SCHRES-05415; No of Pages 4

Schizophrenia Research xxx (2013) xxx–xxx

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect

Schizophrenia Research

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/schres

Review

Structure of the psychotic disorders classification in DSM 5

Stephan Heckers a,⁎, Deanna M. Barch b, Juan Bustillo c, Wolfgang Gaebel d, Raquel Gur e,

Dolores Malaspina f, Michael J. Owen g, Susan Schultz h, Rajiv Tandon i, Ming Tsuang j,

Jim Van Os k, William Carpenter l

a

Department of Psychiatry, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA

Departments of Psychology, Psychiatry and Radiology, Washington University, St. Louis, MO, USA

Department of Psychiatry, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, USA

d

Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Medical Faculty, Heinrich-Heine-University, Duesseldorf, Germany

e

Departments of Psychiatry, Neurology and Radiology, Perlman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA

f

Department of Psychiatry, New York University, New York, NY, and New York State Office of Mental Health, Creedmoor Psychiatric Center, Queens, NY, USA

g

MRC Centre for Neuropsychiatric Genetics and Genomics and Neuroscience and Mental Health Research Institute, Cardiff University, Cardiff, Wales

h

Department of Psychiatry, University of Iowa School of Medicine, Iowa City, IA, USA

i

Department of Psychiatry, University of Florida Medical School, Gainesville, FL, USA

j

Department of Psychiatry, UCSD, CA, USA

k

Maastricht University Medical Centre, South Limburg Mental Health Research and Teaching Network, EURON, Maastricht, The Netherlands

l

Department of Psychiatry, Maryland Psychiatric Research Center, Baltimore, MD, USA

b

c

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Article history:

Received 23 February 2013

Received in revised form 21 April 2013

Accepted 26 April 2013

Available online xxxx

Keywords:

Schizophrenia

DSM

Nosology

Diagnosis

Psychotic disorders

a b s t r a c t

Schizophrenia spectrum disorders attract great interest among clinicians, researchers, and the lay public.

While the diagnostic features of schizophrenia have remained unchanged for more than 100 years, the mechanism of illness has remained elusive. There is increasing evidence that the categorical diagnosis of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders contributes to this lack of progress. The 5th edition of the Diagnostic

and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) continues the categorical classification of psychiatric disorders since the research needed to establish a new nosology of equal or greater validity is lacking. However,

even within a categorical system, the DSM-5 aims to capture the underlying dimensional structure of psychosis. The domains of psychopathology that define psychotic disorders are presented not simply as features of

schizophrenia. The level, the number, and the duration of psychotic signs and symptoms are used to demarcate psychotic disorders from each other. Finally, the categorical assessment is complemented with a dimensional assessment of psychosis that allows for more specific and individualized assessment of patients. The

structure of psychosis as outlined in the DSM-5 may serve as a stepping-stone towards a more valid classification system, as we await new data to redefine psychotic disorders.

© 2013 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Schizophrenia is a classic psychiatric diagnosis. The defining features have remained unchanged for more than 100 years (Heckers,

2011). However, emphasis has shifted from avolition and dissociation

towards reality distortion (Fischer and Carpenter, 2009). The diagnosis attracts great interest among clinicians, researchers, and the lay

public. Schizophrenia is associated with significant bias and stigma,

leading some to ask for the removal of the word from diagnostic manuals (Umehara et al., 2011). But even those who prefer a different

name do not doubt that schizophrenia is real (Lieberman and First,

2007).

⁎ Corresponding author at: Department of Psychiatry, 1601 23rd Avenue South, Room

3060, Nashville, TN 37212, USA. Tel.: +1 615 322 2665.

E-mail address: stephan.heckers@vanderbilt.edu (S. Heckers).

Despite sustained effort, the mechanism of schizophrenia has remained elusive. There is increasing evidence that the categorical diagnosis of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders contributes

to this lack of progress (Heckers, 2008). The current diagnoses do

not accurately capture the considerable variability of symptom profile, response to treatment, and most importantly, social function

and outcome. As a result, there is increasing pressure to change the

structure of psychiatric nosology, in order to accelerate better treatment, prevention, and ultimately cure (Cuthbert and Insel, 2010;

Insel, 2010).

The 5th edition of the DSM does not represent such a paradigm shift.

While there was considerable hope to replace the categorical diagnosis

of psychiatric disorders, the research needed to establish a new nosology of equal or greater validity is lacking (Hyman, 2007; Kupfer and

Regier, 2011). So far, the mechanistic models of brain and behavior provided by systems and basic neuroscience research have not been adequately tested in clinical settings. Nonetheless, despite the inherent

0920-9964/$ – see front matter © 2013 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2013.04.039

Please cite this article as: Heckers, S., et al., Structure of the psychotic disorders classification in DSM 5, Schizophr. Res. (2013), http://dx.doi.org/

10.1016/j.schres.2013.04.039

2

S. Heckers et al. / Schizophrenia Research xxx (2013) xxx–xxx

conservative bias, the DSM-5 chapter “Schizophrenia Spectrum and

Other Psychotic Disorders” (referred to as Schizophrenia Spectrum for

short in the rest of this article) departs from the previous edition in several respects. Even within the established categorical system, we want

to capture the underlying dimensional structure of psychosis. To that effect, we employ the terms domains, gradients, and dimensions. There

are five domains of psychopathology that define psychotic disorders.

The level of psychosis, the number of symptoms, and the duration of

psychosis are the gradients that have been used to demarcate psychotic

disorders from each other and continue to be used for the same purpose

in DSM-5. The dimensions refer to a structure of psychosis that is not

simply categorical but allows for much greater flexibility in the assessment of psychopathology, including aspects that are not considered as

defining domains of psychosis.

Here, we describe the structure of the chapter on “Schizophrenia

Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders” in the DSM-5. We review

the domains of psychopathology that define psychosis, clarify the status of catatonic features, and describe the greater emphasis on dimensions incorporated into the DSM-5.

2. Domains of psychopathology

The most visible change in the schizophrenia spectrum chapter is

the less prominent position of schizophrenia. DSM-IV puts schizophrenia front and center. All the classic features of psychotic disorders are introduced in the section on schizophrenia and are not presented again in

the subsequent description of other psychotic disorders. This reaffirms

schizophrenia as the paradigmatic disorder associated with hallucinations, delusions, disorganization of speech, disorganized behavior, and

negative symptoms. The structure of the DSM-IV chapter creates the impression that the domains of psychosis are defined by schizophrenia

and that all patients presenting with the signs and symptoms of psychosis should be evaluated first for schizophrenia. However, the proper

diagnosis of a psychotic person includes a detailed exploration of all

domains of psychopathology as part of a comprehensive mental status

examination and with a review of the lifetime presentation of psychotic

features.

The DSM-5 chapter begins with a review of the domains of psychopathology that have historically been used for the categorical assessment of schizophrenia spectrum disorders. There are five such

domains: hallucinations, delusions, disorganized thought (speech),

disorganized or abnormal motor behavior (including catatonia), and

negative symptoms. We have made subtle changes to nomenclature

and concepts. One such change is the definition of delusions as

“fixed beliefs that are not amenable to change in light of conflicting

evidence,” not as “erroneous beliefs” (DSM-IV-TR) since it is often difficult, if not impossible, to establish the non-veridical nature of a belief (Spitzer, 1990; Coltheart et al., 2011). We hold on to the concept

of a bizarre delusion, but not to a special status of such delusions in

the differential diagnosis of delusional disorder and schizophrenia

(Cermolacce et al., 2010) (for further details, see Tandon et al.,

under review). Another change is a greater focus on abnormal

motor behavior and catatonia within the domain of disorganized behavior (for further details, see Bustillo et al., under review). The different psychiatric and medical conditions associated with catatonia

can now be diagnosed when at least three of 12 signs and symptoms

of catatonia are present (Peralta et al., 2010).

Two negative symptoms have been highlighted as particularly

prominent: diminished emotional expression and avolition (Blanchard

and Cohen, 2006; Messinger et al., 2011; Kring et al., 2013). This reflects

emerging evidence that the symptoms previously grouped together as

negative symptoms are separable at the level of clinical description, laboratory assessment of behavior, and studies of neural circuitry (Foussias

and Remington, 2008; Strauss et al., 2011; Der-Avakian and Markou,

2012).

3. Gradients of psychosis

The signs and symptoms of psychosis are on a continuum with

normal mental states (Allardyce et al., 2007). While some presentations are unequivocally beyond the most liberal spectrum of mental

health, many presentations are subtle and the demarcation of the

psychotic from the normal mental state is difficult. Assessment for

the presence of psychosis should consider whether beliefs are flexible; whether perceptions are linked to an external stimulus; whether

thoughts are logical, coherent, and goal directed; whether the individual engages readily in normal verbal communication and motor

acts; and whether affect is modulated and of full range. If any of

these assessments raise concern, further evaluation for a psychotic

disorder is warranted.

The severity of a psychotic disorder can be defined by the level, number, and duration of psychotic signs and symptoms. The diagnosis of

more severe psychotic disorders should only be made after time limited

or less severe conditions have been excluded. This process demands patience, since final clarification often takes months, sometimes years. It

also requires a thoughtful search for etiological factors that can explain

the condition and, at times, may provide the opportunity for treatment

and prevention (e.g., drug use and medical illnesses).

The schizophrenia spectrum chapter guides the diagnostician

along the severity gradients of level, number, and duration of symptoms. The best estimate diagnosis is the one that includes all of the

clinical features at the time of the interview, taking into consideration

any medical condition that may explain the psychosis and a review of

the lifetime prevalence of psychotic and mood symptoms. This remains a considerable challenge, but the reliability of the revised

criteria for schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder included in

the DSM-5 proved to be acceptable (Regier et al., 2012).

Schizotypal personality disorder is recognized in the chapter as

below the threshold required for the diagnosis of a psychotic disorder,

whereas the attenuated psychosis syndrome is presented in section III

of the DSM-5, requiring further studies before being considered for a

new diagnostic category in the main text. Schizotypal personality disorder is part of the schizophrenia spectrum (Siever and Davis, 2004), but

the abnormalities of perceptual experience, belief, and affect are below

the threshold for the diagnosis of any psychotic disorder. The attenuated psychosis syndrome refers to the presence of psychotic symptoms in

attenuated forms (e.g., delusional ideas, perceptual abnormalities, disorganized speech) that occur with relatively intact reality testing, but

with sufficient severity and/or frequency to warrant clinical attention

(Tandon and Carpenter, 2012) (for further details, see Tsuang et al.,

under review).

Two conditions are defined by abnormalities limited to just one

domain of psychosis: delusional disorder and catatonia. In tandem

with the removal of bizarre delusion as a pathognomonic sign of

schizophrenia, bizarre delusions are no longer considered an exclusion criterion for the diagnosis of delusional disorder. While some

have argued that catatonia should be considered an independent diagnostic class (Fink and Taylor, 2008), we retained catatonia as one

of the five domains that define psychosis (Heckers et al., 2010). However, we removed catatonia as a subtype of schizophrenia, significantly

broadened the use of the catatonia specifier across the manual, and recognized catatonia as a diagnosis for cases where the medical and psychiatric etiology is unknown (for further details, see Bustillo et al.,

under review).

The chapter then defines two time-limited psychotic disorders: brief

psychotic disorder and schizophreniform disorder. Brief psychotic disorder lasts more than 1 day and remits by 1 month. The clinical features

of schizophreniform disorder are equivalent to schizophrenia, but the

duration is less than 6 months.

Two conditions are considered the most severe psychotic disorders

since they last for at least 1 month, involve multiple domains of psychopathology, and are not secondary to another condition: schizophrenia

Please cite this article as: Heckers, S., et al., Structure of the psychotic disorders classification in DSM 5, Schizophr. Res. (2013), http://dx.doi.org/

10.1016/j.schres.2013.04.039

S. Heckers et al. / Schizophrenia Research xxx (2013) xxx–xxx

3

and schizoaffective disorder (for further details, see Tandon et al., under

review; Malaspina et al., in press). They require the presence of two or

more of the five symptoms that define schizophrenia for at least one

month (criterion A). A crucial difference between schizophrenia and all

other psychotic disorders, including the closely related schizophreniform

and schizoaffective disorders, is a decrease in the level of functioning

below the level achieved prior to the onset of psychosis (criterion B for

schizophrenia).

The manual also defines disorders that are the direct consequence of

a primary condition that gives rise to psychotic symptoms: substance/

medication-induced psychotic disorder, psychotic disorder due to another medical condition, and catatonic disorder due to another medical

condition.

The chapter finishes with the diagnosis "Other specified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorder", for presentations

of psychosis that do not meet the criteria for any of the specific psychotic disorders defined in this section.

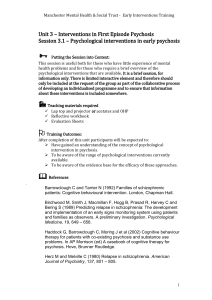

as well as cognition, depression, and mania (for further details, see

Barch et al., in press). Each dimension should be assessed on a fivepoint scale ranging from 0 (not present) to 4 (present and severe).

As an example, a score of 2 or higher on the scales that serve as diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia will be considered sufficient severity

to fulfill Criterion A. Fig. 1 depicts three different patients who have

been assessed with a rating of the eight dimensions. The graph easily

identifies the distinct features in the domain of psychosis and the related phenomena in the domains of cognition and affect.

This dimensional assessment is still very much grounded in the clinical description of schizophrenia spectrum disorders. We do not know

how these dimensions will map onto models of human behavior (e.g., decision making, reward behavior) or neural circuitry (e.g., thalamocortical

loops) (Gigerenzer and Gaissmaier, 2011; Bruno, 2011; Der-Avakian and

Markou, 2012). But this initial proposal to integrate dimensions into clinical practice can set the stage for a future alignment of psychiatric nosology and clinical neuroscience.

4. Dimensions of psychosis

5. Conclusion

Dimensional assessments capture meaningful variation in the severity of symptoms, which may help with treatment planning and

the prediction of course and outcome (Allardyce et al., 2007). It is

also the hope that dimensional approaches will accelerate the study

of disease mechanisms and ultimately the development of interventions to prevent and cure psychotic disorders (Heckers, 2008). In

the DSM-5, we propose that a patient who presents with the signs

and symptoms of psychosis should be assessed along eight dimensions: the five domains that define schizophrenia spectrum disorder

The discovery process in psychiatry is slow. Despite significant investments over the last 100 years, the mechanism of psychosis has

eluded us. While the emerging technologies of neuroscience and genetics have provided us with greater access to patients at the level of genes,

protein, cells, and circuits, these new data have been connected only

loosely to the well-known domains of psychopathology. It is likely

that the current nosology of psychotic disorders is not an adequate

template for the discovery of disease mechanisms (Heckers, 2008).

We have created a silent spring by disconnecting neuroscientific and

A

B

Abnormal Psychomotor

Behavior

Negative Symptom

Disorganized Speech

Impaired Cognition

Disorganized Speech

Depression

Hallucination

1

Hallucination

Abnormal Psychomotor

Behavior

Delusion

Mania

Abnormal Psychomotor

Behavior

Scores:1-4

Negative Symptom

Disorganized Speech

Hallucination

Mania

4

Scores:1-4

C

Depression

1

3

3

4

Impaired Cognition

2

2

Delusion

Negative Symptom

Impaired Cognition

Depression

1

2

3

Delusion

Mania

4

Scores:1-4

Fig. 1. Dimensional assessment of psychosis. The graphs depict three different patients who have been assessed for dimensions of psychosis (blue) and related phenomena in the

domains of cognition and affect (red). (A) A patient with schizophrenia displays moderate hallucinations, prominent delusions, equivocal disorganization of speech, but no abnormalities of psychomotor behavior or negative symptoms. In addition, the patient has mild cognitive impairment and equivocal mania and depression. (B) A patient with

schizoaffective disorder displays moderate hallucinations, prominent delusions, equivocal disorganization of speech, but no abnormalities of psychomotor behavior or negative

symptoms. In addition, the patient has mild cognitive impairment, severe depression, and mild mania. (C) A patient with deficit syndrome schizophrenia displays mild hallucinations, mild delusions, moderate disorganization of speech, no abnormalities of psychomotor behavior, and severe negative symptoms. In addition, the patient has severe cognitive

impairment, equivocal depression, but no mania.

Please cite this article as: Heckers, S., et al., Structure of the psychotic disorders classification in DSM 5, Schizophr. Res. (2013), http://dx.doi.org/

10.1016/j.schres.2013.04.039

4

S. Heckers et al. / Schizophrenia Research xxx (2013) xxx–xxx

genetic data from a rich literature in clinical psychiatry and psychopathology (Andreasen, 1998). The schizophrenia spectrum chapter emphasizes the dimensions of psychosis but still defines psychotic

disorder categories. It is our hope that future editions of the DSM can replace the current severity gradients (level, number, and duration) with

criteria that more accurately capture the mechanism of psychosis. This

requires translational research and the validation of new criteria sets

in clinical practice. It will be worth the effort since it will we get us closer to the prevention and cure of psychotic disorders.

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared all relevant conflicts of interest regarding their work on

the DSM-5 Psychotic Disorders work group to the APA on an annual basis. The complete details are posted on the public Web site http://www.dsm5.org/MeetUs/Pages/

PsychoticDisorders.aspx.

Acknowledgment

The authors do not have to declare any funding or administrative support for this

manuscript.

References

Allardyce, J., Gaebel, W., Zielasek, J., van Os, J., 2007. Deconstructing Psychosis Conference February 2006: the validity of schizophrenia and alternative approaches to

the classification of psychosis. Schizophr. Bull. 33 (4), 863–867.

Andreasen, N.C., 1998. Understanding schizophrenia: a silent spring? Am. J. Psychiatry

155, 1657–1659.

Barch, D.M., Bustillo, J., Gaebel, W., Gur, R.E., Heckers, S., Malaspina, D., Owen, M.J.,

Schultz, S., Tandon, R., Tsuang, M.T., Van Os, J., Carpenter, W., 2013. Logic and justification for dimensional assessment of symptoms and related clinical phenomena

in psychosis. Schizophr. Res. (this issue).

Blanchard, J.J., Cohen, A.S., 2006. The structure of negative symptoms within schizophrenia: implications for assessment. Schizophr. Bull. 32 (2), 238–245.

Bruno, R.M., 2011. Synchrony in sensation. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 21 (5), 701–708.

Bustillo, J., Heckers, S., Tandon, R., Barch, D.M., Gaebel, W., Gur, R.E., Malaspina, D.,

Owen, M.J., Schultz, S., Tsuang, M.T., Van Os, J., Carpenter, W., 2013. Catatonia in

DSM-5. Schizophr. Res. (this issue).

Cermolacce, M., Sass, L., Parnas, J., 2010. What is bizarre in bizarre delusions? A critical

review. Schizophr. Bull. 36 (4), 667–679.

Coltheart, M., Langdon, R., McKay, R., 2011. Delusional belief. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 62,

271–298.

Cuthbert, B.N., Insel, T.R., 2010. Toward new approaches to psychotic disorders: the

NIMH Research Domain Criteria project. Schizophr. Bull. 36 (6), 1061–1062.

Der-Avakian, A., Markou, A., 2012. The neurobiology of anhedonia and other rewardrelated deficits. Trends Neurosci. 35 (1), 68–77.

Fink, M., Taylor, M.A., 2008. Issues for DSM-V: the medical diagnostic model. Am. J. Psychiatry 165 (7), 799.

Fischer, B.A., Carpenter Jr., W.T., 2009. Will the Kraepelinian dichotomy survive DSMV? Neuropsychopharmacol. 34 (9), 2081–2087.

Foussias, G., Remington, G., 2010. Negative symptoms in schizophrenia: avolition and

Occam's razor. Schizophr. Bull. 36, 359–369.

Gigerenzer, G., Gaissmaier, W., 2011. Heuristic decision making. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 62,

451–482.

Heckers, S., 2008. Making progress in schizophrenia research. Schizophr. Bull. 34 (4),

591–594.

Heckers, S., 2011. Bleuler and the neurobiology of schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 37

(6), 1131–1135.

Heckers, S., Tandon, R., Bustillo, J., 2010. Catatonia in the DSM—shall we move or not?

Schizophr. Bull. 36 (2), 205–207.

Hyman, S.E., 2007. Can neuroscience be integrated into the DSM-V? Nature reviews.

Neuroscience 8 (9), 725–732.

Insel, T.R., 2010. Rethinking schizophrenia. Nature 468 (7321), 187–193.

Kring, A.M., Gur, R.E., Blanchard, J.J., Horan, W.P., Reise, S.P., 2013. The Clinical Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms (CAINS): final development and validation. Am. J. Psychiatry 170 (2), 165–172.

Kupfer, D.J., Regier, D.A., 2011. Neuroscience, clinical evidence, and the future of psychiatric classification in DSM-5. Am. J. Psychiatry 168 (7), 672–674.

Lieberman, J.A., First, M.B., 2007. Renaming schizophrenia. Bmj 334 (7585), 108.

Malaspina, D., Owen, M.J., Heckers, S., Tandon, R., Bustillo, J., Schultz, S., Barch, D.M.,

Gaebel, W., Gur, R.E., Tsuang, M.T., Van Os, J., Carpenter, W., 2013. Schizoaffective

disorder in the DSM-5. Schizophr. Res. (this issue).

Messinger, J.W., Tremeau, F., Antonius, D., Mendelsohn, E., Prudent, V., Stanford, A.D.,

Malaspina, D., 2011. Avolition and expressive deficits capture negative symptom

phenomenology: implications for DSM-5 and schizophrenia research. Clin.

Psychol. Rev. 31 (1), 161–168.

Peralta, V., Campos, M.S., de Jalon, E.G., Cuesta, M.J., 2010. DSM-IV catatonia signs and

criteria in first-episode, drug-naive, psychotic patients: psychometric validity and

response to antipsychotic medication. Schizophr. Res. 118 (1–3), 168–175.

Regier, D.A., Narrow, W.E., Clarke, D.E., Kraemer, H.C., Kuramoto, S.J., Kuhl, E.A., Kupfer,

D.J., 2013. DSM-5 field trials in the United States and Canada. Part II: test–retest reliability of selected categorical diagnoses. Am. J. Psychiatry 170, 59–70.

Siever, L.J., Davis, K.L., 2004. The pathophysiology of schizophrenia disorders: perspectives from the spectrum. Am. J. Psychiatry 161, 398–413.

Spitzer, M., 1990. On defining delusions. Compr. Psychiatry 31 (5), 377–397.

Strauss, G.P., Frank, M.J., Waltz, J.A., Kasanova, Z., Herbener, E.S., Gold, J.M., 2011. Deficits in positive reinforcement learning and uncertainty-driven exploration are associated with distinct aspects of negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Biol.

Psychiatry 69 (5), 424–431.

Tandon, R., Carpenter Jr., W.T., 2012. DSM-5 status of psychotic disorders: 1 year

prepublication. Schizophr. Bull. 38 (3), 369–370.

Tandon, R., Gaebel, W., Barch, D., Bustillo, J., Gur, R., Heckers, S., Malaspina, D., Owen,

M.J., Schultz, S., Tsuang, M.T., Van Os, J., Carpenter, W., 2013. Definition and description of schizophrenia in the DSM-5. Schizophr. Res. (this issue).

Tsuang, M.T., Van Os, J., Tandon, R., Barch, D.M., Bustillo, J., Gaebel, W., Gur, R.E.,

Heckers, S., Malaspina, D., Owen, M.J., Schultz, S., Carpenter, W., 2013. Attentuated

psychosis syndrome in DSM-5. Schizophr. Res. (this issue).

Umehara, H., Fangerau, H., Gaebel, W., Kim, Y., Schott, H., Zielasek, J., 2011. From

“schizophrenia” to “disturbance of the integrity of the self”: causes and consequences of renaming schizophrenia in Japan in 2002. Nervenarzt 82 (9),

1160–1168.

Please cite this article as: Heckers, S., et al., Structure of the psychotic disorders classification in DSM 5, Schizophr. Res. (2013), http://dx.doi.org/

10.1016/j.schres.2013.04.039