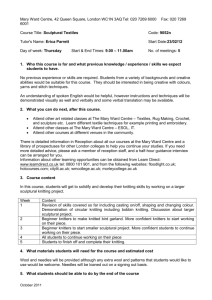

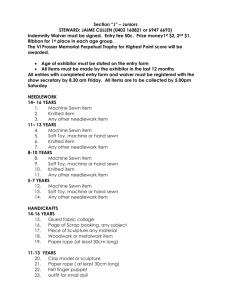

Women and Needlework in Britain, 1920-1970

advertisement