Communication Text 4th ed.

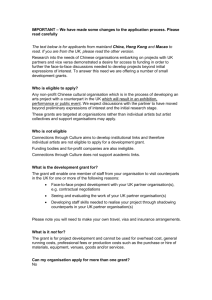

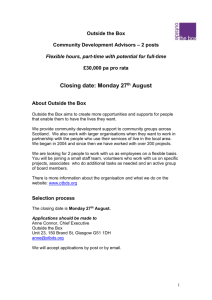

advertisement