of Household-Filer

Married Filing Jointly**

2.907%

3.534%

Single/Married Filing

Separately

$12,000 or less

Over $12,000 to $25,000

$14,400 or less

Over $14,400 to $30,000

$21,600 or less

Over $21,600 to $45,000

3.591%

Over $25,000 to $50,000

Over $30,000 to $60,000

Over $45,000 to $90,000

3.648%

Over $50,000

Over $60,000

Over $90,000

*Includes 14% additional tax (also referred to as the surcharge). For example, the top 3.648% base rate without the 14% additional tax is 3.2%.

**Same rates apply to surviving resident spouse filers.

Source: New York State Personal Income Tax Return IT150/2010

1-­‐6 Exhibit 1.3: NYS Personal Income Tax Credits, Estimated FY2010 Value (millions of $)

Tax Credit Category

Reducing Tax Burden on Filers with

Certain Income Characteristics

Encouraging Certain Taxpayer

Behavior

Economic Development/Capital

Investment Credits

Credit

Household Credit

Earned Income Credit*

Real Property Tax Credit (Circuit Breaker)*

Value

93

825

30

Child and Dependent Care Credit*

300

Empire State Child Credit*

655

Enhanced State Earned Income Tax Credit for Certain

Non-Custodial Parents *

College Tuition Credit*(includes value for itemized

deductions)

Rehabilitation of Historic Properties Credit

Historical Homeownership Rehabilitation Credit

Clean Heating Fuel Credit *

Long-term Care Insurance Credit

3

224

5

5

0.3

75

Conservation Easement Credit *

2

Solar Energy System Equipment Credit

**

Green Building Credit

0.2

Volunteer Firefighters and Ambulance Workers Credit *

14

Security Training Tax Credit*

0.1

Low-Income Housing Credit

Investment Credit

Investment Credit for Financial Services Industry

Qualified Empire Zone Credit*

Empire Zone and Zone Equivalent Areas Tax Credit***

20

24

0.4

170

45

Employment of Persons with Disabilities Credit

Accessible Taxicabs for Individuals with Disabilities

Credit

Purchase of an Automated External Defibrillator Credit

0.1

0.1

Qualified Emerging Technology Companies Credits

(QETC)

QETC Capital Tax Credit

QETC Employment Credit*

QETC Facilities, Operations and Training Credit*

Empire State Film Production Credit *

0.1

1

0.2

5

8

Brownfields Tax Credit *

465

Alternative Fuel Credit

**

Empire State Commercial Production Credit*

6

Bio-fuel Production Credit *

10

Farmers’ School Property Tax Credit*

30

*Refundable credit **Less than $100,000 in tax expenditures ***Refundable for new businesses only Note: Accumulation Distribution Credit ($0.1million), Nursing Home Assessment Tax Credit ($14 million) and the Special Additional Mortgage Recording Tax Credit ($20 million) not included. Source: 20th Annual Report on New York State Tax Expenditures, New York State Division of the Budget and Department of Taxation and Finance , Table 4. 1-­‐7 Exhibit 1.4: State Personal Income Tax Rates, 2010*

State

Alabama

Arizona

Arkansas

California

Colorado

Connecticut

Delaware

Georgia

Hawaii

Idaho

Illinois

Indiana

Iowa

Kansas

Kentucky

Louisiana

Maine

Maryland

Massachusetts

Michigan

Minnesota

Mississippi

Missouri

Montana

Nebraska

New Hampshire

New Jersey

New Mexico

New York

North Carolina

North Dakota

Ohio

Oklahoma

Oregon

Pennsylvania

Rhode Island

South Carolina

Tennessee

Utah

Vermont

Virginia

West Virginia

Wisconsin

Dist. of Columbia

Tax Rate

Range

2.0-5.0

2.59-4.54

1.0-7.0

1.25-9.55

+1%>$1 mill

4.63

3.0-6.5

Brackets

3

5

6

6

Personal Exemptions /Credits

$300/dependent; $1,500/single filer; $3,000/married filer

$2,300/dependent;$2,100/single filer; $4,200/ married filer

Tax credit: $23/dependent; $23/single filer; $46/married filer

Tax credit: $98/dependent; $98/single filer; $196 married filer

None

Maximum exemption $13,000, decreasing as income increases; phased out at AGI of

$61,000

2.2-6.95

6 Tax credits: $110/ dependent; $110/single filer; $220/married filer;

1.0-6.0

6 $3,000/dependent; $2,700 single filer; $5,400 married filer

1.4-11.0

12 $1,040/dependent; $1,040/single filer; $2,080/ married filer

1.6-7.8

8 $3,650/dependent; $3,650/single filer; $7,300/married filer**

3.0

1 $2,000/dependent and single filer; $4,000/married filer

3.4

1 $1,000/dependent; $1,000 /single filer; $2,000 /married filer

0.36-8.89

9 Tax credits: $40/dependent; $40/single filer; $80/married filer

3.5-6.45

3 $2,250/dependents; $2,250/single filer; $4,500/married filer

2.0-6.0

6 Tax credit: $20/dependent; $20/single filer; $40/married filer

2.0-6.0

3 Combined personal exemption and standard deduction: $1,000/dependent; $4,500/

single filer; $9,000 married filer

2.0-8.5

4 $2,850/dependent; $2,850/single filer; $5,700/married filer

2.0-6.25

8 $2,400/dependent; $2,400/single filer; $4,800/married filer

5.3

1 $1,000/dependent; $4,400/single filer; $8,800/married filer

4.35

1 $3,300/dependent, $3,300/single filer, $6,600/married filer

5.35-7.85

3 $3,650/dependent; $3,650/single filer; $7,300/married filer**

3.0-5.0

3 $1,500/dependent; $6,000/single filer; $12,000/married filer

1.5-6.0

10 $1,200/dependent; $2,100/single filer; $4,200/married filer

1.0-6.9

7 $2,110/dependent; $2,110/single filer, $4,200/married filer

2.56-6.84

4 Tax Credit: $118/dependent; $118/single filer; $236/married filer

State Income Tax Limited to Dividends and Interest Income

1.4-10.75

8 $1,500/dependent; $1,000/single filer; $2,000/married filer

1.7-4.9

4 $3,650/dependent; $3,650/single filer; $7,300/married filer**

4.0-8.97

7 $1,000 /dependent; no exemption for taxpayer or spouse

6.0-7.75

3 $3,650/dependent; $3,650/single filer; $7,300/married filer**

1.84-4.86

5 $3,650/dependent; $3,650/single filer; $7,300/married filer**

0.618-6.24

9 $1,550/dependent; $1,550/single filer; $3,100/married filer

0.5-5.5

7 $1,000/dependents; $1,000/single filer; $2,000/married filer

5.0-11.0

5 Tax credit: $176/dependent; $176/single filer; $352/married filer

3.07

1

None

3.8-9.9

5 $3,650/dependent, $3,650/single filer, $7,300/married filer**

0.0-7.0

6 $3,650/dependent; $3,650/single filer; $7,300 married filer**

State Income Tax Limited to Dividends and Interest Income

5.0

1 Tax credit: 75% of Federal personal exemption amounts phased out above $12,000 in

income ($24,000 for joint returns)

3.55-8.95

5 $3,650/dependent; $3,650/single filer; $7,300/married filer**

2.0-5.75

4 $930/dependent; $930/single filer; $1,860/married filer

3.0-6.5

5 $2,000/dependent; $2,000/single filer; $4,000/ married filer

4.6-7.75

5 $700/dependent; $700/single filer; $1,400/married filer

4.0-8.5

3 $1,675/dependent; $1,675/single filer; $3,350/married filer

1

3

Note: No PIT imposed in Alaska, Florida, Nevada, South Dakota, Texas, Washington, and Wyoming.

*Rates as of 1/1/2010. Rates do not include local government taxes.

**Exemptions as provided for Federal income tax purposes.

Source: Federation of Tax Administrators, State Individual Income Taxes.

1-­‐8 Exhibit 1.5: Major NYS Legislative Actions Affecting the NYS Personal Income Tax, 1980-2010

Year

Action

1981

Commission on Modernization and Simplification of the Tax Law (also known as the Legislative Tax Study

Commission) created to suggest strategies for reforming the State Tax Law.

Three-year tax reduction plan enacted which reduced PIT liability for all income groups, especially low and

middle income taxpayers.

NYS Tax Reform and Reduction Act passed in response to Federal Tax Reform Act of 1986 (TRA). TRA

decreased rates and broadened the federal income tax base by limiting certain exclusions and by repealing

certain itemized deductions and tax preferences. The NYS reform known as TRRARA contained provisions to

phase in a reduction in the number of basic tax rates from 12 in 1986 to 5 by 1989 and removed a large number

of low-income taxpayers from the tax rolls by increasing the State’s standard deduction.

1990 rates and standard deduction frozen at 1989 levels. Rates and standard deduction amounts were frozen

again in 1992, 1993, 1994, extending full phase in until 1997.

Supplemental tax enacted to recapture the benefit of the State’s graduated income tax rates for taxpayers with

NYAGI in excess of $100,000.

Limited Liability Companies (LLCs) established to be taxed under PIT.

1985

1987

1990

1991

1993

1995

1997

Phased-in reduction of the top tax rate from 7.875% in 1994 to 6.85% in 1997. Changed from a five-bracket

structure in 1994 to a four-bracket structure in 1995, then back to five in 1996 and later. Income level of top

bracket increased from $26,000 in 1994 to $40,000 in 1997 for married, filing jointly. Excess Deductions

Credit enacted for TY 1995 to offset potential tax increases for low and middle income taxpayers.

School Tax Relief (STAR) Program created to provide Property Tax relief financed by PIT receipts

2002

Tax amnesty program adopted for one year.

2003

2007

Two new tax brackets added for 2003, 2004, and 2005 applicable to high-income taxpayers. Temporarily

increased LLC fees for 2003 and 2004.

Required certain Federal S corporations to become New York S corporations.

2008

Restructured and reformed fees and minimum tax imposed on LLCs and S and C corporations.

2009

Enacted three-year surcharge on high income taxpayers. Extended PIT to cover sale of partnership interest by

non-residents when 50% or more of partnership’s real property is located in NYS. Limited itemized deduction

for taxpayers with incomes over $1 million. Repealed certain components of the STAR rebate program.

Imposed fees on non-LLC partnerships with NY-source income at above $1 million at same rates applicable to

LLCs.

2010

Further limited use of itemized deduction by taxpayers with NYAGI over $10 million to 25% of charitable

contributions on the Federal tax return for tax years 2010-2012.

Note: Exhibit 1.5 does not include changes to PIT deductions, exemptions or most credits.

Sources: Unpublished information supplied to author by NYS Assembly Ways & Means Committee. 2010-11 NYS Executive

Budget, Economic and Revenue Outlook.

1-­‐9 Sales/Use Tax

2.0 SALES/USE TAX

2.1 Overview

New York State adopted the State-wide Sales

and Compensating Use Tax in 1965 under

Article 28 of the State Tax Law. The Sales Tax

is imposed on the sale of most commodities

purchased in NYS and on enumerated services

provided in the State. The Compensating Use

Tax (Use Tax) is imposed on purchases made

outside of the State and brought into it for use.

In FY2010, the NYS Sales/Use Tax yielded

$10.5 billion including the $0.6 billion in

revenues from the 0.375% tax imposed in the

Metropolitan Commuter Transportation District

(MCTD). The $10.5 billion accounted for 18%

of NYS tax revenues and 8% of total State

revenues.

Of the total $10.5 billion in Sales/Use Tax

revenues, 70.3% was deposited in the NYS

General Fund, 6.2% in the State’s Mass

Transportation Operating Assistance Fund and

23.4% in the Local Government Assistance Tax

Fund (LGATF).1 LGATF receipts in excess of

debt service requirements on Local Government

Assistance Corporation bonds are transferred to

the General Fund.2

2.2 The NYS Sales/Use Taxpayer

Sales by the retail trade sector are the primary

source of NYS Sales/Use Tax revenues,

accounting for 44% of all taxable sales in 20072008. This was more than twice the 21%

generated by the services sector (including food

and accommodations), the second largest source,

and four times the 10% attributable to the

wholesale trade sector, the third largest source. 3

Vendors generally act as the tax collectors for

the State but for some purchases the individual

consumer may be liable for the tax. The

responsibility for Sales/Use Tax collections

depends on the venue in which the purchase is

made.

When a taxable purchase is made in-person

in NYS, the Sales Tax is collected by the

vendor who is required to remit the taxes

collected on the sale to the State. When the

purchase of a taxable commodity is made

remotely – by mail, over the phone, from a

catalog, or on-line – and the tax is not

collected by the vendor, the customer is

liable for remitting the Use Tax to NYS.4

When a purchase is made outside of the

State and shipped to a NYS address, the

vendor is responsible for collecting the Use

Tax if it has nexus to the State. If the vendor

does not have nexus, the customer is

responsible for paying the Use Tax to NYS.

When a taxable purchase is made outside

NYS and the out-of-state Sales Tax rate is

less than the tax rate in NYS, a Use Tax on

the difference between the two rates must be

paid by the customer.

Nexus. The term nexus in tax law describes a

situation in which a business has presence in a

jurisdiction and is thus required to collect taxes

for sales within that jurisdiction. In NYS and

elsewhere in the U.S., the determination of

nexus is based on two U.S. Supreme Court

decisions: National Bellas Hess v. Department

of Revenue in 1967 and Quill v. North Dakota in

1992.5

The Court ruled in Bellas Hess and reaffirmed in

Quill that a vendor is exempt from collecting the

Sales/Use tax in a jurisdiction in which it does

not have an identifiable physical presence. In

both cases, the Court acted on its interpretation

of the potential adverse impact on interstate

commerce if vendors were required to know the

rates and range of taxable items in every taxing

jurisdiction. Although both Bellas Hess and

Quill dealt with catalog mail orders, the Court’s

decisions have been extended to apply to ecommerce sales.

The rapid growth of e-commerce sales has

increased the complexity and the importance of

defining nexus. NYS and local government

losses of Sales/Use Tax revenues in FY 2010

2-­‐1 related to untaxed e-commerce sales is estimated

at $655 million.6

State Actions to Address the Nexus Issue. In

Quill, the Court acknowledged the power of

Congress to overturn its decision. In the absence

of any congressional action, the states have tried

to reconcile differences in their Sales/Use tax –

the problem identified in the Quill decision –

primarily through the Streamlined Sales Tax

Project (SSTP). The project, organized in 2000

by representatives from state legislatures, local

governments, and the private sector, has been an

attempt to minimize differences among state

sales taxes.

In 2002, the SSTP group approved the Uniform

Sales and Use Tax Administration Act, known

as the Streamlined Sales Tax and Use

Agreement (SSUTA). The Agreement combines

uniform

administration

procedures

with

simplification measures, but does not mandate

any actions by the states. By signing onto the

SSUTA, states agree to revise their Sales Tax

process and to make changes to their tax laws,

rules and regulations. Currently 20 states are full

members in compliance with the SSUTA; 3 are

associate members.7

Although NYS was party to development of the

SSUTA, it has not become a signatory to it. To

do so, the State would have to make extensive

revisions to its Sales Tax law including changing

its exemptions for telecommunication services,

clothing, drugs and medical equipment.

Addressing Nexus in NYS. In 2008, NYS

amended its Sales/Use Tax Law to address the

issue of physical presence and nexus particularly

as it relates to certain Internet vendors. The

amendment expands the State’s definition of

nexus to include companies that have no

physical presence other than in-State affiliates.

Referred to as the Amazon Law, the State’s

amendment is directed at Internet vendors using

affiliates to promote in-state sales. These

affiliates, or independent in-state website

owners, place a link to the Internet vendor on

their own websites and earn a commission on

sales made from referrals. Amazon.com challenged the amendment in the NYS Supreme

Court arguing that its affiliates are independent

contractors who are advertisers, and that

Amazon.com does not have nexus in New York.