SiSU: - Open Price Terms in the CISG, the UCC and Mexican

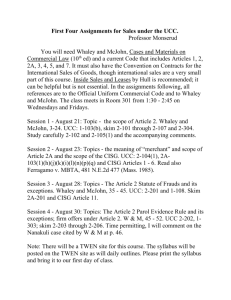

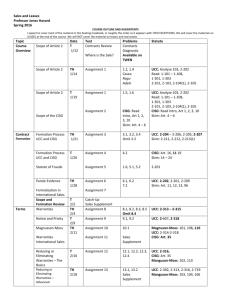

advertisement